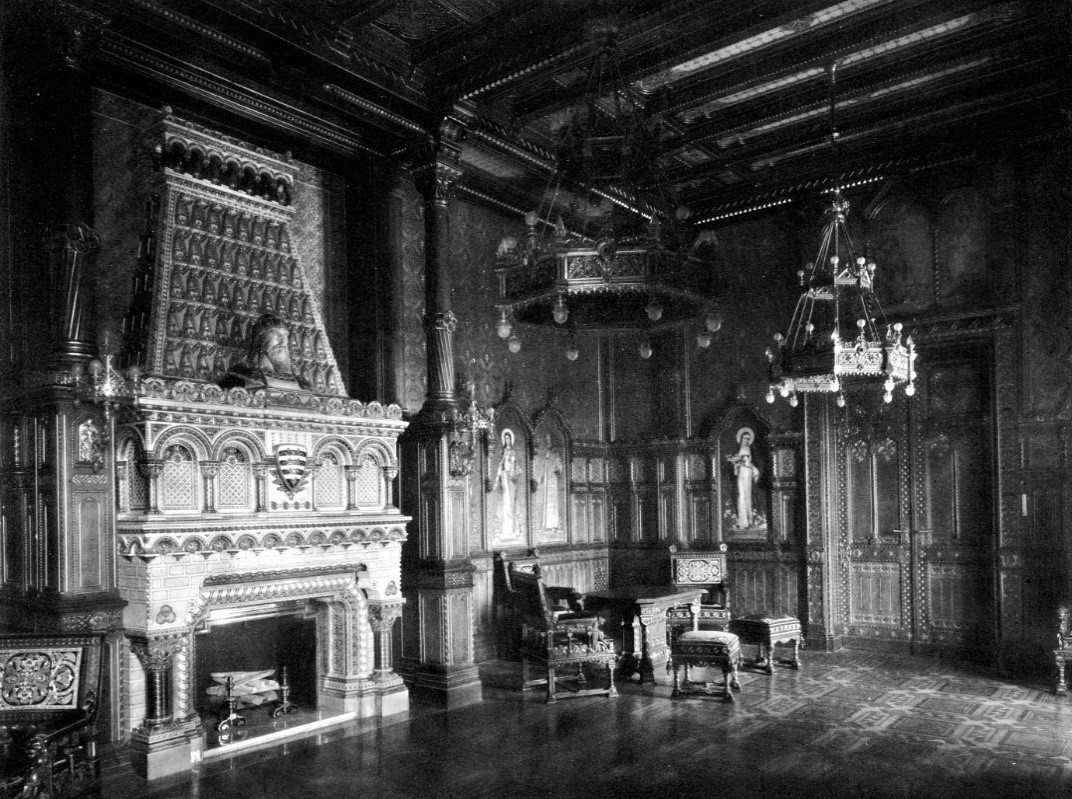

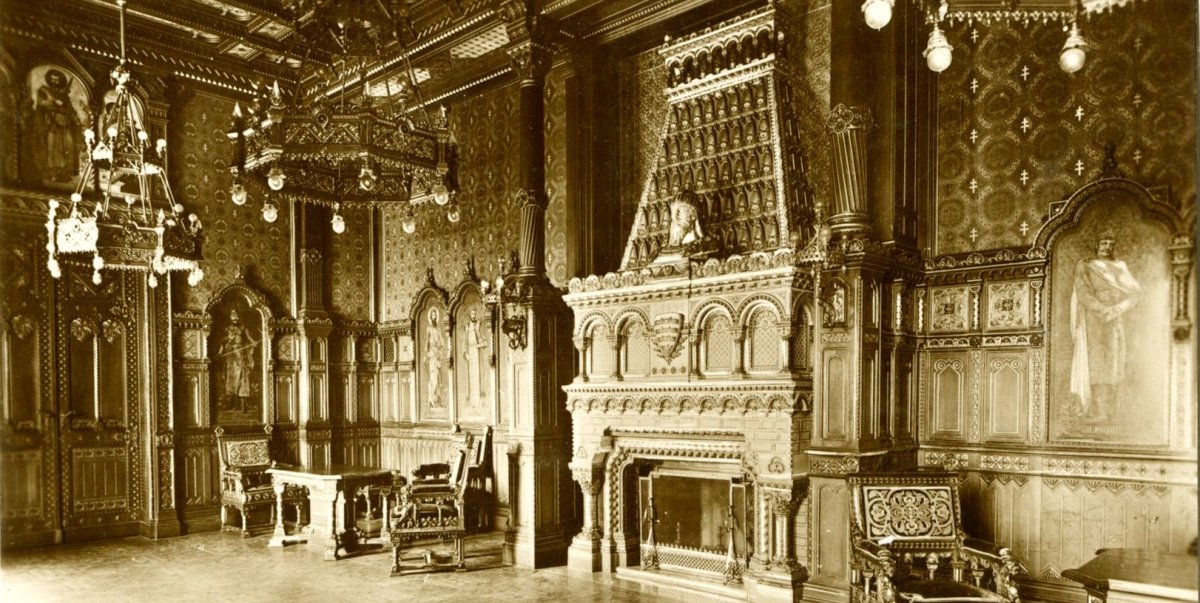

When the St. Stephen's Hall and the Zsolnay Fireplace were made at the turn of the century, it caused just as much attention as it does today, at the time of its restoration. "It has a mystical and dazzling effect on man," the journalist of Budapesti Hírlap explained in 1902 why he considered St. Stephen's Hall to be the most interesting and special room of the new royal palace. The correspondent, who, courtesy of Alajos Hauszmann, was able to take part in the first lighting test of the new royal palace, which was yet to be handed over, called the huge fireplace a stylized earthenware oven “made entirely of majolica”.

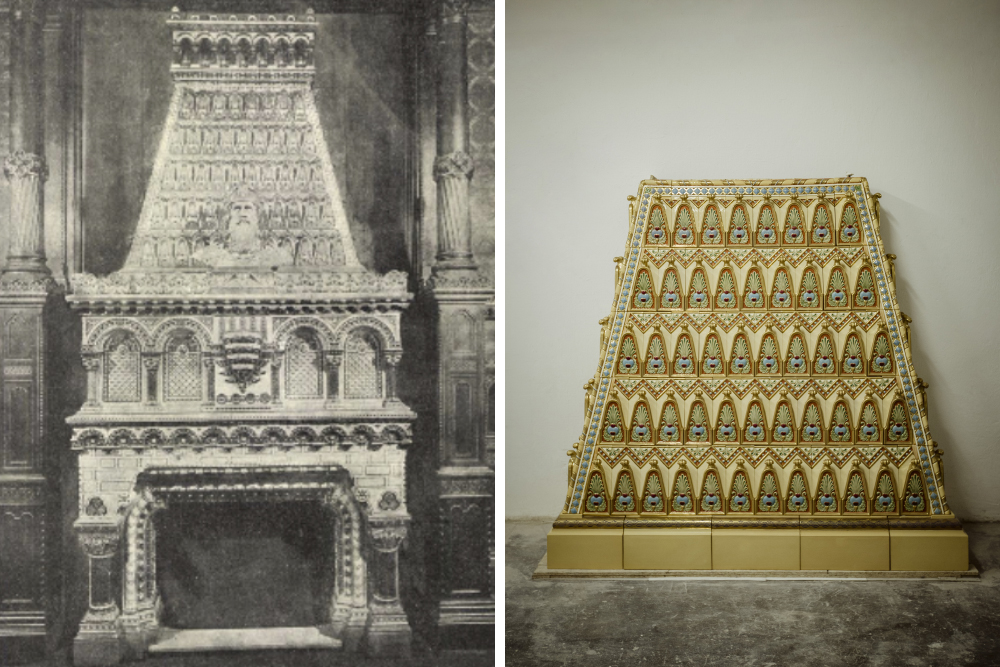

The fireplace of St. Stephen's Hall was assembled in 1900, before the World's Fair in Paris, in the workshop of Endre Thék on Üllői Road (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

It may seem unbelievable at first hearing, but the re-creation of this “earthenware oven” in the 21st century posed a much more difficult task for professionals than the creation of the original masterpiece at the turn of the century. The expert of the restoration of the St. Stephen's Hall, art historian Péter Rostás, and the designer of the hall and the Zsolnay Fireplace, architect Tibor Angyal, told Pestbuda about the reason for this.

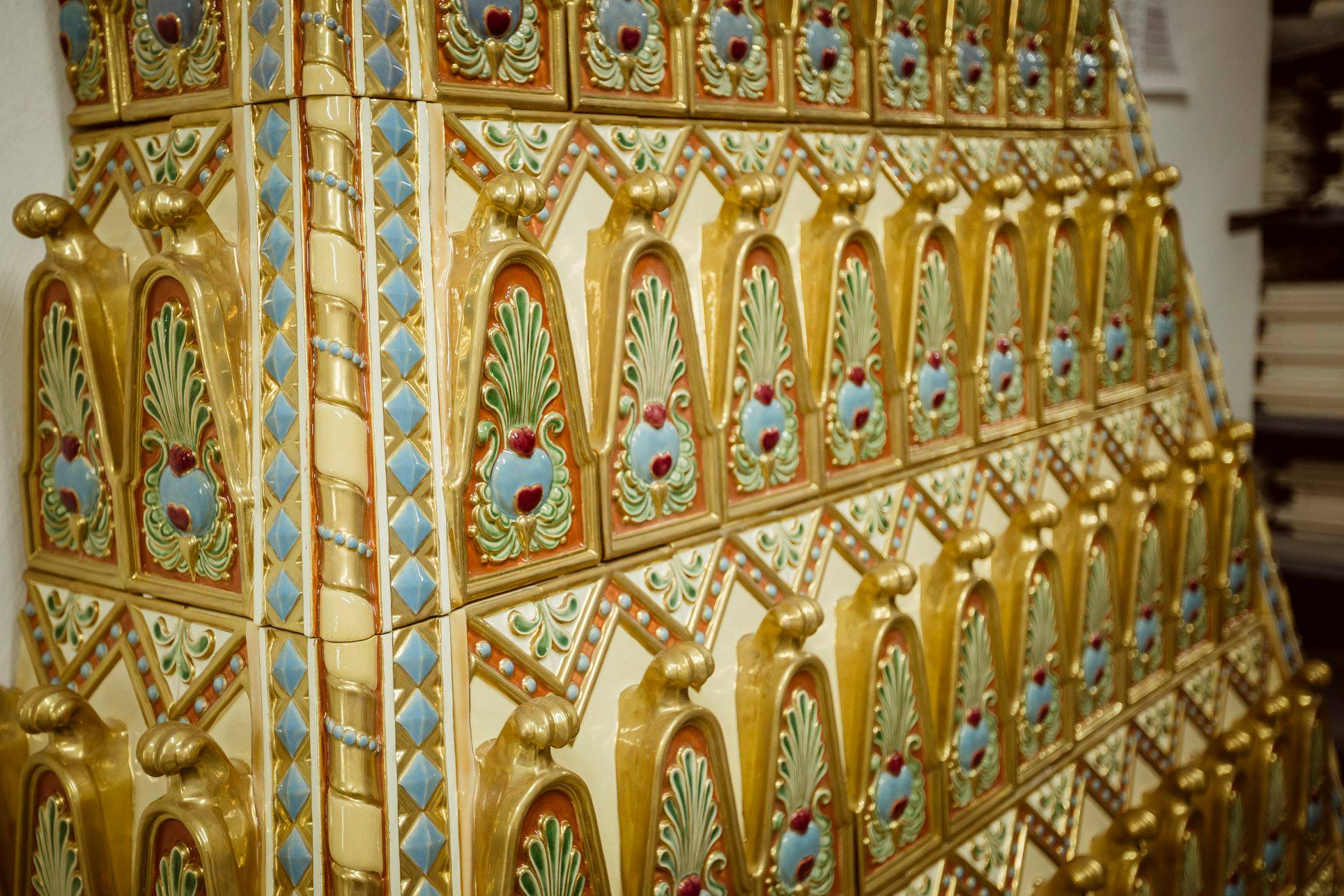

Chimney pipe of the recently re-created Zsolnay Fireplace in the Zsolnay Factory in Pécs, after the trial assembly (Photo: Várkapitányság)

The St. Stephen's Hall and the fireplace in it are both past and present today because the recall of the old glory relates to the experience of the re-creation taking place today. Unsurprisingly, the palace designed by Alajos Hauszmann also housed the masterpiece of the then already world-famous Pécs factory 120 years ago, as when the royal palace was rebuilt and tripled, it was a definite goal to display the works of all major representatives of Hungarian art and applied arts in the building.

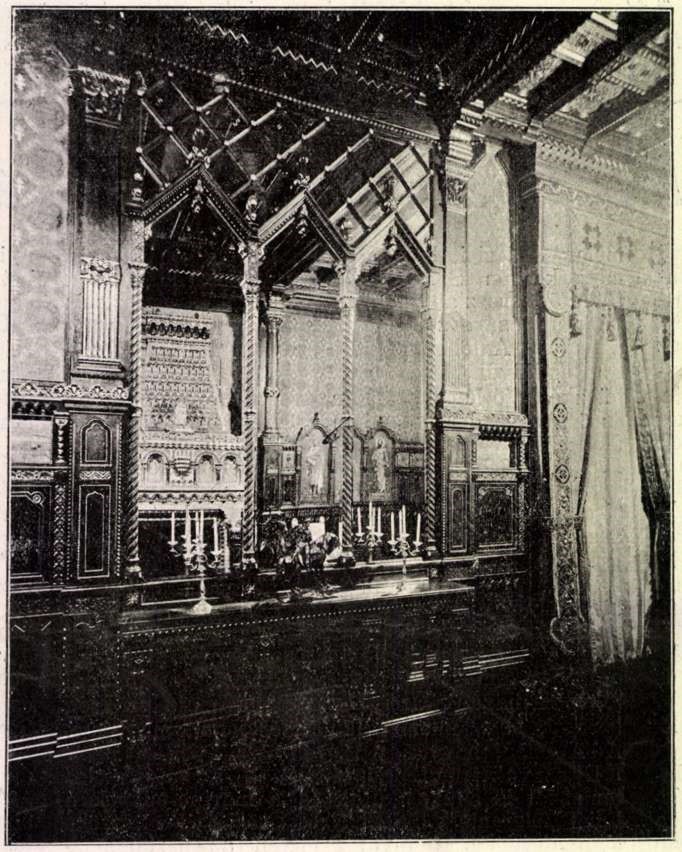

And where the Zsolnay ceramics could have had a better place than in one of the ceremonial halls commemorating the three great eras of the Hungarian historical past, in the St. Stephen's Hall, which symbolises the age of the Árpáds.

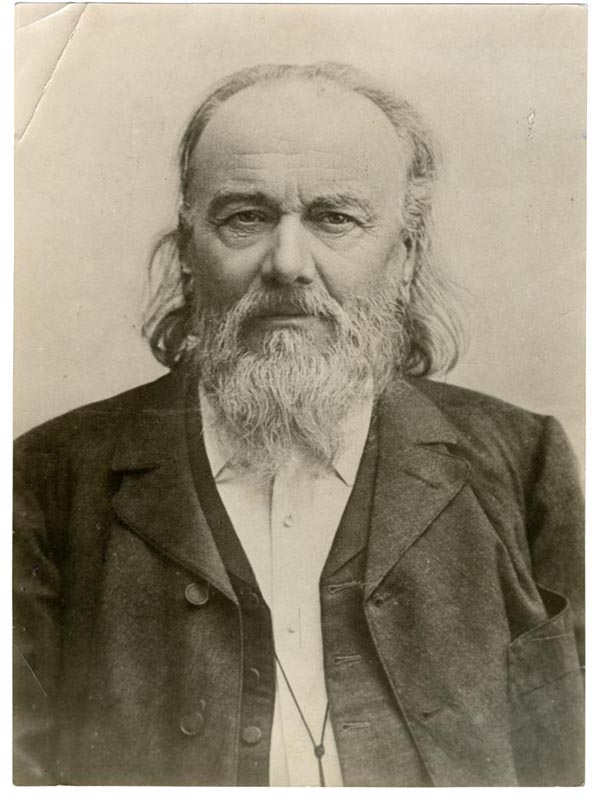

Zsolnay and Pécs - these words connected closely and deeply when in the middle of the 19th century Miklós Zsolnay founded his porcelain manufactory. As early as 1865, the factory came under the control of Vilmos Zsolnay, who proved his commitment and innovative spirit countless times, and whose imagination and commitment knew no bounds. Thus, it is no wonder that under his hands the factory has become not only the number one representative of architectural ceramics in Hungary but has also gained a reputation and prestige in the world..

The Pécs factory became the number one representative of architectural ceramics under the direction of Vilmos Zsolnay

The fireplace made of Zsolnay majolica, designed for the royal palace, is a great work of craftsmanship, a high-quality product of Hungarian industry at the turn of the century. Unique work, no copy found elsewhere. Its special shape is due to the medieval-style high flue.

“In the era when it was made, in Neo-Romanesque interiors and medieval castles, it was customary to build fireplaces with similarly high flues. At the same time, this work of the Zsolnay Factory is a stylized, elegant formulation of the rough, rustic heating of castles, harmonising with the royal palace,” says art historian Péter Rostás.

The elegant, stylized fireplace of St. Stephen's Hall in the Royal Palace of Buda in 1912 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

As the central work of St. Stephen's Hall, the fireplace stands on the north side of the room, opposite two south-facing windows overlooking Gellért Hill, between which Hauszmann designed a huge mirror. This made the room, which was only 72 square metres, look much larger, and it also essentially doubled the fireplace, as anyone who turned their back on it could see it in the mirror.

The fireplace was perfectly visible in the opposite mirror (Source: Ország-Világ, 6 October 1901)

In the hall, which symbolises the age of the Árpáds, it goes without saying that the coat of arms of the Árpád House appears on the fireplace, namely above the firebox on the front side, in a central position. It is much more surprising, according to experts, that the animal on the coat of arms really looks like a lion, as stylized versions reminiscent of dachshunds can be found on the coats of arms in other parts of the room.

Detail of the new Zsolnay Fireplace with the coat of arms of the Árpád House (Photo: Várkapitányság)

"The other decorative motifs in the Zsolnay work are the same as in the other parts of the St. Stephen's Hall: palmettes, rosettes, tendrils, flowers, hearts alternate and repeat," emphasises Péter Rostás, to which designer Tibor Angyal adds that "the whole room was lovingly made, including the Zsolnay fireplace, it can be seen in every element.”

The picture on the left shows the version of the Zsolnay Fireplace set up in the Thék Factory in 1900, while on the right, the redesigned chimney pipe can be seen in the factory of the Zsolnay Porcelain Manufactory, after the trial assembly (Photo: Várkapitányság)

The bust of St. Stephen was located on the main ledge of the fireplace: Alajos Strobl's work depicts our first king with the Holy Crown, although it was already common knowledge that Stephen could not wear this crown because it was made in much later times. According to Péter Rostás, however, we cannot call this solution an anachronism, we should rather consider it a symbolic representation. A similar solution can be seen on the ceramic tablets above the east door, where the Holy Crown also appears in the depiction of the coronation of St. Stephen.

Bust of St. Stephen in the hall of the Zsolnay Factory, the ceramic insert next to it is one of the elements of the front of the fireplace (Photo: National Hauszmann Program)

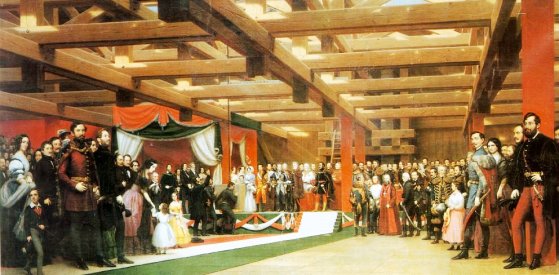

Before the fireplace was transported to the Royal Palace 120 years ago, it was assembled several times. After the main trial of the factory, it was first built in Endre Thék's factory in Budapest, Üllői Road, where the entire St. Stephen's Hall was assembled in preparation for the Paris World's Fair in 1900, and the king himself visited the masterpiece as well. It was then assembled in Paris at the World's Fair, which opened on 5 April 1900, where several of the hall's creators won gold medals. After the exhibition closed on 12 November, elements of the St. Stephen's Hall, including the Zsolnay Fireplace, were brought home from the French capital to be erected in its final location, the Royal Palace.

The great tragedy of fate is that Vilmos Zsolnay could no longer see perhaps the most mentioned masterpiece in the Buda Castle, although he had previously initiated to have a Zsolnay Room in the palace. He died on 23 March 1900, at the age of 72, three weeks before the opening of the World's Fair in Paris.

The St. Stephen's Hall in 1900, in the workshop of Endre Thék, in Üllői Road. The version shown in the picture was not the one realised in the Royal Palace: from the numerous differences, it is obvious that the fireplace stands on a podium and St. Elisabeth is not in her final place either (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

"It stood on a podium in the Thék workshop, and was located further out, but in its final location, in the palace, it was built on the parquet level and placed in a wall cabin. We cannot see the parquet in the photos made before the World Exhibition, so it is possible that it was not laid there, but there are numerous other differences between the two versions of the room, such as the images of saints and kings were in a different order later in the palace.” - details the architect expert.

The Zsolnay Fireplace was already the subject of admiration of many at the turn of the century. "I present the largest, most stylish and lavish fireplace ever made in Hungary, for the St. Stephen's Hall of the Royal Palace in Buda," said the author of the 15 February 1902 issue of the Magyar Üveg- és Agyagipar magazine. Seeing this masterpiece, he concluded that the Hungarian fireplace industry, which has recently undergone tremendous artistic and formal development, has a huge future ahead of it.

.jpg)

Drawing of the Zsolnay Fireplace in the 15 February 1902 issue of the Magyar Üveg- és Agyagipar

The contemporary papers depict Alajos Hauszmann, the designer and foreman of the Royal Palace, as the designer of the St. Stephen's Hall and the Zsolnay Fireplace. In essence, Hauszmann himself reported this in his diary notes when he wrote about the Paris World’s Fair as saying, “my plans have been awarded a Grand Prix”. But in an article published in the 3rd issue of Magyar Iparművészet in 1900, he wrote that he wanted to share the glory with Géza Györgyi, as “all the details of the room were done by my architect colleague Géza Györgyi, who drew these with a rare talent, and if we win, he should be entitled to the corresponding part."

.jpg)

Decorative motifs of the Zsolnay Fireplace. Originally probably drawn by Géza Györgyi (Source: Várkapitányság)

The Zsolnay work may have been the ornament of the Royal Palace in Buda for decades, and this may be expressed in the strictest sense of the word because they probably never set fire in it. At least to the best of our knowledge today, this seems the most likely. There was air heating in the ceremonial halls of the palace (supplemented by radiator heating in some places), the boiler room occupied a full level in the Krisztinaváros wing, from where the warm air was led to St. Stephen's Hall through air ducts.

In the northwest corner of the room, on the top level of the 240-centimetre-high wood panelling, warm air was blown through a beautiful decorative grille mounted in place of one of the ceramic inserts. On the other side of the fireplace, the rotten air was sucked through the decorative grille through an air duct in the attic to a group of roof chimneys in the Krisztinaváros Wing. The chimney of the fireplace, controlled by a damper, helped the ventilation by gravity.

The fireplace in the early spring in the Zsolnay factory, during the first trial set-up. They probably never set fire in the original fireplace (Photo: Várkapitányság)

It is well known that the fate of St. Stephen's Hall and the Zsolnay Fireplace was sealed by the senseless destruction of the last hours of World War II. And all that remained of the past, designed and executed with artistic demand, was mercilessly wiped out by the new power after 1945.

Since then, it has been incomprehensible to many that the greatest work of art of the era, the Royal Palace, whose architectural and cultural-historical significance can only be compared to the Parliament building, was destroyed, leaving only the bare walls.

It was designed with artistic demands but was destroyed in World War II and subsequent rage. The picture shows the detail of the re-created Zsolnay Fireplace (Source: Várkapitányság)

But there are those who, decades after what happened, thought that it was not necessarily necessary to put up with it, and perhaps it was worth bringing something back from the values destroyed. Already in 2001, art historian Péter Rostás suggested that it would be important to restore the St. Stephen's Hall and make it accessible as part of the palace history exhibition of the Budapest History Museum.

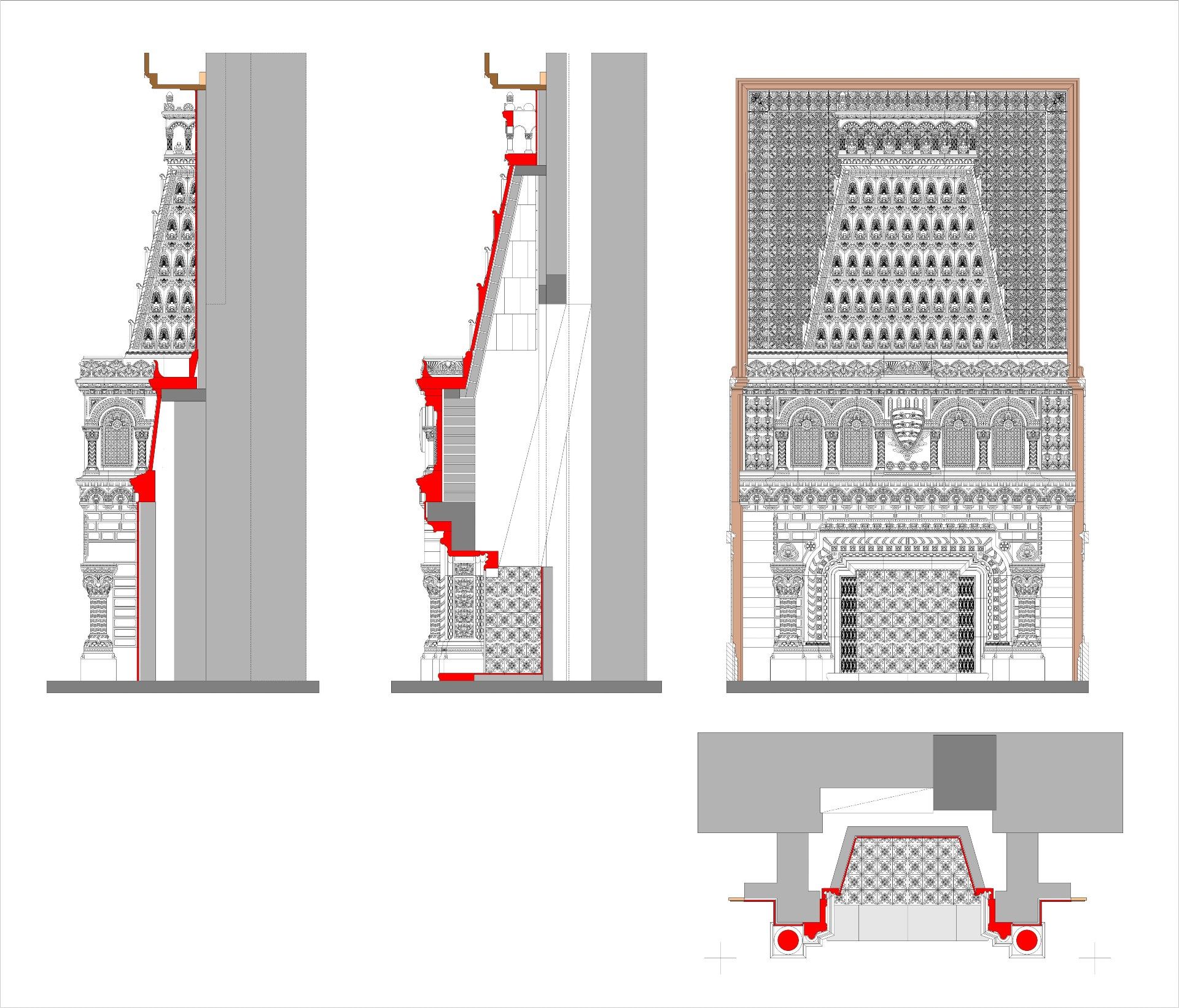

Finally, it was decided much later, in 2014, that the hall, including the fireplace, could be completed again as part of the comprehensive renovation of the Buda Castle District within the framework of the National Hauszmann Program. Among other things, everything had to be redrawn to start the complete restoration, and architect Tibor Angyal was commissioned to do this work. At first, it seemed like the task could take roughly three months, then slowly, it became clear to all participants that it was a much greater job than one might think, so the design work lasted for nearly four years from early 2016.

Construction of the new Zsolnay Fireplace in the Buda Palace in 2021. It was decided seven years ago to recreate it (Photo: Várkapitányság)

The question arises, if we know so much about the past, if a series of drawings, plans, countless high-quality photos, documents have survived, then why does the re-creation take so long that it will only be completed by 20 August 2021?

Péter Rostás draws attention to the fact that the first and most important rule in any reconstruction is to work based on photos. After all, even construction plans are not realised in the way they are drawn, so it is especially important to start from photographs, especially when redesigning ornamentation. This was also the case with St. Stephen's Hall and the Zsolnay Fireplace.

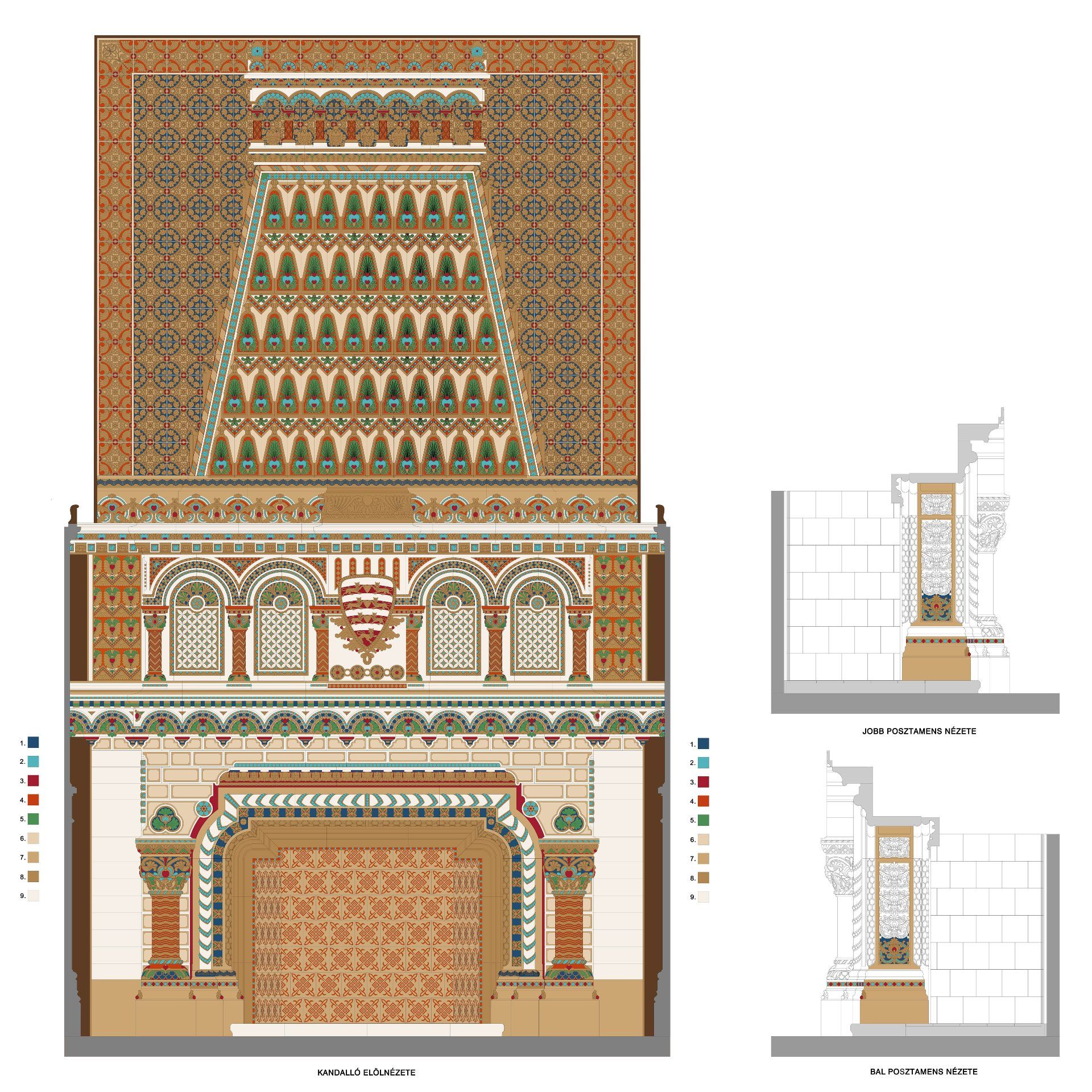

“I had to redraw every square inch of this fireplace based on the photos. A life-size original plan exists only for a fragment of the fireplace, and it does not always show the decoration and colours actually realised," - says Tibor Angyal.

The Zsolnay Fireplace had to be redrawn based on old photographs. The work of architect Tibor Angyal

All that was left of the past could not, therefore, replace redrawing based on photographs, but it greatly aided the process of reconstruction. Such were, for example, the trial burnings of the ceramic inserts of the fireplace preserved in the Janus Pannonius Museum in Pécs, or the duplicates of a good few elements of the fireplace found there.

For a long time after the destruction of the royal palace, one might think that nothing was left of the fireplace. Until a tile was found, which was found in the building debris by a little girl in the 1960s, and a few years ago it was collected by Péter Rostás for the Kiscelli Museum. The child, blessed with a sense of beauty, did a great service, as the chimney tile she preserved for decades was the only intact piece of the destroyed Zsolnay Fireplace, and during the current reconstruction, it proved the colours previously determined by the museum chimney pieces.

The only surviving piece of the original Zsolnay Fireplace in St. Stephen's Hall was unearthed a few years ago (Photo: Várkapitányság)

The most difficult task was to determine the colouring system, as only black and white photographs of St. Stephen's Hall and the fireplace remained. Indeed, all nine applied shades (the eight colours and the gilding) were found separately on the museum specimens, but the photographs had to be used to determine which of the colours was used in which place.

The examination of the archival images, the analysis of the colour function and the study of the sensitivity of the contemporary photo raw materials helped the most, in addition, of course, the remaining trial burns and the mentioned single original tile contributed to the success of the end result. The work of Tibor Angyal was assisted in the preparation of the colour plan by architect, painter-restorer Boglárka Szentirmai, with whom they found out the original places of application of the colours.

Reconstructive colouring plan of the fireplace covering all elements, made by Tibor Angyal and Boglárka Szentirmai. Based on this, the production and colouring technology of fireplace elements was developed in Zsolnay Porcelánmanufaktúra Zrt.

Even though many excellent photographs were taken of the fireplace, its depiction is not complete. "The fireplace stands in a booth, and there are nooks on both sides, it is not possible to see the decoration perfectly on the 60x30 cm tiles sloping inwards.” - Tibor Angyal shared. “Although the system of decoration can be recognised on these as well, the details cannot be taken out. In the rest of the fireplace, all patterns, leaves and berries could be counted and read, but the tiles that were not clearly visible had to be sampled from elsewhere. Fortunately, this problem affected only two pieces of the nearly one-and-a-half-ton, 611-element fireplace,” - he said.

Hearts, berries, flowers. The decoration system was recognisable in the old photos, only the details of two tiles cannot be known (Photo: National Hauszmann Program)

Behind these dry facts and figures lies a tremendous determination, perseverance, commitment. Art historian Péter Rostás and architect Tibor Angyal could talk for hours about how many nights they had to spend studying drawings, pictures, and all sorts of other documents. How many conversations during day and night contributed to the finalisation of the tiniest elements of the re-creation. How this story captivated the participating artists, how their workshop, apartment and life have been occupied by a task that requires commitment, which others simply call the reconstruction of St. Stephen's Hall.

They came a long way to this day, but here we are, the 2.8-metre-wide and 4.7-metre-high fireplace made in the Zsolnay Porcelain Manufactory in Pécs is being built in the Buda Palace. It will be similar to the original, but there will be so many changes that it will not be heated, unlike the former work. The air heating in the newly created St. Stephen's Hall will work in a similar way to the original but treated air will also be blown into the room through the fireplace.

The fireplace is cleaned and dusted in the palace during assembly in 2021 (Photo: Várkapitányság)

During the ongoing interior design of the St. Stephen's Hall, pyrogranite paintings (also painted based on oil paintings made by Ignác Roskovics), also made in the Zsolnay Porcelain Manufactory, will also be incorporated, depicting rulers and saints of Árpád House, including two scenes from St. Stephen's life. In addition, the walnut wall cladding's ceramic inserts made in Pécs will also be installed.

The 360-centimetre-long ceiling ceramic insert is placed symmetrically on both sides of the fireplace (Photo: National Hauszmann Program)

When this special hall opens on 20 August 2021 as an important result of the National Hauszmann Program, the public can revisit the value of Hungarian history and Hungarian culture that has been soullessly and meaninglessly destroyed. What can be expected was articulated by Alajos Hauszmann when he presented the St. Stephen's Hall made for the Paris World's Fair to the readers of the Magyar Iparművészet in 1900:

“I have to pay the greatest recognition to the excellent artists and craftsmen who contributed to the creation of this work and made such a work in terms of the material used and the quality of the work which I think will be recognised abroad, honouring the Hungarian industry."

Details of the new Zsolnay Fireplace (Source: Várkapitányság)

Cover photo: The St. Stephen's Hall in the Buda Castle (Source: Budapest History Museum)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration