After World War I, many people moved from overcrowded Budapest to the surrounding settlements, including Pesthidegkút, the newly parcelled part of which was called Remetekertváros. Among the Catholic faithful, there was soon a demand for a mass place there, so in 1929 an elderly couple offered their own house for a chapel. Their daughter, Margit Slachta, was also characterised by a deep faith in God and also an extraordinary desire to do something: a few years earlier, she founded a new religious order called the Sisters of Social Service. She put everything she had into the service of the downtrodden, and even entered politics in their interests, in 1920 she became the country's first female parliamentarian.

Margit Slachta, founder of the Sisters of Social Service (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

In Remetekertváros, she was not satisfied with half-solutions either, and in 1933 she managed to convince Pál Bozsik to undertake the task of organising the parish there. Bozsik was similarly temperamental and planned to build a new church, even though the parish was not officially established until the following year. The idea was also supported by the Sisters of Social Service, Margit Slachta only asked that it be dedicated to the Holy Spirit after its completion. Bozsik started a national collection to raise the funds, and with good business sense, he also started selling the graves of the future crypt quite early.

Thanks to the enthusiastic supporters, they were able to raise such a sum in a few years that they had to deal with the procurement of the plans as well. Bozsik asked Jenő Lechner for this, whom he had met in his previous parish, Gyöngyös. The architect undertook to prepare the plans completely free of charge, which he presented to the parish in the summer of 1937. Lechner was a talented architect as well as a sensitive artist who was always one of the first to follow the latest style trends. This was also the case with modernism, which began in the early thirties, the principles of which he applied as early as 1931 in an apartment building. Being the nephew of Ödön Lechner, he was also particularly interested in the issue of national style, which he could imagine in several forms, and which he even believed to be compatible with international modernism.

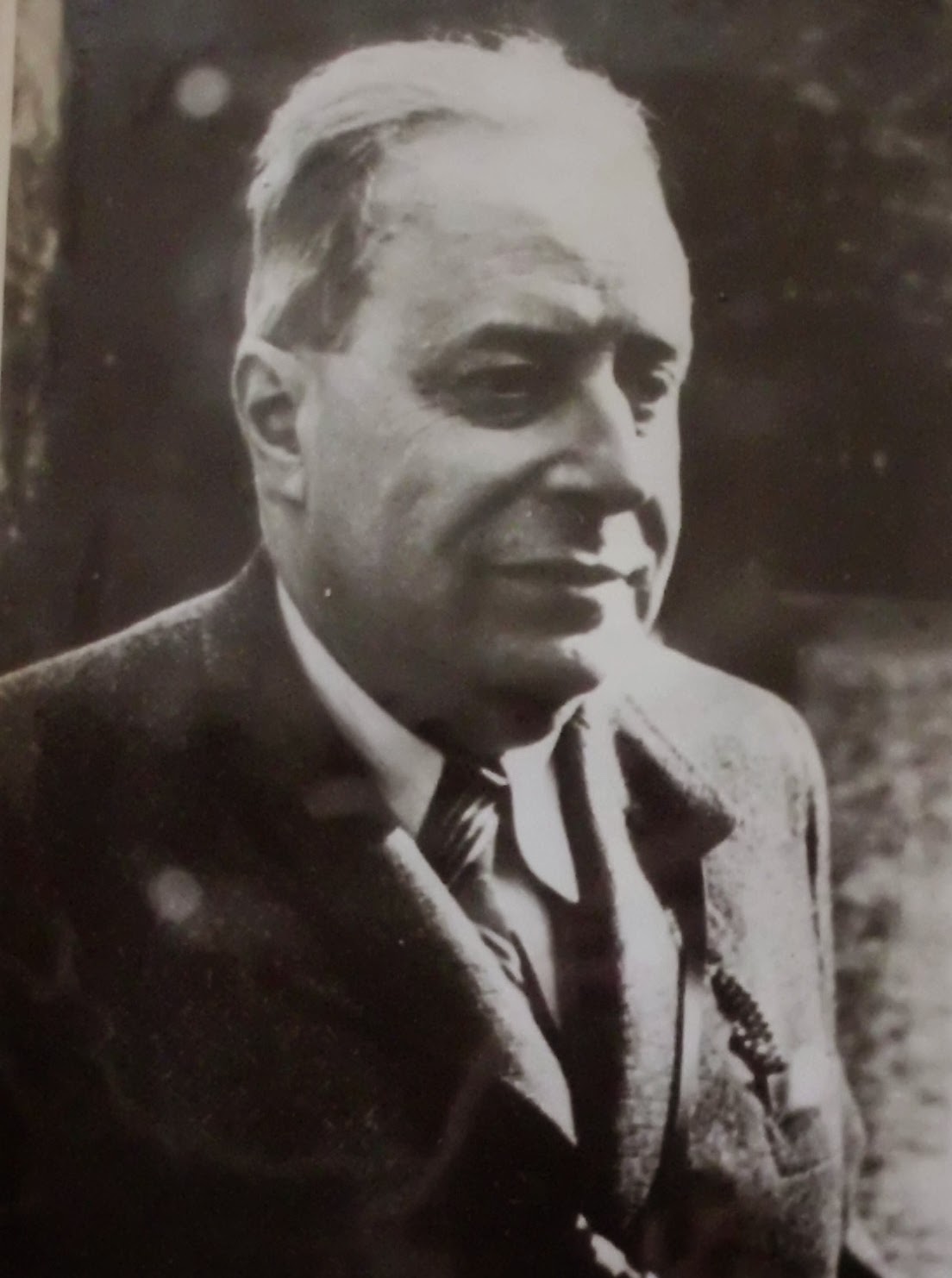

Jenő Lechner, the designer of the church (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

Lechner carried out serious architectural historical research, from which he deduced that nations with different temperaments always tried to mould individual styles to their own sense of beauty. This was the case, for example, with the Gothic and the Renaissance, which had Italian, German, French, and English versions. He was therefore convinced that sooner or later even the puritanical, functionalist modernism would acquire a national colour. He wanted to play his part in the creation of the Hungarian modern style, which he helped to do by mixing motifs referring to the eastern roots of Hungarian people into elementary geometric shapes.

In the first half of the 20th century, a significant part of the Hungarian art world was preoccupied with the idea of Turanism, according to which Hungarians originate from ancient Turan. It was envisioned as a vast empire in Inner Asia, from which the Chinese, Indians, Persians, and indeed all Asian nations had their roots. This idea became especially strong after Trianon, as surrounded by enemy countries, it filled people's hearts with a pleasant feeling that, even if far away, we still have relatives. Lechner tried to express this kinship by adopting the gate cult characteristic of ancient Persian architecture, which can also be observed in the church in Remetekertváros.

Main facade and entrances of the church at 34 Máriaremetei Road (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The main facade of the building is divided by three huge, pointed niches, at the bottom of which human-sized entrances open, but the niches themselves give the impression of giant gates. In them, light flows through narrow but very high windows into the interior, which is divided into three naves. In fact, the two side naves only serve as traffic corridors, but they also have a very aesthetic appearance: the designer carved the same pointed apex arches into the reinforced concrete pillars lined up here, as can be seen on the main facade. In addition, the floor plan of the pillars has the same shape, with their pointed edges facing the main nave. The spiritual centre of the interior, the sanctuary, is also expanded by an arched niche, known as an apse.

The interior of the church (Source: Remetekertváros Parish Church of The Holy Spirit website)

However, these characteristic forms are encompassed by a modern architectural framework. Its floor plan is a simple, elongated rectangle, and chapels are joined to the longer sides of which. Its structure is also characterised by angularity, it consists of elementary geometric shapes, which, however, have significant differences in height: the side chapels are dwarfed compared to the church building extended upwards. The crypt also contributes to the vertical emphasis of the building, but the steep roof really creates the feeling of height, which is in harmony with the arched niches of the main facade. On the east side of the sanctuary, a column-shaped tower is connected to the church, which perfectly reflects the aesthetics of modernism with its flat roof, although there were also plans to add a spire to it. In any case, the strip-like bell windows, which the designer placed under each other like the teeth of a comb, fit better with this flat roof.

The modern-style Remetekertváros church (Source: Fortepan/No.: 210007)

The interior space, capable of accommodating one thousand five hundred people, is closed at the top by a single huge flat ceiling, covered with ash wood, which runs forty metres long, without interruption, through the entire building, from the choir to the sanctuary. Its surface is decorated with wooden plates placed on their edges, imitating a ribbed mesh vault. This solution is very beneficial from the point of view of acoustics, and it also fits the arched forms, as it comes from the Gothic period. This style is also fortunate in the case of a temple because it can be associated with the church, which reached its true heyday in the Middle Ages.

The wooden ceiling covering the nave (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The vertical emphasis of the church is also valid in the interior, the sanctuary rises unusually high compared to the floor level of the main nave, and the already mentioned huge niche also fits into this concept. Modern architecture is also present in terms of the use of materials: reinforced concrete provides its structure. In fact, even the altar itself is made of this, but it was covered with green Italian marble, the so-called verde issoire. The building got the name emerald church from this opulent colour. The gilded letters from which the prayer to the patron saint was laid out are beautifully displayed on the green background: „Jöjj el Szentlélek Isten!” ["Come, Holy Spirit, God!"] The pulpit on the left side of the sanctuary is covered with the same marble, and even the pillars would have been originally covered with it. However, due to a lack of money, it was not realised, so the rough concrete surface of the pillars can still be seen today, which creates a very expressive effect.

The pulpit covered with green marble (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The lack of financial support was largely caused by the fact that the sale of the crypt graves progressed more slowly than expected, but the wartime conditions also contributed greatly. Although the ceremonial laying of the foundation stone took place in peacetime, in December 1937, most of the construction was during World War II. The crypt hidden in the ground was completed in 1938, but the construction of the ascending walls did not start until August of the following year. The weather was not favourable to the work either, because in November 1939 a huge storm knocked down the walls, which were already at full height. However, the cooperation of the faithful saved the matter, the church was put under the roof, and the tower was also built in 1942. Its ceremonial consecration was held on 29 June 1942, but at that time it was still quite bare inside and out. The coloured glass windows of the side naves - which depicted the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit and their function in the Church - were of course already in place.

The side naves are also decorated with coloured glass windows (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

However, it did not yet have benches, it was installed in the main nave only in 1943, following the plans of Jenő Lechner. The statues of St. Stephen and St. Ladislaus greet the faithful from the main facade since 1944, and the altarpieces of the side chapels were painted only in the 1940s and 1950s by excellent artists such as Masa Feszty or Pál Molnár-C.. Originally, Béla Kontuly would have painted a fresco in the sanctuary, but it was not realised because of the war, Géza Pogány's work depicting the coming of the Holy Spirit has only been visible here since 1982. The twelve statues of the saints placed on the pillars were carved by Zoltán Vida at the very end of the 20th century, between 1995 and 2000, which gave the church its current state.

Sixty-three years passed between the laying of the foundation stone and the placement of the last statue, but the church is still uniform since the furnishings were implemented according to Jenő Lechner's original plans. Although many people criticised the architect's fantastic but very expensive ideas in his time, fortunately, the faithful stuck to him and are still proud of this great gemstone, the emerald church.

Cover photo: The Remetekertváros church in 1961 (Source: Fortepan/No.: 210007)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration