After the expulsion of the Turks, military structures were erected in Szent György Square in Buda Castle, and two artillery barracks stood on the Danube side, but they were used only until the end of the 18th century. Count Vince Sándor (1766–1823), imperial and royal chamberlain, bought them from the treasury in 1803 to build his own palace on their site. No credible evidence of the architect's identity has survived, but the plans were probably made by either Johann Aman of Vienna or Mihály Pollack. It is also conceivable that both of them worked on it: Aman, who was the head of the Vienna Royal Court of Architecture and a highly respected professional, was involved in the development of the basic concept, and Pollack was in charge of the construction, and he could also decorate the interior.

.jpg)

Mór Than: Portrait of Mihály Pollack (Source: Hungarian National Digital Archive)

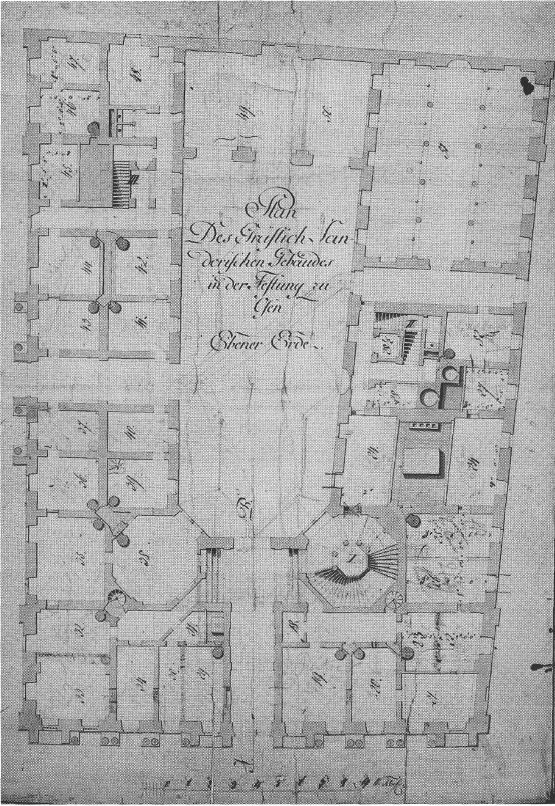

The barracks must have been in good condition, as they were not completely demolished, and their walls were used to build the palace. The building, with its irregular rectangular floor plan facing north-south, is organised around a central courtyard. The north (facing the Carmelite monastery) and the south (closer to the royal palace) wings were newly built, the two longer tracts enclosing the walls of the barracks. The main entrance opened in the middle of the south facade, which led through a long gateway to the courtyard. The entrances to the two side wings were similar in layout. The two levels of the building were connected by a circular main staircase at the inner end of the gateway, but there was also a staircase in the eastern and western wings. A second floor was built on the side facing the Danube, so the mass system of the building was not completely symmetrical.

Ground floor plan of Sándor Palace (Source: Hungarian Museum of Architecture)

This was not visible on the facades, it was characterised by perfect symmetry, which is characteristic of the classicist style that defined the first half of the 19th century. The building has a horizontal orientation, the ground floor and the first floor are separated by a belt course and close at the top with the main ledge. The upstairs windows have been given a sculptural arched moulding that encloses several openings in a specific order. Excessive monotony is protected by the airy vertical dividing elements: the wall sections (risalit) protruding a little at the two edges of the western facade are bounded by wide wall pillars (pilasters) which also cover the two levels of the building. The south-facing main facade is shorter, so there was no need for vertical articulation, only the risalit in the middle, the triangular tympanum crowning the top, and the pillars and columns lined up in front of the ground floor which supports the entire length of the facade.

The Sándor Palace seen from Szent György Street (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The basic idea of classicism was to recall ancient Greco-Roman culture, and accordingly, the columns represent the so-called Greek Doric column order, and the decoration of the belt course also fits into this. The most unique ornaments of the building, on the other hand, are the reliefs: one under the tympanum of the main facade, and two other long works can be seen connected to the belt course of the western facade. They praise the talent of the Bavarian sculptor Anton Kirchmayer and depict mythological and historical scenes: on the longer side is the Helicon Festival from the left, and the right is the triumphal procession of Venus. Dubbing Sándor a knight came to the forefront under the tympanum. The figures were depicted by the artist in a layout and Greek costume known from Greek art. These works of art carved out of grey stone stand out from the white-plastered facade, as do the garlands above the main entrance and on the side facade. The latter even have hidden masks that were common in Greek art. On the surface of the main facade tympanum, there is a year of handover with Roman numerals: MDCCCVI, i.e., 1806.

The main facade of the building (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

However, behind the modestly decorated facade, which radiates dignity, there is a completely different interior hidden. Already the vault of the gateway was densely decorated with cassettes with floral motifs, but the most impressive part was the first floor of the south wing: here an ornate row of halls was created, which originally reflected the power of the Counts of Sándor. According to a description from 1822, the palace was lined with colourful rooms: a white marble room (Mirror Room), a yellow upholstered bedroom, a reception room with green drapery, a red drapery lounge, a blue and yellow silk playroom, a grey drapery room, which is patterned like a Turkish tent, and a large hall with gilded carvings on the ceiling. Also for a representative purpose, a two-storey conservatory was built in the southern part of the wing facing the Danube, to the floor of which an exit from the count's living room opened.

Count Móric Sándor, the "devil of riders" (Source: wikipedia.org)

This richness of colour also indicated that Vince Sándor was not just any man. He came from a noble family - although only his father, Antal Sándor, received the title of count - nevertheless he often did not care about social expectations. For example, going to the theatre was not an upscale event according to him, he visited the Castle Theatre - the former Carmelite monastery - next to his palace every night, and connected the two buildings with a covered corridor so that he did not even have to step out into the street. The fact that he had set up a stable on the ground floor was not any strange, much more the equestrian stunts of his son, Móric. The count, who became famous as the "devil of riders", took over the management of his family after his father's death in 1823, and he did almost everything on horseback: this is how he travelled in his own house, and he often went to visit people like this too. Despite his unusual habits, he was popular in social life, which he upscaled by offering the half-yearly income of his estates to build the Chain Bridge.

The dubbing to knight of the Counts of Sándor in the relief under the tympanum (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

In 1831, Móric Sándor sold the palace to the Margrave Pallavicini Family, who had owned it for the next nearly half a century with longer or shorter interruptions. After the Revolution and the War of Independence, between 1851 and 1856, Archduke Albrecht established his residence here, and from 1867, following the Compromise, he leased it to the Office of the Prime Minister on the proposal of Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy. Later, Miklós Ybl, the most prestigious architect of the age, was commissioned to make a representative remodel of the interiors. It was finally taken over by the state in 1874 through an exchange transaction with the Pallavicini Family, during which the palace of 98 Sugárút (now Andrássy Avenue) was given to the margraves.

Terrace overlooking the Danube (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Ybl worked on the building in the 1870s and 1880s as well: in 1875, at the request of Prime Minister Kálmán Tisza, a so-called Tapestry Room (with blue walls) and a room named after Maria Theresa (with red walls) were built according to his plans. A decade later, the side facing the Danube became a work area, as the conservatory was demolished to replace it with a terrace on cast-iron columns. Reconstructions took place between the two world wars too: in 1927–28, the idea of Rezső Hikisch was realised, and the two neighbours of the Mirror Hall, the corner hall of the Council of Ministers and the ministerial waiting room were converted into a Neo-Empire style, and beautiful inlaid parquet was put in the so-called Round Salon. All that has changed on the facade is that on the north wing a relief of St. George was placed, made by Zsigmond Kisfaludi Strobl.

Inlaid parquet of the Round Salon (Source: Office of the President of the Republic)

World War II did not spare this building either, it suffered terrible damage during the siege: the southwestern part collapsed completely and the first floor of the main facade also collapsed. After that, only preservative restorations were carried out, and the second floor of the Danube-facing wing, which caused asymmetry, and the terrace overlooking the river were also demolished. During socialism, the stabilised building, like the royal palace, would have been used for cultural purposes, first by the Museum of Modern History and then by the Hungarian Museum of Architecture, but none of it took place, it was merely a museum warehouse. The facades were only reconstructed in the second half of the 1980s, which was also facilitated by the release of plans from the Pallavicini Family archives in 1983 showing the 1817 condition of the building.

The Mirror Hall is the venue for ceremonial events (Source: Office of the President of the Republic)

The complete restoration, including the interior, was planned by Ferenc Potzner in the autumn of 2000 and completed in the spring of 2002, 20 years ago. In doing so, the colourful representative rooms from the 19th century were restored, and the furniture was re-manufactured in the Neo-Empire style dominating between the two world wars. The snow-white Round Salon, the Blue Reception Salon, the Red Salon, the Rococo Mirror Hall and several smaller but tastefully furnished buildings have been used by the Office of the President of the Republic since 2003, giving the building a central role in the 21st century.

Cover photo: The main facade of the Sándor Palace (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration