In the first half of the 1890s, the country was burning in the fever of the millennium. It was primarily public institutions that worked hard to celebrate the thousandth anniversary of the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin with dignity, but private capital also felt the opportunity and began to invest. As the central program of the series of events, the large-scale exhibition, was held in Városliget, its surroundings were especially promising, so on the northern edge of the Liget, dr. Iván Bossányi, a Budapest lawyer and a partner of some entrepreneurs, built an entire entertainment centre called Ős-Budavára.

For this purpose, the Ős-Budavára Limited Liability Company was established on 17 October 1895, and construction began in the area leased from the Zoo. On the 70,000 square meters, a quarter showing the Turkish-era state of Buda Castle was established, which was intended to be temporary, so it was made of wood and plaster, but its facades were shaped quite faithfully. The design was entrusted to Oskar Marmorek, who had already built a similar complex in Vienna. He contracted Emil Vidor to develop the detailed plans and to manage the construction, who later became a prominent figure in Hungarian Art Nouveau architecture (one of his works, the Bedő House, now houses the Hungarian Art Nouveau House).

The main entrance of Ős-Budavára (Source: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.09.112)

The layout of the quarter was based on an engraving from 1686 made by an Italian technical officer, Marsigli, when the castle was recaptured. The entrance was a copy of the Fehérvár gate and several old buildings were recognizable, including the old town hall in Buda. Szent György Square was also built, with the Music Pavilion in the middle, the top of which was decorated with an arabesque pattern and held on four corners by four slender columns. The weight of the roof was led by wavy, curtain-like brackets onto semicircular columns. Above the corners, the roof was crowned with onion helmets, and the strongly protruding main ledge even bore battlements.

Szent György Square, with the Music Pavilion in the middle (Source: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.09.138)

A mosque was also built in the main square of Ős-Budavár, in which real services were held, and a muezzin sang in the associated minaret on its main façade. The slender tower of the minaret was surrounded by three passageways, the lower one was still closed and loggia-like, the middle and upper ones were open, which were held from below by brackets. There were towers and smaller domes at the corners of the mosque, and a larger dome in the middle covered the building. Here, too, the façade was crowned by battlements, which is very frequent on Eastern buildings.

The Mosque on the main square (Source: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.09.132)

So Islamic architecture appeared to the brim in the entertainment centre. In fact, it is understandable that the oriental atmosphere has dominated so much, as the exotic environment has helped those who wanted to relax even more to break away from the ordinary, the fabulous East could have been an extraordinary attraction. On the other side of the city, on the section of the Buda Danube bank between the Petőfi and Rákóczi bridges, people were also lured into the entertainment district built in the 1890s. A copy of the Hagia Sophia was built in the area called Little Constantinople, and a series of bazaars and harems around the large lake in the middle offered entertainment.

Janicsár Square in Little Constantinople (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 6 September 1896)

At the same time as these fantastic businesses, a small building has been erected that still stands today and attracts attention with its oriental style: the Uránia National Film Theatre. The building that housed the famous institution was originally built as a place of amusement. The owner of the idea was Kálmán Rimanóczy, an architect from Nagyvárad [today Oradea], who designed the building that included the concert and dance hall in 1895-96 with the architect Henrik Schmahl on Rákóczi (then Kerepesi) Road.

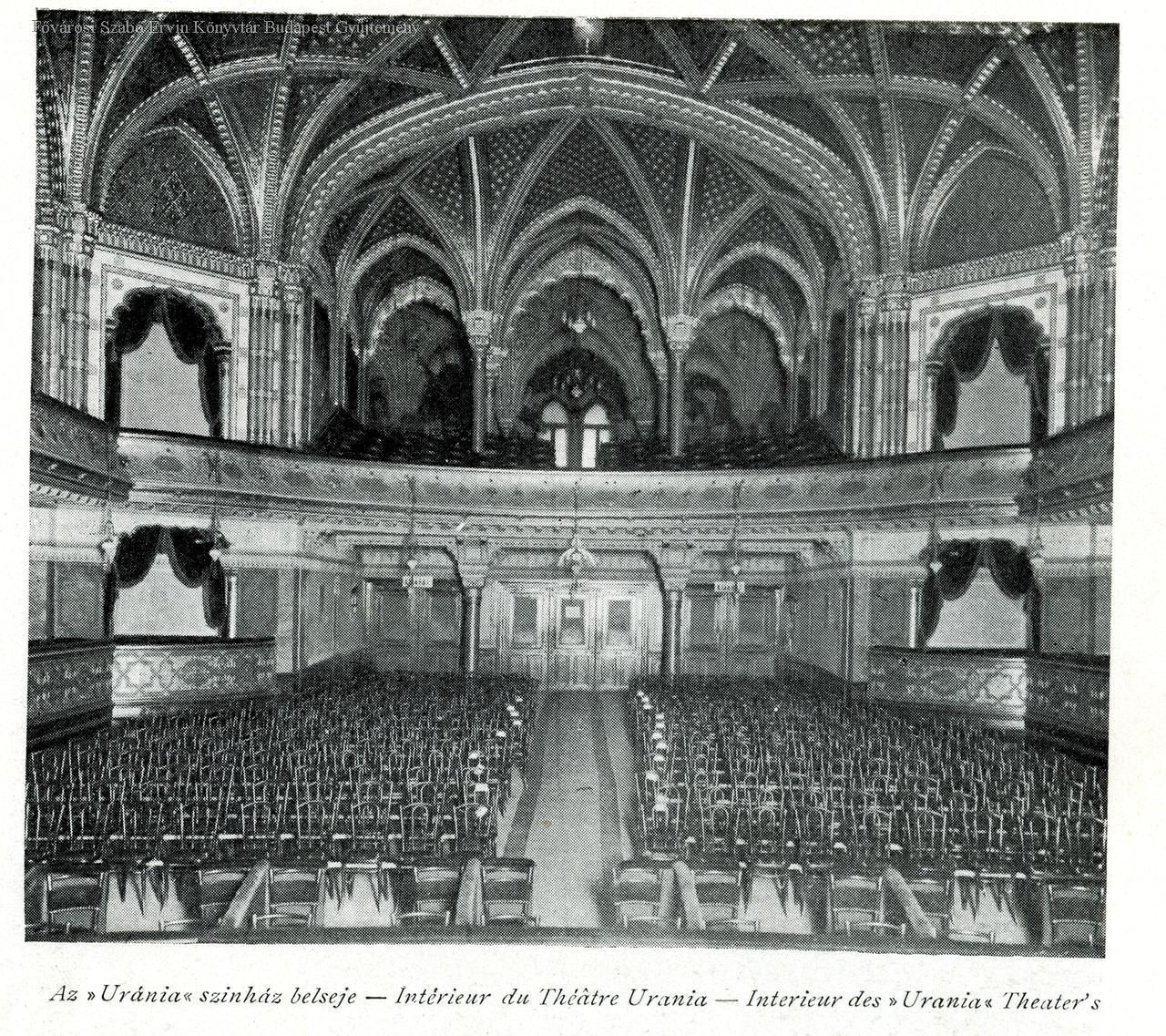

The auditorium is covered with a domed vault, and due to its high ceiling height, lodges have been built in it, from which the stage performance can be followed through horseshoe-shaped openings typical of Islamic architecture. Their red surface is covered with a gilded arabesque pattern, and the geometric decoration is dominant in the articles of the domed vault reinforced with ribs. The two basic colors are complemented by blue, green and brown patterns and they complete the colour splendour.

The auditorium of Urania around 1902 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The so-called Moorish style is also dominant on the main façade. Due to this, it was even more prominent in the closed installation order of Rákóczi Road. The five-storey building is defined by five window axes, so the main façade provides a regular and harmonious overall view. The individual levels are separated by accentuated cornices and even balconies at the height of the first and fourth floors, so the façade becomes horizontal despite the fact that it is very high and even decorated with a battlement.

The main façade of Urania has a horizontal emphasis (Photo: Balázs Both / pestbuda.hu)

The densely placed battlement with small elements also has an oriental influence, but the Moorish style is actually reflected in the shape and decoration of the windows. The wide openings of the first floor close in a basket arch that breaks at several points, and in them triple windows sit, pulling back from the façade. The latter was composed by the designer in such a way that the middle opening is both wider and higher than the sides, and its semicircular closure is broken at several points.

The imaginative first and second floor windows (Photo: Balázs Both / pestbuda.hu)

On the second floor we can see a similar window design, but the openings closing with a horseshoe arch no longer step back from the plane of the façade and they do not have a large, comprehensive frame. Yet this can be considered the main floor and not only because it is located in the middle, but also because there are reliefs lined between the triple windows. The works praising the talent of Sándor Krisztián depict Middle Eastern scenes: on one of them a pair of snake enchanters play the flute, on the other a couple listens to a singer, and on the others the figures of dancers fill the recessed fields.

.jpg)

We can see Middle Eastern scenes in the reliefs (Photo: Kristóf Kelecsényi)

But not only the figural ornaments but also the plant ornamentation is orientalizing: the surface of the cornices is covered with an arabesque pattern. In the twin windows of the third and fourth floors, the three openings are exactly the same size and their horseshoes rely on common so-called cube-headed half-columns. Their closer togetherness is also indicated by the façade architecture: they are connected by a straight eyebrow ledge at the bottom and a donkey-backed frame at the top. The stems and arches of the windows have a serrated edge even on the outermost, single-hole shaft, and their surface is decorated with a plant pattern.

Ornate twin windows open on the upper levels of the façade (Photo: Balázs Both / pestbuda.hu)

The construction was still in full swing, when in the autumn of 1895 Kálmán Rimanóczy managed to find a tenant in the person of the writer Antal Oroszi. The deal was good for both of them, as Oroszi's light pieces were hugely popular, but he always had to share the revenue with his former business associates. At that time Oroszi was finally able to open his own music hall called Caprice, for which, of course, he paid rent to Rimanóczy. As a businessman, however, he no longer proved to be as talented as he had already gone bankrupt in May 1898. Little Constantinople could not last much longer, and the entertainment district on the banks of the Danube was destroyed in 1899. But Ős-Budavár was also loss-making, so in 1907 it was closed.

So the entertaining places of amusement, with their exciting backdrops of oriental architecture, couldn’t entice people in the long run either. In any case, the method is an extremely interesting cultural monument, as evidenced by the special facade and interiors of Uránia to this day.

In the cover photo: The bazaar of Ős-Budavár (Source: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.09.125)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration