Royal Hungarian Mental Asylum (later OPNI)

The issue of opening an asylum in Hungary was first raised in 1791. The idea remained just that, however, until Hungarian patients were barred from the mental hospitals in Vienna, Prague and Lemberg by decree. The view was that as there was no similar institution in Hungary, the country was unable to return the favour. During the Reform Period of the National Awakening, the question was raised again. At the beginning of 1848, the Governor's Council sent Ferenc Schwartzer (who had previously worked in the mental department of the hospital in Vienna) on a state-funded tour of European mental asylums.

Schwartzer visited mental hospitals in England, France, Belgium and German-speaking territories and submitted a proposal for the creation of a Hungarian mental hospital to the Hungarian government in the autumn of 1848. Implementation was hampered by the 1848–49 war of independence, during which Ferenc Schwartzer returned to Hungar and served as surgeon-major under Richárd Guyon. Following the Surrender at Világos, the doctor emigrated. He returned to Hungary in 1850 and founded a private mental hospital, which he moved to Buda in 1952.

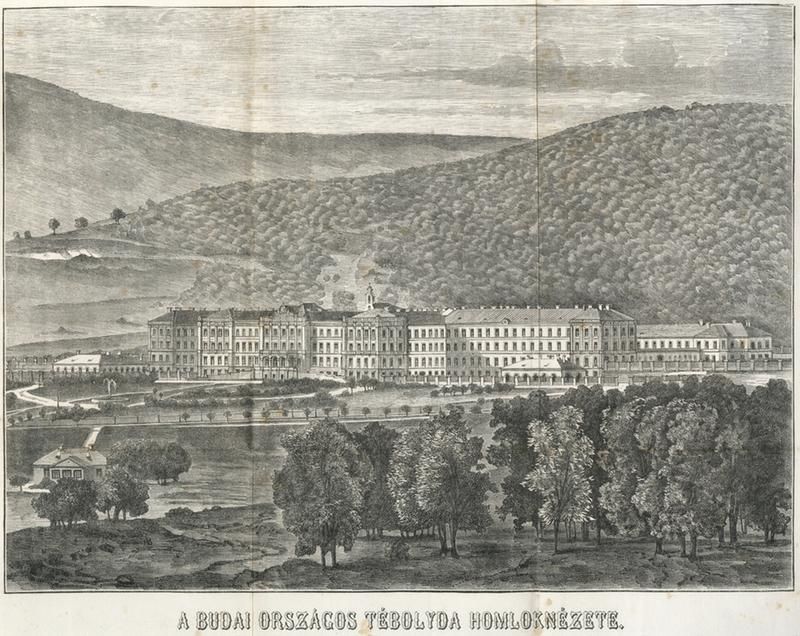

Drawing of the Royal Hungarian Mental Asylum from 1869 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

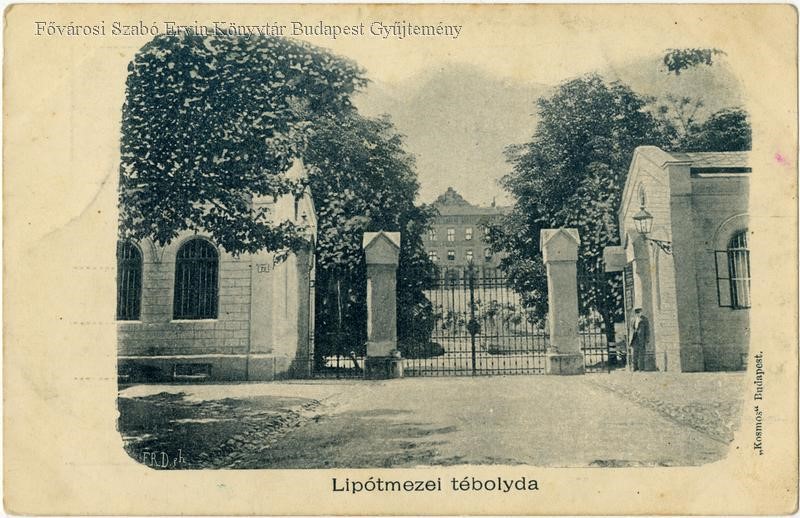

The government had not forgotten the issue either, and in the 1850s the issue became vitally urgent. This led to the purchase of a plot of land in Hűvösvölgy from Lipót Göbl, a miller from Buda. (The area was named Leopoldfeld or Lipótmező ['Leopold's field'] after its previous owner). Today the plot is under 116 Hűvösvölgyi Road.

Finally, King Franz Joseph ordered the construction based on plans by the architectural adviser Lajos Zettl. Work began in 1859 and lasted until 1868 overseen by Henrik Drasche. The Royal Hungarian Mental Asylum began operation on 6 December 1868 with three hundred patients.

Postcard of the main gate of the asylum from the 1900s (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The four-storey building designed in a late-romantic style was originally intended to house 800 patients, but could only support 500 in the end. However, it should be noted that alongside wards and rooms for patients, the hospital also included flats for doctors, other staff accommodation, a kitchen, offices and storerooms. The chapel was a central fixture, later decorated with stained glass windows by Miksa Róth. The building also contained a theatre for patients, a salon with a piano, and a swimming pool, and a research laboratory for the medical staff.

A 50-acre-park surrounds the second-largest building in Budapest. The participate of the mental hospital was fundamentally humane. The patients could move freely (except for those who at the time were called "raging lunatics", and who posed a risk not only to themselves but others). Several well-known artists spent time in the institution during the more confused periods of their lives. Urban legend has it that even Queen Consort Elizabeth rested here after her son Rudolf's suicide.

The mental hospital was surrounded by a 50-acre-park in which patients, nurses and doctors could rest (Photo: Pestbuda.hu)

Although the institution was designed to house 500 patients, at times during the Second World War 1600 were treated in the complex. In the 1950s, the first children's psychiatric ward in the country was established, and the institution was renamed: National Institute of Neurology and Psychiatric Care (OPNI). The attitude towards patients also changed in the period, as some of them were allowed to leave the premises for work.

In 2007 the Gyurcsány-government decided to reduce hospital capacity, leading to the closure of the hospital. The buildings were abandoned: patients moved out, doctors and staff made redundant. The building has stood empty ever since, slowly deteriorating.

Today visitors can only see the closed gates of the respected hospital (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

MAV Headquarters on Andrássy Avenue

The Hungarian Royal State Railways (MÁV) was established in 1868 a year after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise. Nevertheless, this MÁV should not be compared to the present-day rail company, as it was only one of many companies in the middle of the 19th century. However, from the beginning of dualism onwards, governments have attached great importance to rail transport (partly because railway construction increased industrial production). As a result, MÁV quickly became the dominant, and later, the only railway company in Hungary.

Meanwhile, the Hungarian National Assembly passed Act X of 1870, which set out the main guidelines for the development of the Hungarian capital, and also established the Budapest Public Works Committee. One of the most significant points of Budapest's urban development was the creation of Sugárút (literally, avenue, the present-day Andrássy Avenue). Dazzling buildings were erected one after the other on the plots along the Avenue: multi-storey residential palaces lined the road from Váczi Boulevard (today Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Road) to Körönd (literally circus, today Kodály Circus), and villas rose from Körönd to City Park.

It is thus no wonder that the newly formed Hungarian Royal State Railways wanted to build its headquarters along the prestigious route. The company acquired the double plot between the junctions of the avenue with Izabella and Rózsa Streets, between Oktogon and Körönd. Gyula Rochlitz, a lead architect for the company, was tasked with planning the building. Gyula Rochlitz also worked on plans for the Central Railway Station (present-day Keleti Railway Station), and he is presumed to have been involved in creating the first rail bridge in Budapest.

The MÁV headquarters on Sugárút (Andrássy Avenue) around 1878, photographed by György Klösz (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives)

Construction of the MÁV headquarters began in 1875 on 73–75 Andrássy Avenue and was completed in 1876. A highlight of the renaissance revival palace was its main lobby, decorated with four cast-iron caryatid lamp holders from Paris.

Deplorable conditions are hidden by the weathered plaster of the walls (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Over the years several changes were made to the building. Among others, a complete loft conversion was completed and an auditorium built in once of the internal courtyards. A smaller renovation was also completed in 2006, but the MÁV management surprisingly moved out of the building in 2008.

The condition of the palace has deteriorated rapidly since. Plaster and whitewash are falling from the walls; the flooring of the rooms is bulging in places. During heavy rain, the cellars are often flooded with sewage, and the once imposing palace is soaked from above due to its broken roof. The Hungarian National Trust has attempted to sell the building several times to no avail.

Gross House (former headquarters of Postabank)

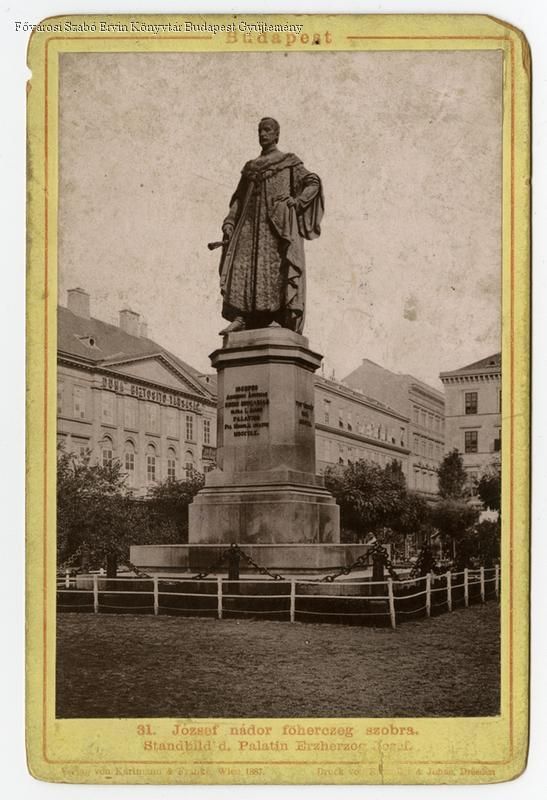

The goal of the Beautification Committee established by palatine Joseph at the beginning of the 19th century was tasked with the development and beautification of Pest. As part of this, an effort was made to create regular streets and squares. this led to the destruction o the Salt Offices and connected warehouses in the 1820s and created the rectangle that is today József Nádor Square.

Known as the most Hungarian Habsburg, the palatine believed a walking plaza should be built in the area. Count István Széchenyi agreed with the concept but would have preferred a park with trees. As the debate dragged on, the first investors began to purchase the valuable land around the square. The merchant Ferenc Gross was one of these investors, and he managed to get a hold of the 1/a corer plot. The merchant commissioned the young József Hild to design a palace for the new location.

The Gross Palace was eventually built between 1824 and 1825 and is one of Hild's earliest recorded buildings. The architect of the Reform Period designed a two-storey corner house in the classicist style, with the main facade looking towards József Nádor Square. The classicist character of the building was later emphasised by two sculptures placed in its arcade: copies of the Apollo and Athena statues from the nearby Diana Bath – also designed by Hild – were added.

The statue of Palatine Joseph on the square, Gross House visible on the right (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The arcade was once of the most prominent features of the building. The Kávéforráshoz café operated under the colonnade, and the Danish story writer Andersen is also said to have visited in 1841. From 1860 the Blumenstöckl (bouquet) opened to be frequented by artists and politicians. Then Lajos Gundel moved in and operated his famous restaurant from 1872 to 1876.

In the 1870s a casino was opened in part of the building, and it continued to house several financial institutions and public companies. A restaurant on the ground floor remained opened with slight changes until the siege of Budapest in 1944–1945. This was when a bomb hit the building. The damage was only repaid in 1948. Towards the end of the decade, a cabaret opened in a room on the ground floor, and the famed Rodolfo is said to have performed there.

As a precursor to the fall of communism, a two-tier bank system was reintroduced to Hungary in 1987. As a result, merchant banks could be opened. The Post Savings Bank (Postabank és Takarékpénztár) was created in 1988, and secured the Gross House as its headquarters. However, in 1997 the institution entered a long downward spiral, and it left the building in 2002. Since then, the palace has stood empty.

Last year, József Nádor Square was renovated. This resulted in a sharp contrast between the dilapidated building, over two-hundred years old, and one of the final standing memories of a classicist Pest, and its flamboyant home, the renovated plaza.

The contrast between square and building (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Fashion Hall, later the Otthon Department Store

Ever since the construction of Erzsébet Bridge and the widening of Rákóczi Road, it has been defined by transport. While the Public Wok Committee was reluctant to run trams on Andrássy Avenue (leading in part to the construction of the Millennium Underground), trams tracks quickly appeared on Rákóczi Road.

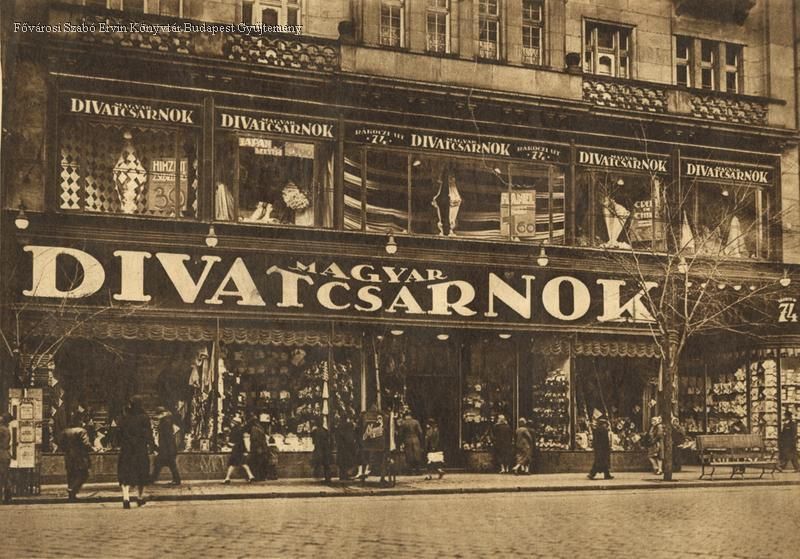

However, traffic at the time was still sparse compared to the modern-day. As a result, a slew of various shops opened along the road. The house under 74 Rákóczi Road was one of these. Designed by Sándor Löffler and Béla Löffler, a shop known as Magyar Divatcsarnok ('Hungarian fashion hall') opened on the ground floor in 1921, run by Pál and Antal Ruttkai. The clothes in the shop were chiefly decorated with motifs taken from the folk clothes of areas that had been lost after Trianon and quickly became popular in a Budapest that was reeling from the treaty.

Display of Magyar Divatcsarnok in 1927 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The shop's success is apparent in its constant expansion into neighbouring premises. Finally, Lajos Kozma planned the unification of the various business locations in 1928, leading to the creation of a common storefront. The interiors received modern decoration emphasising marble and bronze.

Interior of Divatcsarnok in 1928 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The Second World War caused the first setback in the shop's history when the building complex was damaged. Nevertheless, this could be repaired. Not so in 1956, when several buildings were heavily damaged, and the house under 72 Rákóczi Road was eventually torn down.

The shop, now simply Divatcsarnok moved to the Párizsi Nagyáruház on Andrássy Avenue in 1958. The damaged building was restored according to plans by József Csapó. The furniture shop known as Otton Áruház ('home shop') opened in 1961. Selling everything from simple ready-to-assemble furniture to carpets and lampshades, the shop specifically targeted those living in panel housing estates (large blocks of flats constructed form pre-fabricated concrete blocks).

Otthon Áruház under construction in 1961 (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives)

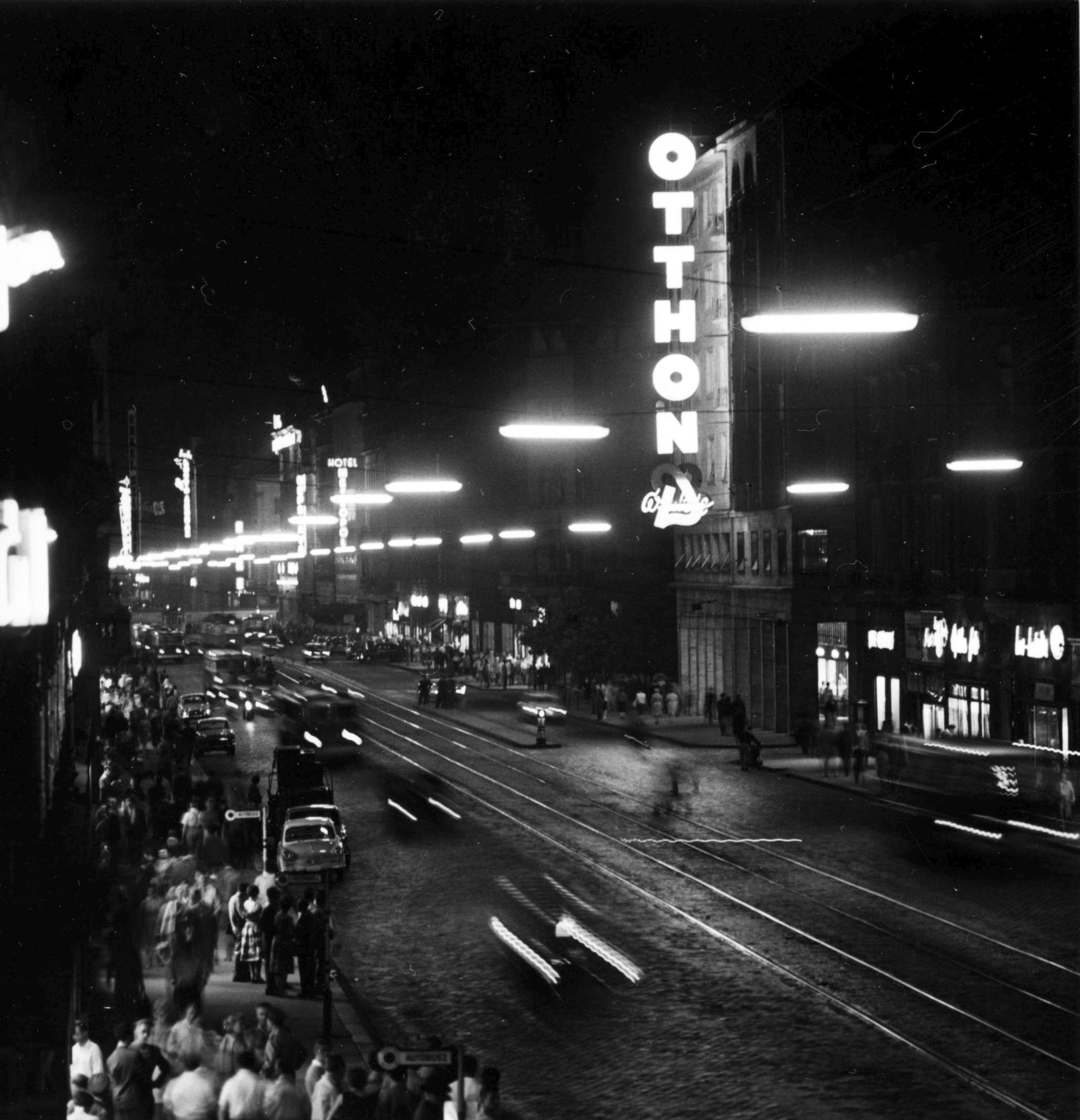

The emblematic neon sign of the shop in 1964 (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives)

While the shop was popular at first, it quickly entered a slow but steady decline. Following the completion of the M2 metro line, tram service along Rákóczi Road was abolished in the mid-1970s. The road essentially became an urban motorway. As traffic increased the width of pavements decreased and shoppers became more purposeful.

Domus was the first to draw customers away from the shop with its larger offering, and in 1990 IKEA accelerated the demise. Otthon Áruház went bankrupt, and the premises has stood empty since 2002. Today, only a weathered neon sign on the facade of the building reminds us of Budapest's first furniture shop.

The neon of the former shop is badly worn (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Nagyvásártelep – The great food market

After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, and the unification of Pest, Óbuda and Buda to form Budapest in 1873, the city developed rapidly. By the National Millennium celebrations in 1896 Budapest was a metropolis. Naturally, its population had also soared. To serve the influx of new residents, a series of market halls were built, following Western European examples.

First, the Central Market Hall on Fővám Square was opened in 1897. The largest was followed by smaller halls on Batthyány Square, Hunyadi Square, Hold Street, Klauzál Square and Rákóczi Square. However, these were not satisfactory after the city's population continued to grow after the turn of the century. The situation reached a turning point, when vendors who could no longer fit into the Central market Hall began selling their goods on Fővám Square, obstructing traffic.

Finally, in the late 1920s, the capital decided to create a new, food supply centre to meet the ever-growing demand. A plot between Közvágóhíd ('public slaughterhouse') and the Ferencváros port was chosen, and the market hall constructed based on plans by Aladár Münnich in 1930-1932.

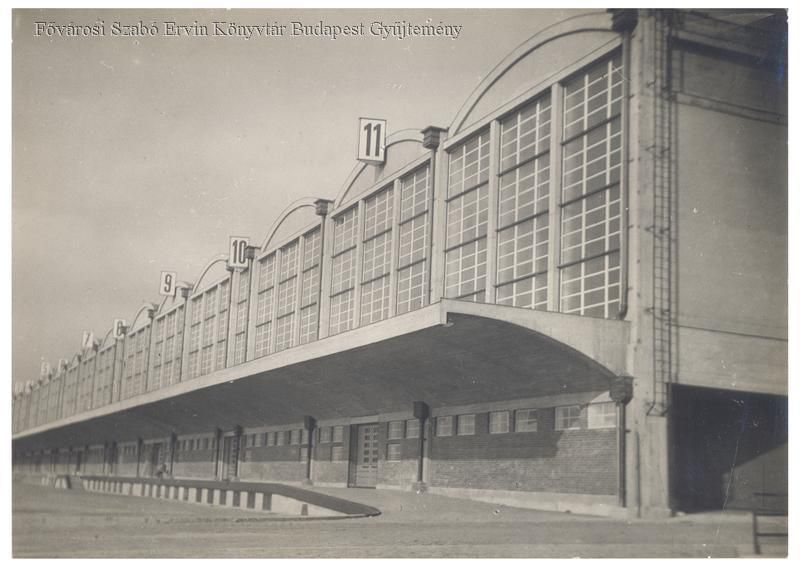

The hall of Nagyvásártelep in 1932 (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

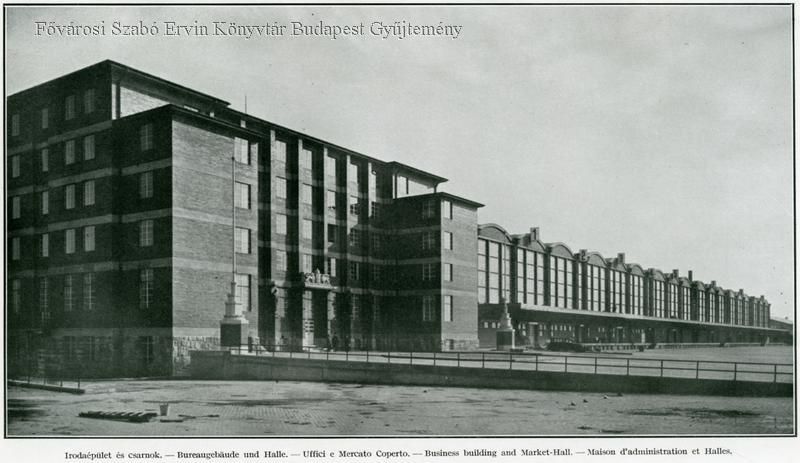

The two central buildings of Nagyvásártelep were the market hall and the office building. Goods were moved to the 247-metre-long, 42-metre-wide and 17-metre-high market hall by rail, boat and trucks. A cooling warehouse and a furnace were housed beneath the building. The market hall was connected to the Art Deco office block with a small bridge. The block housed a post office, a police station, a customs office, a boiler room, and offices for vendors.

Four statues by Béla Ohmann decorated the red brick facade. These visualised a farmer, a fisherman, a gardener and a market vendor. The Budapest coat of arms was also displayed, and two flag poles placed before the entrance. After the completion of the two central buildings, several outbuildings to serve them were built.

The office building of Nagyvásártelep after completion in 1932 visible in eh foreground (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

After the Second World War, Nagyvásártelep was also nationalized. As a result, its slow decline began. Following the fall of communism and the opening of Nagybani Piac ('wholesale market'), Nagyvásártelep was closed. The two central buildings (the office building and the hall) were declared historical monuments in 2004.

Nagyvásártelep has seen better days (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Since being abandoned the building have begun to decay, several panes of glass are missing from the market hall its walls covered in graffiti. The windows and doors of the office block are gone, and the statues battered by weather and hooligans.

Cover photo: The MÁV headquarters on Andrássy út (Photo: Both Balázs/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration