The flood of February 1876 was the second largest in the life of Pest-Buda (Budapest since 1873), and both cities along the Danube suffered significant damage. Fortunately, the flood did not claim human lives, but the financial loss was significant, and not in Pest, but rather in Buda because the finished river embankments protected the city on the left bank.

The flooding of the river hit not only the capital but also other towns and cities, for example, Esztergom, significantly. In addition, not only the Danube but also the Tisza flooded, which increased the damage nationwide.

The flood of 1876 in Buda, on Fazekas (today's Szilágyi Dezső) Square, photographed by Antal Lovich (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Within a few days after the Budapest peak, on 28 February, Prime Minister Kálmán Tisza and the Minister of the Interior made a call to the people of the country to help the flood victims. The call also appeared in the press, asking the citizens to make sacrifices. On 1 March, Budapest also encouraged its citizens to donate and work together.

Buda was hit harder by the flood of 1876, and Prime Minister Kálmán Tisza and the Minister of the Interior issued a call to the people of the country to help the victims (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The scale of the cooperation is well illustrated by the fact that many forms of assistance were implemented in response to the call. Money, crops, food and clothing, were collected among other things – everyone helped as best they could. There was widespread solidarity among the population, which moved all strata: from those at the top of society to the lower levels, both ecclesiastical and secular.

The palace of Count Alajos Károlyi on today's Pollack Mihály Square, which housed an applied art exhibition to help flood victims in 1876 (Photo: Zsolt Dubniczky/pestbuda.hu)

A charity event of some members of the Hungarian aristocracy fit into the framework of this assistance. In an exhibition of art history and applied arts, they wanted to present all the art treasures that were mostly privately owned and not yet visible to the general public.

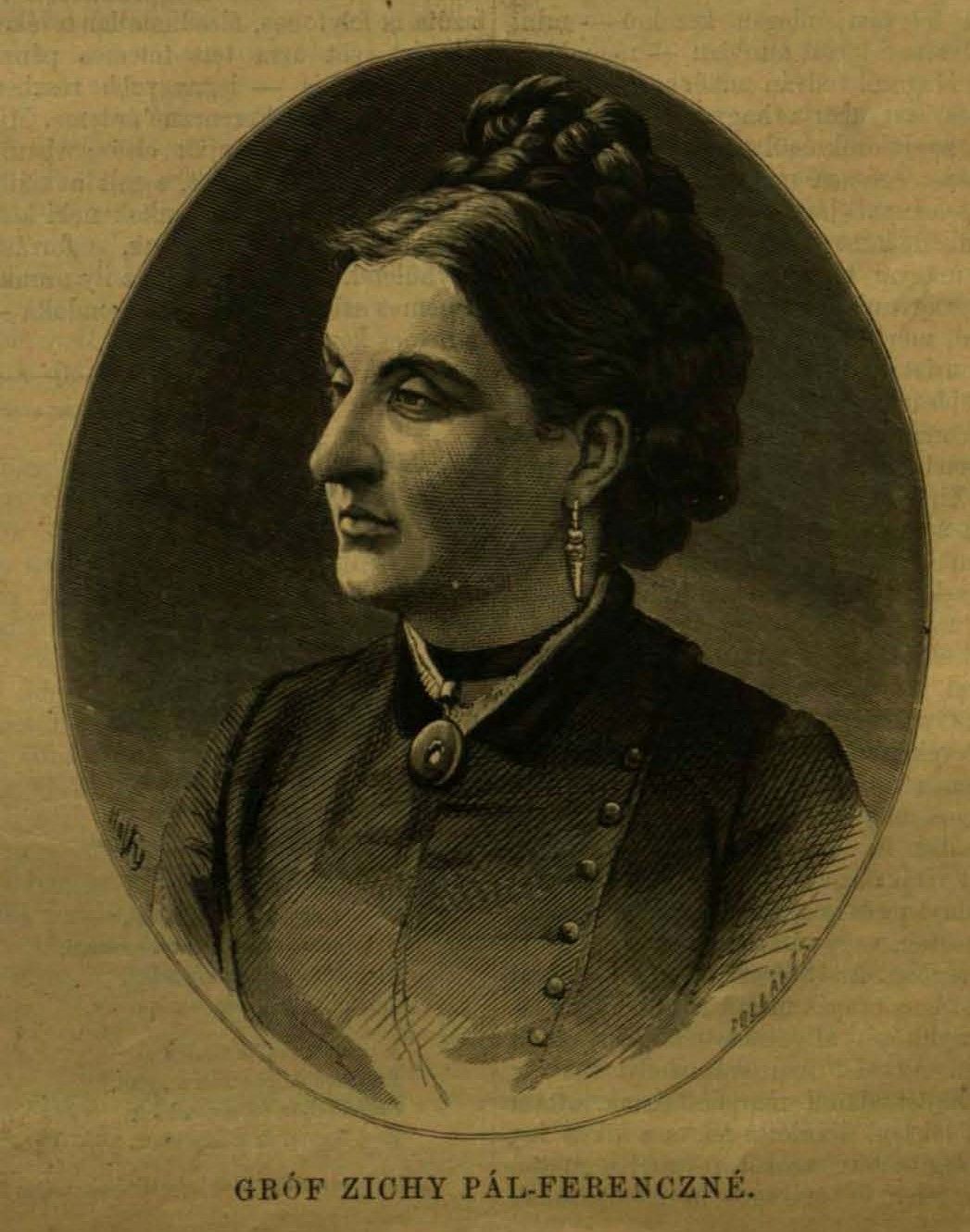

The idea of the exhibition can be linked to Count Mrs Pál Ferenc Zichy, who had already taken an active part in the charity events of the nobility. This time, not only was the idea her own, but she also undertook the arduous, meticulous work of organising and directing the 1876 exhibition.

Count Mrs Pál Ferenc Zichy, who organised the exhibition, had previously participated in several charity events (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 4 June 1876).

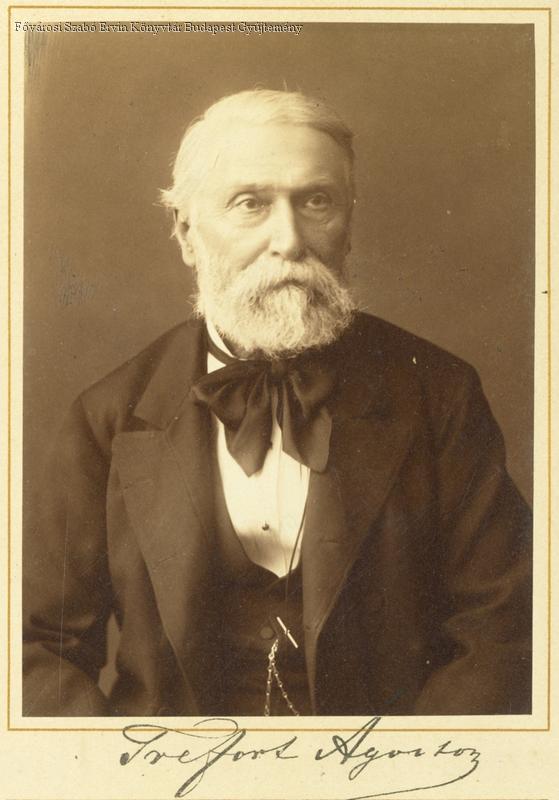

Organisational work began as early as March 1876. The exhibition was embraced at both governmental and social levels. Ágoston Trefort, the Minister of Religion and Public Education, became one of the main sponsors of the event, and aristocratic and church circles helped the noble initiative with their objects sent to the exhibition.

Ágoston Trefort, Minister of Religion and Public Education, one of the main sponsors of the exhibition to help flood victims, photographed by József Borsos (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

A committee was set up to organise the exhibition, chaired by Minister Trefort. Ferenc Pulszky, director of the Hungarian National Museum, Imre Henszlmann, archaeologist and art historian, on the ecclesiastical side, Flóris Rómer, archaeologist and art historian, guardian of the National Museum's antiquities archive, and Abbot Zsigmond Bubics, art historian, contributed as experts.

The organisers planned to open the exhibition on 1 May and originally intended to showcase the items in the Academy building. However, the large number of treasures received prompted the organisers to overwrite or redesign the original idea. Then it emerged that it would be worthwhile to organise the event behind the National Museum, in the Károlyi Palace on Pollack Mihály Square.

The building of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, where the exhibition was originally planned (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.028)

Of course, this meant a completely different function and role from the purpose of a private palace in the capital, which was made possible only by the fact that Count Alajos Károlyi, the builder and owner of the palace, did not use this building as a residence.

The house itself was built in 1871, but major decorative and interior design work may have been missing in 1876. Perhaps this also justified the fact that the walls of the reception rooms, which served as exhibition halls, were covered with draperies during the exhibition.

On the other hand, the capital did not yet have a significant number of large exhibition halls and public collection buildings and rooms during this period. And, of course, it should not be forgotten that the organiser, Countess Zichy, was in close contact with the Károlyi family, as her sister, Klára Kornis (Klarissza), was the wife of Ede Károlyi, who had a house built near the palace of Alajos Károlyi.

The final location of the exhibition: the palace of Count Alajos Károlyi on Pollack Mihály Square, photographed by György Klösz around 1880 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Significant help in organising the exhibition was that thanks to the offerings of various companies and corporations, the interiors of the palace could be transformed into elegant and aesthetic exhibition halls. The Viennese architect and decorative artist Leopold Bartelmus - an interior designer in the current sense - planned the interior decoration of the exhibition spaces.

The fabrics needed for the decoration were provided by the carpet and upholstery trading company of Fülöp Haas and Sons, whose imposing shop opened in 1874 on today's Vörösmarty Square. In addition, Gregersen Guilbrand, building joiner, István Forgó glazier, Vencel Pinsker upholsterer undertook all the works that served as the key to the successful organisation of the exhibition.

The inner courtyard of the Károlyi Palace covered with a glass roof, photographed by György Klösz around 1880. The interiors of the palace were transformed into elegant and aesthetic exhibition halls for the exhibition (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Logistics and the flow of information were much slower back then than they are today, so the items sent arrived late in April at the Academy building. Of course, at first, there was not even a specific deadline. Presumably, it was planned that when a significant amount of artworks arrived, the exhibition would be held, which finally opened its doors on 10 May. Presentable objects arrived at the exhibition even later.

The grand opening was attended by Queen Marie Henriette of Belgium, the youngest daughter of Archduke Joseph (Palatine of Hungary), and Prince Philip of Saxe-Coburg with his wife, Princess Louise. Numerous lords, politicians, ecclesiastical and secular people gathered for the occasion, many of whom were themselves exhibitors in the palace. The famous guests were guided in the halls by the organisers of the exhibition, but later they made a printed catalogue of the exhibited objects. This can be considered the first voluminous exhibition catalogue in Hungary - perhaps rather a registry at that time. Imre Henszlmann, Zsigmond Bubics and Imre Szalay took part in its compilation, and it was published not only in Hungarian but also in German.

Queen Marie Henriette of Belgium, the youngest daughter of Archduke Joseph (Palatine of Hungary), opened the exhibition. Painted by Franz Xavier Winterhalter in 1863.

Another significant event in the life of the exhibition was the visit of the reigning Franz Joseph on 21 May. He toured the halls accompanied by the organisers, looking at various objects, one or two of which he also made witty remarks.

According to coverage, the one and a half hours spent in the palace by Franz Joseph was not a ceremonial pastime but a real interest in objects from the field of mostly Hungarian applied arts. The visit was also warranted because the ruling couple had sent several objects related to Hungary from the Ambras collection of the royal court.

The main entrance of the Károlyi Palace on Pollack Mihály Square which only opens on ceremonial occasions (Source: Fortepan/No.: 93407)

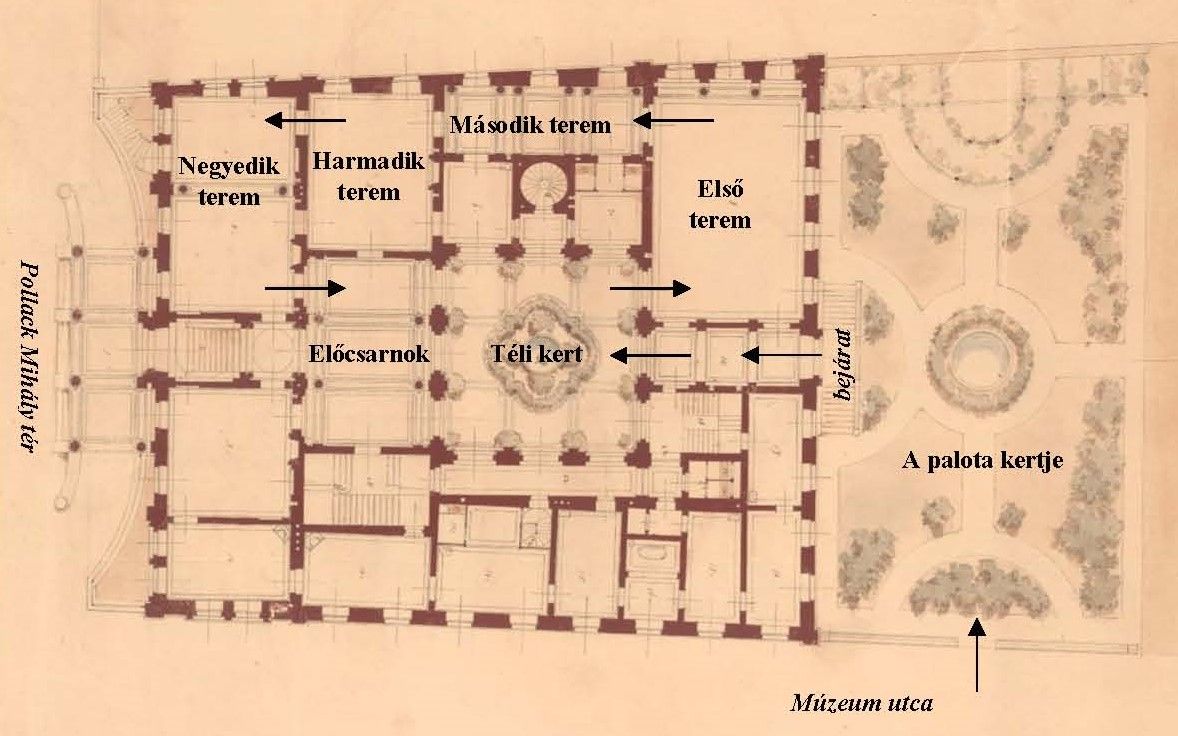

During ceremonial occasions, people would enter through the main entrance of the palace, but at other times access was possible through the garden behind the building. The entrance to the exhibition was also created there. The exhibition was held on the ground floor, where the larger halls and rooms on the north side were used for this purpose, along with the ornate atrium (conservatory) in the centre axis of the building.

Entrance to the back garden of the Károlyi Palace, photographed by György Klösz around 1875 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The Museum Street gate of the Károlyi Palace opens into the garden, photographed by György Klösz around 1880 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The location of the exhibition rooms allowed for a continuous route of travel within the building, which began at the palace's rear garden-facing entrance. Through the garden corridor opening from here – where the cash register operated – it was possible to get to the atrium in the middle of the building, where the visitor could admire the artefacts received from the ruling couple. From here, the route led to the first exhibition hall, which was arranged on the garden side of the palace, in the later dance hall.

Venues of the exhibition on the ground floor plan of the palace (Created by: Zsolt Dubniczky/pestbuda.hu)

This was followed by the longer and narrower second exhibition hall, the later mirror corridor, and the third and subsequent fourth hall, which later functioned as a salon and dining room within the building. From the fourth room, it was possible to get back to the atrium through the foyer and from there through the garden corridor to the garden.

The first exhibition hall, the later ballroom of the palace by Ignác Schrecker (Source: Museum of Applied Arts, No.: FLT 26371)

And what objects were exhibited? Everything that could be found in public and private collections of the time and depicted the centuries-old, lavish richness of Hungarian secular, ecclesiastical applied art. Flags, coins, paintings, weapons, books, diplomas and maps, clothes and accessories, bowls, goblets and cups.

The second hall of the exhibition, the later mirror corridor of the palace on a photograph by Ignác Schrecker (Source: Museum of Applied Arts, No.: FLT 26372)

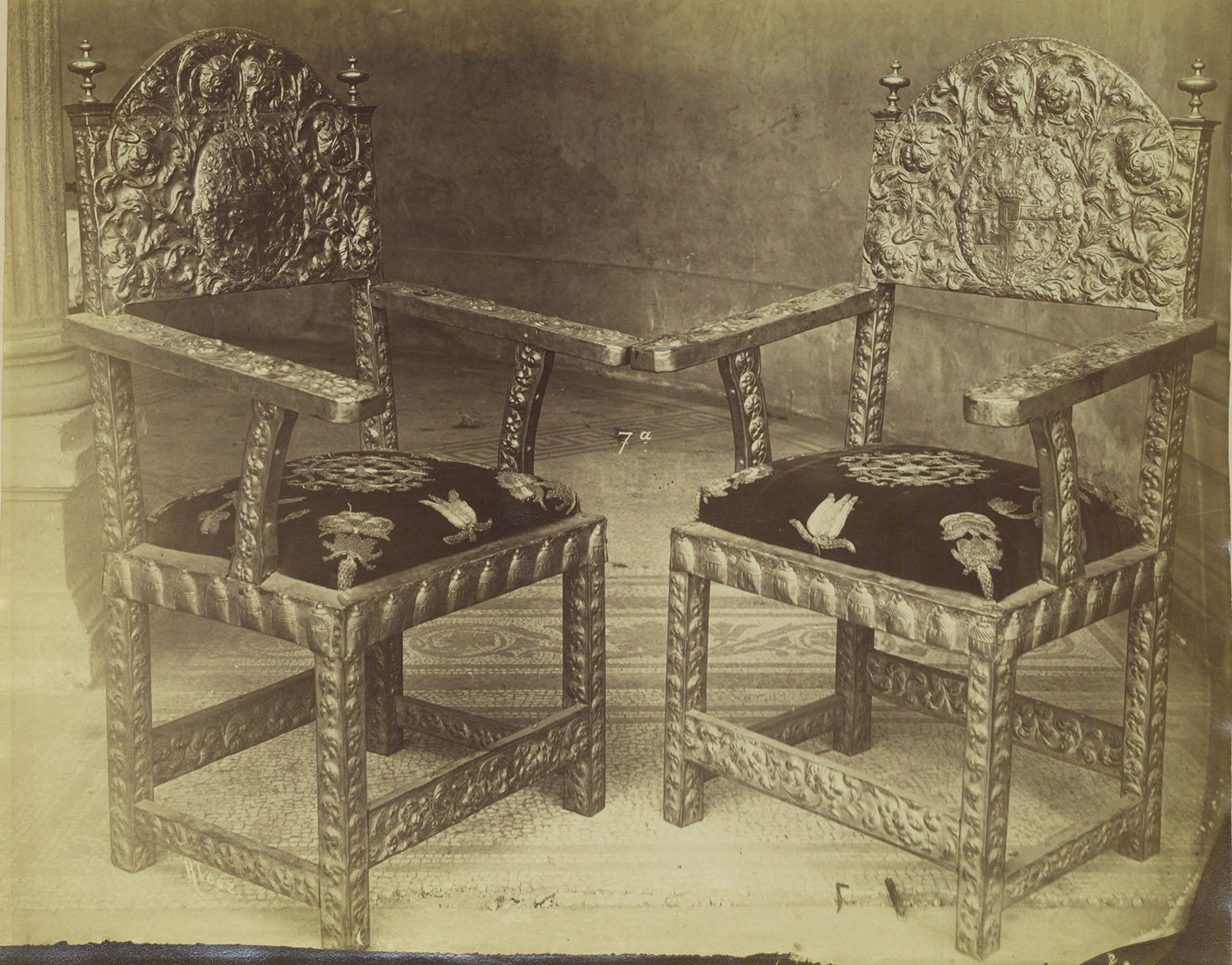

The placement of the objects was partly thematic, as shown by the fact that three of the four rooms were named after a major work of art or set of objects. This is how the first room was named Esterházy, because next to István Széchenyi, the "greatest Hungarian", the famous family was mostly commemorated here.

Armchairs decorated with silver plates from the Esterházy collection among the objects of the exhibition (Source: Budapest Archives, No.: HU_BFL_XV_19_d_1_03_002)

The third room and the most valuable part of the whole exhibition was a charcoal drawing by Leonardo da Vinci, owned by Miklós Esterházy, depicting St. Anne, Mary and the little Jesus playing with the lamb in her hands. Thus, this exhibition space was renamed the Leonardo Hall. The fourth room, which presented the treasures of ecclesiastical art, was called the Ecclesiastical Hall.

The fourth hall of the exhibition, presenting ecclesiastical treasures, the later dining room of the palace, photographed by Ignác Schrecker (Source: Museum of Applied Arts, No.: FLT 26374).

In the catalogue of the exhibition, 1201 numbered objects were listed, but in fact, there was much more than that, because on the one hand, those which arrived later were no longer included in this registry, and on the other hand, there were also those that were unnumbered.

The exhibition welcomed those interested for more than a month, until 15 June, and its income was 15,928 forints and 65 kreuzers.

Cover photo: The palace of Count Alajos Károlyi, the location of the exhibition in the photo of György Klösz, around 1880 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration