Until the 1850s customs cases in Budapest were handled by the Imperial and Royal Thirtieth Customs offices. These were in a building that stood on the present-day Vörösmarty Square, near what is now the Gerbeaud House. The plan to move the customs offices to a new location better fitting their increased needs was first floated in the 1830s. The resulted in prolonged negotiations between the city and the financial authorities.

Finally, in 1846 Tömő Square (present-day Kossuth Square) was chosen as the location for the new building. The revolution and war of independence and the years of repression that followed sidelined the issue for years. In 1867 the question was raised again within the Hungarian Ministry of Finance. Menyhért Lónyay, the minister at the time, was connected the old plans, and in 1869 commissioned Miklós Ybl to design a palace for the customs offices (on the site that would become the Ministry of Agriculture).

This rapidly growing part of Lipótváros, popular among wholesalers and craftsmen indeed seemed like the perfect spot for the customs house. Lónyay believed that it would be more practical to handle clearance in the centre of the city than in some outlying area. However, it soon turned out that the minister had not aligned with the City Council, his fellow ministers, or even his boss, Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy.

Portrait of Count Gyula Andrássy in the 14 March 1867 issue of Hazánk s Külföld

Portrait of Menyhért Lónyay in the 14 March 1867 issue of Hazánk s Külföld

The Ministry of Finance announced a tender for the construction of the palace at the beginning of 1870, which was one by Ignáv Wechselmann with an offer of 1,050,000 Forints. Work began immediately. Miklós Ybl, as the lead architect then appeared before the Pest Construction Committee to request that the nearby riverbank be regulated as quickly as possible.

Only then did the city council even learn of the construction. It seemed that there was no going back, but the Committee launched a counter-offensive. They attempted to convince Menyhért Lónyay to chose a new location several times through March but in vain.

Finally, 20 April 1870 the pest City Council turned to the Prime Minister protesting the construction. Their letter stated that the customs house, and public warehouses that would be needed alongside it, would hinder the development of Lipótváros, as both would have to be connected to Pest Railway Station (the predecessor of the present-day Nyugati Pályaudvar). These tracks would then adversely affect the planned development of the Large Ring Road and further urban development.

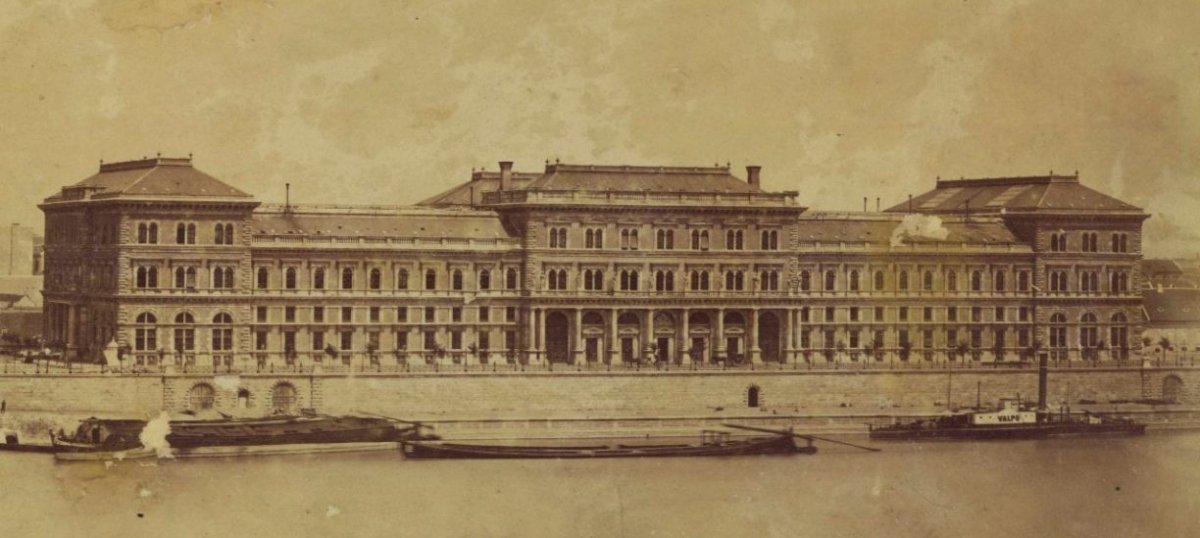

The Main Customs House

Andrássy, surprised by the events, agreed with the city administration. He believed that the palace should be beyond what is today the inner ring road. Nevertheless, Lónyay objected that the city had bought the plot years ago for the palace and thus, in principle, approved the construction.

ÍHis main argument was that changing the location would result in a massive increase in the cost of the project. He also added that foundation work was well underway. Nevertheless, Andrássy remained adamant and recommended that the building be built on the border of the inner city and Ferencváros, on Só Square, on the riverbank.

The question was decided, regardless of Lónyay's continued arguments. The Minister of Finance had not only provoked the Prime Minister's anger, but lost a great deal of influence after the events, and was also barred from further negotiations regarding the customs house.

A potrait of Károly Gerlóczy in the 12 September 1886 issue of Vasárnapi Újság

The City Council supported Andrássy's proposal despite the fact that clearing Só Square generated a great deal of expenditure for the city as well. Filling Molnár Lake, which swelled and ebbed with the tide of the Danube, for example, cost ninety-three-thousand Forints.

However, the proximity of the Southern Connecting Railway Bridge already being planned at the time, and the idea of a freight station to be built on the banks of the Danube in Ferencváros, promised the creation of a southern logistics hubs, which allowed goods and raw materials to flow through the city seamlessly, including customs handling.

Visual by Albert Schickedanz in the 30 July 1871 issue of Vasárnapi Újság. The interesting thing about the woodcut is that by the time construction was completed. The artist had designed a road bridge and at least one other significant public building in the vicinity of the Main Customs House.

The original plans for the building would have encompassed what is today the Great Market Hall. However, buying the four private houses on the plot would have further increased the already extreme additional costs. The City Council requested that Miklós Ybl draw an, even more, cost-efficient plan (meaning the architect was forced to redesign the building for the second time).

Once all stakeholders had accepted Ybl's plans, construction finally began on 4 July 1870. The building was completed in May 1874 and cost 3,250,000 Forints.

Potrait of Miklós Ybl in 15 October 1865 issue of Magyarország és a Nagyvilág The Main Customs House photographed by György Klösz around 1900 (Photo: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference Nop.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.019)

The Main Customs House photographed by György Klösz around 1900 (Photo: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference Nop.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.019) The southern facade of the Main Customs House photograph by György Klösz, around 1900 (Foto Fortepan/Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.021)

The southern facade of the Main Customs House photograph by György Klösz, around 1900 (Foto Fortepan/Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.021)

The iron supports of the roof were made by the Schick Foundry based on plans by János Feketeházy. Gyula Jungfer designed the iron ornaments of the staircase. The interior walls were painted by Róbert Scholz, while Márk Róth handled the glazing works. Three inner courtyards ease movement through the 170-meter-long and 56-meter-wide Neo-Renaissance palace. At its completion, the building contained over 300 offices and 100 rooms to provide accommodation for senior customs officers of foreign specialists and guests.

Goods to be cleared could also enter the building by rail as tracks entered the ground floor from the south. The building was built on top of a 4 foot, three-inch-thick concrete foundation to ensure it remained water-tight. The basement, included the boiler-room, the laundry room and the wood-cellars, alongside warehouses which could be accessed from the Danube through four tunnels, which were closed with locks in case of high water levels.

The Main Customs House from the lower embankment, with the tunnel entrances (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.07.128)

The Main Customs House from the lower embankment, with the tunnel entrances (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.07.128)

The 26 ornamental sculptures on the façade – which symbolise the judiciary, legislature, power, the railway, the steamboat, certain branches of agriculture and industry, as well as typical Hungarian crafts – were created by the German sculptor Ágost Sommer.

The Danube-facing façade of the Main Customs House photographed by György Klösz around 1900 (Photo: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.020)

The Danube-facing façade of the Main Customs House photographed by György Klösz around 1900 (Photo: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.020)

Sculptures by Ágost Sommer on the balcony facing the Danube, around 1960 (Photo: Ferencváros Local History Collection)

Both magazines and publications on popular science praised the elegance of the Main Customs House (or Palace) and its harmony of beauty and practicality. A few voices did question why the budget of the project had tripled, but these faded quickly – and nearly no one remembered the debates that had raged around the building before its construction.

Cover photo: View of the Main Customs House from Buda around 1875 (Source: Budapest Archives, photo albums by György Klösz)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration