Budapest produced dizzying development in the second half of the 19th century, the population multiplied in a few decades and the number of buildings increased enormously. However, these processes were primarily generated by industry, and thus the changes primarily affected the areas connected to this sector. The cultural sphere, such as education, did not keep up with them either: by the beginning of the 20th century, the lack of schools became acute. For this reason, during the time of Mayor István Bárczy, between 1909 and 1912, the Capital started a large-scale school construction campaign. By the way, the city leader was born on this day 156 years ago.

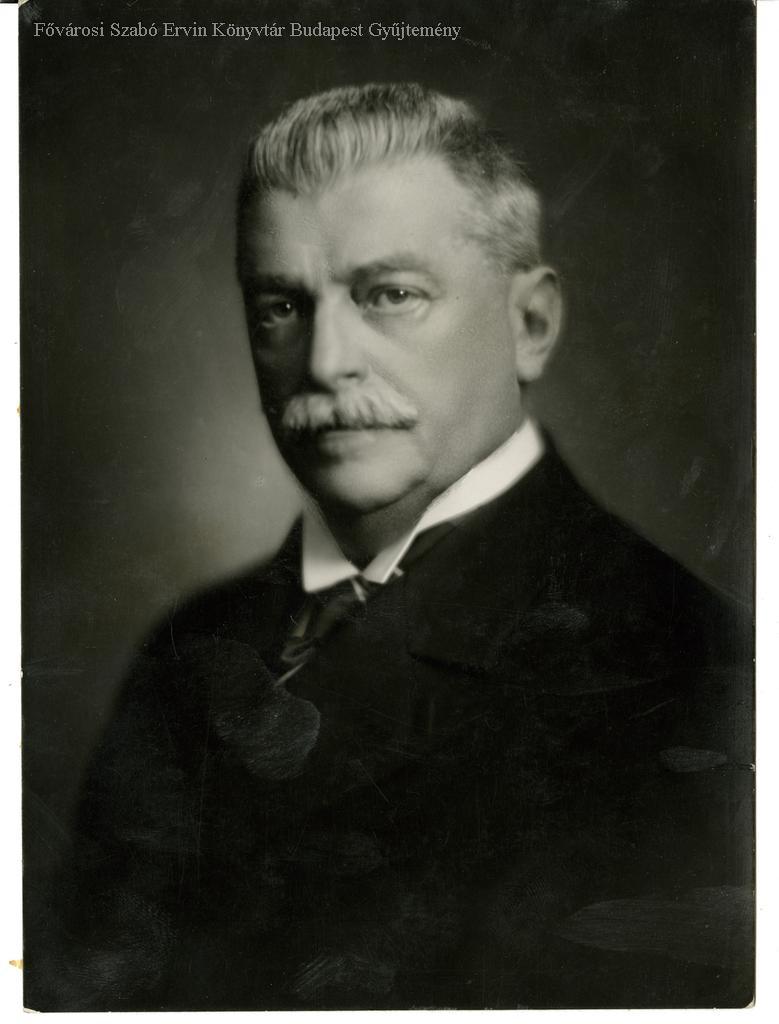

István Bárczy was the mayor of the capital between 1906–1919 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Many educational institutions located in well-known, busy locations were built in these years, for the design of which the capital asked the most excellent architects of the time. The Felsőkereskedelmi Fiúiskola [Upper Commercial Boys' School] in the 8th District, for example, shows the talent of Béla Lajta, who created the jewel of our pre-modern architecture, a pioneering work in Vas Street. In Városmajor, Károly Kós and Dénes Györgyi built the school in their characteristic style, reflecting the Transylvanian folk architecture, and Dezső Zrumeczky's school in Áldás Street is also similar. Today's József Attila Secondary School next to Móricz Zsigmond Square was designed by Gyula Sándy and Ferenc Orbán, Dezső Hültl built a Neo-Baroque school on Mester Street, and Artúr Sebestyén built a Hungarian Art Nouveau school on Egressy Road in Zugló.

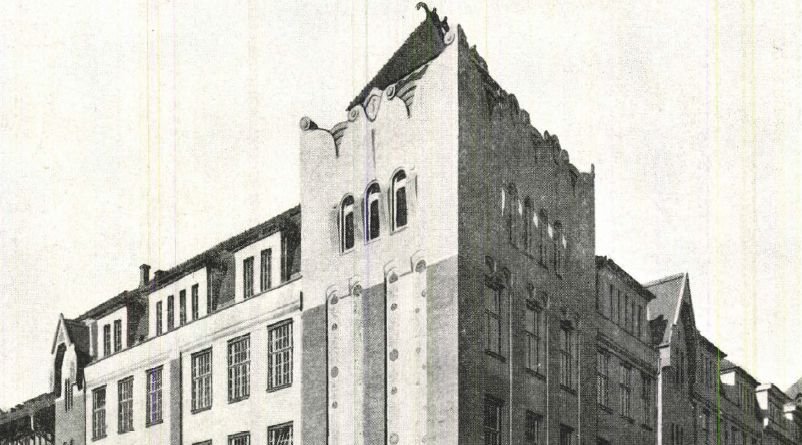

The school in Vas Street is an excellent work by Béla Lajta (Source: BFL_XV_17_d_328_KT_i_130_a, photo by Mór Erdélyi)

In Erzsébetváros, there was also a rather large, empty lot where a school was planned: along Hernád Street, between Elemér (today Marek József) and Dembinszky Streets. The city administration thought that both a boys' and a girls' school could fit here, so they asked Jenő Lechner and Gyula Schmidt D. to prepare the plans. Of course, they coordinated with each other to create a harmonious overall picture, which was bewilderingly successful: only with a very thorough visual inspection can we notice that they are two separate buildings. Today their addresses are 42 Hernád Street and 44 Hernád Street.

The border of the two buildings is marked by the double gutter located in the middle (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

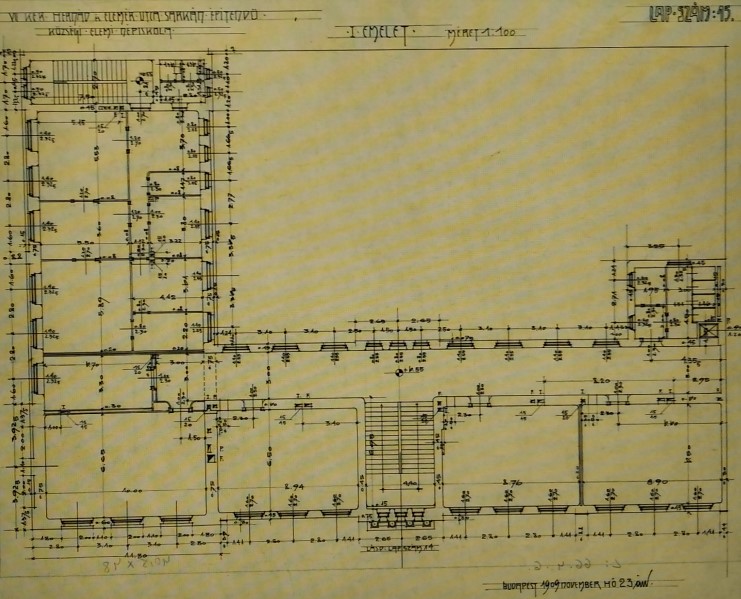

They both planned an L-shaped building for the plot, symmetrical to each other: the longer leg extended along Hernád Street, and the shorter one perpendicular to it, parallel to Elemér and Dembinszky Streets – the former was designed by Jenő Lechner, the latter by Gyula Schmidt D. Of course, their height was also the same, three floors were created above the ground floor in both schools, and in order to increase the capacity, even the roof was made into a mansard so that it could also be used. The regulations had to be met, which determined what kind of rooms the school should include: 17 classrooms, 4 other rooms, 3 supply rooms, a gymnasium with a changing room and an equipment room, a director's office, a council room and a storage room for the faculty, as well as a director's and a servant's apartment.

Floor plan of the building designed by Jenő Lechner (Source: BTM Kiscelli Museum)

The Budapest Engineering Office also determined the dimensions of the rooms: the classrooms had to be 8-10 metres long and 6 metres wide. In the school, the ceiling height was usually 4 metres, the exception being the gymnasium with its 6 metres. Jenő Lechner placed the latter in the basement of the Elemér Street wing, extending it up to the ground floor. There were four classrooms on each level of the Hernád Street tract, of which the ones facing the corner were larger than the others. In the Elemér Street wing above the gymnasium, only smaller rooms were lined up, although two more spacious rooms could be accommodated on the second floor.

The gate of Jenő Lechner's building (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The main entrance in both schools opens in the middle of the facade on Hernád Street and leads to a staircase. There are two classrooms to the right and left of this, which can be accessed from the narrow corridor running from the courtyard side. The architectural framework of the entrances appears to be the same at first glance but on closer inspection, we can observe rather large differences. With Lechner, the gate closes in a so-called segmented arch (circular arch), while with Schmidt, it closes straight. From the side, both gates are surrounded by stones with a rustic surface (roughly worked), on which Lechner placed a tympanum supported by half-columns in such a way that the columns also separate the narrow windows. He placed the coat of arms of the capital city in the middle, on the notched cornice below the columns. In contrast, Schmidt decorated the frame with reliefs of schoolgirls, and incorporated the coat of arms into the pediment above, supported on either side by a lion and a griffin.

The gate of Gyula Schmidt D.'s school (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The large surfaces of the facade are indeed identical: the plinth is covered with stone, the ground floor with brick, and the upper floors with yellow plaster. On the structurally emphasised parts, such as the tower-like blocks placed at the corners and the slightly forward central risalites (protrusions), the proportion of brick is higher: in the former, they extend up to the top of the third floor in strips, while they completely cover the latter. The windows are also the same, their shape is a standing rectangle, and according to the fashion of the time, many dividers divide them into a mesh. On the fourth floor, extending from the tiled mansard roof, there are rows of narrower windows, and these also illuminate the staircase above the main entrance.

The long facade on Hernád Street (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The corner blocks were specially designed to suit their location, mainly Jenő Lechner decorated them with his favourite crenellated Renaissance forms. As the nephew of Ödön Lechner, he was also interested in the Hungarian architectural style, but he tried to create it using a different method: he wanted to further develop an already existing, historical style. Based on his architectural history research, he came to the conclusion that the national character could be discovered in the crenellated Renaissance style popular in the 16-17th century in Upper Hungary, so it was obvious to transform it in accordance with the needs of the 20th century.

The crenellated ending of the corner block (Source: hungaricana.hu)

For this reason, he crowned the corner block with a hipped roof, despite the fact that this was not fashionable in the Renaissance in Upper Hungary. According to his own taste, he also modified the shape of the mouldings, which makes it seem as if the roof is surrounded by a flower: the petals are formed by the individual mouldings, which are made quite fairy-tale-like by their spiral top. He provided the vertical plastered strips on the sides of the block with so-called sgraffito decoration, the essence of which is that the coloured surfaces were scraped back according to certain shapes. In this case, roses with wavy stems and many leaves can be observed, which grow out of vases, and the inscription at the bottom announces the name of the designer and the year of construction. This technique was also very typical of the Renaissance in Upper Hungary.

Sgraffito plant ornaments on the side of the corner block (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Jenő Lechner, like many of his fellow artists, took study trips to Transylvania, and the roof shapes and decorative motifs he saw there inspired him, the result of which can be admired in the pediments of the projections (risalites): he used beautifully carved boards here. He originally decorated them with painted flowers, the shapes of which are the same as the sgraffito plants of the corner block.

The beautifully carved pediment with the original painting (Source: BTM Kiscelli Museum)

Gyula Schmidt D. did not emphasise the corner block in such a spectacular way, he concentrated only on the roof: he made it rather high and with steep sides, which breaks at a definite ledge in the upper third and continues above it at a flatter angle. On its ridge, a wavy-edged end is installed, which further strengthens the vertical direction of the roof. The facade of the block is completely covered in brick, the designer used rustic stones only on the plinth.

The Dembinszky Street corner block designed by Gyula Schmidt D. (Source: Építő Ipar, Issue 17, 1915)

The two schools were built in 1910, and teaching began within their walls the following year. However, during World War I, they were transformed into a military hospital, and after the Treaty of Trianon, refugees were housed in them. Only from 1930 did they gain their original function back. The former boys' school designed by Jenő Lechner now houses the Gábor Baross Primary School, while the neighbour houses the Facultas Human High School. Although they are not the best-known and most original pieces of the large-scale action, they still perfectly show how demanding the cultural policy of the period was and how many different influences affected the architects. They also beautifully reflect how well two designers can work together for a successful result.

Cover photo: The school on the corner of Hernád and the former Elemér Street (Source: Magyar Építőművészt, Issue 11, 1910)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration