There were still many horse-drawn rental carriages in Budapest in 1917, despite the fact that taxis had been operating in the capital since 1913. The taxi service started so late in the capital because the lobbying power of the coachmen was strong, and they were able to prevent the appearance of competition for a long time. The war years were not favourable to motorised civil transport either, so horse-drawn carriages were part of Budapest's street scene for quite a long time. Due to the war, the number of carriages decreased, and this meant that passengers had to constantly hunt for them. In principle, it was not possible to compete in the freight rate, because it was the official price.

Carriages waiting to be used on the former Rózsa Square (today's Március 15 Square) around 1895 in a photograph by György Klösz (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives)

As a result, the travelling public found that they were at the mercy of the coachmen, who were abusing the situation. This opinion was also shared by the police, especially the new chief captain who took office at the time, László Sándor, so it is not surprising that the new chief captain's decree issued by him began with a list of abuses. This passage was also published in the 21 July 1917 issue of Az Ujság, in the article 'Against the vandalism of the coachmen':

"The abuses and transgressions committed by coachmen have reached such a scale recently that this behaviour cannot be tolerated any longer for the sake of the public using the carriages. Refusal of rides, rude behaviour, overcharging for fares and even extortion are already practiced quite regularly by some attendants, and most coachmen completely ignore the provisions of the rules in force."

The coachmen often refused transport, not only on the street, but also at the stations, and, especially at night, they were only willing to take passengers not for the official price, but much more expensive. It should be added that most carriages were not coached by the owner, but by so-called attendants, who actually rented the vehicle from the owner of the carriages, either for a fixed fee or for a portion of the freight revenue. Of course, it happened many times that the fixed fee - which was otherwise prohibited in principle - was so high that the subcontractor simply could not make ends meet.

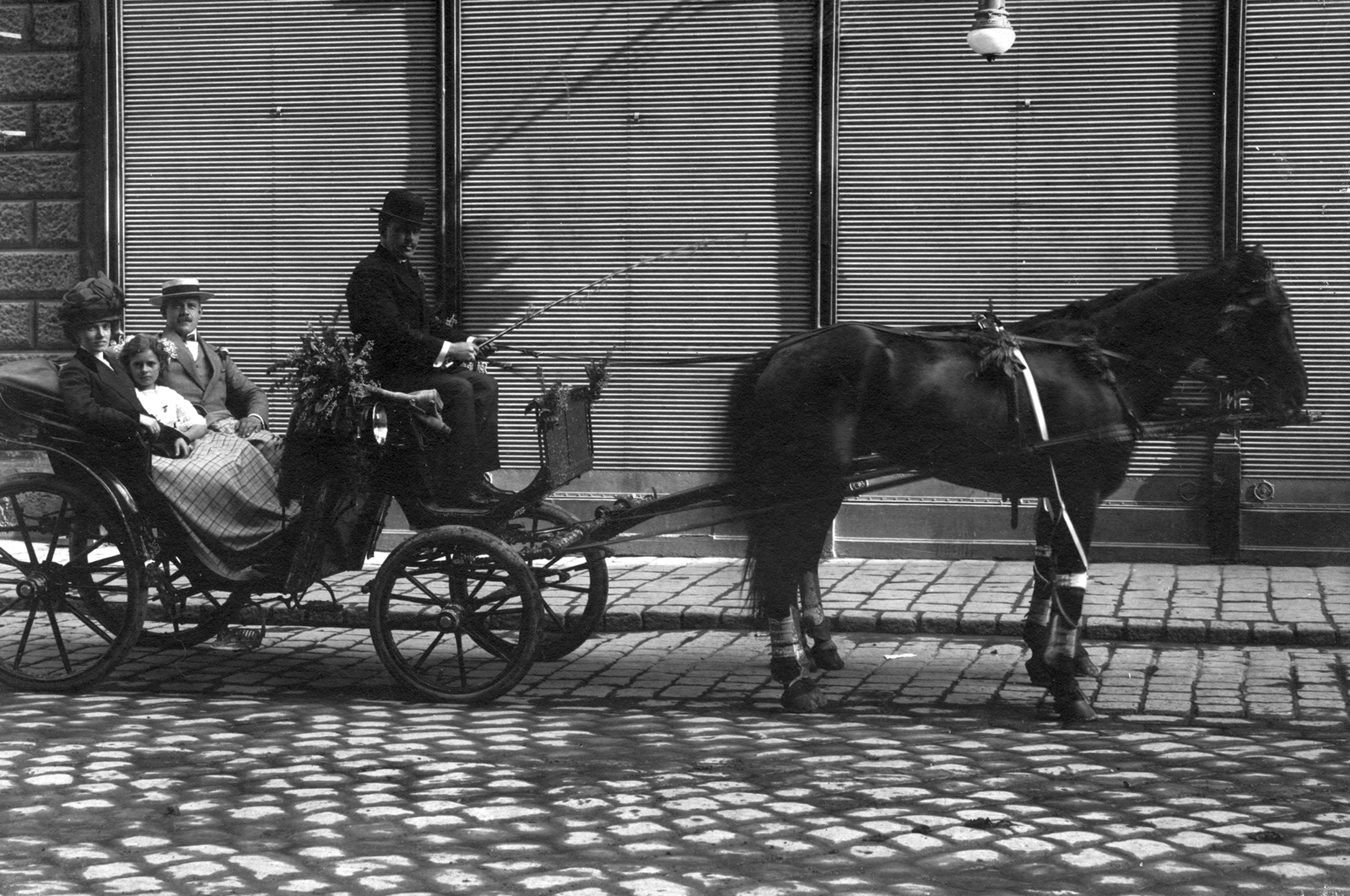

Rental carriage in 1920 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 32116)

Therefore, the attendant, who actually sat on the perch, was usually allowed to keep 30 percent of the official fare, however, even if he was able to extort a higher price from the passenger, he only passed on the fare to the owner based on the amount due according to the official price. So, if a ride officially cost 2.60, 90 pennies were paid to the attendant and 1.70 kroner to the owner, but if the passenger paid 4 kroner, the attendant only paid the owner the official 1.70. The decree read as follows:

"The coachmen who is rude to the passenger, and who keeps the fare indicator in operation either at the station or on the street, i.e., lowers its indicator flag when there is no passenger in the car, should have his license taken away immediately and be reported to the district headquarters. The police should not wait for the public to complain to them, but take action themselves, in the following way:

If they see that the passenger gets into the carriage only after negotiating with the coachman, or that the coachman wants to drive away without the passenger using the carriage, they should immediately intervene and ask if they have any complaints against the coachman. If the coachman was only willing to transport them for a specific amount, or under other, unlawful conditions, or refused to do it, his license should also be taken away immediately."

In addition, all empty rental carriages had to be checked at night, and in the vicinity of the City Park, it was also necessary to ensure that they were not used for joy-rides. The police had to strictly check everything related to the rental carriages, and the attendant who was caught in the above violations had to be banned from coaching the rental carriages for a longer period of time, or in more serious cases, forever.

The coachmen, especially the attendants, of course protested, even the idea of a strike came up, since the livelihood of many was in danger. And the police did take action, for example, on the weekend of 19-21 July, they held a multi-day raid, during which they took away the licenses of a total of 55 coachmen.

Carriages in front of the headquarters of the Hungarian General Credit Bank (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The regulation became so strict that a few days later it was refined, because if it had been followed to the letter, then traffic would have been practically impossible, so they regulated empty rides and rest periods, but for example, if a coachman fell ill or a horse was injured, they could only get out of traffic with the written permission of the nearest police officer.

When the coachmen complained to the police captain that the passengers were also rude to them, the captain gave this advice for the future, according to the 29 July 1917 issue of Magyarország:

"The coachmen themselves played their case in front of the audience. If they stick to the regulation, they will not give cause for complaints, and the passengers' behaviour will also change."

Cover photo: Postcard montage with a carriage (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration