Individual political systems and historical eras also like to be represented in the names of public spaces in Budapest, and this fact, together with the many regime changes of the last century and a half, has created a very colourful cavalcade in the names of the streets and squares of the capital. If we look at the current map of Budapest, we can see that there are a lot of different names on it, but these are not only important in themselves, the number of names from different categories also has a message value. From persons living in which historical era did most streets and squares get their name? Are they real or fictional people? The recently completed interactive map , created jointly by the Budapest Archives and the team of ÁTLÓ (they also created a map of street names in Budapest referring to Trianon), helps to answer these questions.

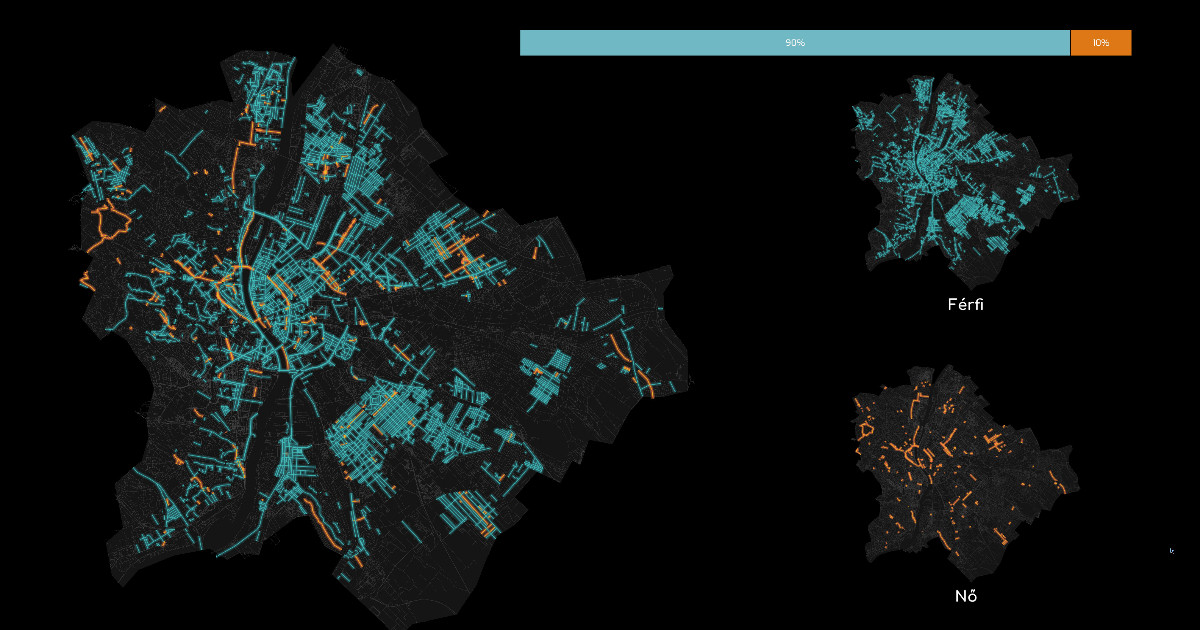

The proportion of men and women among the namesakes of streets and squares is 90-10 (photo: adatvizualizacio.bparchiv.hu)

The interactive map is, in fact, nothing more than a spectacular, easy-to-browse statistical database that can help us discover connections that would otherwise be hidden from us. It turns out, for example, that 2247 public spaces in Budapest bear personal names (flowers, seasons and other names were omitted from this map), of which 90 percent (2023) were named after men and 10 percent from women. Even more surprising, however, is that 9 percent of street names in the capital refer to a non-real person, such as Dobó Katica Street in the 19th District or Szép Juhászné Road in the 2nd District, but most of the fictitious names are simple personal names like Imre or Viola.

91 percent of the street names in the capital are named after real people, such as Karinthy Frigyes Road in the 11th District (photo: Róbert Juharos / pestbuda.hu)

The shortcoming of the map, however, is that it does not show who the name-giving person really was, as it only includes the district next to the name and whether they were real or not. However, if we had such information, we could find out that although Katica Dobó is considered by many to be the daughter of István Dobó, the castle defender of Eger, the captain never had such a child, this legend stems from Kálmán Tóth's comedy of 1862.

However, the role of art is also significant among real people: many (394) public spaces are named after writers or poets, but 219 streets or squares are also named after other artists. However, the prime is carried by leaders and soldiers: a total of 843 public spaces bear the names of statesmen (politicians), warlords, soldiers or rulers.

Plenty of public spaces bear the names of writers or poets (photo: Róbert Juharos / pestbuda.hu)

The map shows that the role of the 19th century is decisive not only in the architecture of Budapest, but also in the field of names: of the historical periods by far most(691 people) lived or died in this century, and the second most (482) are emblematic figures of the 1901-1945 period. Only 237 public areas have been named after 1945, but there are also significant sites, such as Kodály körönd or II. János Pál pápa Square. It is also interesting that a significant part of the 34 public areas bearing ancient names is named after a single person: Attila (Etele), the former ruler of the Huns, but also Szent György [St. George], who is the namesake of one of the most important and historically significant symbolic squares of the Buda Castle.

People connected to the 19th century are clearly in the majority of the namesakes (photo adatvizualizacio.bparchiv.hu)

However, a shortcoming is that the map does not show when the public areas were named apart from the last decades, ie we can only track the changes since the change of regime. The biggest wave of renaming (with 198 new names) can be traced back to the Antall-Boross government. This is not surprising, given that most of the names inherited from state socialism were then changed (or changed back) from Margit Boulevard (Mártírok Útja) to Stefánia Road (Népstadion Road). The second largest renaming wave (64 names) was in the period of the second Orbán government, when the former Moszkva [Moscow] Square was renamed Széll Kálmán Square, and the old Roosevelt Square was renamed Széchenyi István Square, but the lower embankments of Pest and Buda also got their new names, although the latter is still called by their old names by everybody.

Countless public spaces are named after former politicians and statesmen, such as Széchenyi István Square in the inner city, the former Roosevelt Square (photo: Zsolt Dubniczky / pestbuda.hu)

In Budapest, therefore, not only the houses and their inhabitants, but also the street names preserve the history of the city. Moreover, the whole country: as the capital of the nation, the renames in Budapest also have a message, and the now completed interactive map of the Budapest Archives helps us to decipher this.

Cover photo: A street in Lágymányos named after Lajos Bertalan, a civil engineer who made a lasting impression in the field of flood regulations (photo: Róbert Juharos / pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration