It has been done. The blackest Friday. The mourning Budapest. The treaty of robbery, the treaty of mourning, treaty of violence. It is the worst and most humiliating work of all time. The death sentence of Hungary. Titles and expressions from the Budapest papers on the days of the signing of the Treaty of Trianon. The writers of editorials and reporters sought the saddest expressions of shock. There was deep pain in those days that could not be described in words.

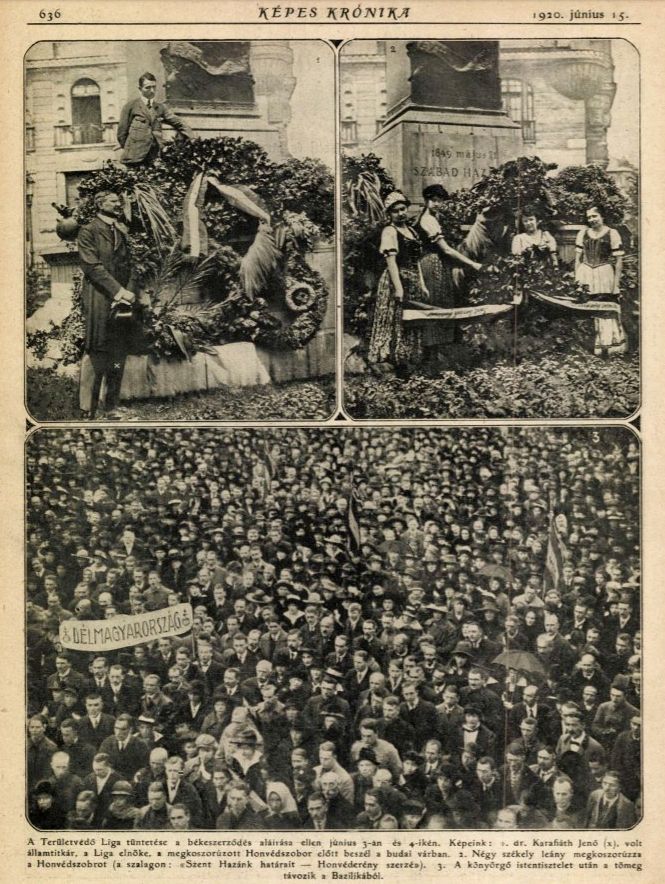

Demonstration by the Hungarian Territorial Integrity League against the signing of the peace treaty on 3-4 June, Photos: 1. Dr Jenő Karafiáth, former Secretary of State, President of the League, speaks in front of the wreathed Honvéd Statue in the Buda Castle. 2. Four Szekler girls wreath the Honvéd Statue. 3. After the praying service, the crowd leaves the basilica (Source: Képes Krónika, 15 June 1920)

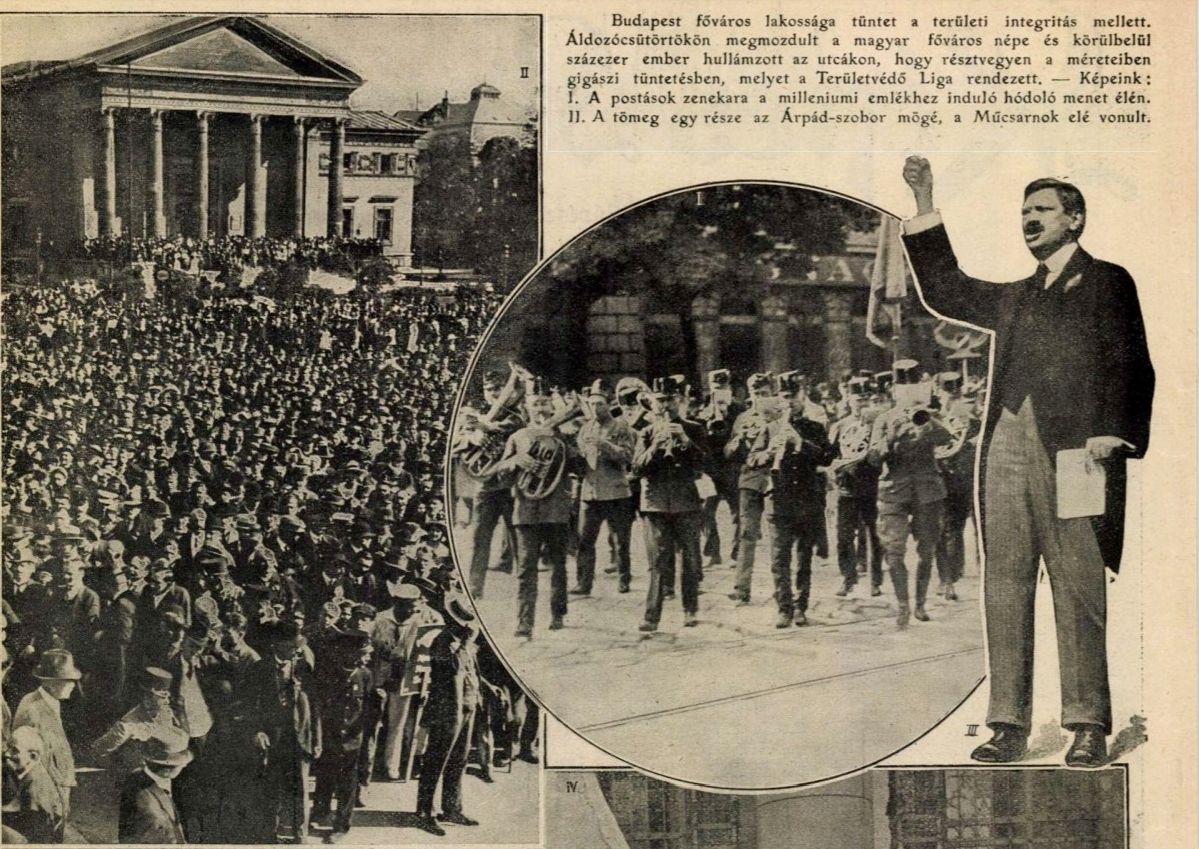

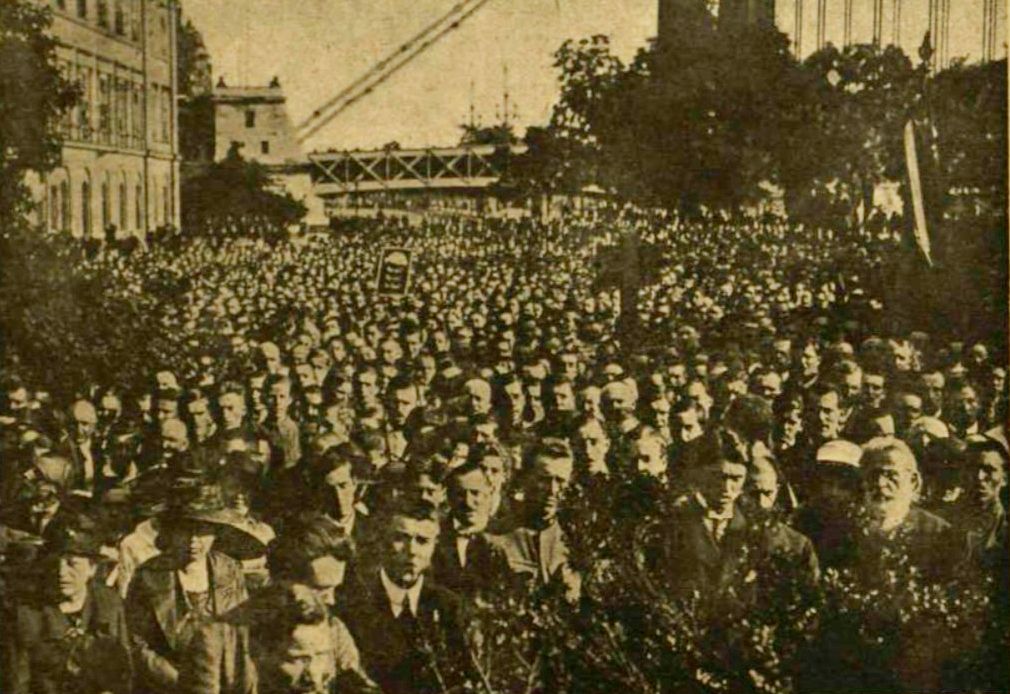

The population of Budapest protests for the territorial unity of Hungary, against the peace treaty (Source: Képes Krónika, 25 May 1920)

The upholstery of heaven is splitting

The Treaty of Trianon will be the most hated and humiliating document in the history of Europe in the 20th century, the Budapesti Hírlap led by Jenő Rákosi wrote before the signing. The Pesti Hírlap likened what was happening to Hungary to the Mohács disaster: “Then the wild hordes of the East trampled us to defend the West. Now the West thanks us with dividing our country”.

The paper Magyarország called the peace treaty the greatest injustice in history, which is signed with the blood of their hearts by the Hungarians who were appointed to it but forced to do so by brutal violence.

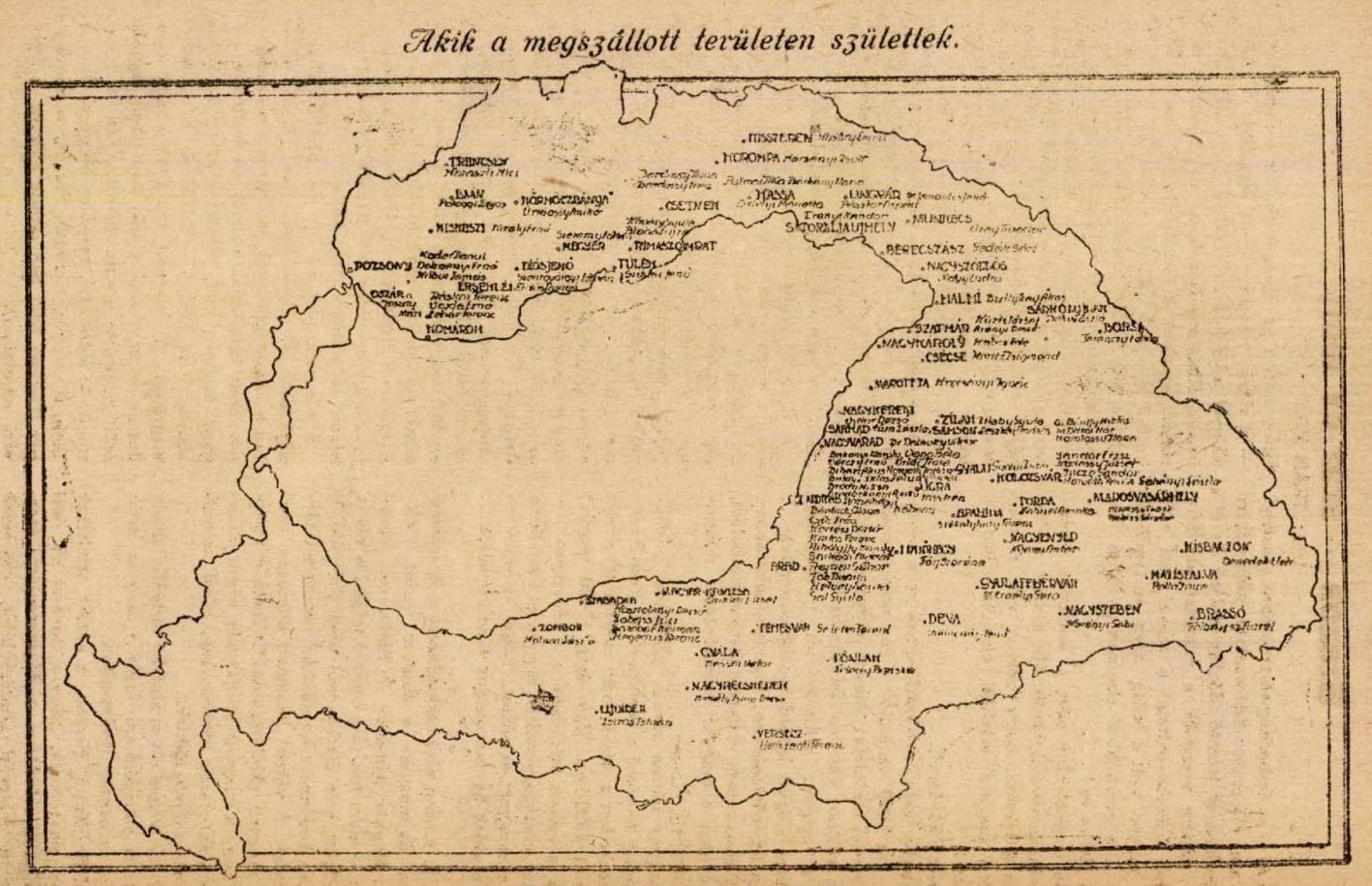

A map was published in the 15 February 1920 issue of Színházi Élet, which shows how many Hungarian artists and writers were born in the parts of the country that were doomed to secession. Count Albert Apponyi took the latest issue of Színházi Élet with him to Paris and attached it to the files of the peace negotiations (Source: trianon100.uni-nke.hu)

The capital was prepared for a silent demonstration on 4 June, but the movements had already begun on Thursday, 3 June. It was Lord’s Day, a great celebration of the Catholic Church. The people of Budapest planned that after the procession, they would visit the statue of Petőfi and Vörösmarty, the tomb of Kossuth, with a green twig of hope and a flower. "By appreciating the national past, we signal our faith in the future of a nation and our determination to fight for it," Pesti Hírlap wrote.

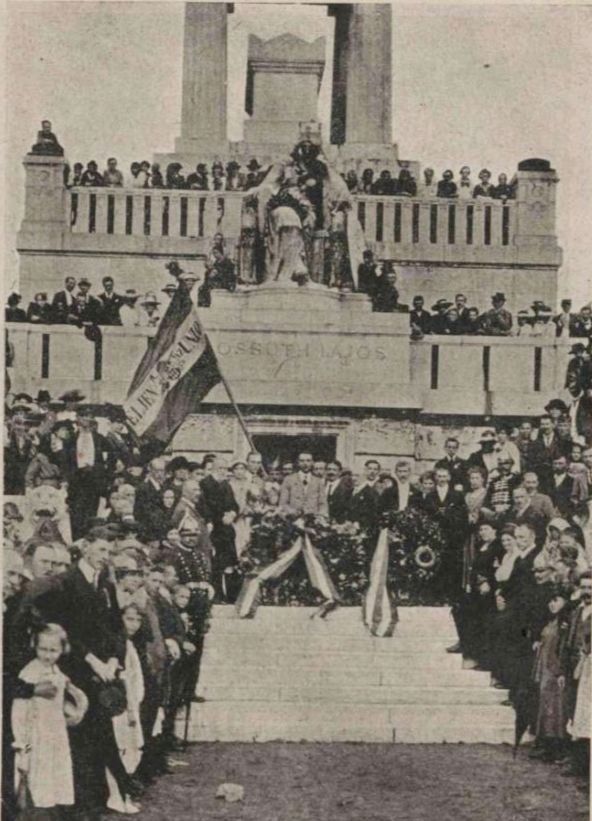

The Hungarian Territorial Integrity League lays a wreath over the Kossuth Mausoleum (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 27 June 1920)

The next day’s parade was named in the same newspaper as an appeal to the subjugated nation, protesting the unjust death sentence. “On the day of the signing of the murderous peace treaty, all life stops for minutes, trade, traffic and the heartbeat of the nation stops. With this, we are silently protesting against the divide of Hungary" - wrote the article's author.

The protesting crowd in front of the Millennium Monument (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 23 May 1920)

“Tomorrow the Hungarian sky will mourn, and the music will die, the word will drown on all Hungarian lips. Tomorrow, trains will stop all over the country and the beat of our hearts will stop on the gloomy feast of mourning. Tomorrow all the sons of this earth will wait for the tapestries of heaven to split and the earth, the abducted Hungarian land, to be shaken under the feet of the receiver. We were waiting for some miracle, some mighty justice that will thwart at the last moment the terrible sin woven by underground powers against us and all of humanity.” - said the journalist of the Világ on the day before the signing of the peace treaty.

There were no people and no newspaper in Budapest who would have thought otherwise.

The arrival of the girls carrying the wreaths on the Heroes' Square in front of the statue of Árpád at the Millennium Monument (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 23 May 1920)

Budapest is mourning

Then came the day, 4 June 1920, but every Hungarian wished it had never arrived. It was a Friday, a cool wind blew in Budapest that morning, and later it rained - it turns out from the papers of the time. The shops had to be closed between 10 am and 2 pm that day, but almost no one opened in the morning. Budapest mourned.

“Cafes and restaurants were also demonstrating with sealed shutters. At ten o'clock the trams stopped.” - Népszava reported. "The silence of the iron folds, the lost business and commercial life on the streets of Budapest today indicate what is happening in Versailles," wrote Az Est. A ban on alcohol was ordered that day, and no performances were held in any theatre in the capital, and the nightclubs were closed.

Work in the offices and banks was suspended, and the stock exchanges were kept closed. The trams did not move at 10 o'clock for 10 minutes. Trains across the country stopped for five minutes. The bells rang throughout the country at 10 a.m., warning the Hungarian nation of the blow being stroked on it in Paris.

Heroes' Square, Millennium Monument, wreathed a statue of Chief Árpád. Protest of the Hungarian Territorial Integrity League against signing the peace treaty (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 23 May 1920)

Although the children went to school, the teachers did not hold classes but told the students about the injustice forced on Hungary, and with tears in their eyes, they talked in a sobbing voice about their thoughts on the fate of the country which were more important than any subject.

The participants of the silent demonstration, including the people expelled from the torn-off areas, the Hungarian refugees who were not protected by anyone, gathered at half-past nine at the Millennium Monument, at the statue of Chief Árpád. The procession started at 9 o'clock, with people from Transylvania in the front, then with people expelled from Upper Hungary and Southern Hungary behind them.

Girls dressed in Hungarian clothes wreathed a statue of Chief Árpád in the Heroes' Square (Source: Képes Krónika, 25 May 1920)

Loud sobbing

The stateless Hungarians marched silently on Andrássy Avenue, under flags, in queues of four, including officials, railwaymen, foresters, wagon dwellers and people living in public accommodation. Women, children, babies, people dressed in uniforms and their own national costumes. Flags and signs were raised high: “The stateless sons and daughters of Transylvania are demanding the return of their peaceful home!”, “Twelve thousand wagon dwellers expelled from their homes are protesting against the peace treaty!”.

"Wagon dweller" family at one of the railway stations in 1920 (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

When they reached the basilica, the bells rang, and all the churches in the capital rang for half an hour. “Hardly any eyes remained dry during the Mass and often loud sobs mingled with the soft psalms,” Az Est reported. After the Mass, after the chanting of Our Lady of the Blessed Virgin and the Hymn, the crowd marched silently on Vilmos Császár Road and Kossuth Lajos Street to march in front of the Petőfi Statue. There was no revelation there either, and the shockingly silent demonstration ended at this venue. According to Pesti Hírlap, the community of the capital expressed its immeasurable grief and sorrow more soulfully than any word and deed during the demonstration.

The Hungarian Territorial Integrity League's protest in Petőfi Square against the signing of the peace treaty (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 23 May 1920)

On that day, the mourners of the lost homeland also gathered in the Egyetem Church, the Kálvin Square Reformed Church, the Deák Square Lutheran Church, and the Hold Street Unitarian Church. They listened to speeches about how the power of the Hungarians would not be broken despite that, and that decision-makers now thank Hungarians with all the evils and sufferings of human hell for defending the borders of Western culture for centuries.

Under the influence of coercion

The National Assembly would also have met on 4 June, but the President, who opened the session, proposed that the meeting not be held because of the peace treaty declaring the partition of the country. Standing from their seats, members of the National Assembly applauded for minutes when President Rakovszky delivered his short speech, which was also published in the Budapest newspapers: “Under the influence of coercion, we sign this so-called peace treaty, but no one can force us to do impossible things. This contract contains both moral and material impossibilities that cannot be realised. All unrighteousness, whether committed upon individuals or nations, will avenge itself, and all injustice will have the profound retribution that it yields an abundant source of good.”

He added: “And to the parts of the country torn from us, we say: After a thousand years of togetherness, we must divorce, but not forever. From this moment on, all our thoughts day and night, all our heartbeats will be focused on uniting with them in old glory, in old greatness, and when we hug them once more to our hearts at the farewell, our hearts will be united so that no violence or power can separate them.”

“A message of war in the form of peace,” the papers quoted a member of parliament as saying about the session of the National Assembly.

Two stateless Szeklers at the protest of the Hungarian Territorial Integrity League (Source: Képes Krónika, 25 May 1920)

"Listen here, peoples of the world!"

On 4 June, the ambassadors of the occupied counties also protested against the decision in Budapest. They gathered in the general assembly hall of the Pest County headquarters. The deputy of Bars County said in a hushed voice that the people of Hungary would never recognise the signed document as a peace treaty.

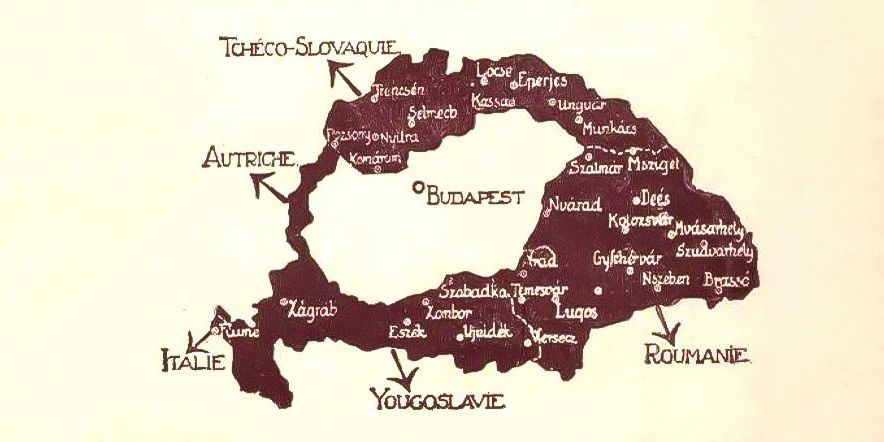

A feldarabolt Magyarország ábrázolása korabeli képeslapon (Forrás: Hungaricana)

Representation of divided Hungary on a contemporary postcard (Source: Hungaricana)

The ambassador of Háromszék County presented to the board the proclamation that they wanted to send to the peoples of the world about the unjust decision made about the Hungarians, and the document was read out at the meeting in Budapest that day. The closing lines of this faithfully express what all Hungarian people felt, thought, believed, and experienced on this day:

„We will fight against the peace forced on Hungary to the last drop of our blood, our last breath. (…) Listen here, peoples of the world: Diminished, though not broken, the Hungarian nation is still alive. They will not be discouraged, they will trust in their ancient power and the living sense of righteousness of Your unspoiled souls, we will solemnly swear to the sacred memory of our ancestors, to the honour of the generation living today and to our descendants, that we will reclaim two-thirds of Hungary, the land that is indisputably ours. At the time of the Hungarian conquest, our leaders took possession of Hungary with a blood treaty a thousand years ago. The blood treaty imposed an obligation on us to keep our country for our descendants, even with blood and iron, unless otherwise possible. We will keep it, God helps us!”

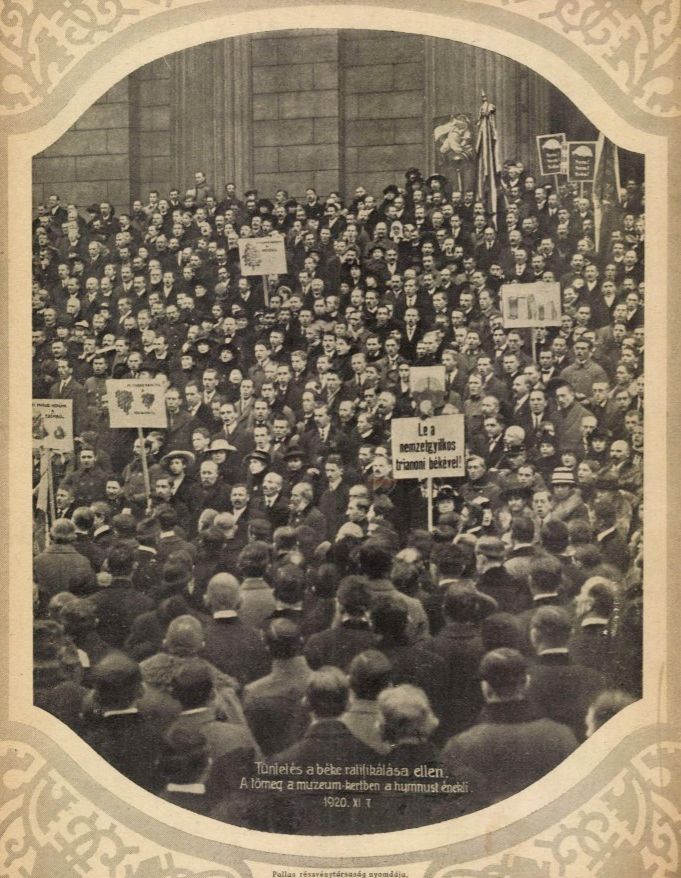

Demonstration of the Hungarian capital against the ratification of the Trianon Treaty. Photos: 1. The area around Vigadó Square while the protest rally was taking place inside. 2. The Association of Awakening Hungarians opens the demonstration procession. 3. Group of the Hungarian Territorial Integrity League with signs indicating the economic resources of the country (Source: Képes Krónika 16 November 1920)

Demonstration against the ratification of the peace treaty. The crowd sings the Hymn in the Museum Garden (Source: Képes Krónika 1920)

Goodbye, our sweet siblings!

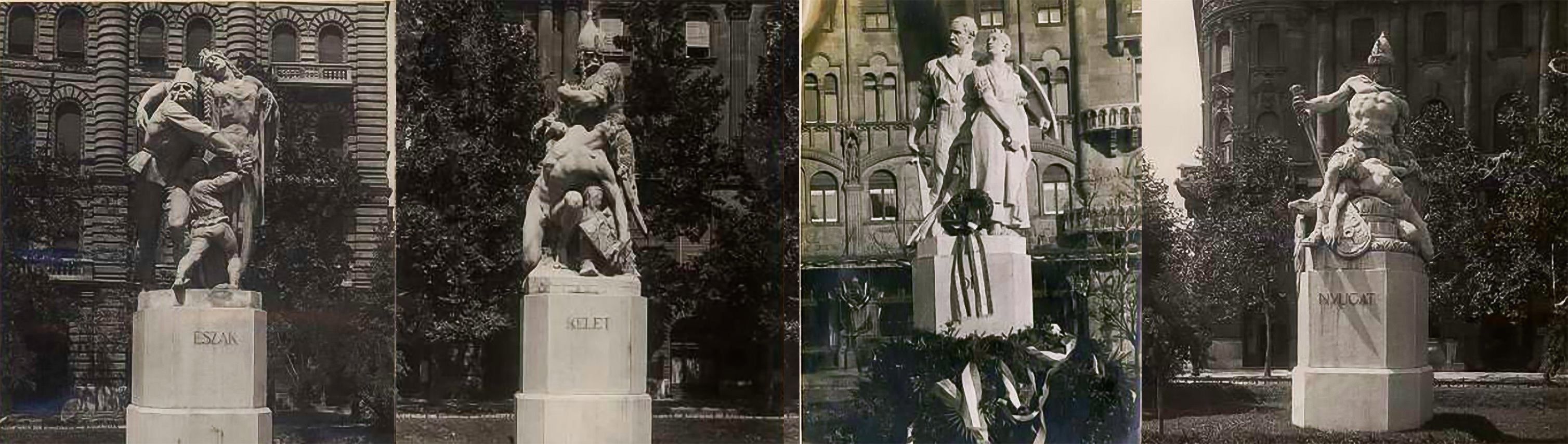

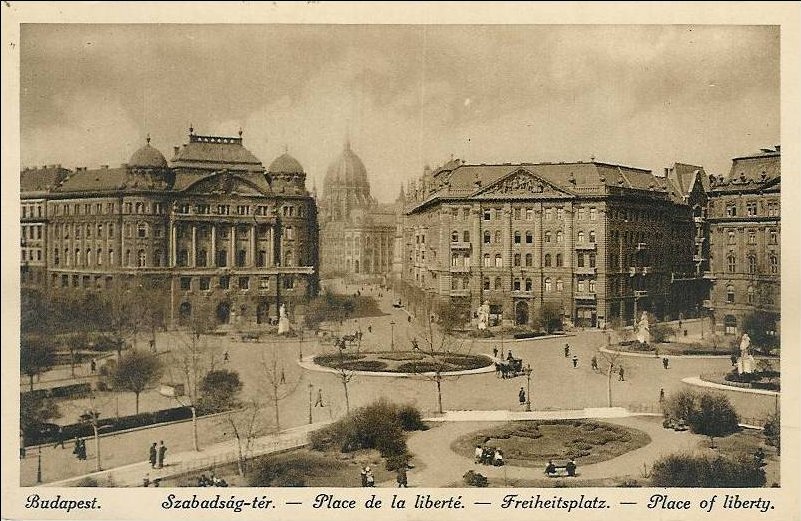

The irredentist statues in Szabadság Square. The North symbolises the loss of the Highlands, the East, which refers to the loss of Transylvania, the South, which expresses the loss of the southern parts, and the West, which reminds of the loss of the western parts of the country. Their creators in the order of the pictures: Zsigmond Kisfaludi Strobl, János Pásztor, István Szentgyörgyi and Ferenc Sidló (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

However, grief and sorrow did not mean acceptance for the people of Budapest either, as the newspapers have clearly and undeniably put it those days. “We will fight and fight against this treaty that has been commanded upon us in our helpless situation,” wrote Az Est.

"The Hungarian nation will always be able to stand before the tribunal of history with a raised head for failing to implement the provisions of this treaty's mock death sentence and seize the first opportunity to cut off the halter strangling his neck," can be read in the Friss Ujság.

In front of the East Statue of the Irredentist Monument in Szabadság Square in 1921 (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

The National Flag of Trianon on half-mast on Szabadság Square (1928-1940). The work of Richard Füredi and Jenő Kismarthy Lechner was inaugurated in 1928 (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

"But as soon as strong plants grow through the prison wall, the vibrant Hungarian race will outgrow the map's prison fence," wrote Pesti Hírlap, which called 4 June the day after the signing the blackest day. They called the events an amputation, the peace treaty a shackle, the decision-makers an enemy, while at the same time mentioning the wealth of adventurers who came to power after the war.

“The primordial strength of the Hungarian nation, which has struggled with the vicissitudes of a thousand years, will also cope with the wild cruelty of the judgment now struck. Suffering will not break this nation, as it has not broken it for thousands of years, even though it had enough of it” can be read in the Magyarország.

Protest against Trianon in Szent Gellért Square in 1929. In the background is the Cave Chapel on the side of Gellért Hill (Photo: Fortepan)

„We did not accept or sign anything! The pen can roar in Paris, the paper can be patient, no heart to beat, no soul to flare, no sense and morality to recognize injustice and stand up against it. But the people of Hungary are not a lifeless corpse that will silently tolerate kicking and lie insensitive in the dust at the feet of the victors. As long as we live, the protest will not die on our lips and the unbreakable belief that the dawn of Easter will come after this darkest Friday when we are resurrected will not perish from our souls.” the Világ wrote.

Szabadság Square, an irredentist memorial site made of flowers, opposite Honvéd Street in 1938 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 100462)

The 8 Órai Ujság summed up the loss of the nation on 5 June, the following day of the signing: “Four million Hungarians, dressed in foreign mockery, look towards the multi-towered Budapest with teary eyes. The Carpathians, the Transylvanian oaks, the black nuggets of Bácska, the arches of Sopron, Rákóczi's ashes in the Košice Cathedral, the Arad ramparts, the willows of Temes are saying goodbye. Goodbye, our sweet siblings, our radiant mountains, our dear plains!”

Szabadság Square on a contemporary postcard with the irredentist sculptures erected in 1921

Cover photo: The protesting crowd in front of the Millennium Memorial (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 23 May 1920)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration