One of Miklós Borsos' best-known works is the Zero Kilometer Stone at the Buda bridgehead of the Chain Bridge, Clark Ádám Square, the alpha and omega of Hungarian road traffic. The kilometre stone erected on 4 April 1975, represents zero with a real zero. In the 26 April 1975 issue of the Film Színház Muzsika, the artist states:

“People with some weird split consciousness always want to come up with something or say something different than what it is about. I know that zero kilometre stones are marked everywhere with a statue of one kind or another. Although this is an international sign, it is very important that anyone who looks at it recognises it. If we were to put Venus de Milo in its place, it would flood the square with beauty, but suddenly, it might not prevent us from avoiding a traffic disaster. And just look: zero is actually a beautiful exclamation point!”

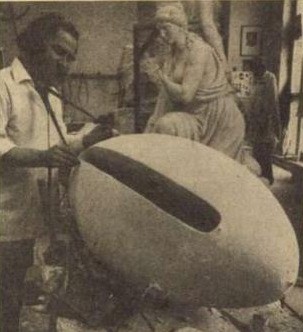

Miklós Borsos while making the Zero Kilometre Stone (Source: Hajdú-Bihari Napló, 21 February 1975)

The work of Miklós Borsos, the Zero Kilometre Stone in Clark Ádám Square in 1975 (Source: Fortepan/UVATERV)

The work of Miklós Borsos, the Zero Kilometre Stone in Clark Ádám Square in 1975 (Source: Fortepan/UVATERV)

The kilometre stone represents zero with a real zero (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The most striking feature of the Zero Kilometre Stone is the characteristic centreline, which is also a “trademark” of other significant works by Borsos. In his spare time, the artist, who also played the violin and collected preclassical scores, commented on the musical parallel of this in the July 1965 issue of Muzsika:

“And that is also the result of some weird, transmitted musical effect or musical imagination. I played the violin in my youth and as I pulled the E-string on the violin, this tense high string appears as the centreline of most of my sculptures. The whole existence and essence of these places or figures are defined by a positive, sometimes negative arc from the forehead, which gives character and is the only part of the sculpture that cannot be changed or otherwise shaped. And that is what I do every time, it is always like I am playing the E-string of the violin.”

The Bimbó Fountain in the southern courtyard of the Buda Castle; the characterised centreline appears here (Photo: Róbert Juharos/pestbuda.hu)

The Heart

In front of the Haller Street main entrance of the Gottsegen György National Cardiovascular Centre (formerly known as the National Institute of Cardiology), in the front garden stands Miklós Borsos's perhaps most enigmatic and significant work in the field of cardiology iconography, The Heart. Standing on a white marble pedestal, inaugurated on 30 June 1976, the large, grey-coloured work is autobiographically inspired: in 1973, the artist recovered from a serious heart problem thanks to surgery.

Miklós Borsos's statue, The Heart at the main entrance of the Gottsegen György National Cardiovascular Centre (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Before his life-saving heart surgery, Miklós Borsos turned to the doctors with a request that the cut be on his chest, not on his neck. Namely, he could play the violin again only with this solution (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Well of St. Francis

The central element of Miklós Borsos' oeuvre is the deeply lived and undertaken faith. The vast majority of his works are inspired by the Bible and Christianity: he did not let go of his principles even when he, therefore, fell into the tolerable category. He was preoccupied with the figure of St. Francis until the end of his life: he was an inspirer of sculptures, bronze medals and graphics, of which he states in the November 1982 issue of Vigilia:

“He was my only Christian ideal since my youth. … He was not a priest. He was not a Church Father. “Poverello” was a “no one”: God’s poor. But he uttered the greatest in the hymn. The unity, the identity, the divine law of the world, of creation, of being. Could a larger one be described in the thirteenth century? He is the greatest liberator of the human spirit and soul. It keeps him alive for eight hundred years, and it will keep him alive as long as the human soul and thought long for freedom and reject the shackles that Power always places on it.”

One of his most significant works depicting St. Francis is the Well of St. Francis, made in 1947 and donated by the artist to the Franciscan Monastery in Pasarét. The formation of a glorious, bird-holding figure in the middle of the rectangular monastery garden, reflecting the closeness of God and nature - in the context of the well symbolising “living water” - is characterised by a kind of inner intimacy and personality.

Borsos' art was decisively determined by his youthful journey to Tuscany, Italy and the renaissance harmony of the works of art and urban architecture seen at that time. The statue of St. Francis also reflects this sense of life in Central Italy.

Arcadian atmosphere in the Lágymányos housing estate

"Getting acquainted with the often striking, sometimes bizarre formal ideas of modern art, I was looking for an even simpler form of expression, and I found this in the very old statuary ... the source: Greece," wrote Miklós Borsos. This is evidenced by the smaller, horizontal relief called Bacchus (with a pitcher on the side next to the head of the lying figure and a bunch of grapes spanning over it) and the vertical, Women at the Well (three young female figures, one holding a child; two "pigeons of peace" above the well) rectangular limestone relief made in 1959. No other than in a residential house in Lágymányos at 7 Október 23 Street.

Works by Miklós Borsos in a residential house in Lágymányos. Above the entrance to the shop, a relief called Bacchus can be seen: with a pitcher on the side next to the head of the lying figure and a bunch of grapes spanning over it. On the facade opposite it is a relief called Women at the Well (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Works by Miklós Borsos in a residential house in Lágymányos. Above the entrance to the shop, a relief called Bacchus can be seen: with a pitcher on the side next to the head of the lying figure and a bunch of grapes spanning over it. On the facade opposite it is a relief called Women at the Well (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Relief by Miklós Borsos: Women at the Well. Three young female figures, one holding a child; two "pigeons of peace" above the well (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

This Arcadian, “Apollonian” spirit, emphasized by its diagonal structure and contrast of dimensions, is completely foreign to socialist realism. In the March 1961 issue of Művészet, Borsos received the verdict from the official cultural policy: "Escape to the heights of "Parnassus" from the reality of everyday life does not in any way make the works fit to meet the needs of our new society, in a new housing estate."

Sun disc with a female figure, made by Miklós Borsos, in the 8th District at 28 Üllői Road (Photo: Róbert Juharos/pestbuda.hu)

The Transylvanian roots - the statue of Antal Budai Nagy

The Szekler origin of the artist (his family enriched the culture with such significant artists as the sculptors László Paál and Miklós Köllő) and his Transylvanism give personality to the large bronze bust of Antal Budai Nagy, which stands in the hall of the grammar school in Budafok named after the leader of the Transylvanian peasant revolt against King Sigismund in 1437-38.

Bronze statue of Antal Budai Nagy at the Antal Budai Nagy Grammar School in Budafok (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Borsos seemed to have modelled the large head of an ageing man, who radiated moral support, repressed systems and fought against them, based on himself. In the 28 August 1977 issue of Ország-Világ, he summarised the process of preparation as follows, highlighting Károly Kós's short novel The History of Antal Budai Nagy:

“I have been looking for the motif for the depiction of Antal Budai Nagy for more than a year. I read Károly Kós's book and much more, I looked at several contemporary Szekler depictions. The lessons learned will lead to the creation of an authentic statue, which will be erected in Óbuda.”

Instead of Óbuda, the Budapest Monument Inspectorate designated the high school in Budafok as the site of the statue, so it was erected there in 1878.

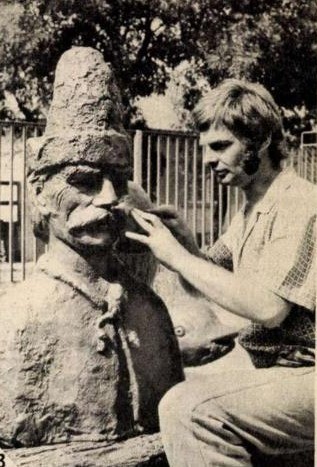

The Antal Budai Nagy sculpture of Miklós Borsos is made in the sculpture foundry of the Fine Arts Executor Company (Képzőművészeti Kivitelező Vállalat) on Barabás Street (Source: Turista Magazin, October 1978)

Role and performer: Gilda and Mária Gyurkovics

The tombstones designed by Miklós Borsos represent a significant part of his oeuvre. Looking at both the oeuvre and the list of tomb sculptures, it is striking that prominent stage personalities of contemporary acting and opera performance do not appear in his works. Yet, theatre and music were close to the artist: in 1965, he designed sets for the National Theatre for the Oresteian Trilogy of Aeschylus. From the world of music, his real fields were the pre-classical era, violin literature and chamber music: Bach (mainly solo sonatas), Vivaldi, Purcell, Händel, Gesualdo, Monteverdi, Palestrina.

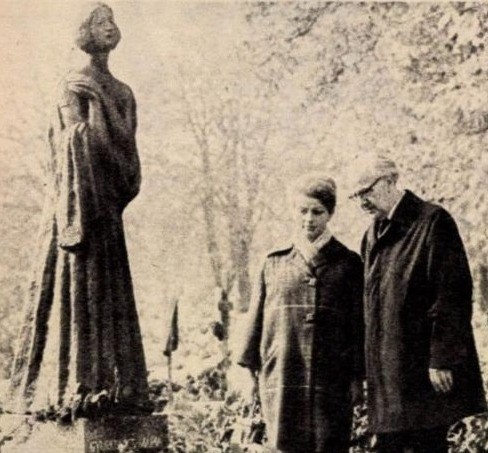

Tomb of opera singer Mária Gyukovics, in front of it her husband, Miklós Forrai and daughter, Zsuzsa Forrai (Source: Film Színház Muzsika, 5 November 1977)

At the same time, Miklós Borsos made a tombstone for the excellent coloratura soprano Mária Gyurkovics. Plus, with her best-known role, Gilda, from one of the most popular pieces in Italian romantic opera literature, Verdi’s song Rigoletto. The sculpture in the 25th parcel of the Farkasréti cemetery, inaugurated on 28 October 1977, reflects the finding and harmony of the performer and the character she formed. The female figure also faithfully evokes the world of the Renaissance.

The figure of Gilda on the tomb made by Miklós Borsos (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The female figure also faithfully evokes the world of the Renaissance (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The female figure also faithfully evokes the world of the Renaissance (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

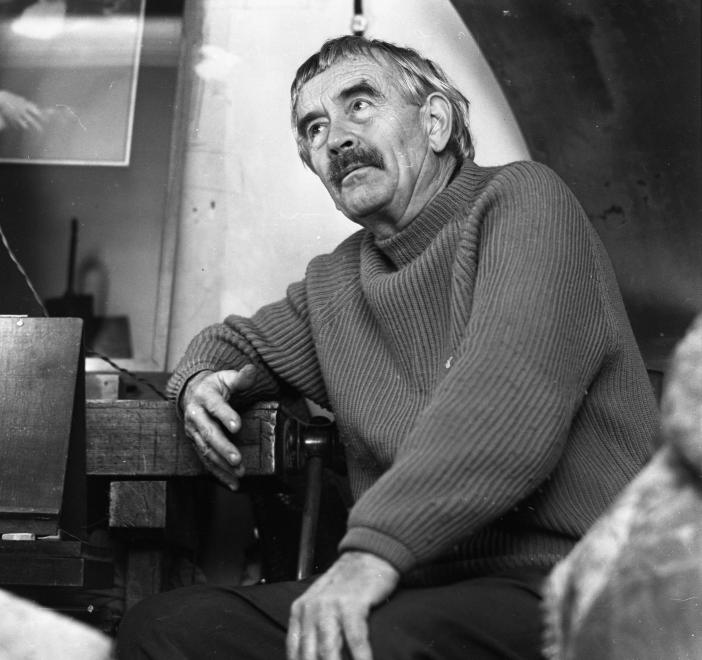

Sculptor Miklós Borsos in his studio, in 1972 (Source: Fortepan/No.: 87957)

Miklós Borsos spoke about himself in an interview published in the book From the Tower (A toronyból), in 1979:

“We read Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Marx at the time, but I did not get the answer from philosophy about life, behaviour. I never needed to ask anyone, say at the beginning of Hitler’s time, when the Reichstag was set on fire, whether it was good or bad. I knew exactly. I grew up reading the Bible, and with that upbringing, one always knew exactly what was good and what was bad.”

Cover photo: The Zero Kilometre Stone nowadays in Clark Ádám Square, in the background the Buda Castle Funicular (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration