The carnival period lasts from the feast of Epiphany, which brings an end to Christmas celebrations, to the day before Ash Wednesday, Shrove Tuesday, and is traditionally characterised by banquets, balls and fun. The Pest and Buda of old were famous for their balls and dances. The importance of this tradition was stressed by the 20 January 1929 issue of Budapest Hirlap Vasárnapja:

“Looking into what the citizens of Pest inherited from their ancestors one should focus on the carnival period. Love of the carnival season, or rather a love for balls and dances, is the only inheritance that the citizens of Budapest try to pass on to their descendants without change.”

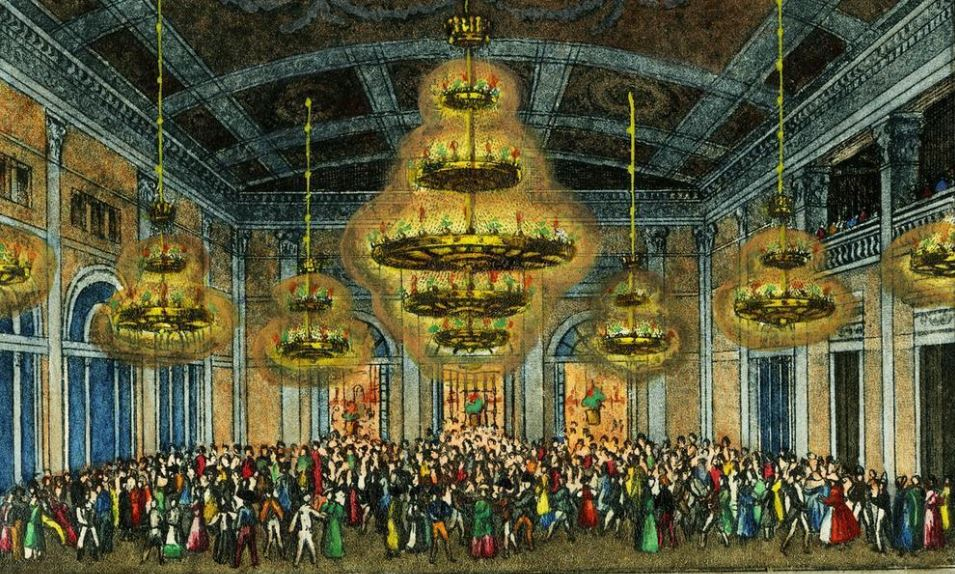

A Ball in Redoute, engraving by Móric Schwindt based on a drawing by Károly Schwindt from 1837

It seems that this was once a fact of common knowledge, which had a reputation near and far. As a result, travellers from abroad also reported on dances and balls in Pest. It was also customary for those living in the countryside to visit the city during the days of the carnival. Gyula Krúdy, a knowledgeable member of the Buda and Pest of old also noted this: “Guests filled every room in the Arany Sas and the Griff” he writes in Régi pesti fametszet (‘wood engraving of old Pest’). “As soon as a ball ended the next would begin: the lawyers’ ball had just happened, and the Pest County ball was just around the corner. The porters greeted the omnibus that slid in through the gates with shouts and moved the bags with a cosmopolitan fervour. It was as if the whole of Hungary came to Pest for the carnival (...)”

Arany Sas on the former Újvilág (now Semmelweis) Street, which enjoyed a full house during carnival season

Arany Sas on the former Újvilág (now Semmelweis) Street, which enjoyed a full house during carnival season

(Source: Hungarian Museum of Commerce and Hospitality)

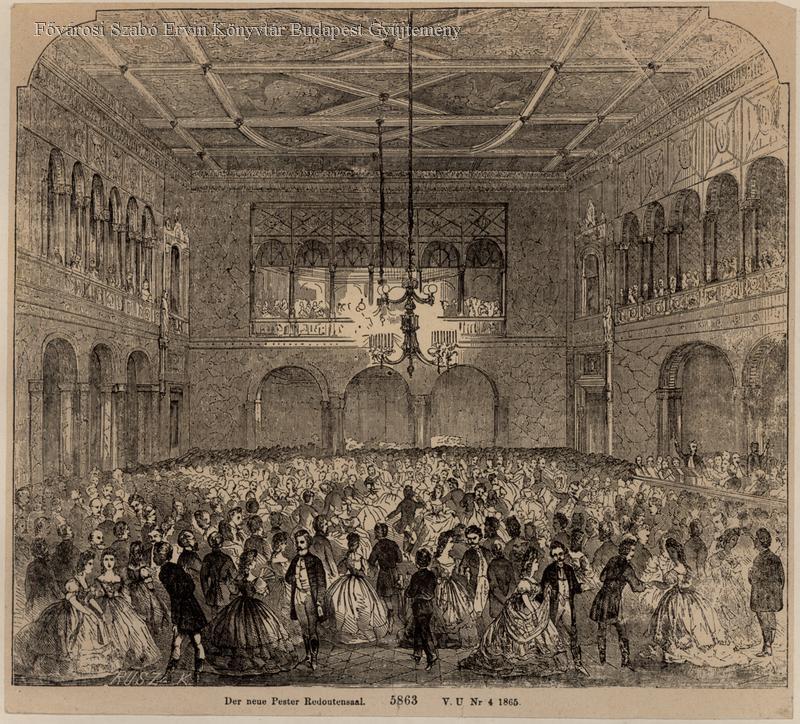

Lawyers’ Ball in the Great Hall of the Vigadó in 1865 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Alongside guests from far afield, the residents of both Buda and Pest would visit balls held across the river. So, it often happened that balers would wait for hours on the banks of the Danube to cross the semi-frozen river by boat, on their way home – often made more hazardous with ice flows.

In the famous masquerades of the Pest bourgeoisie and the costumes that hid all social and financial differences were diverse. Swords and spurs were an indispensable part of men’s wear, despite the latter often posing a threat to ladies’ dresses.

Shooting Assiociation's Ball in the grand hall of the former Hét Választófejedelem Tavern (Source: László Siklóssy: A magyar sport ezer éve – 'One thousand years of Hungarian sport', Volume II)

The duration of balls and their possible dates were regulated by a royal decree issued by Maria Theresa in 1772. Balls could begin the day after Epiphany. Two or three balls could be held per week, from eight in the evening to three in the morning. In the traditional Catholic calendar, balls could be held several times a week from Septuagesima and could go on for longer: from eight in the evening to five in the morning. The revelry had to stop at midnight on the day before Ash Wednesday, Shrove Tuesday.

Zsigmond Szautner, director of the Buda Academy of Music and his family as a mandolin ensemble at a costume ball (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 32100)

Maria Theresa’s ball decree also enforced other items: it stated that individuals of all orders and ranks could attend masquerade balls. Everyone was allowed to wear the mask or costume they wanted but bared those in bad taste: such as priestly or monastic dress. Those in such costumes were not allowed in ballrooms, and be escorted out if they somehow were to gain entry. The costume could only be worn as long as ballers were in the ballroom, and on departure, attendees were obliged to take off their mask and reveal their identity in front of the cash register.

As mentioned, men wore swords to balls, but the royal decree forbade the use of weapons at the parties. It also stated that anyone had the right to arrest someone wearing a mask on the street and lead them to jail. Those wearing masks were only allowed to travel by carriage or litter. Gambling was also banned by the provision, which also deducted six per cent of the ball’s income as a tax, to be collected by a commissioner appointed by the city council.

Ball for the management and staff of the Angol Királynő Hotel in 1909 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Ball at Royal in the 1930s (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Carnival season was also a loud affair, as the 6 January 1929 issue of the Friss Ujság periodical noted. Street organs accompanied celebrations in Óbuda and brass bands in City Park. Various glee clubs and choirs also gave concerts in the period.

Supporting charities was also a tradition of the season, with charity fairs held in Lloyd Palace on the Pest Danube bank.

Our ancestors did not forget charity during the carnival season. Public kitchen during carnival, engraving by Ferenc Kohler, 1875 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Finally, a glance at the most important venues is worthwhile. In Pest, the former Hét választófejedelmen tavern between Váci Street and Aranykéz Street, the ballroom of which hosted a Franz Liszt concert when the composer was 11 in 1823, was a central location. Large balls were of course held in the Vigadó and its predecessor, the Redout, the Európa Hotel near the Pest end of Chain Bridge, and the ballrooms of other major hotels, and the Tüköry Beerhall, which stood on the plot of the present-day Vígszínház, and József Hacker’s Redoute in Terézváros. The Fácán Tavern in Zugliget was a popular venue in Pest.

Beyond these significant balls, several smaller dances were held around the city. Every level of society and every social association of some standing organised a ball. For example, the 27, January 1895 issue of Budapesti Hírlap reported on a ball held by the “deaf-mute” in the old shooting range.

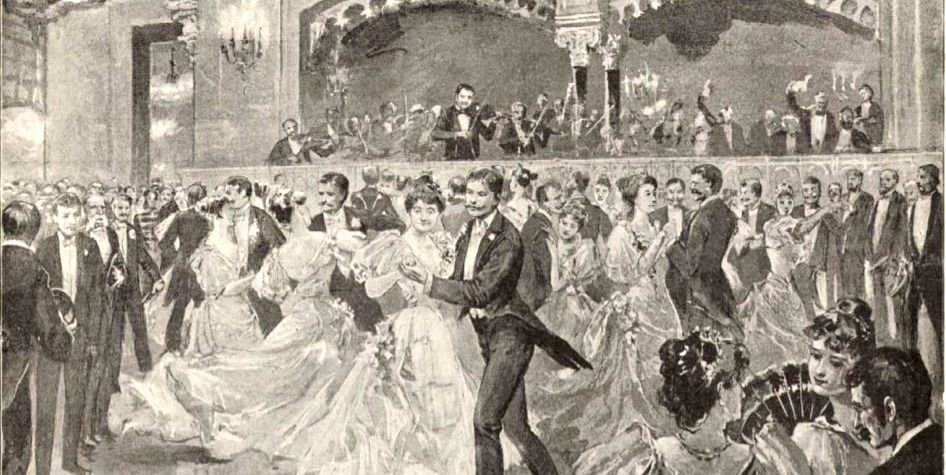

Ball in the Pest Vigadó on an engraving based on a drawing by Károly Cerna published in the 9 February 1896 issue of Vasárnapi Ujság.

The most lavish ball of the year took place in the Royal Palace of Buda. Court balls were attended by the King and organised with great splendour and an army of guests. In all, 1630 invitations were sent to the 1899 court ball.

Franz Joseph at a court ball in the Hungarian capital (Source: A király könyve – ‘The king’s book’, a richly illustrated memorial album about the life of the king)

In the quiet of 2021, these carnivals of old seem even more distant than they actually are. But if we listen carefully, we can hear the sound of the street organ playing in Óbuda, and the heart-warming sound of a brass band in City Park rising through a winter night.

Cover photo: Ball in the Pest Vigadó on an engraving based on a drawing by Károly Cerna published in the 9 February 1896 issue of Vasárnapi Ujság.

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration