Today, the classicist building of the Óbuda Synagogue is almost lost between the panel towers. Sadly, the eye is more likely drawn to the neighbouring Aquincum Hotel and Árpád Bridge. However, once, Óbuda consisted nearly entirely of single-storey houses and the synagogue, considered one of the most beautiful in Europe, rose above them.

.jpg)

The main facade of the Óbuda Synagogue. The ornate tympanum and its six columns are clearly visible (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Its history is, unsurprisingly, deeply intertwined with the history of the Jewish community in Óbuda which historian Éva Gál has examined in several writings. In 1820, when the Synagogue was built, the Jewish community in Óbuda was one of the largest communities in Hungary. Naturally, the new Synagogue was also intended as a building of a self-representation. (The current building is the fourth synagogue to stand on the site. The first, small and simple house of worship was continuously replaced with larger, more beautiful, and modern buildings.)

The Jewish community formed at the beginning of the 18th century, and an Óbuda owned by the Zichy family. At the beginning of the 19th century, most cities forbade the settlement of Jews, leading to communities forming on large estates, where they were allowed to settle in exchange for protection money, the so-called Schutzgeld, paid to the landlord, in this case, Count Zichy. The Count benefited twofold, from the growing Jewish community as there were many grocers and traders among them. This lead to an increase in trade on the estate, which also included the Count's goods.

Beyond, industrial and agricultural trade, the community also engaged in traditional Jewish professions, working as bartenders, distillers, shopkeepers, and doormen. The former were generally rich, while the latter often lived in deplorable conditions.

Throughout the 18th century organised migrations and immigration happened into Hungary, as a result, the national population, and that of Óbuda, grew rapidly. The Jewish community grew above the average in Óbuda. Most of the new settlers came from Moravia, Poland and the Czech Republic, but families from Austria or Italy also arrived. It is little surprise that Óbuda attracted settlers living from trade. It was also close to Buda, the capital, and Pest, an economic and trading centre. Of course, it would have been better for them to settle in Pest, but throughout most of the 18th century, until Joseph II's Edict of Tolerance for Jews entered into force in Hungary in 1783, they were forbidden from moving to Pest. (The community in Óbuda remained significant even after the ban was lifted.)

The current synagogue is the fourth building on the site, but little is known about the first two. There was certainly a house of prayer in the area by 1727. A disputed inheritance within the landowner Zichy family led to the destruction of the school building called Judenschule.

The building was eventually rebuilt in 1732. The third synagogue was built between 1767–1769. (By the time, Óbuda was no longer in the hands of the Zichys, but owned by the Royal Chancellery.) A few details of this building are known. Máté Nepauer (or in another variant Mátyás Máté Nöpauer) was commissioned for the construction. The master-builder from Buda had built the Saint Anne's Church in Felsőviziváros and the Catholic Parish Church of Újlak, and thus had experience with religious buildings.

The opening ceremony of the renovated Óbuda Synagogue in 2016 (Photo: obudaizsinagoga.hu)

The contract with Nepauer stipulated that "the new synagogue, like the previous one, should be built of good materials, stone and marble, and four columns should support the vault" – writes Éva Gál in the 8th 1982 issue of the Budapest periodical. While community members had chosen an experienced master-builder, they were not satisfied with the new synagogue. It was judged unnecessarily expensive and over the top. Soon it became clear that the foundations had not been lain properly either. As a result, the building began to collapse after a few decades. Major reconstructions were needed as early as the 1780s, and in 1817 the community decided in favour of a complete reconstruction.

Information about the beginnings of construction can be found in the Community records of 1820. Two master-builders submitted plans: András Landherr from Pest, and the greatest artists of Hungarian classicist architecture, Mihály Pollack. As seen in the Architecture and Applied Arts volume of the series Hungarian Art in the 19th Century, the assembled committee chose Landherr's plans, simply because they seemed to be significantly cheaper.

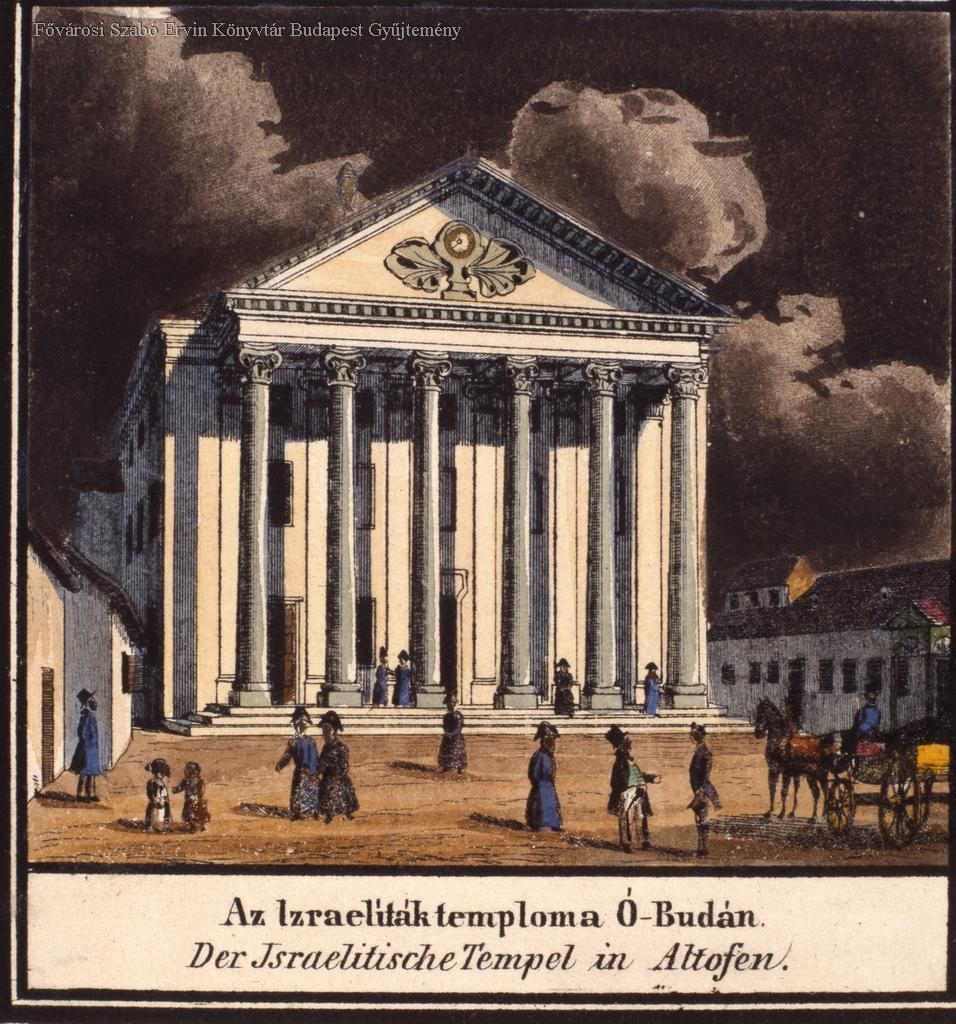

Carl Vasquez, The Church of the Israelites in Óbuda, 1837 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The Óbuda Synagogue – like other synagogues in the country – conforms to the dominant architectural style of the era, classicism. This should be noted because Jewish architecture later developed a unique style (e.g., the Rumbach Street Synagogue). However, there is no sign of such a style in this period. Few signs, Hebrew inscriptions or depictions of The Tablets of the Law on the main facades of these simple, rectangular buildings without towers, betray the function of these structures.

As mentioned, the synagogue always aimed to represent the local community's social standing. Thus, it is of little surprise that the Jewish community of the time constructed a large-scale building. On the west side, the main facade is commanding with its monumental, protruding portico, and tympanum supported by six Corinthian columns. The Hebrew inscription on the tympanum and the representation of the Ten Commandments of Moses refer to the building's function.

Two Tablets of the Law on the tympanum of the Óbuda Synagogue in 2010 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The Óbuda Synagogue in the 1930s (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

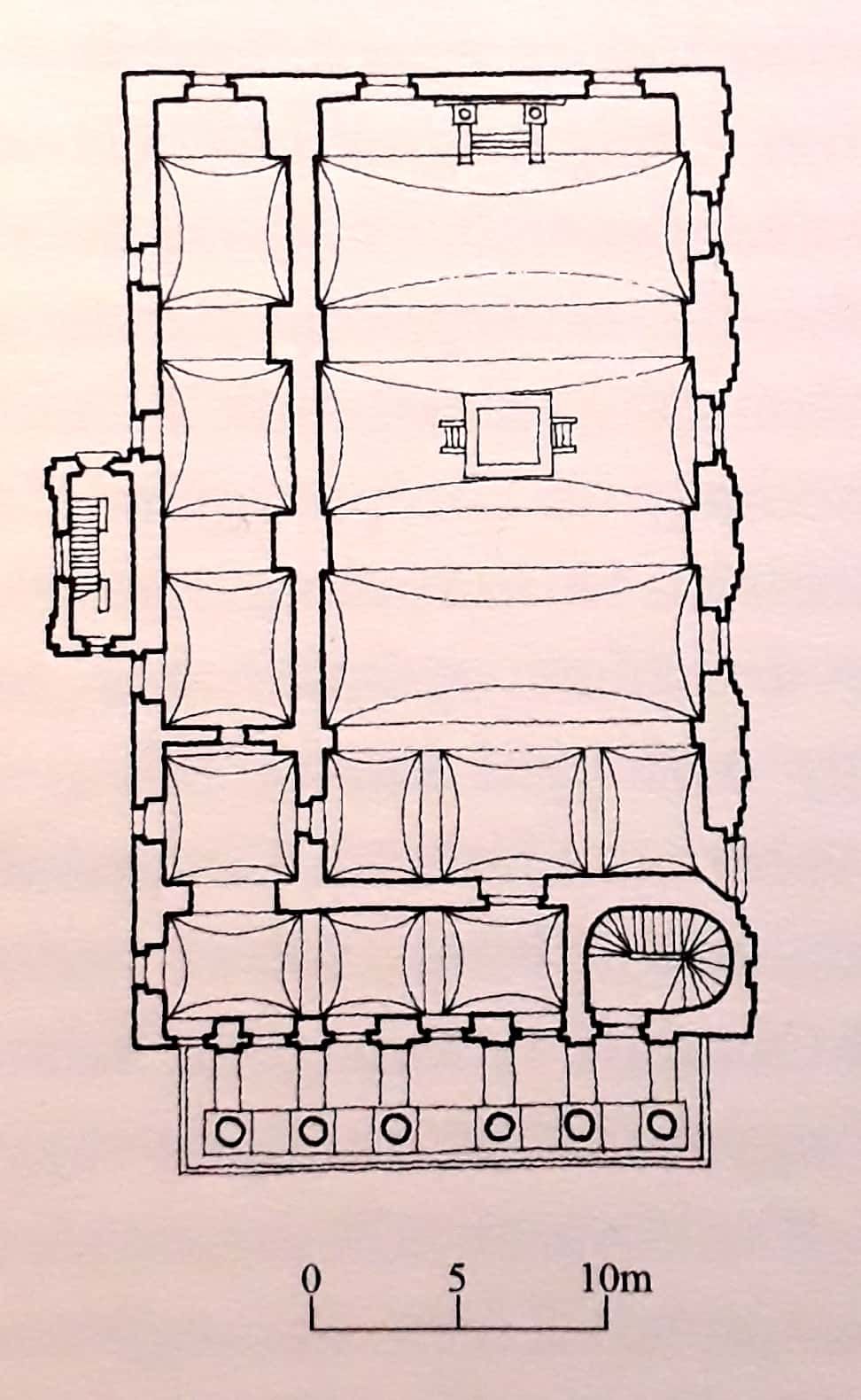

Like synagogues in general, the Óbuda Synagogue consists of two rooms, the lobby and the sanctuary. According to its traditional design, men were seated on the ground floor, while women were seated in the L-shaped gallery. Separate entrances for men and women can be observed on the floorplan, the latter leading directly to the gallery.

Floorplan of the Óbuda Synagogue (Source: A magyar művészet a 19. században, Építészet és iparművészet, 2013.

ed. József Sisa – 'Hungarian art in the 19th century, Architecture and applied arts')

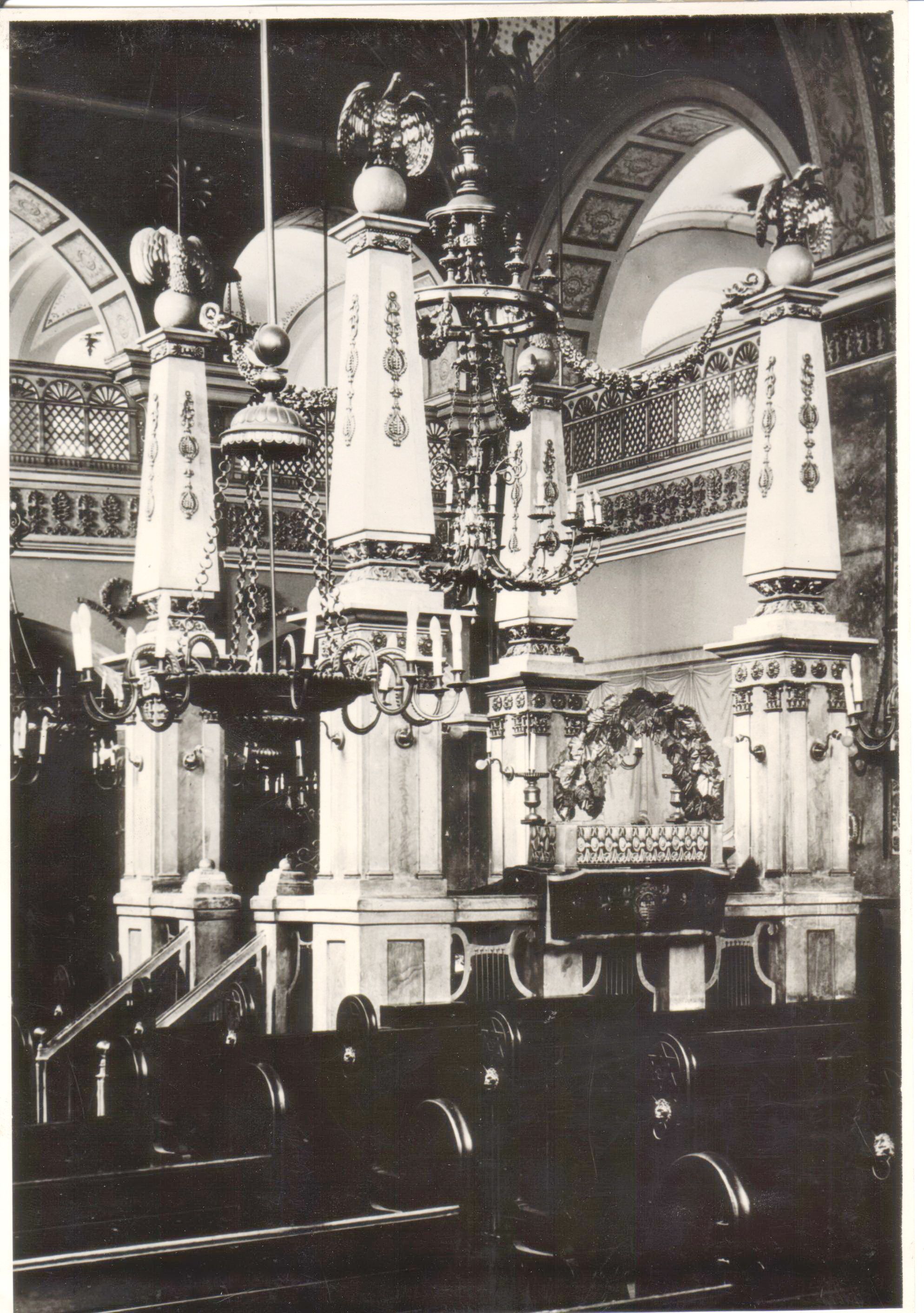

The most important and most ornate part of the synagogue is the east wall, i.e. the mizrah, where the holy ark is located atop a few stairs. At the centre of the sanctuary stands the ornate bimah, the platform holding the reader's table.

The interior of the Óbuda Synagogue in the 1950s. The picture shows the eastern wall, the mizrah, and the holy ark (Photo: obudaizsinagoga.hu)

The interior of the Óbuda synagogue, the bimah in the 1950s (Photo: obudaizsinagoga.hu)

As noted above, the building was designed by András Landherr, a master-builder from Pest. However, Landherr was not a prominent figure in Hungarian classicist architecture. While his surviving buildings are pretty, they do not hold any particular artistic value. How can the Óbuda synagogue he designed be one of the most outstanding examples of Hungarian classicism? The answer may lie in Mihály Pollack, who submitted the other plan. An expert on classicism, Anna Zádor writes in The History of Hungarian Classicist Architecture that the building's plans may have been inspired by Pollack but completed by Landherr. This may also be indicated in the decision to commission the stuccator János Maurer, to complete interior decorations. Pollack had worked with Maurer several times.

The main facade of the Óbuda Synagogue around 1930, tram 51 in the foreground (Photo: obudaizsinagoga.hu)

Cooperation between Pollack and Landherr can also be discerned from differences in the details of the building. The classicist main facade's proportions and design are reminiscent of the great master, while the baroque nature of the window frames and decoration is probably attributable to Landherr. Furthermore, an examination of Landherr's other synagogues, such as the synagogues in Abony (1825) and Várpalota (1839), shows that while they are similar to the Óbuda Synagogue, they are of lower quality.

The Óbuda Sawmill in 1925, with the Óbuda Synagogue in the background

(Photo: Fortepan, Hungarian Museum of Science, Technology and Transport)

The fourth Óbuda Synagogue was built in such excellent quality that there was no need for renovations until 1900. However, in 1900, the architect Gyula Ullmann led a large-scale renovation. While the building was not changed significantly, the works resulted in Art Nouveau-style ornamentation on the interior and exterior of the buildings.

The Óbuda Synagogue in 1970, in a deplorable state (Photo: Kiscelli Museum)

The Óbuda Synagogue in 1970, in a deplorable state (Photo: Kiscelli Museum)

The building in 1946, after partial restoration (Photo: obudaizsinagoga.hu)

The community and the building endured great hardship during World War II and the Holocaust. Religious and spiritual life continued in the ruined building until the 1960s, which was then nationalised. After its partial renovation, the Museum of Textile Technology was set up in 1972, but it soon became clear that the building was not suitable for exhibitions. In 1978, the building was given to the Hungarian Televisionwhich set up a studio and a set warehouse in the building, making major changes. From 2009 onwards, the broadcasting company no longer used the building, and it stood empty.

The synagogue building renovated in 1972 but not serving its original function (Photo: Kiscelli Museum)

Between 2010 and 2016, the Egységes Magyar Izraelita Hitközség ('United Hungarian Izrealite Community') carried out a large-scale, complete renovation of the synagogue, returning it to its original function. As the synagogue’s own website reads: “The synagogue has once again filled with life and is not only the most important site of local spiritual life but a living, open and prosperous community. The services on Friday evenings, Saturday mornings and weekday morning prayers, communal meals, study sessions, community events, and events for children every Sunday morning are evidence of this.”

The Óbuda Synagogue before renovation, in 2009 (Photo: obudaizsinagoga.hu)

The interior of the synagogue after renovation in 2016 (Photo: magyarkurir.hu)

Cover photo: The Óbuda Synagogue in the 1930s (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration