- How did you join the team that has been working on the recreation of the Palace, which also includes St. Stephen's Hall, for many years now?

- Apparently by accident, yet I think every turn in my life took me to participate. There was some sort of destiny in this. I was attracted to this story as a child, I always knew that the Royal Palace we see now is just a caricature, a torso of the original.

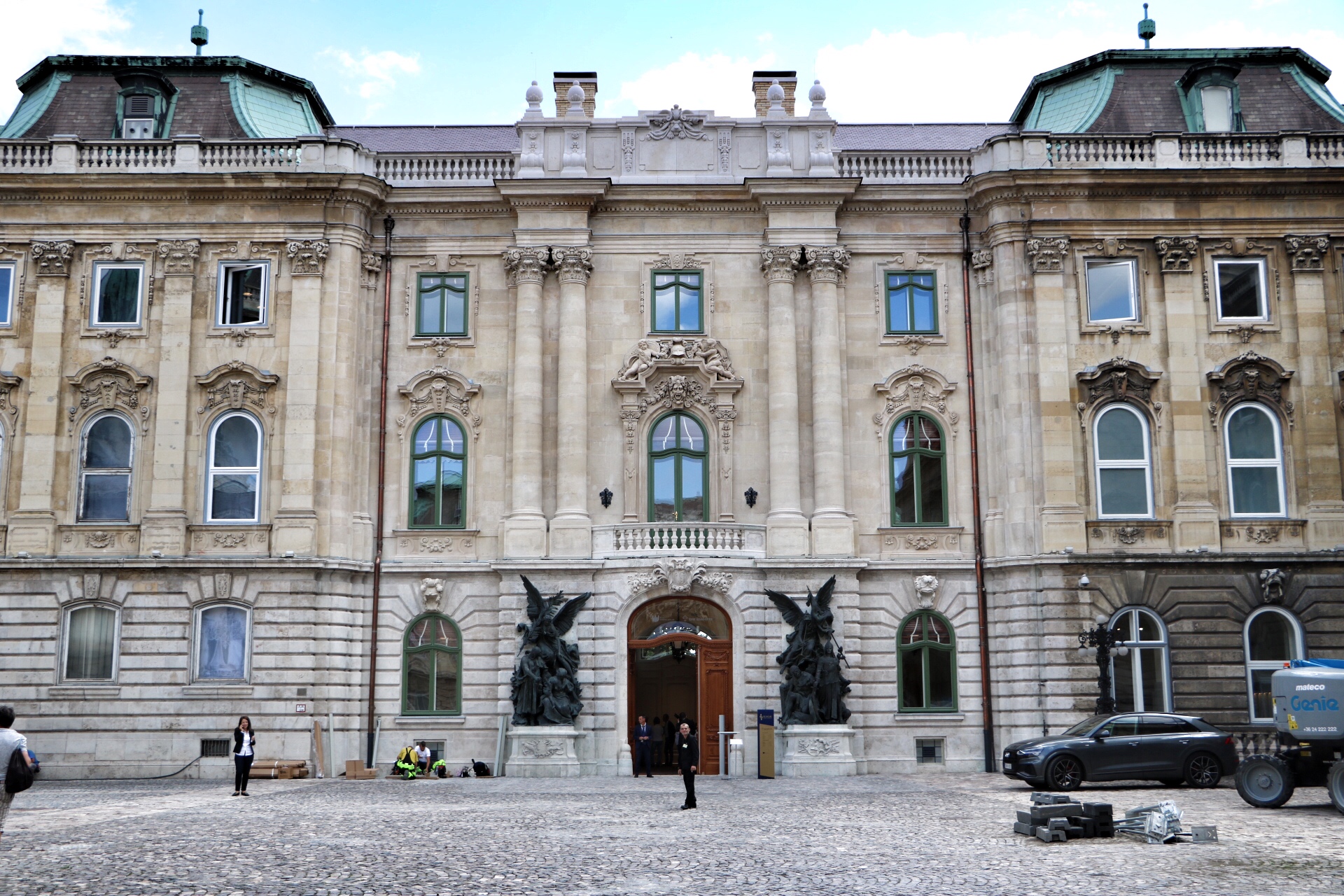

The re-created southern connecting wing, which opens on 20 August, has the St. Stephen's Hall on the first floor (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

The re-created southern connecting wing, which opens on 20 August, has the St. Stephen's Hall on the first floor (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– How did you know?

– I do not remember how I found out, but I do know that my sister, who was in school at the time, had a history booklet with the original Royal Palace on the cover, which I detached from her booklet against her will, which she rightly objected to. I was fourteen at the dawn of the regime change when I wanted to persuade my family to buy a mansion: we looked at many, but in the end, unfortunately, did not buy any, so I decided to plan one for myself. I kept drawing the castle of my dreams, walking around it at night.

– You presumably took great advantage of your drawing mania at the Faculty of Architecture of the Budapest University of Technology and Economics.

– Interestingly not. I also thought it was an advantage to draw castles in a historical style, but no, the instructors hated it. After four years, I left the university, then after seven years I enrolled again and started all over, finally graduating in 2011.

Every detail of the St. Stephen's Hall had to be redrawn (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

Every detail of the St. Stephen's Hall had to be redrawn (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– By then, several concepts had already been made about the transformation of the palace. Have you ever wondered if you could participate in this in any way?

– I would not have thought of it in my dreams, but the history of the palace has always interested me. I was in my 4th year at Budapest University of Technology and Economics when I went to Tamás Mezős, who was the president of the National Office of Cultural Heritage at the time and asked him what data was available about the Royal Palace and what can be done with it. He said he thought the row of halls could be made, including the St. Stephen's Hall. Back then when I was a college student this opportunity seemed so distant. I was there in 2011 at the presentation where architect Ferenc Potzner showed the development concept plan of the palace, which laid the foundation for the whole reconstruction. It did not even occur to me then that I could have something to do with this, and I could work with him as well, since he is the lead designer for this southern palace wing we are talking about right now.

Architect Tibor Angyal in the St. Stephen's Hall, in front of the Zsolnay fireplace (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

Architect Tibor Angyal in the St. Stephen's Hall, in front of the Zsolnay fireplace (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– When you graduated from university, why did not you work as an architect?

– I could not find a job, I did not know what to do, so I settled at the Forster Centre, the successor to the Office of Cultural Heritage. Due to lack of space, I had a desk in the Photo Gallery, but I did not draw, among others, I had to translate the Romanian, Serbian, Ukrainian monument lists with Google and organise them into Excel spreadsheets. Before that, I carried boxes and furniture in the moving Hungarian Museum of Architecture with collection manager Pál Ritoók.

– And suddenly a door opened, in a real and symbolic sense as well.

– Indeed, in the fall of 2015, art historian Dr Péter Rostás entered the Photo Gallery of the Forster Centre to research there, he had been dealing with the interior of the St. Stephen's Hall for many years and was the initiator of its recreation. I was arranging the exciting Excel spreadsheets in the other room, but the conversation filtered through, I heard it was about the Royal Palace. I immediately went over and mingled in conversation with him, even though I did not even know who he was.

Tibor Angyal already knew as a child that what can be seen from the Buda Castle is only a torso of the original. The picture shows the re-created St. Stephen's Hall (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

Tibor Angyal already knew as a child that what can be seen from the Buda Castle is only a torso of the original. The picture shows the re-created St. Stephen's Hall (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– You have not had too much architectural duties until then. How did this become an assignment?

– Until then, I had only one architect's assignment, namely, to design new gratings for the pavilion hiding the statue of St. John of Nepomuk in Csepel, and then to design a small stone bridge next to it. But from 2015, everything changed, and the conversations with Péter Rostás ended with the fact that I was commissioned to redesign the St. Stephen's Hall, as he was responsible for the reconstruction of the hall. Back then, we both thought it could be done in three months. The plan was that I am making drawings and someone else will do the three-dimensional versions, but then I ended up doing all the work, I worked on it day and night for six years.

– But how did it turn out that it was worth entrusting you to the redesign, because from now on you will draw day and night?

– I have no idea why I got the job. Maybe because I was proactive.

– What did this mean in practice?

– At that time, the reconstruction of the Riding Hall, the Guard House and the Stöckl-stairs was already in progress. The Stöckl staircase had a stone chest with a wrought iron insert at the level of the Hunyadi Court. When I looked at the old photographs in the Photo Gallery, I realised that it was exactly like the parapet or railing of the turul gate opposite the Sándor Palace. At times, during working hours, I slammed a large cardboard under my arm like a homeless person, escaped from the Forster Centre on Táncsics Street with a camera, went to the gate, put the cardboard behind it to contrast, and drew, photographed it without an order, and I showed this to Péter Rostás. This is how our cooperation began.

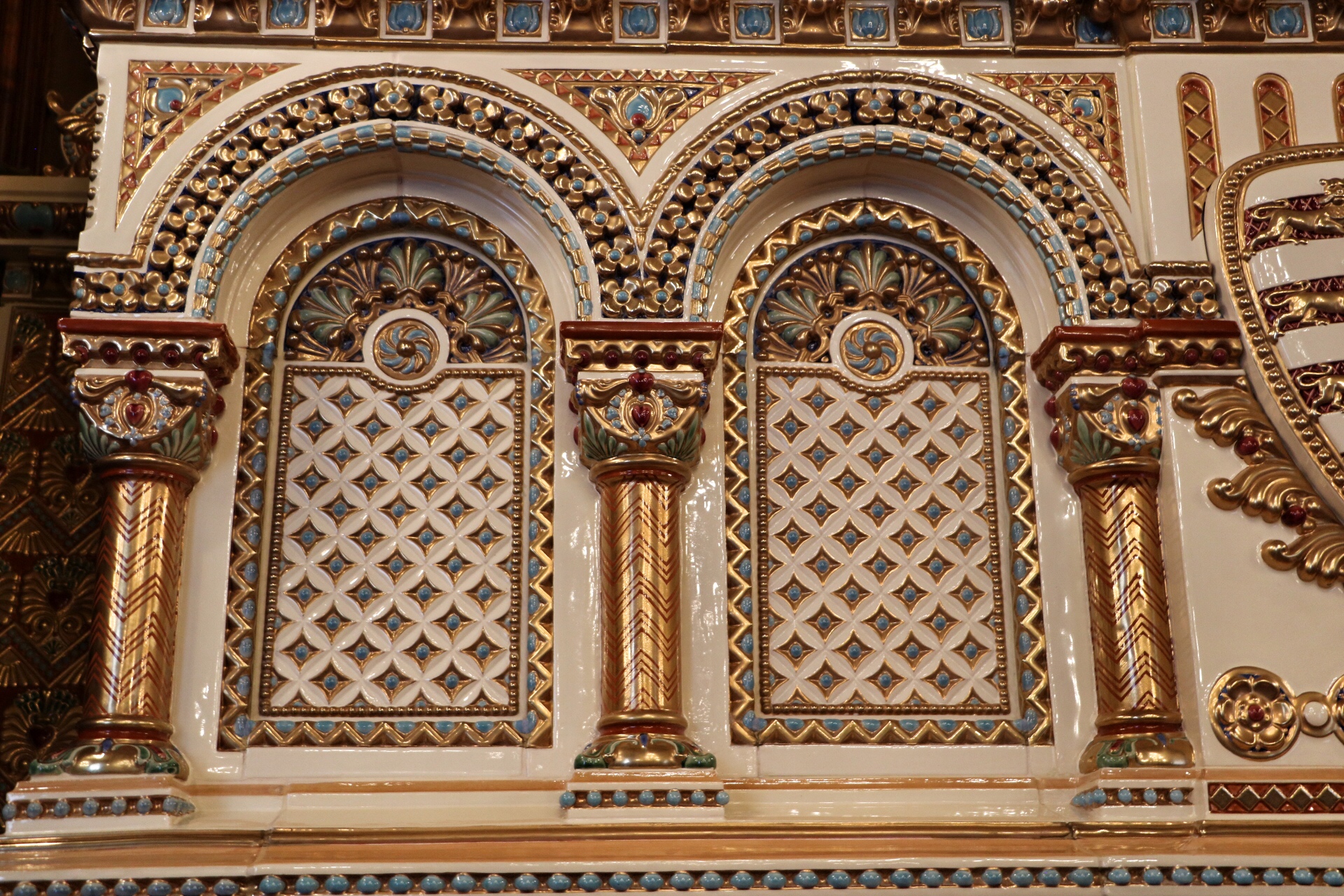

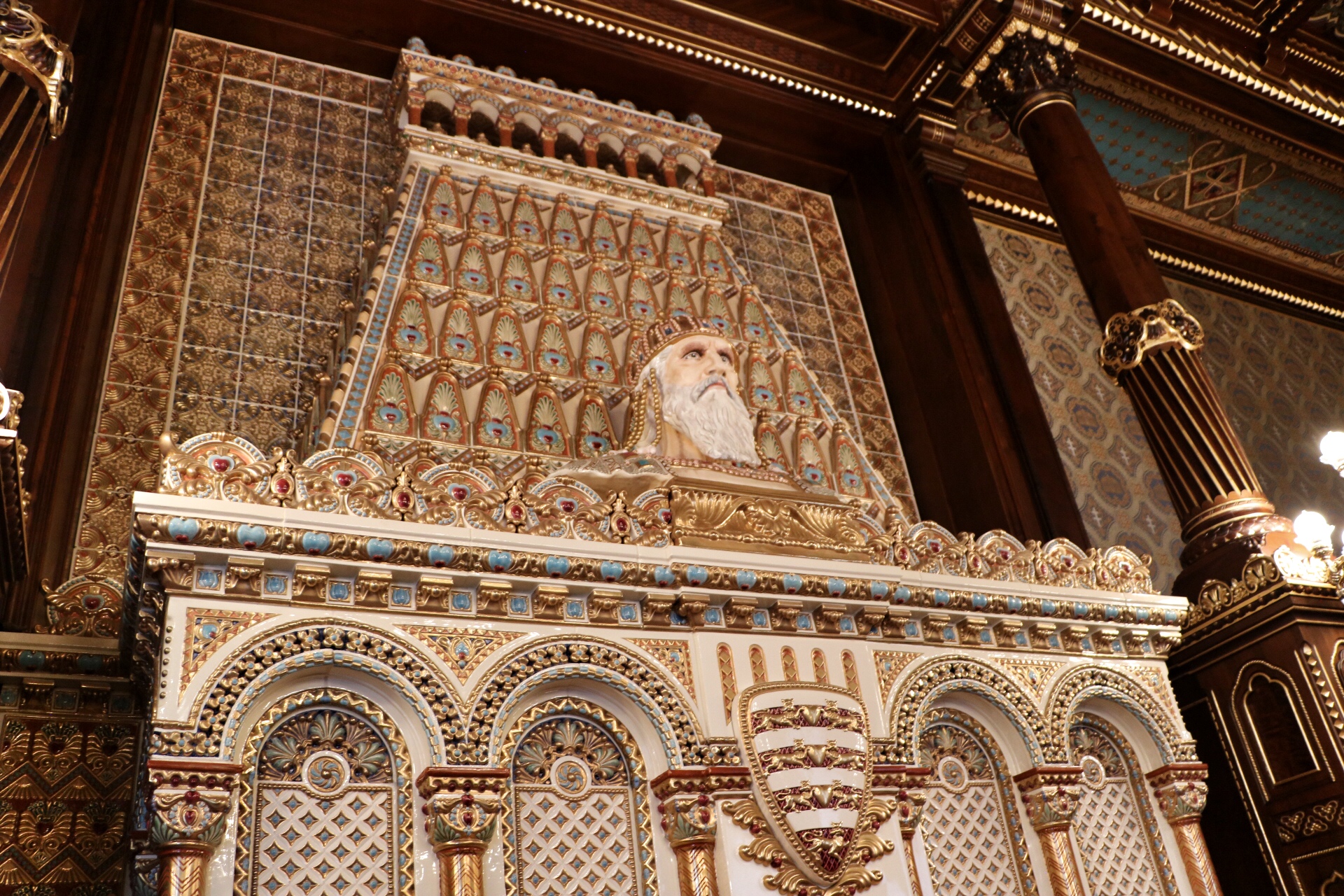

“We thought it could be done in three months,” says Tibor Angyal. The picture shows a detail of the Zsolnay fireplace (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

“We thought it could be done in three months,” says Tibor Angyal. The picture shows a detail of the Zsolnay fireplace (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– Six years ago, why was it assumed that redesign tasks could be completed in three months?

– It was an era of naive surprises, we thought that I will draw it and it will be done. I got a good few high quality archive images; they helped a lot. I also visited the Janus Pannonius Museum in Pécs, where I have some test pieces of the fireplace, small pieces, and test specimens of ceramic kings. There in the museum, they said they still had some plans: they will scan and send them.

– What did you know about the hall when you started drawing?

– We did not know any size, just the size of the enclosure from wall to wall, without cladding. There were some large, incomplete plans for the fireplace with one or two basic sizes, but in many places with details different from the realised version. From the door leaf as well, but also with different sizes and different decorations. Neither original designs nor original pieces could be blindly trusted, so much was changing during the planning. Therefore, I started drawing mainly based on photographs, because only what appeared in the photos could be considered certain, as it was real at some point in time. I have been already planning a lot when the promised plans arrived from Pécs, three or four pages with scaled wall views here and there. And then, after three months, I thought that my role is over, here are the original plans, this just needs to be redrawn and built. Then it soon became clear that this did not depict the St. Stephen's Hall that we know.

Let us not be more Hauszmann than Hauszmann - confesses Tibor Angyal (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

Let us not be more Hauszmann than Hauszmann - confesses Tibor Angyal (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– Was it an earlier version of the plan?

– Yes, the drawings came from 1898, they were made with ink, they have a seal, stamp, document stamp and signature from Alajos Hauszmann, Frigyes Podmaniczky, Vilmos Zsolnay, but it was not built exactly like that. Originally, Vilmos Zsolnay initiated to have a Zsolnay hall in the palace, but the plan was constantly evolving and evolving. I also saw a version from the end of the 19th century depicting a fully Art Nouveau style St. Stephen's Hall, to the right and left of the fireplace were the same three images each, opposite a mirror wall, triplets above the door, but there was no signature on the drawing, so we do not know who made it. The final version of the hall has some Zsolnay in it, but with restraint - if a 4.7-metre-high fireplace can be called restraint.

– How did the room proposed by Vilmos Zsolnay become a ceremonial hall reminiscent of the glorious period of Hungarian history, the age of the Árpáds?

– I have a theory for this. The homage to the Habsburg House appeared at several points in the palace, as it was a monarchy, and the expansion of the palace could be accomplished at the mercy of the Habsburgs. On the Danube side, the ornate staircase was called the Habsburg Staircase, above it in the tympanum was the glorification of the Habsburg House, behind the stairs on the first floor, the room under the dome was called the Habsburg Hall. The ceiling fresco depicted the deification of Franz Joseph and Elisabeth, there are monograms of Franz Joseph in many places, and then Hauszmann might have thought that there should be something national in the palace. There is on the main facade facing the Danube that frigid Habsburg Hall, let us give the emperor what belongs to the emperor, but let us do a little further back, two Hungarian themes: one became the St. Stephen's Hall and the other the Matthias Corvinus Hall.

Images of kings and saints of the Árpád House decorate St. Stephen's Hall (Photo: Júlia Kozics / pestbuda.hu)

Images of kings and saints of the Árpád House decorate St. Stephen's Hall (Photo: Júlia Kozics / pestbuda.hu)

– Of the three historical ceremonial halls, why do we feel St. Stephen's Hall to be the most special?

– Hauszmann himself wrote in his article about the palace that he wanted to see not only the motifs of classical historicist architecture in the building, but also Hungarian elements, Hungarian decorations, and the works of Hungarian craftsmen. Such was the St. Stephen's Hall. It feels like it is all done with love. 72 square metres - the medium halls are on this scale in the palace, but it shows that everything was given in, let it be ours, let it be real. It is no coincidence that one of the most important motifs is the heart: we find hundreds of hearts in the hall. Alajos Hauszmann decided what the room should look like, but he mentions in an article that his colleague, Géza Györgyi drew “all the details of the room”.

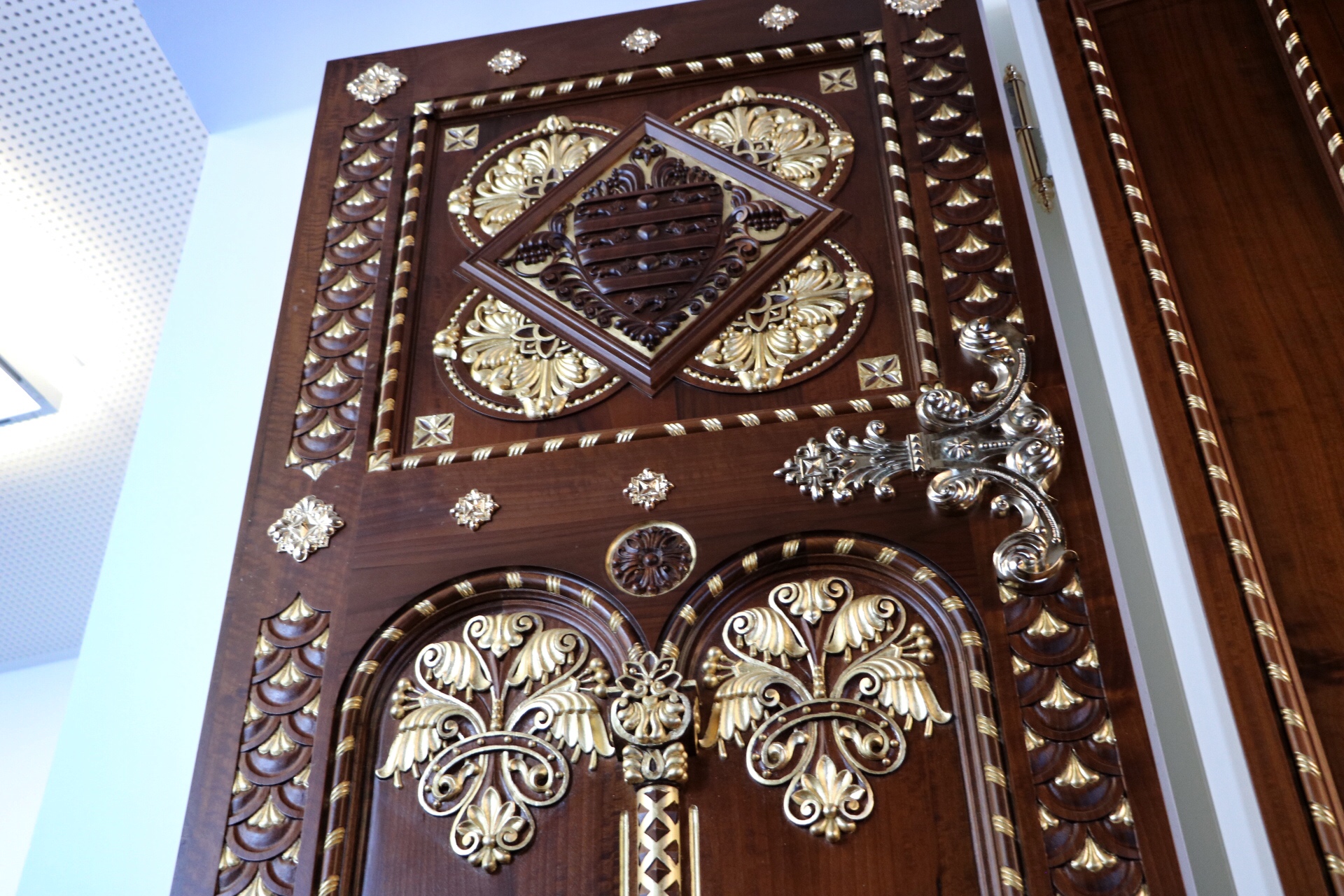

The walnut doors with the gilded bronze fittings and handles, one of which, when turned vertically upwards, elegantly release the bar lock of the secondary wing, as it once did (Photo: Júlia Kozics / pestbuda.hu)

The walnut doors with the gilded bronze fittings and handles, one of which, when turned vertically upwards, elegantly release the bar lock of the secondary wing, as it once did (Photo: Júlia Kozics / pestbuda.hu)

– Now, when you redrawn the same motifs that Géza Györgyi drew under Hauszmann's direction, can the specific style of the designer be perceived?

– Yes, it can be. Hauszmann ran a large architectural firm and there were countless talented people around him. One can feel the differences between them if we look at the different parts of the palace, the dome, the riding stables. Géza Györgyi reveals from his work that he was a brilliant man. He had the ability to create ornamentation and the ability to draw that not many architects had, I think he drew most of the palace ornaments. He poured the drawings out of himself.

On the guided tour, the shutter boards usually hidden behind the silk curtain with the handle of the original, round Vágó rod lock, and with the hinges consisting of an even number of segments, which are no longer common today (Photo: Júlia Kozics / pestbuda.hu)

On the guided tour, the shutter boards usually hidden behind the silk curtain with the handle of the original, round Vágó rod lock, and with the hinges consisting of an even number of segments, which are no longer common today (Photo: Júlia Kozics / pestbuda.hu)

– What caused the greatest difficulty in the redesign of St. Stephen's Hall?

– There is a law enforcement saying: the persecuted has a thousand ways, but the persecutor has only one: the right clue. I followed that clue. Based on excellent photos, I had to redraw every square inch of St. Stephen’s Hall, but in two places I could not perfectly identify the original patterns. There are recesses on each side of the fireplace, where the large tile tilts obliquely inwards and the images either show only the edges or glitter or are so dark that it is not possible to take out the motifs properly, only the outlines of the sculpture. I thought about these for years while the rest of the fireplace was being made, hoping until the last minute to see if a better photo or a good idea would come up. Respectively, above the fireplace, there is a carving on the beam that also only shows pieces. You can know roughly how detailed it is, but the details cannot be taken out. I designed the decoration for these places from motifs taken from the rest of the room, which was pretty much in my hands by then. In the other places, every berry and leaf could be counted and read from the photos.

Based on the black and white photos, the location of each colour was easily identifiable (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

Based on the black and white photos, the location of each colour was easily identifiable (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– From the black and white photos. But how did you identify the colours? How did black and white images become a colourful interior?

– It was an interesting task, especially for the fireplace, which has a lot of colours. Using the principle of wavelength-selective light-sensing of contemporary black-and-white photographic raw material, we were able to figure out in which place what colours were. In this work, my partner was Boglárka Szentirmai, a painter-restorer, architect, monument engineer, with whom we had previously filled out the Excel spreadsheets with a Google translator at a table, and I also received the large checkered booklet in which I had drawn everything by hand over the years. Contemporary ceramic specimens and duplicates have survived in the museum in Pécs, and even built into a wall elsewhere, although in many different colour variations, so it was necessary to determine which one can be seen in the old pictures. There are several pieces of the excess of the original tapestry, and one of the original curtains rescued from the hall during the war has also survived.

.jpg) The colour scheme of the northern wall (left) and the ceiling (right), a joint work of Tibor Angyal and Boglárka Szentirmai

The colour scheme of the northern wall (left) and the ceiling (right), a joint work of Tibor Angyal and Boglárka Szentirmai

– Hauszmann fought for the palace to be decorated with works by Hungarian masters. And now?

– At that time, some of the embroidered textiles were probably made abroad, this is still the case, they were made in Berlin, Munich and Lyon, the rest are still Hungarian, as then.

– It has been 120 years since then, there has been a technological change, to what extent has it affected the restoration?

– The visible parts are still made of the same material as 120 years ago, everything is authentic, there is nothing in the material and technology of the visible parts that would be worse. After the manual sketches, I drew with a computer, actually with software not designed for that, but with that, I had complete control over every millimetre of lines, there was nothing mechanised, the drawing was more manual. I also realised that at the time, everything was not rigidly perfect, uniform, symmetrical, or accurate. It was more human. Therefore, I did not correct any contingencies, but designed everything as it appears in the photographs. My saying is: let us not be more Hauszmann than Hauszmann.

Only one archival photo of the mirror wall and the console table has survived for redesign (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

Only one archival photo of the mirror wall and the console table has survived for redesign (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– And if you now stop in the middle of St. Stephen's Hall and look around, are you satisfied with the result?

– I feel like we have got everything we can out of it. We followed everything to the maximum. What we thought needed to be repaired was repaired, remanufactured. Fortunately, we were also supported by the customer, the Várkapitányság. It was also important for us not to compromise too much.

– What did those who had to make the ordered product twice or even more say?

– There have been very few people working on redesigning the room who have seen this work as a mere business. There were quite a few, however, who, to their insanity, strived to make everything authentic. Repeatedly, they voluntarily made the elements they had already made to make it even better, because they did not look at material gain, but at making it perfect. I was in the apartment of my colleague Ádám Vecsey, a metal restorer who also made chandeliers, where almost everything was covered with gilded metal objects related to the room, even on the windowsill, and I do not know how many times he said to me, “You listen, I realised I can do something better, I saw something similar somewhere, I will do it again". Of course, others hated me, but I would rather them to hate me than look at the imperfect hall for years after that. They did not hate me so much because, for example, the building carpenters gave me a gift after finishing the hall, and invited me to a weekend in Hortobágy, even though I broke it down with them many times, which was not good.

Tibor Angyal: "There were quite a few [ed.: people], however, who, to their insanity, strived to make everything authentic." (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

Tibor Angyal: "There were quite a few [ed.: people], however, who, to their insanity, strived to make everything authentic." (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– Do you think this work has become a passion of these participants?

– It has become completely our passion. My art historian colleague, Péter Rostás, and I often looked at berries for hours, guessing that there are 3 berries or 4 berries in the design, a leaf wrapped to the right or to the left. We often talked until midnight, and when a photo or some other data came up, we rethought the whole thing, convincing all the participants to do everything again to be authentic.

With another colleague of mine, Tamás Szegő, whom we used to work at the site visits, we also talked many times until midnight after the daily work on how to interpret the plans of the royal palace, for example, about the radiator cover. We had to fully immerse ourselves in the data, the invoices, the plans, understand what we could deduce from them, figure out how they thought, what was the usual design and construction system, so that we could follow the technical solutions as faithfully as possible, what were the things they did not do, what they used to do. It was mania, it could not be done otherwise. That is why we could make the door lock, the window hardware, the pulling cord with hangman's knot-copper ring, and the special shutter lock until the last screw as it was.

The windows of the Hauszmann period were very complicated structures (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

The windows of the Hauszmann period were very complicated structures (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– The mania is rumoured to have been in you, because if you had to, you made a GIF animation or salt dough pottery to show what to make.

– There have been stories like this, yes, I put a lot of energy into passing on the right information. In Zsolnay, quite young boys and girls modelled, worked incredibly nicely on 120-year-old forms, but there was an element that had a heart in it and did not want to come together. Its photo was sent to me, and I marked the parts which I did not like, or redraw it with Photoshop. I also created a GIF animation out of it. In another case, I ended up making salt dough pottery to be able to show what to make. Luckily there was flour at home, I designed it, baked it in the oven at night, and I took it to Pécs the next day, and then they could work based on the sample.

– You redesigned every detail of St. Stephen's Hall, and then followed every phase of the re-creation. What exactly?

– Inspection of works in production workshops during manufacturing. Sometimes I had to draw a wavy decorative sample on a piece of the fireplace, or carving a sample on the door, making some special cuts on the corner posts. In the last weeks of the installation, I was often out in the hall from morning to dawn, also on weekends. At first, I only dealt with St. Stephen's Hall, but later I worked on the Neo-Renaissance corridor next to it, which I eventually completely redrawn and oversaw. I also drew the chandelier in the hall based on photographs, and in the south connecting wing all the parquet floors and all the historic doors and windows with shutters and radiator cladding, grilles, except for the large oak gate next to the hall, which is the excellent work of my colleague Kornél Baliga.

The windows of the southern connecting wing were also designed by Tibor Angyal (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

The windows of the southern connecting wing were also designed by Tibor Angyal (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– What is worth knowing about Hauszmann windows?

– The windows were quite complicated structures. These are traditional double casement windows, but in addition to the shutter panels, there were also two shading structures between the two sash windows, a wooden lamella blinds called a Roman shutter or plank shutter, was outside. And inside, but still between the two sashes, there was a canvas that could be pulled up. The bottom of the canvas, the bottom 15 centimetres, is made of lace. I noticed this at the last minute. Since then, it turned out that in many places in the palace it was like this on the windows, and even in an old picture in Fortepan, one of our textile colleagues found it in the window of a villa, from where it could be edited back. So maybe it could have been some kind of ready-made product.

The walnut window structure with the original door handle, hinge, and the archaic, rotating shaft lock, the lace blinds between the wings, behind it the characteristic plank shutter (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

The walnut window structure with the original door handle, hinge, and the archaic, rotating shaft lock, the lace blinds between the wings, behind it the characteristic plank shutter (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– In other cases, did it happen that non-unique products were made for the palace?

– In several cases, it turned out that confectionery products were also used in the construction of the palace. The firepot of the fireplaces outside of St. Stephen's Hall, for example, was covered with an embossed cast iron plate with a characteristic design, which I recognised this in Alajos Hauszmann own Venetian castle when I snuck in. Nor was everything individually designed for St. Stephen's Hall. There, the floor of the fireplace was laid out of 12x12 cm unglazed tiles, it is also Zsolnay ceramic, I recognised it on the firepot floor of the castle of Nádasdladány, Hauszmann also worked there.

– Has there been any other surprises during these six years?

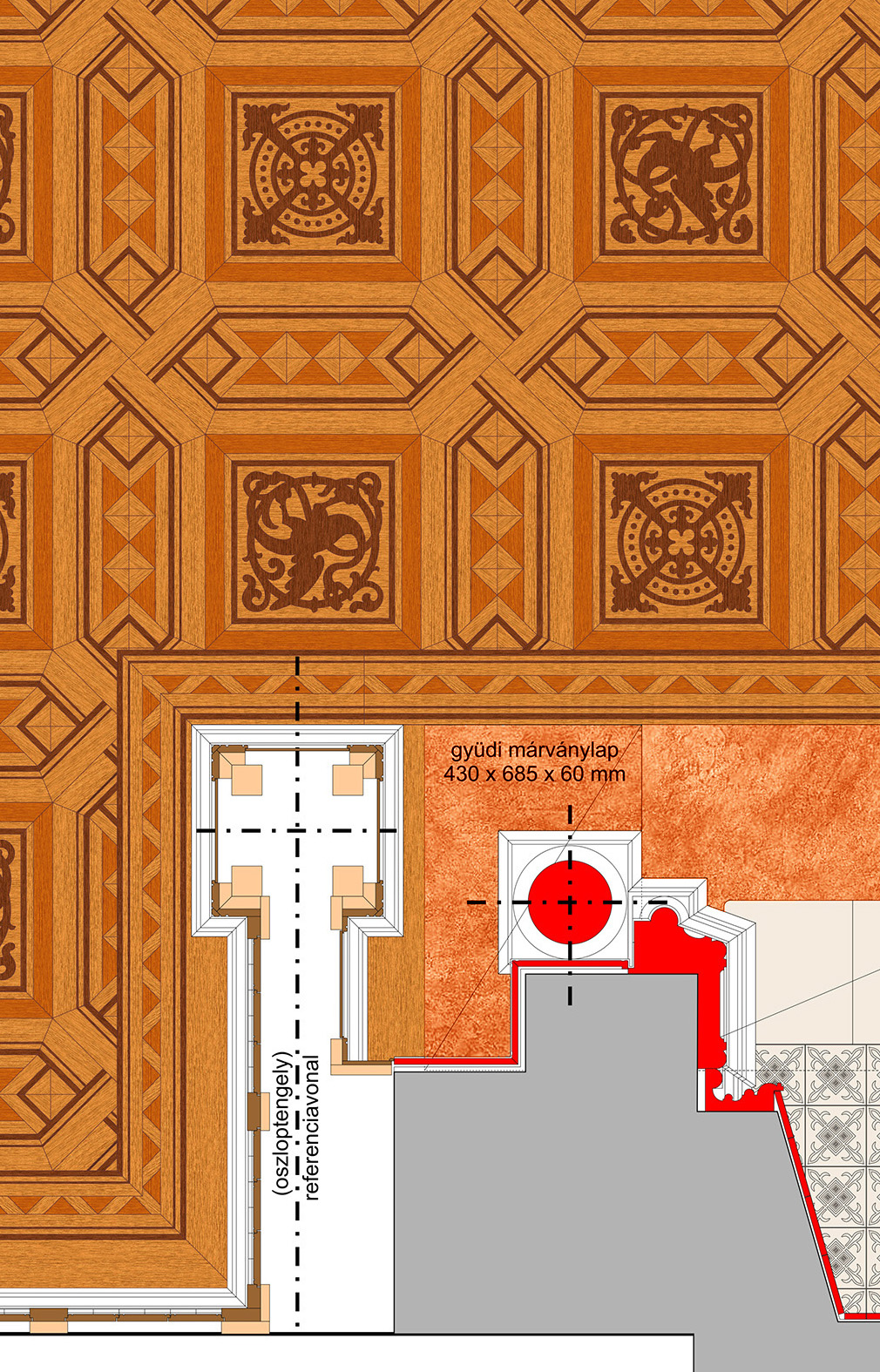

– I thought the parquet in all the rooms in the palace was different. But this was not the case. In the F building, on the main floor, practically all parquets are completely identical, only the St. Stephen's Hall and the Matthias Corvinus Hall differ from the others. The parquet in these two rooms is very similar to each other, but special compared to the others. It was surprising to me how rationally the designers in the royal palace thought. The costs also had to be accounted for by those who led the construction. Many original invoices remain. There is also the one on which Endre Thék billed a 2.4 square metre carpentry structure, which, however, also had a mirror. Hauszmann and his colleagues marked the issue: it was crossed out in red, and it was written that it was a minus 1.2 square metre mirror. With this money, Hauszmann, as he wrote in his work on the palace, was able to buy another statue, another work of art to make everything even more beautiful.

The inlaid panel parquet is made of oak, walnut, and mahogany, with five decorative motifs on the boards (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

The inlaid panel parquet is made of oak, walnut, and mahogany, with five decorative motifs on the boards (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– Now, at the end of the work, how do you see, what experience you have become richer with?

– We have gained a lot of knowledge that we can use in the future. For example, how to pattern something, who can carve or pattern in a given style without saying a word, or what technical solution can be used to solve something. One of the biggest lessons is that whoever works on such tasks must have a monumental sensitivity, not only the architects, but also the electrical and mechanical designers, and structural engineers. The re-creation of the St. Stephen's Hall and the southern connecting wing was a huge experience for everyone involved, including the contractors.

Detail of the parquet design, the work of Tibor Angyal

Detail of the parquet design, the work of Tibor Angyal

– In addition to knowledge, talent, effort, what did it take for someone to do it well?

– I think it needed a heart. For me, the point of it all was that we had a wonderful royal palace, which was not a classic royal residence because kings only stayed here for a short time, but those who designed it, gave it their all. Not only the St. Stephen's Hall, but all of it was also made from the heart. I have seen this on the plans for years because I studied them for several hours a day that they wanted to do the most beautiful out of everything and they drew everything in the most diverse way, they were geniuses, the most brilliant drawers, designers, and architects of their time worked alongside Hauszmann with amazing geometric knowledge and drawing skills.

On the wall of the connecting corridor, the excavated Hauszmann-era stucco surfaces were left free with traces of the fire that also destroyed the adjoining St. Stephen's Hall (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

On the wall of the connecting corridor, the excavated Hauszmann-era stucco surfaces were left free with traces of the fire that also destroyed the adjoining St. Stephen's Hall (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

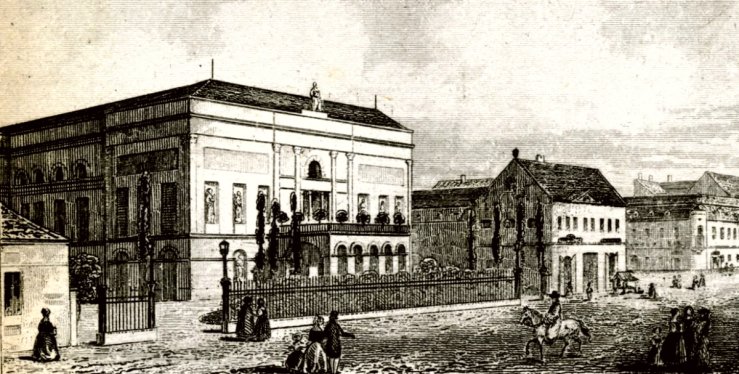

– And what the ingenious designers created with a decade and a half of work soon lost...

– The last castle captain, László Szabó, has a diary from the time of the siege. It turns out that already the Germans had tied horses into the chapel and the ornate halls Describes what day it was a shot, how they stowed away the furniture safely, how they tried to take down the tapestries of the main staircase while the bullets whistled but could not do it because they did not have a ladder. He describes how they tried to extinguish the roofs when there was no water, and how the Germans rather blew down the roof because the fire could not be stopped. And the most tragic of all is that after the palace was completed, it could stand for only forty years. It was shot, burned for weeks, and it was shocking that it was destroyed in the last two or three weeks of the Six-Year War. At the end of January, there was the great fire that could have consumed St. Stephen's Hall, burned it out, and then, even after the end of the fighting, the building was deliberately set on fire several more times. But even so, a lot of things remained from the palace.

– Do not you agree with the post-war justification that it had to be dismantled because damaged parts could not be saved?

– That was a huge lie. We could list how many buildings were demolished not because they were damaged or in poor condition, but driven by some kind of vengeance, as in the case of Haas Palace or the National Theatre. A lot of things remained in the royal palace as well. The most tragic images are not of the golden age, but post-war photos. The throne room remained almost entirely, there was also the Buffet Hall, only the suspended ceiling of the vault was torn off. The castle church is barely damaged. There was an ornate staircase in Building F, which I thought was the most beautiful space in the palace. There was the Holy Crown at the top of the dome. There was much, but it was destroyed.

Bust of the state founder St. Stephen on the Zsolnay fireplace, by Alajos Strobl (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

Bust of the state founder St. Stephen on the Zsolnay fireplace, by Alajos Strobl (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– Do you have a personal explanation for this senseless destruction?

– They wanted to destroy the palace, they smashed everything with insane rage and methodicality, not a single square metre of original space was left in it, they cleaned, remodelled what was completely unreasonable because it cost more money than it would have been cost if they have been left it as it was. The widening of Building A, the remodelling of the new dome, the west facade of the ballroom and the south connecting wing are all things like that. And when someone went up to the Castle two years ago, they saw that there was a surreal, rigid, technically very dilapidated building here. What is this really? Is this the royal palace? There is nothing royal about it. There are “social-realistic” spaces in it, with walled windows in many places due to light protection, from where you cannot see the wonderful panorama of the Danube. And it was not allowed to talk for decades that the palace was deliberately destroyed by the greatest names: archaeologists, art historians, architects.

– You were not allowed to talk about it, but a lot of people knew it. For example, you as a child, as you said at the beginning of our conversation. What makes this story so shocking even so many years after the destruction of the palace?

– You may remember how shocking it was when Imre Pozsgay announced in January 1989 that there was a popular uprising in 1956. And then when they dug up the murdered people, they were found buried face down in the 301 parcel with their hands tied with barbed wire. This picture came to my mind when during the current reconstruction, under the St. Stephen's Hall, on the ground floor, the 3-metre columns, stone cornices, and stuccoes came out, I picked up the masonry myself with my colleague Tamás Szegő. In my eyes, their hands were tied with barbed wire behind their back, and they were buried faced down there.

Not a single square metre of original space remained in the Buda Castle. Pictured is Béla IV, known as the second state founder and founder of Buda, in the Szent István Hall (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

Not a single square metre of original space remained in the Buda Castle. Pictured is Béla IV, known as the second state founder and founder of Buda, in the Szent István Hall (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

– Now, however, the St. Stephen's Hall and the south connecting wing have been rebuilt. Can we say that by recreating them, enough knowledge and experience has been gathered for the continuation to come?

–

Absolutely. It is no longer a secret that work will continue with the north wing. Restoration of the palace is a historic opportunity. Many do not know how fantastic it was and we could be just as proud of it as we were of Parliament. It has cost a lot to build, indeed, as does Parliament, but since almost nothing is left of it, this is the only way to restore the palace as authentically as possible from the walls and remains that are still standing based on the many plans, photos, and experience. It is as if we have discovered a Beethoven score, we thought was almost lost, we even have a crackling sound recording about it, and now we must perform it live again in the most authentic way, trying to grow up to the task ourselves on the go. It will not be as valuable as if it had remained in the original material of the palace, but we will do our best to make it the same. And then, I will be wondering what people will say about it.

Cover photo: Architect Tibor Angyal in the St. Stephen's Hall, 18 August 2021 (Photo: Júlia Kozics/pestbuda.hu)

Budapest, Royal Palace, Géza Györgyi, Júlia Kozics, Arts, Architecture, Csilla Halász, Tibor Angyal, Alajos Hauszmann, St. Stephen's Hall, Castle District, 1st District, Buda Castle, Pestbuda, St. Stephen

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration