Most artists are much more active during their lifetimes then what posterity remembers of them. Born in 1864 Imer Francsek, the elder is one of these architects. Following the Technical University, he worked in the office of Győző Czigler and Ferenc Pfaff. Later he became an engineer at the Budapest public works Committee and judged several design tenders as a member of Magyar Mérnök és Építész Egylet ('society of Hungarian engineers and architects'). He entered several tenders himself, published several articles and gave lectures.

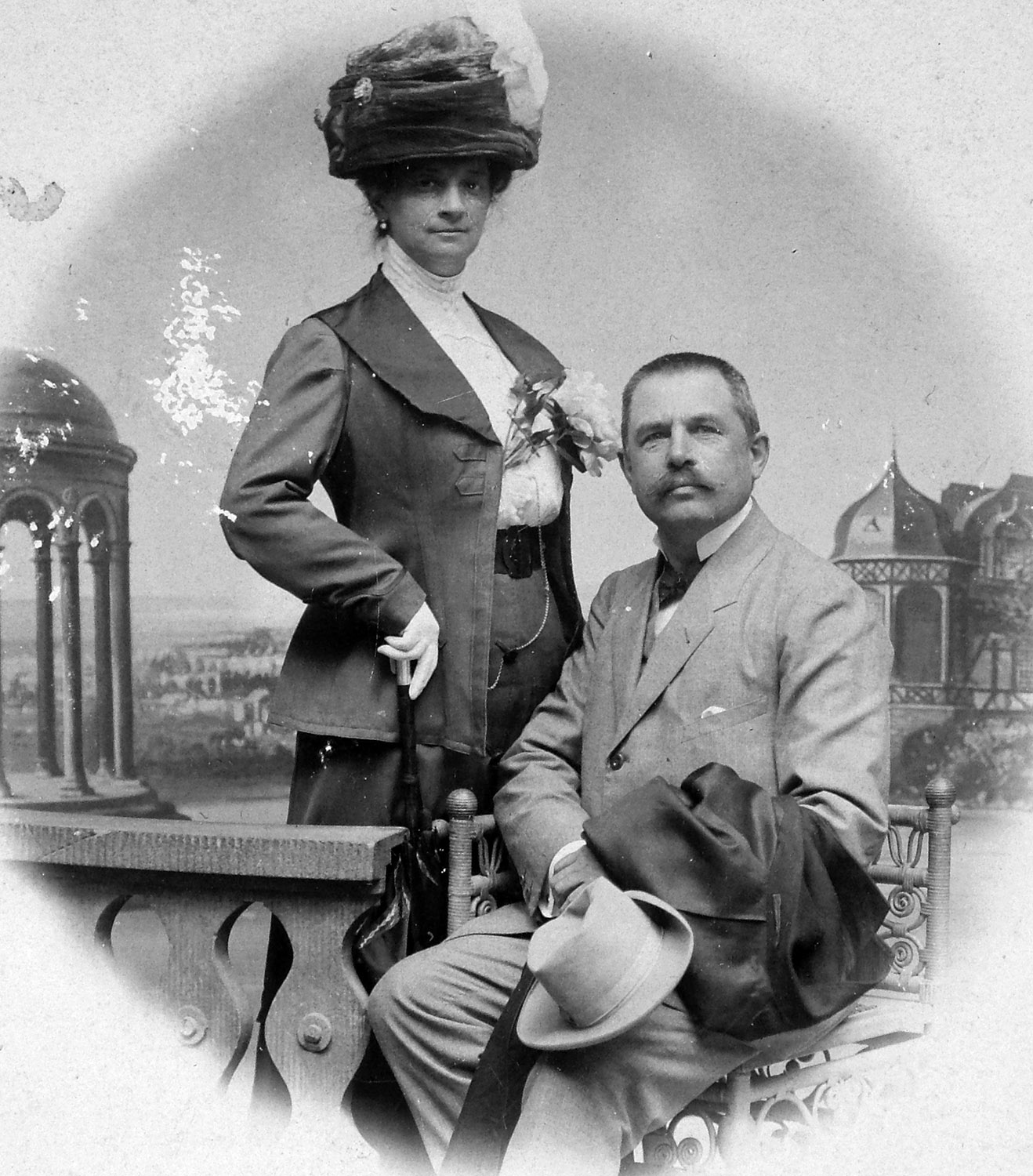

Imre Francsek the elder and his wife, Eleonóra Sacher around 1910 (Source: Fortepan/No.: 14673)

For example, he once wrote that Ignác Alpár – the designer of the Budapest Stock Exchange, later the headquarters of the national television service – had contacted him for advice, when the Public Works Committee blocked construction of the building's central avant-corps. In a letter published in the periodical of the society (10 December 1905), Francsek noted that despite Alpár's flattering claim it was not due to his intervention that the emblematic element of the building could be built.

His contemporaries knew him well, but what does posterity know of him?

When designing the building for the City Park Ice Skating Rink, Francsek considered the characteristics of the previous buildings, which had been planned by Ödön Lechner (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

When designing the building for the City Park Ice Skating Rink, Francsek considered the characteristics of the previous buildings, which had been planned by Ödön Lechner (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The original skating rink designed by Ödön Lechner photographed before 1896 by György Klösz (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

His most well-known work in Budapest is the City Park Ice Skating Rink. The neo-baroque building was completed towards the end of 1893 after only six months. Francsek treated the earlier building, which had been designed by Ödön Lechner with a great deal of respect. The three-part design and avant-corps of the building are essentially a rethinking of Lechner's plans. Naturally, the new building was much bigger. It was equipped with everything that the previous building had lacked, when

"our mothers and fathers tied the rudimentary, hook-nosed, wooden-skates to their feet,"

as written in the 3 February 1895 issue of Vasárnapi Ujság. The building included heated, spacious dressing rooms, lockers, cloakrooms, a skate rental, a dining room and even space for an orchestra.

The building stretches 150 metres alongside the skating rink (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The colonnade of the Saint Gerard statue

One of the most photographed points in Budapest, Gellért Hill is also adorned with work by Francsek. The architect designed the colonnade that surrounds the statue of Saint Gerard (by Gyula Jankovits), the architectural elements of the statue and the fence that runs along the base of the hill. While Mór Kallina is often cited as the architect behind the colonnade, Kallina only won the design tender for the landscaping of the area, through his joint entry with Aladár Árkay. The final implementation. However, the Public Works Committee entrusted its architect, Francsek with the final implementation, most likely due to economic considerations.

The colonnade designed by Francsek (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

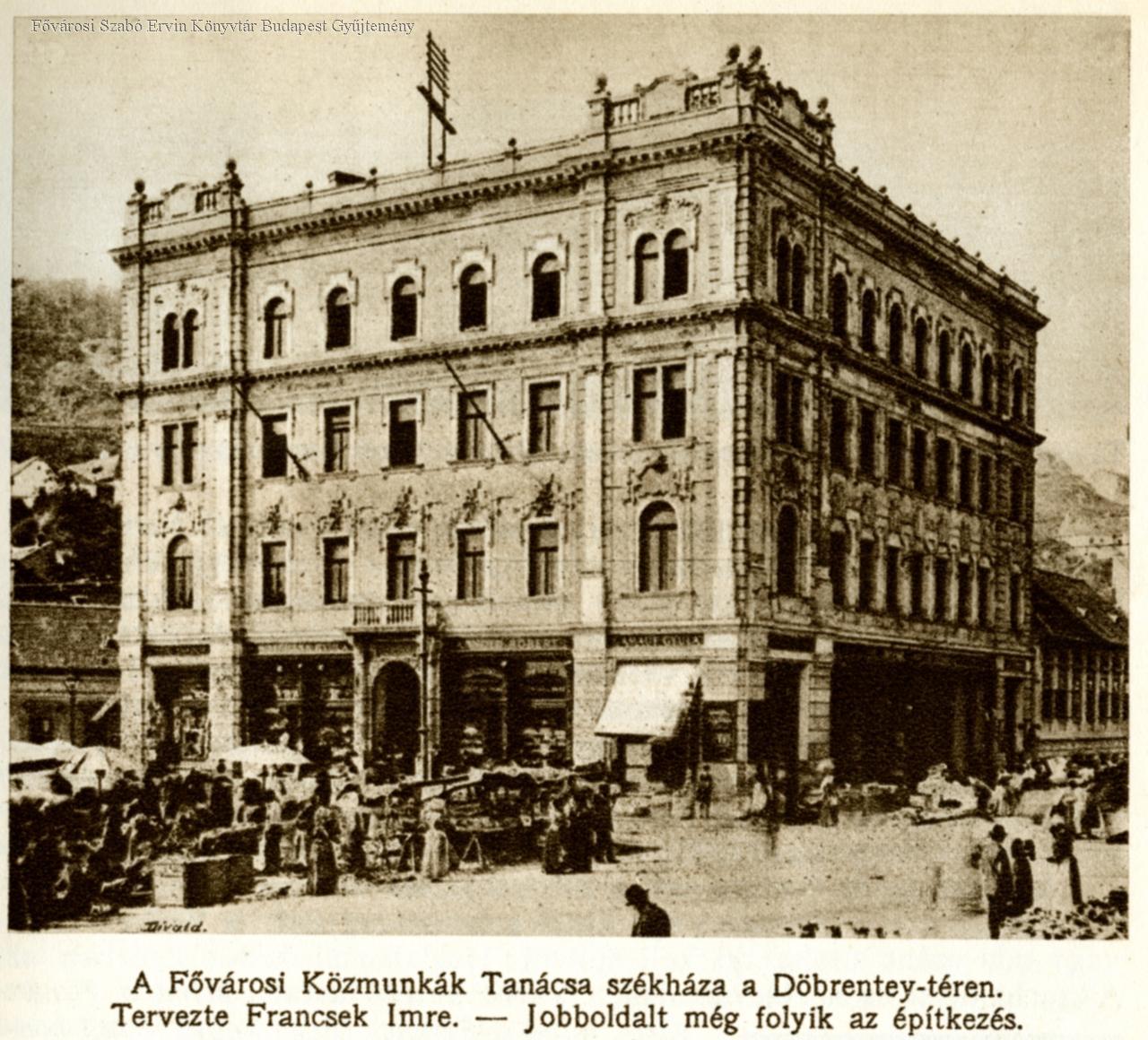

Former headquarters of the Budapest Public Works Committee on Döbrentei Square

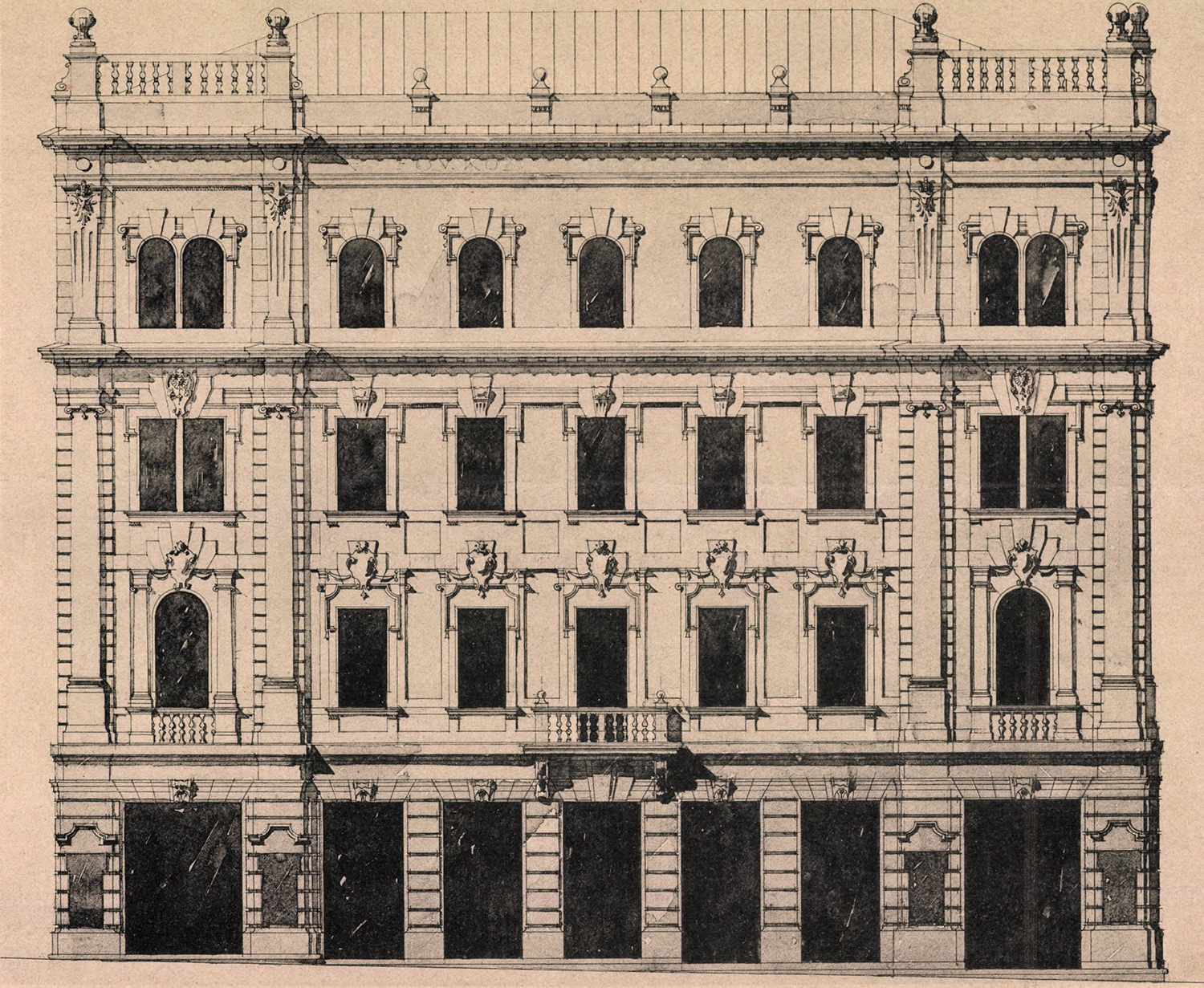

The Public Work Committee commissioned Francsek to design its new building at 4 Döbrentei Square. The architect himself announced this in the 20 January 18ö7 issue of Építő Ipar, adding that János Baka was supervising his planning and utility work.

Plans for the headquarters of the Budapest Public Works Committee in the 27 January 1897 issue of Építő Ipar

The article details that shops were created on the ground floor section of the building which faced the two squares. The area facing the side street contained a flat for the doorman, the main staircase, and a flat for a servant. The first floor was dominated by a "meeting room of the size required by the council, a spacious foyer alongside offices for the president, the support staff and the archives. The second floor houses the technical and financial departments. The third floor is currently offered as rental housing, to recuperate the costs of the construction but can be converted easily into more offices should the tasks and responsibilities of the Committee be increased."

The almost complete building photographed by Károly Divald (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The almost complete building photographed by Károly Divald (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The article also notes that the roof of the building was complete and plans were to finish it by August. Not much later the Committee moved into the building. However, in 1938 it was moved into the new red-brick building on Madách Square, and the house was demolished.

A legendary building on Krisztina Square to be revitalised as a cultural centre

The renovation of the Buda Civic Casino at 1 Krisztina Square was announced recently. One of Francsek's most beautiful works (1893), the building was heavily damaged in World War 2, its tower and much of its decorations destroyed. The major architectural elements of the building will be restored (for example the corner dome) as a result of the current rebuilding, as will many provable ornaments. However, the facade will generally be more straightforward than the original design. The representative main hall on the first floor and the main staircase are also being restored. The courtyard is being roofed to provide more space for the Márai Sándor Cultural Centre, which will move into the building.

The Buda Civic Casino shortly after completion and today under reconstruction (Photos: Építő Ipar 28 December 1893 and Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

From the beginning of the 1900s to the middle of the 1910s the ground floor of the building, currently a supermarket, housed the legendary August Confectionery, the site of romantic meetings. Several magazines and newspapers of the day are filled with ads in which men (and sometimes women) hoped to meet their chosen at the indicated time, even in secret. As one of the authors of an ad in the 23 October 1910 issue of Budapesti Hírlap wrote:

"My letter is sent. Meet me today, incognito, in the August confectionery on Krisztina Square (at five). My regards."

Offering a glimpse behind the scenes of matchmaking before phones and the internet.

The main hall of the Buda Civil Casino in the 28 December 1893 issue of Építő Ipar

A technological marvel – How do you move a house?

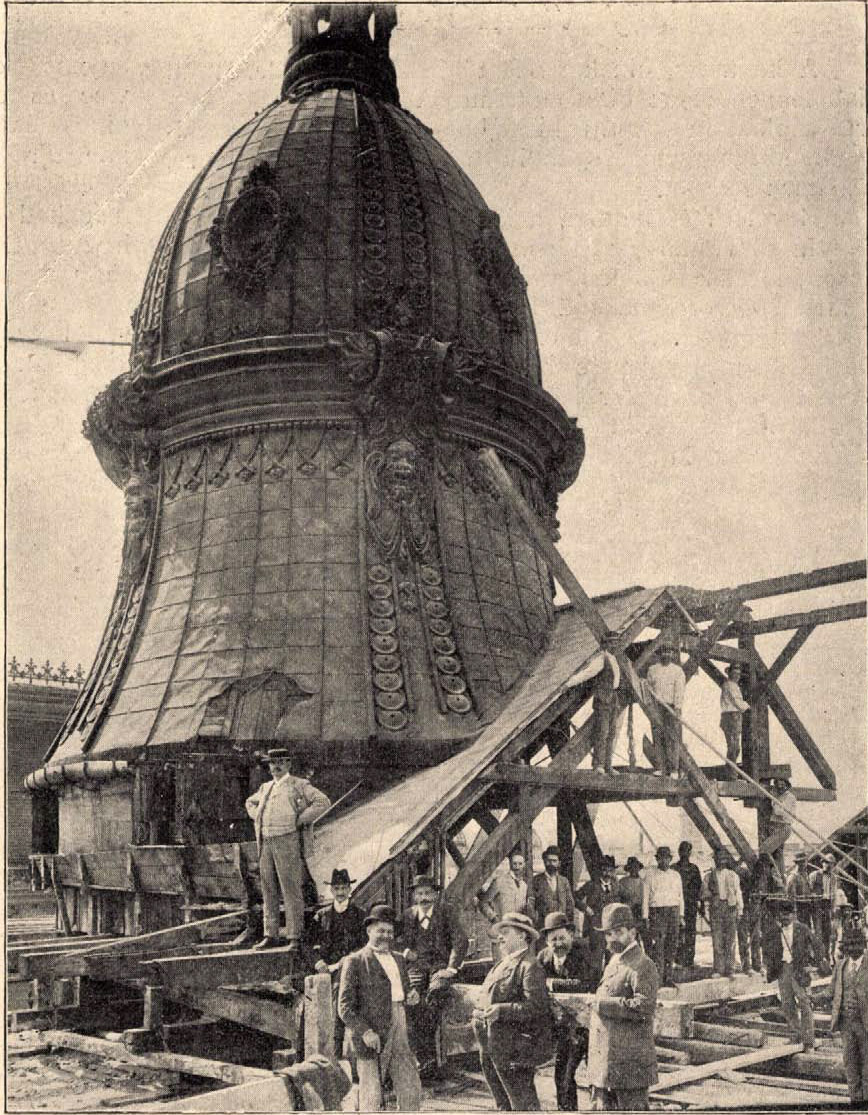

In 1899 the architect was given an exciting task. He had to move the dome of the Dreher Palace on the corner of Kossuth Lajos Street and Városház (then, Gránátos) Street. Kossuth Street was to be widened because of the construction of the Eskü Square (today Erzsébet) bridge. As the influential Dreher family did not even consider demolishing its recently constructed palace, a different solution had to be found.

György Klösz's 1894 photograph shows how far the domed Dreher Palace protruded into Kossuth Lajos Street. The idea of moving it was no accident (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The Műszaki Hetilap ('technical weekly') published a detailed report of the operation. Imre Francsek had initially planned to push the whole building back, relying on technology already sued in the United States (the same idea was floated regarding the Inner City Parish Church nearby). Eventually, only the dome was moved. The operation began on 4 august 1899 and lasted four days. The 30-tonne structure was raised with tracks and iron bars, and slowly pushed 20 metres away. Later the section of the facade that protruded into the street was torn down and rebuilt several meters away. The dome was finally moved into its new place. In a unique twist of fate, while the palace is still standing, the dome was torn down after World War II.

The dome of the palace while being moved (Photo: Uj Idők, 13 August 1899)

Residential Buildings: Woven into the fabric of the city

Francsek also designed several residential buildings. The most impressive of these stands at 11 Rákóczi Road, which was built in 1900 for Egyesült Fővárosi Takarékpénztár ('united Budapest savings bank'). The massive building surrounds two internal courtyards. The ground floor towards Rákóczi Road housed shops and the local branch of the bank. Flats were created facing Puskin Street. Five street-facing and three courtyard-view flats were created on each floor. Imre Francsek and his family lived in the building, which also had two electric lifts.

Imre francsek and family lived in the residential building under 11 Rákóczi Road (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

He designed the eclectic house under 51 Szentkirályi Street and the corner house of the Evangelical Church at 24 Üllői Road. The building completed in 1906 was the administrative centre of the church, including its archives and library, flats and even a church on the first floor. The building is still used by the Church and was recently renovated, with work finished in 2017.

51 Szentkirályi Street was renovated a few years ago (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

In a strange coincidence, Francsek planned several corner houses, 17 Damjanich Street is another. The original two-storey house was expanded with two new floors after the second world was, resulting in a rather grotesque overall effect. The situation has changed slightly following recent renovations but remains strange as a whole. The bold pink and orange colour scheme also emphasises the building in the grey view of the street.

17 Damjanich Street was originally a two-storey building; the upper two levels were added later (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

17 Damjanich Street was originally a two-storey building; the upper two levels were added later (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Since 2015 a memorial plaque has informed passers-by that the literary historian Ágnes Gereben was born in the house

Redesigned Square – Szabadság Square and Calvin Square

Imre Francsek also entered several design tenders. He won a competition announced for the landscaping of the area the Újépület ('new building') where Lajos Batthyány – the first prime minister of Hungary was imprisoned and executed. The massive building which occupied the entirety of what is today Szabadság Square was torn down in 1897, and the area had to be redesigned, mainly due to the proximity of the Parliament already under construction. The final implementation happened according to plans by Antal Palóczi.

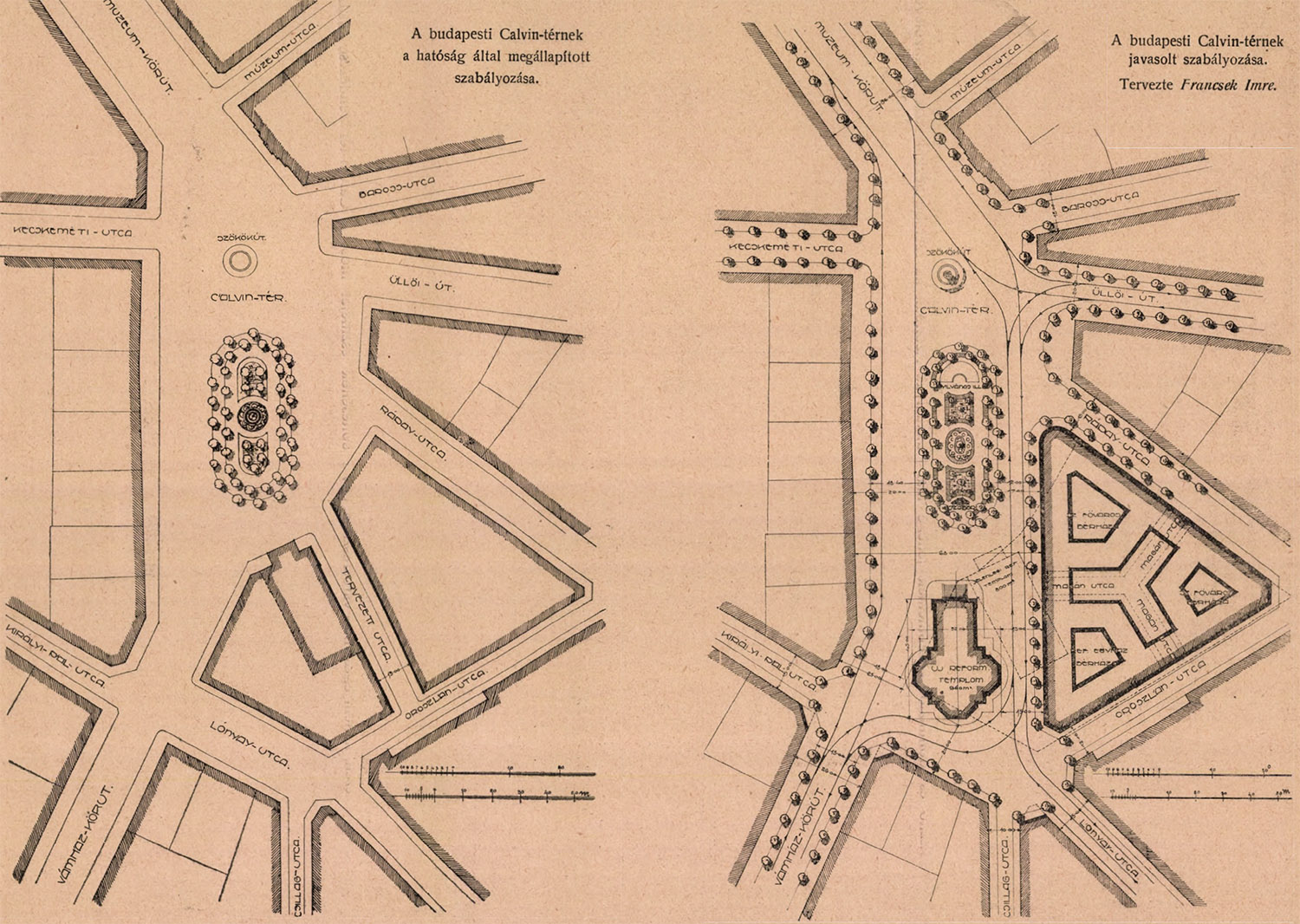

The official plans (left) for Kálvin Square (formerly Calvin Sure in Hungarian as well) shows a solution similar to the present day. On the right, the solution proposed by Francsek. The architect would have torn down the reformed church and created a building twice the size in the middle of the space (Source: Építő Ipar, 20 April 1913)

Calvin Squar would also be completely different if the capital and the Reformed Church in Hungary would have implemented the plans Francsek laid out in 1911. The architect argued that the square should be rearranged entirely and straightened. His plans included the demolition of the small houses and church on the southern side of the square. These would have been replaced by residential buildings. The church would have been mode to the western side of the square and doubled in size. The plan was never carried out, and the church designed by Vince Hild still stands.

Two architects with the name Imre Francsek have graced Budapest. While the younger is remembered for his expansion of the Széchenyi Baths in 1927, the elder planned buildings that are part of the very fabric of Budapest. The elder Francsek never saw his son's major work come to life, as he died in 1920, aged only 55.

While Imre Francsek the elder is not considered a leading Hungarian architect, he was respected and well known in his time, and designed buildings, without which, Budapest would not be the same.

And of course, he was a pioneer in something. So the next time you hear of a dome being moved, remember that a Hungarian architect completed a similar feat almost 100 years ago.

Cover Photo: The building of the City Park Ice Skating rink (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration