When Miklós Ybl, who was highly respected and recognised by all, died unexpectedly after a short illness at the age of 77, in 1891, a significant work, the expansion of the Royal Palace in Buda was left behind in a barely begun state. Previously, it was self-evident to everyone that this large-scale task could only be performed by the most influential architect, arguably the most talented and hard-working, i.e., Miklós Ybl. But who can come after? Who can follow him? - that was the main question right after his death.

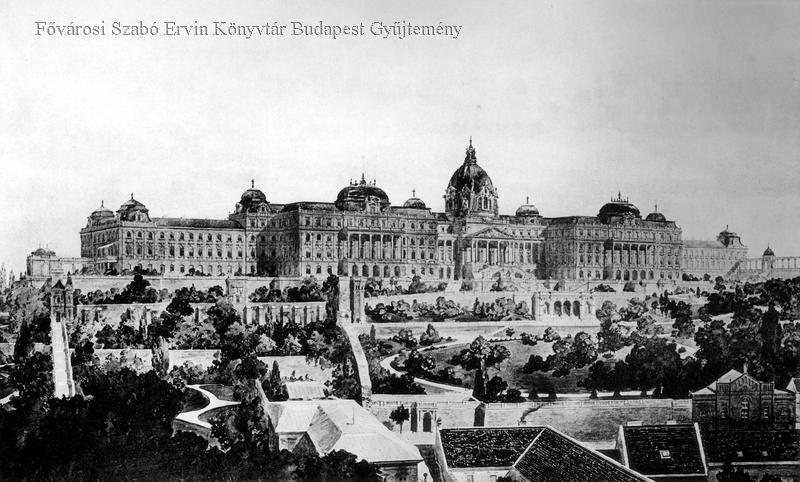

The Royal Palace designed by Alajos Hauszmann (now Buda Castle) from the Danube in 1935 (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

Rank and admiration

That this may have arisen as a real dilemma is perfectly illustrated by the bright celebration organised by his colleagues and students for the 50th architectural anniversary of Miklós Ybl in 1882. The ornate halls of the Pesti Vigadó were filled with ministers, state secretaries, members of parliament, museum directors, university rectors, writers, artists, and the cream of the contemporary intelligentsia, Prime Minister Kálmán Tisza could not go only because of his illness.

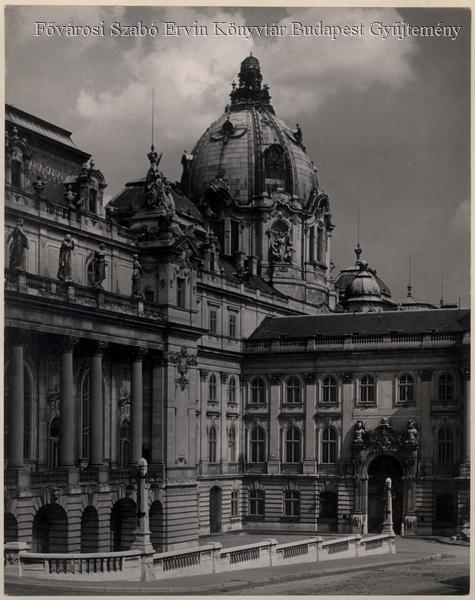

The western facade of the Royal Palace, the Krisztinaváros wing in 1900. Miklós Ybl designed this wing, but due to his death it was built by Alajos Hauszmann - transformed according to his idea (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

Yet not the large number of counts and members of the upper house present showed the real esteem and recognition of Miklós Ybl, but the almost touching offerings that the capital company supplied the gas to the lamps for free that day for the evening lighting of the ceremony in his honour. And, of course, it is rare for a statue to be erected in someone’s life, as in that evening in Pesti Vigadó, when the bust of the master was inaugurated in the building as part of a lavish ceremony.

His unquestionable authority is shown by the fact that the king ordered him to Vienna in 1883 to negotiate with him for the expansion of the palace. And when Franz Joseph arrived on the evening of 27 September 1884 for the opening ceremony and performance of the then completed Opera House, it was natural that the designer Miklós Ybl would receive the king in the company of the Prime Minister. The excellent relationship between the monarch and the architect was shown by the fact that Franz Joseph, as an old acquaintance, shook hands with Ybl and inquired about his state of health, while greeting the others, including the members of the construction committee, only according to the usual protocol.

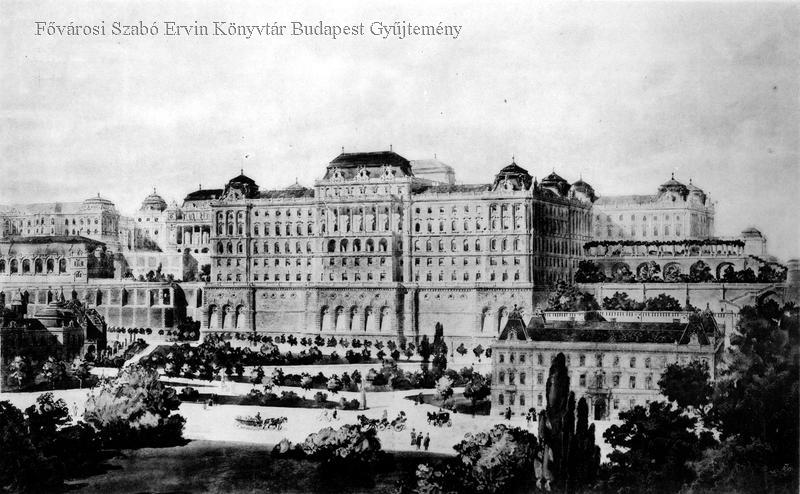

The royal palace from the Danube according to the plan of Miklós Ybl. This solution did not materialise (Source: Az Építési Ipar, 1886, Volume 10, No. 1/470-52/521)

This rank and admiration should have somehow been reached by the one who gains the opportunity to design and build the palace further. But there was another important aspect here. Ybl died in the upward era of the development of national self-consciousness when the country was built with great hope, self-confidence, and enthusiasm, not only out of stone and mortar but out of soul and national will, that is, in a real and symbolic sense.

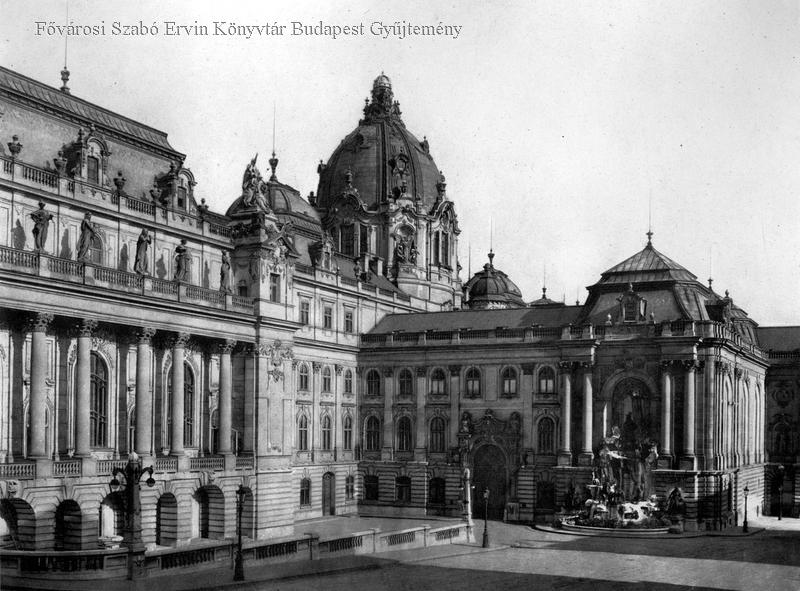

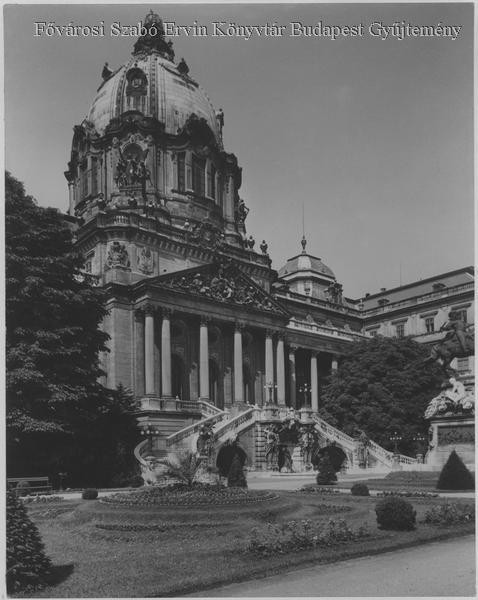

The central part of the royal palace built by Alajos Hauszmann with the dome, photographed from the Hunyadi Courtyard, the new festive hall on the left, and the Mátyás Well on the right, in 1912 (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

Budapest was the driving force behind this enthusiasm and an example for other cities. The new designer of the palace had to be a personality who was able to represent the national idea and Hungarian interests, and with their rank, within the architectural society, they could maintain the confidence of architects and builders in the future.

Chance of a lifetime

At the time of Ybl’s death, barely 24 years had passed since the Compromise. The cosmopolitan city of Budapest was nascent, Andrássy Avenue was already decorated with several palaces. The Opera House and St. Stephen's Basilica were completed, and the ornate houses grew out of the ground one after the other on the designated trail of the Outer Ring Road. The Parliament was under construction in Tömő Square, countless magnificent buildings adorned the centre of the nation, and the work nurtured several talented generations of architects. Yet: in January 1891, no one would have dared to state definitively who was the most deserving official to continue the task that had been interrupted by the death of the great master.

The main gate of the royal palace in 1900, without the lions. To the left is the window of the royal chapel, beyond the gate is the Lion's Court (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

At the same time, the death of the influential predecessor appeared in the imagination of many as a never-returning great opportunity in their lives, because let us think about it: who would not want to read in their biography an item that says that the design and construction of the country’s number one building, the royal palace, is connected to their name? No wonder, then, that many people began to look for connections to win the job. Someone tried at the Prime Minister's staff, someone at the Public Works Council, or its leader, Frigyes Podmaniczky, someone at the Buda Castle Construction Committee, or even the majordomo.

The eastern facade of the royal palace facing the Danube, designed by Alajos Hauszmann in 1900 (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

We will never know how many architects had in their imagination the idea that they could be the designer of the royal residence in Buda, but some names can be found in the diary of Alajos Hauszmann. According to his information, the list included Gyula Bukovics, Ödön Lechner, Gusztáv Petschacher, Gyula Pártos, Henrik Schmal, among others, but it will remain obscure forever who else is to be understood at the end of the list under "etc.".

Under such circumstances, architect Alajos Hauszmann was visited at the beginning of 1891 by Sándor Országh, one of the most prestigious experts in Budapest, which was growing into a modern world city. Although he was a Member of Parliament, he did not arrive in this capacity, but rather as the head of the department of the influential Public Works Council and the rapporteur of the construction committee of the Royal Palace. The renowned urban planner, who had already written a book on Budapest's public constructions, told the much-respected professor at the Technical University that the recently deceased Miklós Ybl, who left the great legacy of building the royal palace behind, once explained that he would only entrust Hauszmann with the continuation of his buildings.

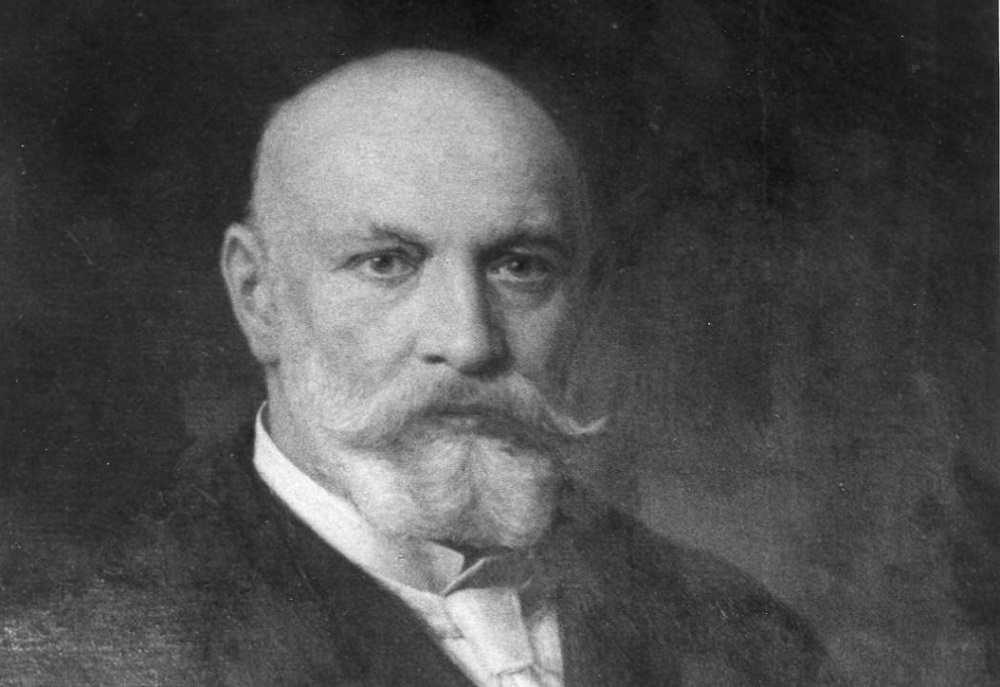

Portrait of Alajos Hauszmann (Forrás: omikk.bme.hu)

Alajos Hauszmann himself, as it can be read in his diary, attributes to this Ybl remark that instead of many volunteers, he was eventually given the most prestigious mandate in the country. Frigyes Podmaniczky, chairman of the construction committee, with the committee's unanimous consent, nominated him to the prime minister as Ybl's successor.

Although the already mentioned Sándor Országh told Hauszmann this in advance, who did not tell anyone about it, he even kept it a secret from his family. He waited quietly and wisely for the decision.

The central part of the eastern facade of the royal palace facing the Danube with the Habsburg staircase in the 1920s (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

By this time, he had designed countless buildings in the Carpathian Basin: residential houses, churches, castles, schools, hospitals, banks, university buildings, the courthouse, and taught at the Technical University for 23 years, thus, he taught a significant part of the designers who were involved in the construction of the world city.

Miklós Ybl saw the opportunity in him, but the recognition was mutual: Hauszmann called his predecessor an excellent man, one of the pioneering architects of the country, who also stood out with his sincere character and kindness - his opinion can also be read in his diary.

The old ceremonial hall in the Maria Theresa wing was remodelled and enlarged in 1912 (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

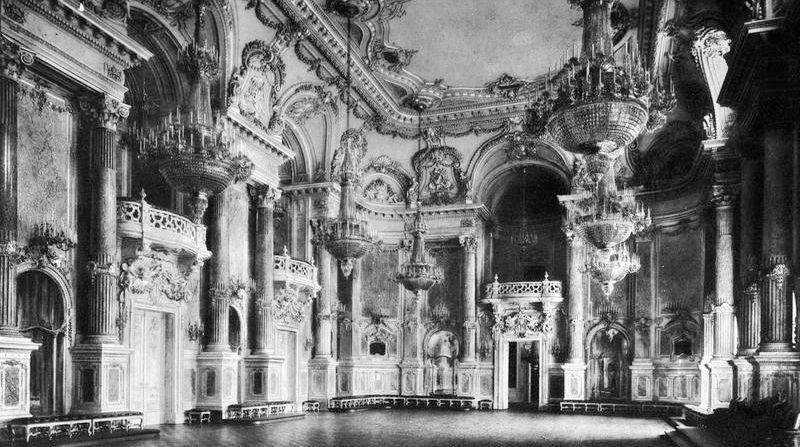

The ballroom of the Royal Palace in the wing designed by Alajos Hauszmann, in 1926 (Photo: Hungaricana/Csiky Fotó)

The buffet gallery on the side overlooking the Danube in the newly built wing, in 1912 (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

Ground floor foyer in 1912 (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

Royal commission

In accordance with the unusual oral will, in the end, indeed, Alajos Hauszmann won the commission.

Miklós Ybl's funeral was in January 1891, and Hauszmann received the Prime Minister's note in March that "His Majesty, Franz Joseph, had appointed him the construction manager of the Royal Castle." His first trip in this capacity led to the Prime Minister, Gyula Szapáry, to whom he went to an audience to discuss the tasks.

This was a critical period in the design of the palace, as the heir to the throne, Rudolf died two years earlier, so many were of the view that this tragic event made it necessary to rethink whether construction was necessary at all, as the new Krisztinaváros wing, whose plans were made by Ybl, would have been built for the heir to the throne. This was also discussed during the meeting with the Prime Minister.

Dining room in the Archduke Suite in 1912 (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

However, this did not end the line of audiences for Hauszmann, as he also had to visit the majordomo, Prince Hohenlohe, who greeted him with these words: “I am glad I just get to know you now and that you did not try to ask for my influence like many of your colleagues.” - it can be read in Hauszmann’s recollections.

Hauszmann then met the king himself, and when he thanked him for the commission, Franz Joseph replied that he would entrust him with complete reassurance to build the royal castle because he had given enough proof of his talent so far. The king also explained that he was sure he would do this work to his satisfaction as well.

Alajos Hauszmann had a ceremonial hall built in the palace for our two great rulers, St. Stephen, and Matthias. The picture shows the King Matthias Hall in 1912 (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

At that time, Alajos Hauszmann could not yet know what he was committing himself to, nor did he even remember that he had committed himself for almost 15 years that day. This is how much time it took to design, build, decorate, and furnish the royal palace in Buda.

There could not have been a better professional found for the job. Step by step, with excellent diplomatic sense and great negotiation techniques, he enforced the best interests of Hungary during the construction of the royal palace, and he was also able to realise his wide-ranging ideas despite his struggles with the court chamber. Namely, in such a way that Hungarian artists received special and unique assignments when decorating the palace, thus developing the entire Hungarian art life.

Alajos Hauszmann was able to enforce Hungarian interests, so the Holy Crown could be placed on top of the dome. (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

After the Compromise of 1867, newspaper articles dreaming about the expansion of the palace said that the Hungarians thought back with nostalgia about King Matthias's time, the then bright Buda Palace, and secretly hoped that the old glory could return one day. Alajos Hauszmann fulfilled the nation's dream: he managed to build one of the most beautiful royal palaces in Europe. The beautiful masterpiece was marvelled by the world, just as it was in the Middle Ages when the saying went: Around Europe, there are three admirable cities: Venice on the waters, Buda on the hills, Florence on the plains.

Cover photo: Ballroom of the Royal Palace in the wing designed by Alajos Hauszmann in 1912 (Photo: Budapest Collection of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration