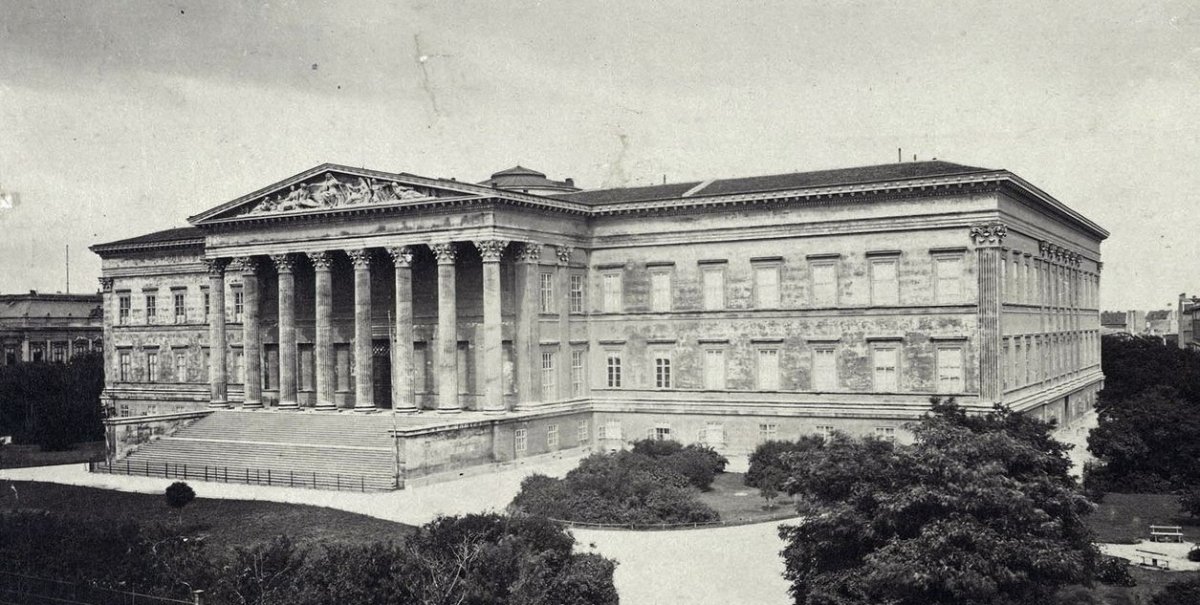

The foundation of the Hungarian National Museum - together with the National Library - was made possible by the generous donation of Count Ferenc Széchényi in 1802. However, it received an independent building only decades later, in 1847, designed by Mihály Pollack in a Classicist style. After it was completed, it did not change significantly on the outside, but its interior spaces were remodelled several times. The function also required it, since from the 1860s it was used by the House of Magnates of the Parliament, which met in the ceremonial hall. For this reason, the corridors that originally ran all the way around were interrupted by walls, and the main stairwell could only be used by the representatives. The museum staff was forced to the narrow back stairs lit by gas lamps. According to the historicising taste of the second half of the 19th century, the walls were also richly decorated with works of art, and coloured window panes were also installed.

The Hungarian National Museum in the 1880s (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.06.048)

Although in 1902 the House of Magnates moved to the newly built Parliament, the rapid growth of the museum's collection and the above-mentioned renovations resulted in the interior becoming extremely dark. After World War I, the government paid special attention to culture, so it also decided to eliminate the unsustainable conditions that had developed in the National Museum. Culture Minister Kunó Klebelsberg emphasised that during the reconstruction, the needs of modern museums must be kept in mind. Director Bálint Hóman wanted to ensure that only the library and art history collections remained in the headquarters, and that other types of artefacts - such as minerals, which at that time still belonged to this institution - were transferred to external buildings.

Bálint Hóman was the director of the Hungarian National Museum during the restoration (Source: wikipedia.org)

The Ministry of Religion and Public Education commissioned Jenő Lechner to prepare the restoration plans, as he had already researched in-depth the domestic classicist architecture decades earlier, and in 1917 he also wrote a thorough study on the building of the National Museum. During the design, the basic concept was to make the interior spaces more transparent and brighter. As a first step, he opened corridors that had been walled off for the sake of the House of Magnates, and then removed the washrooms previously created at the back staircase, so that the public could use the surrounding corridors in their entirety again. On the rear facades, he also opened some small semi-circular windows – matching the style of the building – to let even more light into the building. He also made sure that a uniform spatial composition was created on each floor, in accordance with the original spirit of the building.

The museum's decorative staircase in the 1890s (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.07.149)

The museum's decorative staircase in the 1890s (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.07.149)

The ornamental staircase after restoration (Source: Jenő Lechner: The building of the Hungarian National Museum 1836–1926)

However, Lechner did not only carry out structural transformations: the out-of-style equipment in the individual rooms was removed, and the decorative paintwork of the representative rooms (dome space, exhibition spaces) was also scraped off. Only the painting of the ceremonial hall was left, as a lithograph made in 1848 was available for that, which proved that it looked like this even in Pollack's time.

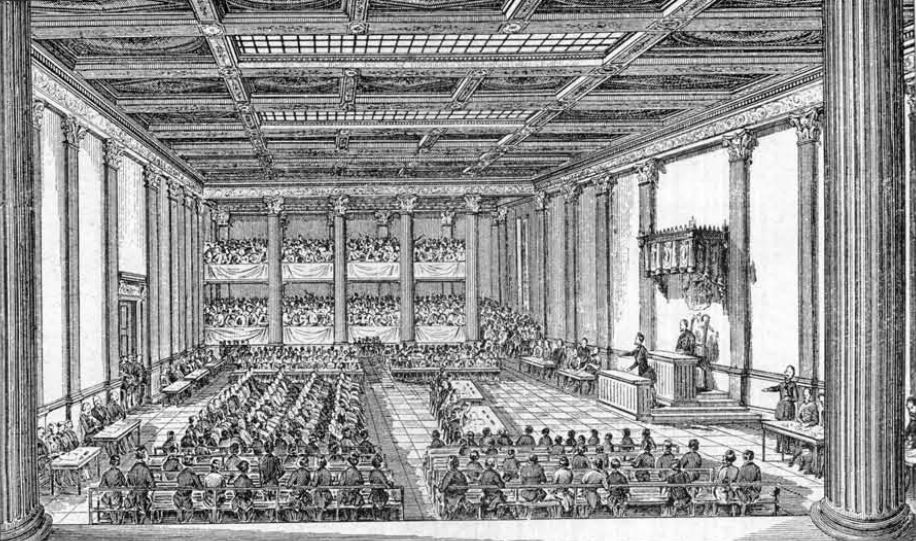

Contemporary engraving of the 1848 parliament, which met in the museum's ceremonial hall (Source: Jenő Lechner: The building of the Hungarian National Museum 1836–1926)

However, it did not show any colours, so Lechner touched it and painted the brown basic tone of the cornice frieze above the galleries to blue. Since the painting of the other representative rooms was very different from that of the ceremonial hall, Lechner assumed that they were from later, and therefore - and because their style did not match the building - he decided to destroy them. Only later did it turn out that they were also made in the 1840s, based on the plans of the young Miklós Ybl. The stained-glass windows of the main stairwell with a Renaissance style were really the result of a later conversion, so Classicist windows were built in their place, which also served to make it brighter, after that the coloured windows did not hold the incoming light either.

The ceremonial hall as the meeting hall of the House of the Magnates at the end of the 19th century (Source: Jenő Lechner: The building of the Hungarian National Museum 1836–1926)

The ceremonial hall as the meeting hall of the House of the Magnates at the end of the 19th century (Source: Jenő Lechner: The building of the Hungarian National Museum 1836–1926)

The ceremonial hall after the restoration in 1926 (Source: Jenő Lechner: The building of the Hungarian National Museum 1836–1926)

In addition, new chandeliers, wall arms, candelabra, draft doors and railings were installed. Lechner designed them in Empire style and decorated them with acanthus leaves and lotus flowers. He combined yellow and light brown colours with black for the carpentry work: the vestibule windbreak - which prevented the wind from entering at the main entrance - was otherwise a completely modern structure, yet its style is as if it had originally been inside the building. He designed the presidential table for the lecture hall in light brown cherry wood, which is decorated with half columns with black trunks. Jenő Lechner designed the applied art equipments with a great sense of style, he even made the design for the fireplace grate himself.

The candelabra of the ornamental staircase today (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Bálint Hóman's desire to remove the natural science collections was not fully fulfilled, but the interior spaces still became much more transparent: the offices were set up on the ground floor, the library occupied the first floor, the animal and mineral collection, then objects from prehistoric times to the migration period and the Hungarian cultural history collection were placed on the second floor. As a result, they were finally able to present the country's treasures in a coherent way.

As a result of the restoration, Empire-style chandeliers were added to the museum (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

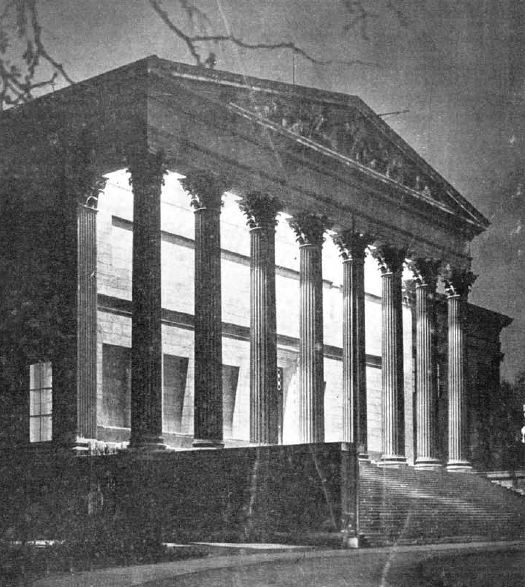

For the sake of modernisation, Lechner also made some small changes to the exterior of the building: he removed the iron railing at the bottom of the main staircase, and installed hidden lighting on the ceiling instead of hanging arc lamps in the outer lobby behind the columns. And in the inner hall, as a tribute to the great predecessors, a niche was carved into the two stout pillars, in which the statues of Palatine Joseph and Mihály Pollack were placed, both made by Rafael Monti. Lechner also planned to demolish the fence of the Museum Garden on the boulevard side, so that the building would become an integral part of the boulevard, but this has not yet been realised.

The museum's lighting was also modernised (Source: Jenő Lechner: The building of the Hungarian National Museum 1836–1926)

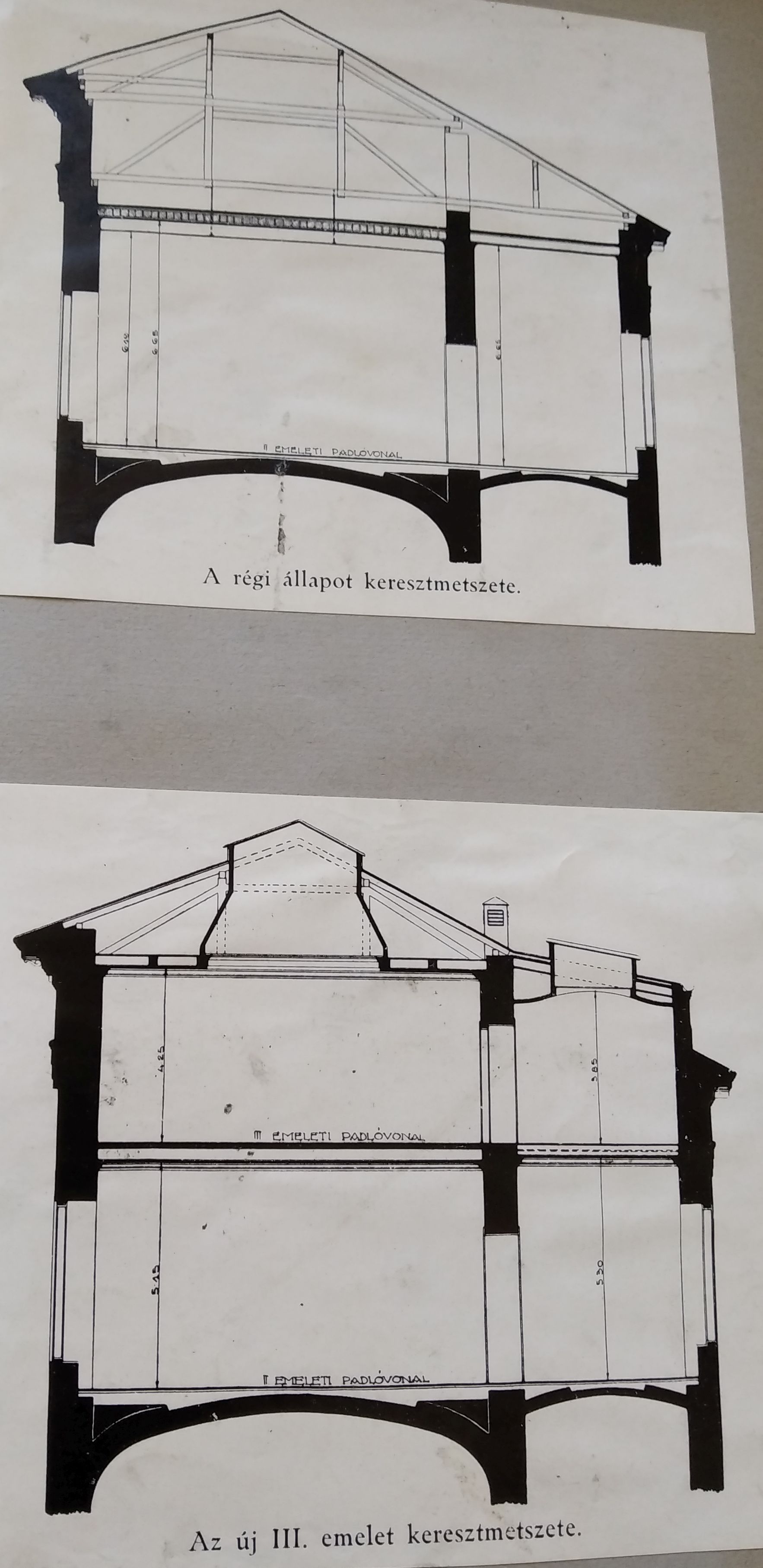

The results of this significant restoration and expansion work were handed over in a ceremony on 22 November 1926. The event was connected with the commemoration of the ten-year anniversary of the death of Franz Joseph, and the museum's collection was also expanded with the monarch's death mask. However, in the following year, further remodelling, or more precisely, expansion work began: a third level, invisible from the outside, was created, the construction of which began in August 1927 and was completed by 1930. A reinforced concrete slab was built into the extremely high second floor, and so that windows did not have to be opened on the facade of the building, the newly created level was lit by skylights. With the exception of the central connecting tract, all wings of the building received a new level, to which three stairs led: one in the rear tract, and two opening next to the dome space.

The section drawings show where the hidden third floor is located (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

This imaginative interior extension brought Jenő Lechner great recognition, even the director of the Louvre admired the new spaces when he visited Budapest. He also wanted to use a similar solution in the museum he managed. But the restoration was also a great success, drawing the government's attention to the classicist style of the reform era. In this, they saw an artistic trend that could give hope to the nation in the difficult times between the two world wars: it reminded people of the rising era of the first half of the 19th century, which they saw as an example to follow.

Cover photo: The Hungarian National Museum around 1879 (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.053)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration