The exhibition consisted of two large units housed in different buildings: the material presenting contemporary international and Hungarian architecture was in the Műcsarnok, while the Hungarian style aspirations took place in the building of the National Salon on Erzsébet Square. The programs of the congress also affected several other prominent venues: the event began in the ceremonial hall of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences with the opening speech of Minister of Culture Kunó Klebelsberg, after which Mayor Ferenc Ripka welcomed the participants.

In the afternoon, after the solemn opening of the exhibition on Erzsébet Square, the International Standing Committee of Architects met in the boardroom of the Hungarian Association of Engineers and Architects. The next day the exhibition in Műcsarnok opened, and in the afternoon a trip to the Buda hills was organised for the guests. There were also sightseeing walks and museum visits the following week, but by then the serious negotiations were already in the lead.

Former building of the National Salon on Erzsébet Square (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 95206)

Architects' training, the chambers of architects, the issue of architectural copyright were also discussed, and architectural acoustics was talked over for the longest time. Presentations were given by renowned architects such as the German Fritz Höger, designer of the famous Chilehaus in Hamburg, and the Sweden Ivar Tengbom, whose name is associated with the Stockholm Concert Hall, the venue for the Nobel Prizes.

Fritz Höger: Chilehaus, Hamburg (Source: commons.wikipedia.org, by Esther Westerveld from Haarlemmermeer, Nederland)

Ivar Tengbom: Stockholm Concert Hall (Photo: Fortepan/Kieselbach Gyula)

Drechsler Palace at 25 Andrássy Road, where the headquarters of the Hungarian Association of Engineers and Architects operated (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, photographs by György Klösz, No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.06 .53)

Worthy of the colourful programs, the two exhibitions were also extremely large, with a total of about 2,900 architectural works to be admired by visitors - at least on plans, photos and models. The exhibition in Műcsarnok was the larger one, and even new walls had to be built there to fit all the works in the building: the interior was expanded to 21 halls. By the way, the walls were built of Hungarian patent diatomaceous soil made by the Parafakőgyár. In the first room - as a presentation of the host - the National Committee of Monuments presented outstanding memories of the history of Hungarian architecture.

With the 400 exhibited paintings - selected by Jenő Lechner - it was proved that Hungarian art has always adapted to European trends. The monuments of the torn-off parts of the country have been given a special section so that the international community can understand the injustice suffered in our country. In the other twenty halls, according to the concept, the architectural achievements of the last ten years of the twenty exhibiting countries were presented, with a total of more than 950 plans and photos.

Of course, Hungary also appeared at the exhibition. According to the decision of the organisers - Secretary of State Róbert Kertész K. and architect Gyula Wälder - the Hungarian material was divided into three groups. In the first group, the memories of 19-20th century historicism were collected by Oszkár Fritz, and in the other, the modern buildings still budding praised the work of Virgil Bierbauer. There were a total of 286 photos in these two groups, yet we could not really impress Western colleagues who would have sought a larger number of modern architecture. In Hungary, however, due to the trauma of Trianon, conservative, historicising architecture was still prevalent in the 1920s, and modernism largely existed only in plans.

The third group presented national style aspirations. As this is a very heterogeneous phenomenon, the 247 works featured here have been grouped into separate sections by the directors to make it easier for foreign guests to understand. In the first room, the works of Frigyes Feszl (designer of Pest Vigadó) and Ödön Lechner (creator of the Museum of Applied Arts), the two creative geniuses, appeared.

Frigyes Feszl: Pest Vigadó (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

In the second, the visitors got to know a wide range of Ödön Lechner's followers (for example, Marcell Komor and Dezső Jakab). In the third, the architects of the Transylvanian folk art trend also featured many works (for example, the buildings of Károly Kós in the Budapest Zoo). The works of Jenő Lechner and István Medgyaszay, who tried to create the Hungarian architectural form of expression individually, were housed in a separate hall.

Ödön Lechner: Royal Postal Savings Bank (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The exhibition reportedly achieved the desired effect, with guests extremely amazed at the diverse trends. In particular, the Eastern origin of the Hungarians and the Indus kinship attracted attention, to which the Finnish architect Lindgren reacted as follows: "I knew that the Finnish and Hungarian people were related, but I did not know that both the Hungarian and Indus people were related, so it is new to me that both the Finnish and Indus people are related!"

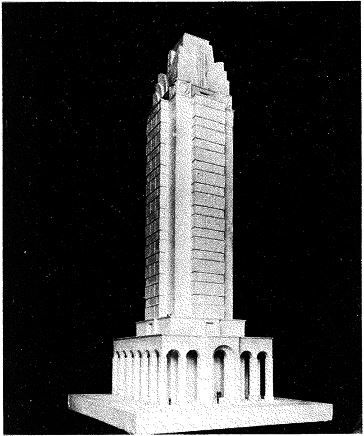

Dr Jenő Lechner: Model of the Tower of Hungarian History (Source: Budapest History Museum, Kiscell Museum)

In addition to the photos, models were also exhibited, the most significant of which was the Tower of Hungarian History made by Jenő Lechner that year. It would have been a gigantic, 130-metre-high skyscraper on the Pest Danube Bank, the top ten levels of which would have represented a century of our history. Various shops would have opened on the lower levels, and a chapel, as well as a lookout terrace, were planned at the top. Of course, the building would also have served irredentist purposes and although it was not realised, the inclusion of the model also fit into this cultural policy goal.

Although the exhibition stood for only ten days, it was also visited by nearly five thousand in that short time - in addition to the architects who came to Congress. So it was of great interest to the Hungarian audience as well. Congress itself has had good results as well: an international architectural magazine has been launched and an agreement has been reached on the following venue: in 1933, the United States of America hosted architects from around the world.

Cover photo: Drechsler Palace at 25 Andrássy Road, where the headquarters of the Hungarian Association of Engineers and Architects operated (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, photographs by György Klösz, No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.06 .53)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration