Hugó Máltás was born in Rozsnyó in Upper Hungary [now Slovakia] on 6 May 1829, in a Catholic family with nine children. He began his studies in his hometown, then continued in Esztergom and finished at the Benedictine Secondary School in Pozsony [Bratislava]. He purposefully prepared for the architectural career, because even during his high school studies he apprenticed with master builder János Feigl: in the winter he only drew, but in the summer he also took part in constructions.

The Vienna Academy of Fine Arts nowadays, where Hugó Máltás studied (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

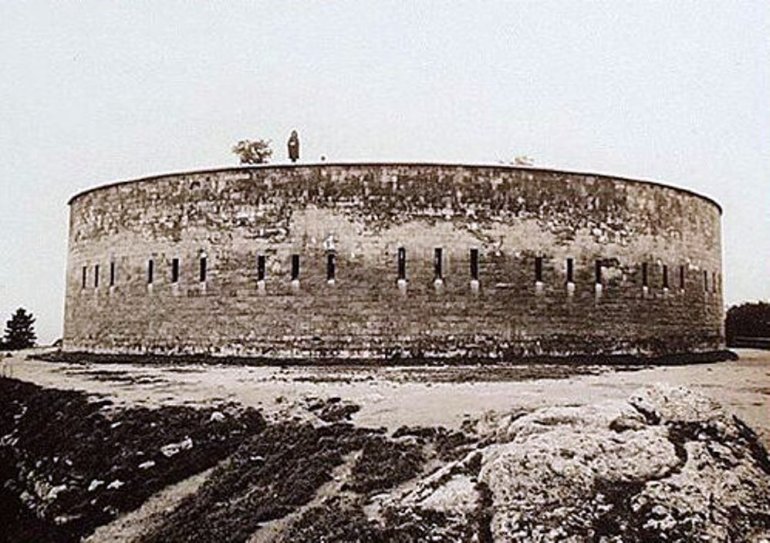

He completed his architectural studies in Vienna between 1844 and 1848 at a very young age. He studied one year at the Polytechnic (the predecessor of today's Technical College), and another three years at the Academy of Fine Arts. In the latter, he excelled under the hands of renowned teachers such as August von Sicardsburg or Eduard van der Nüll, whose names are also associated with the design of the Vienna Opera House. In the fall of 1848, he settled in Pest and worked in the office of Mátyás Zitterbarth. He worked for three years with the famous master of Classicism, who by this time was already past the zenith of his career, as his main works were made before the war of independence. At the beginning of the 1850s, he carried out the foundation works of the Citadel as a contractor, and Máltás may have participated in this huge investment.

The Citadel at the end of the 19th century (Source: OSZK Digital Image Archive, No.: 027687)

His next job was at the National Construction Directorate, where he was employed from August 1851. Here he worked almost all the way on the construction of the Buda Castle, which had to be transformed for the Helytartótanács [Locotenential council] after the defeat of the War of Independence (previously it was used by Palatine Joseph). So this was not yet connected to the large-scale expansion taking place at the end of the century and was on a much smaller scale. But Máltás himself did not really delve into it either, because after only two years, in August 1853, he left the Directorate in order to teach as a drawing teacher at the Buda city drawing school. Although this involved a more modest financial appreciation, he was finally able to plan independently.

He was not idle either, he received commissions one after the other, some of which were due to his good relationship with the Buda city council (the maintainer of the drawing school). At the beginning of 1854, he drew up a plan for the reconstruction of the main facade of the Church of the Assumption (commonly known as Mátyás Church), which unfortunately did not survive, but from descriptions, it can be seen that it contained two towers and would have reflected Máltás's own idea of the Middle Ages, had it been realised. However, this did not happen, instead, Frigyes Schulek rebuilt the church in the last quarter of the century. Also left on paper was the floor extension plan for the old Buda town hall opposite the church.

Reconstruction of the Church of the Assumption (Source: Fortepan/No.: 116770)

The apartment building at 38 Úri Street, on the other hand, was raised by one level and its interior was remodelled according to his plans. Máltás designed a Gothic-Romantic facade, which was the defining style of the 1850s. Compared to the Classicism that preceded it and the historicism that followed it, it was in fashion for a very short time, and as a result, relatively few architectural memories of romanticism have survived. Basically, two trends can be distinguished: the semicircular and the peaked, which primarily refers to the shape of door and window openings. Both refer back to the Middle Ages, not by faithfully following Romanesque or Gothic architecture, but merely by evoking its atmosphere. In Máltás' work, the semicircular version is much more common, and peak arches were rarely designed. On the other hand, another characteristic feature of the style came to the fore in the Úri Street house: the ornamental decoration of the window aprons. Plant tendrils can also be seen above the openings with straight closures and on top of the hood mouldings.

Residential building at 38 Úri Street in the Castle (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

At the foot of the Buda Castle, in the residential building at 18 Hunyadi János Road, the semicircular trend can already be recognised, as the windows on the first floor show this shape. Here, too, their arches are surrounded by a strong cornice, and plant tendril motifs are also present in the aprons. The protrusion from the centre of the facade, on the other hand, is closed by a triangular gable, which is broken by a triple-pane linked window. This is not really characteristic of the style of Máltás, it presumably reflects the wishes of the builder, Ferenc Reitter. He also understood architecture, as he was the chief engineer of the National Construction Directorate in Buda, who, among other things, planned the regulation of the Pest side of the Danube and the construction of the embankment.

Ferenc Reitter's former house at 18 Hunyadi János Road (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

In 1855, Hugó Máltás was asked to design the pedestal of the Holy Trinity Statue in Zsigmond Square. The work was made in the Baroque style at the beginning of the 18th century and originally stood on Szentháromság Square in the Castle, but a few decades later it was moved to Újlak, which is part of Óbuda so that the sculpture group known today can be put to its place. In the middle of the 19th century, the restoration of the statue became relevant, but the pedestal was already unsalvageable, so Máltás designed a new one instead. In the same year, he also worked on the new building of the Budai Reáliskola [Scientific Secondary School of Buda], at the request of the city council he made drawings for it, but in the end, they were not realised, the school was built according to the plans of Hans Petschnig.

The residential house of the Zitterbarth Family at 22 Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Road (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

His first work on the Pest side of the capital was a residential house at today's 22 Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Road, which is also called the Zitterbarth House after its builders. His relationship with his former boss certainly played a role in the invitation to design. In fact, on the plan itself submitted for approval, the signature of Mátyás Zitterbarth Jr. is included, as Máltás did not have guild master rights. Only the three-pane entrance of the building, which was completed in 1857, fits the romanticism we have seen so far, the design appearing on the floors - especially the broken-line hood mouldings of the windows - is closer to the Baroque. The details of the five-axis main facade are also very rich, for example, the wall pillars delimiting the central risalit were also given a decorative capital. The residential house was originally a three-storey building, the fourth one visible today was added afterwards. Unfortunately, its gate no longer shows the image it had when it was handed over, which was once like a hall and an arcaded corridor led to the inner courtyard.

The Jégverem Street and Fő Street facade of the Masjon Family's residential house (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

He designed an even larger residential house at 2 Jégverem Street in Buda on behalf of the Masjon Family of Dutch origin in 1861. Three of its facades are free-standing, so its size seems even larger: one faces the Danube bank (4 Bem Embankment), another faces Fő Street (number 7), and the third faces Jégverem Street. If we take a closer look, however, we can see that it has two entrances, as the unified exterior hides two separate apartment buildings. It does not have the vibrant decorations of the Zitterbarth House, but the elegant restraint befits a building of this size anyway. Romantic elements can be found around the windows: tendril aprons and hood mouldings.

The largest building of Máltás is the Kovács-Sebestyén House on József Nádor Square (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The largest creation of Máltás - both in terms of size and quality - is the Kovács-Sebestyén House at 5-6 József Nádor Square. The client was Endre Kovács-Sebestyén, a surgeon at the Rókus Hospital, who decided to build a residential house on this renowned site for investment purposes. The eponymous palatine wanted to make the formerly irregularly shaped square the centre of the developing Lipótváros, so even during the Reform era, its contours were arranged and several classicist palaces were built here. Máltás, on the other hand, created the plans in a romantic style in 1860-1861, but despite the fact that he also used Baroque elements, the facade creates a calm, balanced, monumental effect, so it is not foreign to the overall image of the square. In any case, he concentrated the Romantic-Baroque decorations on the corner risalits (protrusions) - which are connected by huge wall pillars - the middle sections are less articulated. It was originally a three-storey house, during 1922-23 the Magyar Forgalmi Bank [Hungarian Commercial Bank] expanded it with another level, which is how it acquired its present appearance.

There was a water pump in the house at 3 Fő Street (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The building erected at 3 Fő Street in Buda is similar in style to the previous one, but its function is quite special: it was a water-pump engine room and residential house. The machines designed by Ádám Clark brought the water up to the Castle, in the tank next to the Castle Theatre, for which Máltás designed an architectural framework between 1861-1866. A steam engine was used to operate the powerful pump, and it was accompanied by a tall chimney that stretched from the narrow courtyard of the house towards the sky. The industrial building stands in strong contrast with the detailed, Romantic facade. In particular, the semicircular windows on the first floor are surrounded by Moorish decorations.

From the end of the 1860s, public taste changed and romanticism was replaced by the Neo-Renaissance. In this, Máltás felt less at home and his buildings did not represent such a high standard, but they were decently solved works. Most of them are schools that were built in the capital under a regulated program. At first, architect Alajos Vassél received the design commissions, after his death Frigyes Feszl and his nephew, László Feszl, and then Hugó Máltás designed most of the schools. In 1869, he designed the Krisztinaváros Teacher Training School, which was located at 97-99 Attila Road, and between 1874 and 1875 the Medve Street school was built according to his plans (5-7 Medve Street) and today, the Csik Ferenc Primary and Secondary School operates there.

The Csik Ferenc Primary and Secondary School today (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

His last work was realised in a symbolic place, in the Kerepesi Road Graveyard (today Fiumei Road National Graveyard): a mortuary and funeral home, built in 1879-1880. After that, he also took part in construction matters, but only as a clerk, in 1874 he became the construction officer engineer of the newly established Technical Department of Budapest. He spent nearly three decades in this position until he retired in 1901. He remained mentally fresh even after that, so unfortunately he also had to see the country fall apart because of the Treaty of Trianon. He died on 4 June 1922, the second anniversary of the tragic peace treaty.

Cover photo: The Kovács-Sebestyén House on József Nádor Square (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration