The word Curia [Kúria in Hungarian] is of Latin origin and refers to a judicial activity at the seat of the king (Latin in Curia Regis). The Hungarian Royal Curia was established as an institution in 1723, but moved to its first independent home only in 1804: to a one-storey, classicist building on Ferenciek Square in Pest. Due to its poor appearance, it was not worthy of the authority of the high office at all, so in 1868, on behalf of the Minister of Justice Boldizsár Horváth, the architects of Antal Szkalnitzky and Henrik Koch prepared plans for a new building, but the construction was delayed. As a novice architect, Hauszmann, returning home from his studies in Berlin, worked in this very office and was involved in the design.

The old building of the Mansion in Ferenciek Square (Source: Alajos Hauszmann: A budapesti Igazságügyi Palota. [The Palace of Justice in Budapest] Budapest, 1901)

The old building of the Mansion in Ferenciek Square (Source: Alajos Hauszmann: A budapesti Igazságügyi Palota. [The Palace of Justice in Budapest] Budapest, 1901)

The case came to the fore again in the early 1890s, when the planned construction of the Elizabeth Bridge re-regulated the street network of the Inner City in Pest and ordered the demolition of several buildings, including the one that housed the Curia. In November 1891, Hauszmann was commissioned to design a new building, in which, in addition to the Curia, the Budapest Court of Appeal had to be located, because its seat also fell victim to regulation. The decision to marry the two institutions was taken mainly for budgetary reasons. Later, even the offices of the Royal Prosecutor General's Office and the Crown Prosecutor were moved here. The old building was indeed demolished in 1895, but its memory is still preserved by the name of Curia Street.

Ferenciek Square (Kígyó Square) house number 3, next to the left is the building of the Curia. During regulation, the entire block was demolished. (Source: Fortepan / Budapest Capital Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.052)

Ferenciek Square (Kígyó Square) house number 3, next to the left is the building of the Curia. During regulation, the entire block was demolished. (Source: Fortepan / Budapest Capital Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.052)

Considering its function closely related to the king, it would have been obvious to place the Curia in Buda, next to the Royal Palace, but the Budapest Court of Appeal needed a more accessible place. The latter claim was victorious and a worthy plot of land was finally found opposite the Parliament for the building, dubbed the Palace of Justice. Its prestigious appearance was augmented by the fact that it stood free on all four sides: Nádor, Alkotmány, Honvéd and Szalay Streets.

According to the remarks of the building committees, Hauszmann made the final, modified plans in the summer of 1893, and wrote about his position in his book A budapesti Igazságügyi Palota [The Palace of Justice in Budapest] as follows:

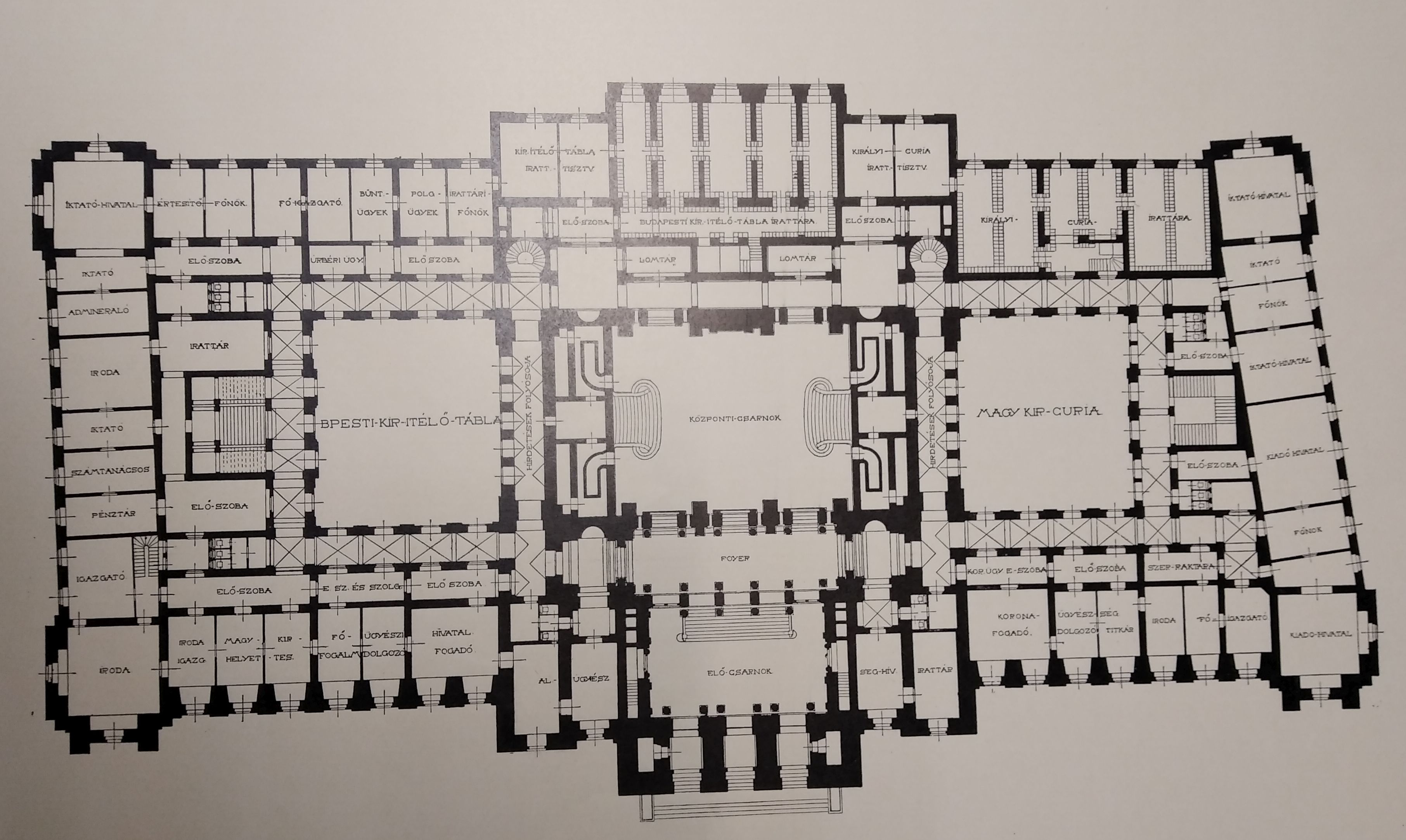

“The space requirements of the Royal Curia and the Budapest Court of Appeal were approximately equal, and so the layout could be nothing else but placing the Supreme Court [the Curia - Ed.] in one half of the building, around a separate courtyard, and group the premises of the Court of Appeal to the other one, symmetrically, and the central part of the building would contain entrances, halls, ceremonial halls, stairs, etc. "

Ground floor plan of the Palace of Justice, with the huge hall in the middle (Source: Alajos Hauszmann: A budapesti Igazságügyi Palota)

Ground floor plan of the Palace of Justice, with the huge hall in the middle (Source: Alajos Hauszmann: A budapesti Igazságügyi Palota)

The building actually has a roughly rectangular floor plan, the longer side of which runs parallel to the Parliament. The 125-meter main façade has extremely wide protrusions (risalits) in the middle and much narrower protrusions at the corners, and the same can be observed on the slightly shorter rear façade due to the irregularities of the site. In the middle of the building is a huge hall, 40 times 18 meters side length, which is made really impressive by its 24 meter height. With its perfect harmony of space and huge vault, which have a classical effect, the baths of the Roman emperor Caracalla could be seen as the forerunner. This hall connects the offices in the two wings and also served as a waiting room for the public.

The huge hall dominating the center of the building was modeled on Roman baths (Source: Ethnographic Museum website, neprajz.hu)

The huge hall dominating the center of the building was modeled on Roman baths (Source: Ethnographic Museum website, neprajz.hu)

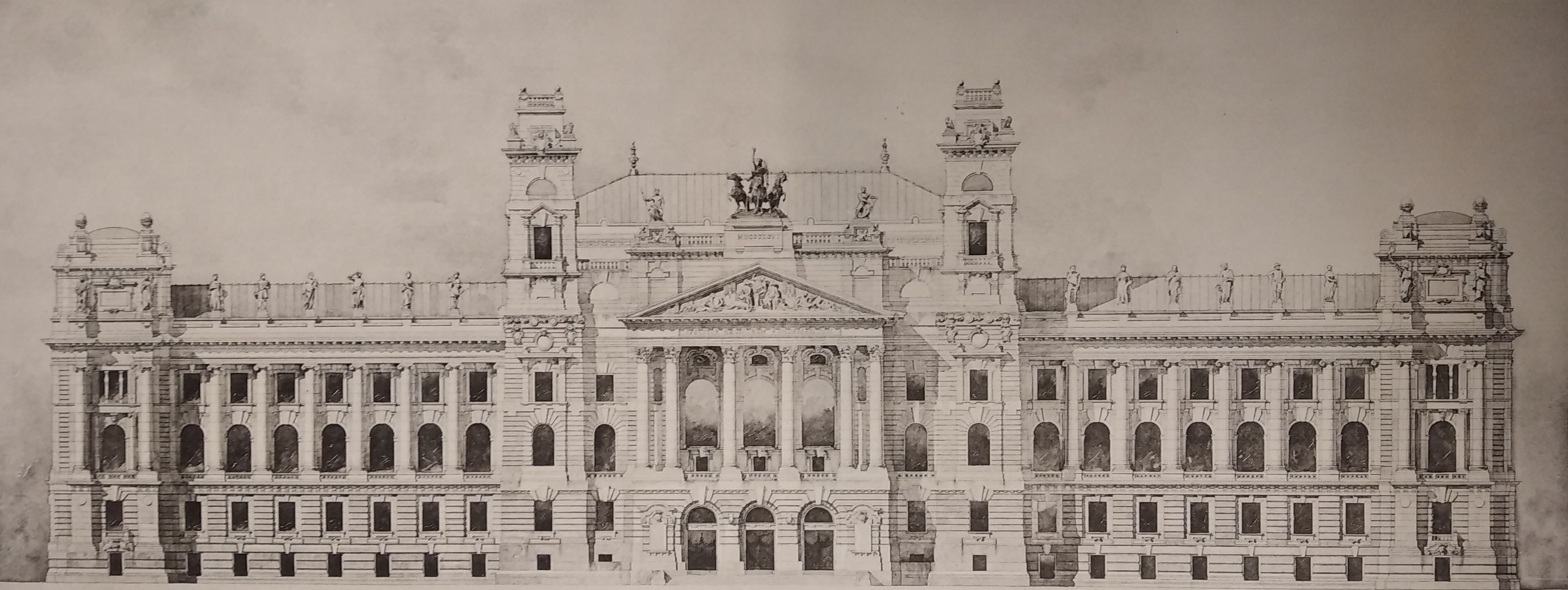

In front of the great hall, in the central axis, there is another smaller foyer and a connecting space, into which the road leads through the triple gate of the central risalit. Above the lobby, on the first floor, is the ceremonial hall, with huge windows opening onto a balcony in the central risalit. The large hall in the central axis is also projected by the façade: a huge gate (portic) of six Corinthian columns closing at the top in a tympanum elevates the monumentality of the main façade and suggests a similarly grandiose interior.

Plan of the main facade of the Palace of Justice (Source: Alajos Hauszmann: A budapesti Igazságügyi Palota)

Plan of the main facade of the Palace of Justice (Source: Alajos Hauszmann: A budapesti Igazságügyi Palota)

Next to the gate, on each side of the central risalit, is a helmetless tower, and at the top of the corner risalits are wide but low towers (pylons). In terms of these basic forms, the model of the building could almost certainly have been the building of the Berlin Parliament, i.e. the Reichstag designed by Paul Wallott and built between 1884 and 1894 (the architect was, by the way, Hauszmann's fellow student in Berlin). At the same time, the Hungarian Parliament opposite the building also influenced its appearance: it could not compete with it, so it wanted to stand out by behaving in the opposite way. While the Neo-Gothic Parliament is characterized by upward-sloping towers and a roof, the Palace of Justice was designed in Roman Baroque style by the designer, which can be seen in the flat roof and powerful horizontal ledges.

Paul Wallott: The Reichstag building in Berlin at the beginning of the 20th century (Source: Fortepan / No.: 9041)

Paul Wallott: The Reichstag building in Berlin at the beginning of the 20th century (Source: Fortepan / No.: 9041)

The façade is complemented by a number of sculptural ornaments: the tympanum features the work of György Zala, which consists of three parts. In the middle, a court hearing appears, and in the two corners allegorical figures of the Legislature and the Doctrine of the Law sit. On the wall (attic) above the tympanum stands a chariot with three horses and the allegorical figure of Genius. The work of Károly Senyei was modelled on the four-horse Roman triumphal chariots, but a horse was left out due to the scarcity of space. In the hands of the female figure standing on the chariot, there are the torch of enlightenment and the palm of peace.

The three-horse chariot on the top of the building and the figure of the Genius by Károly Senyei (Photo: Balázs Both / pestbuda.hu)

The three-horse chariot on the top of the building and the figure of the Genius by Károly Senyei (Photo: Balázs Both / pestbuda.hu)

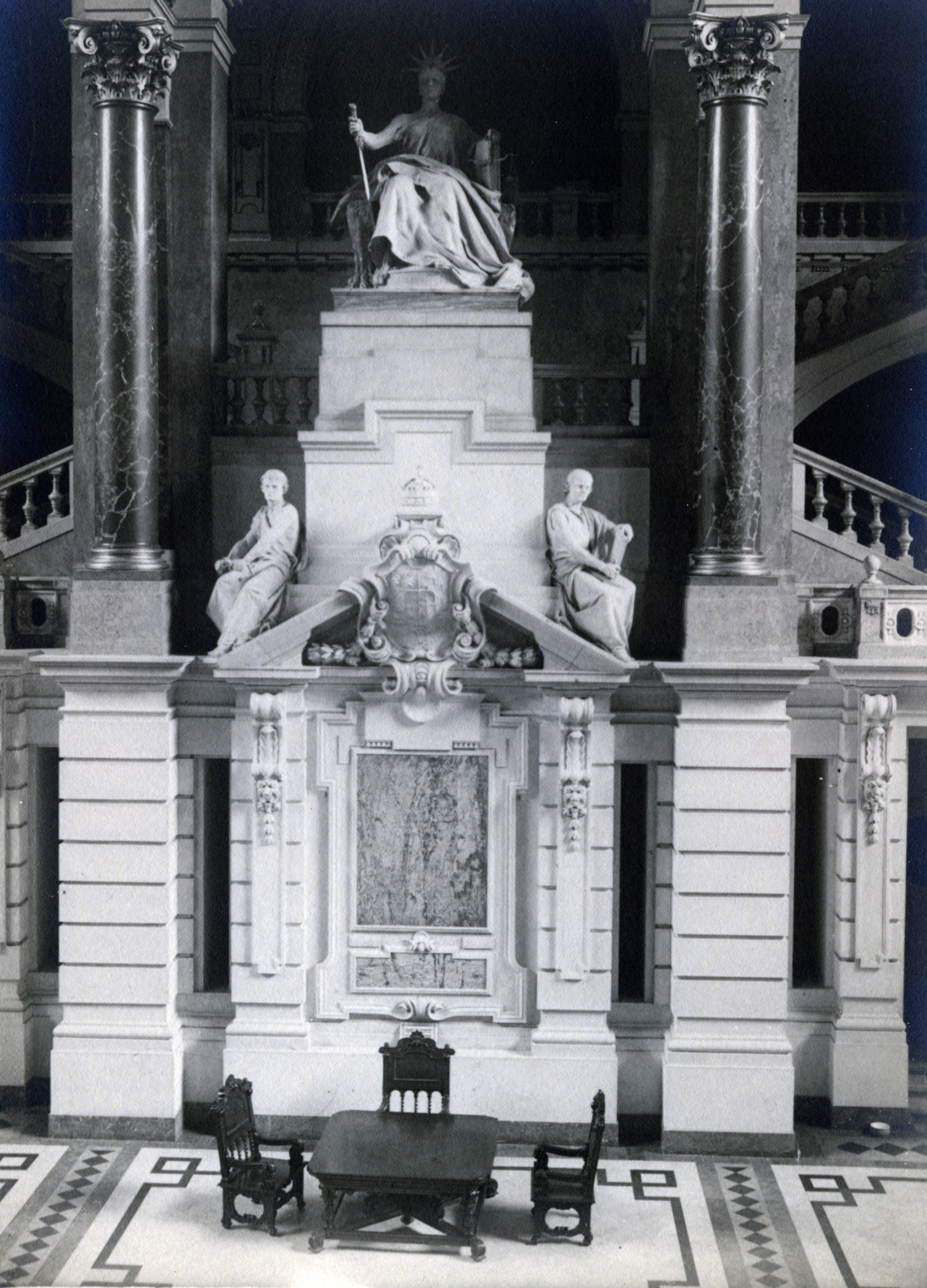

Inside, most of the artwork was placed in the great hall. Its two-hundred-square-meter vault is decorated with a painting by Károly Lotz, with figures depicting the overwhelming power of justice on the left, allegorical figures of the protective power of the law on the right, and the Roman god of truth, Justitia, surrounded by visible glory. Thanks to Alajos Stróbl, the goddess also appeared as a statue: opposite the entrance, she sat on a throne placed on a high pedestal, holding a scale and a sword in his hand.

The huge ceiling painting is the work of Károly Lotz (Source: Ethnographic Museum website, neprajz.hu)

The huge ceiling painting is the work of Károly Lotz (Source: Ethnographic Museum website, neprajz.hu)

The huge, eight-ton work of art was removed in 1950, as the function of the building changed: in 1957 the Hungarian National Gallery and then in 1975 the Ethnographic Museum moved within its walls, but the institution closed at the end of 2017 and moved out of the building completely last year. It will soon be able to take possession of its brand new building in Városliget, so the Curia can move back to its monumental home, and with it the statue of Justitia will return.

Statue of Justitia in its original place in 1935 (Source: Fortepan / 165473)

In the cover photo, the Palace of Justice nowadays (Photo: Balázs Both / pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration