Kálmán Mikszáth is undoubtedly one of the most popular figures in Hungarian prose literature. His career had a difficult start, and when he was already a nationally known novelist, a family tragedy – the death of his young son – plunged him into deep gloom. His wife, Ilona Mauks, thought that moving to a new apartment could help the situation. She was right, in the house at 13A Lónyay Street, Mikszáth soon took up pen and ink again. It is worth taking a closer look at this house that cheered him up.

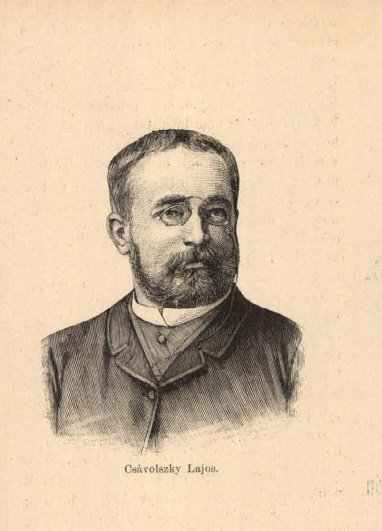

The apartment building was built in 1890-1891 based on the plans of the master builder Elek Fekete and ordered by Lajos Csávolszky (1838-1919), a journalist, newspaper editor and member of parliament.

Portrait of the owner of the house from the 16 December 1888 issue of Vasárnapi Ujság

It is not even one house, but two, with separate entrances and addresses. Our protagonist, 13A Lónyay Street, was built on the corner of Erkel Street, and next to it is the residential house under 13B. Csávolszky may have preferred the corner house because its interior and exterior design was preceded by more detailed design work. Neo-Renaissance is subtly mixed with features of several other historical styles.

.jpg)

The house from Lónyay Street (Photo: Tímea Simon)

The most spectacular parts of the facade facing Lónyay Street are the balconies above the entrance gate on the first and second floors. The semicircular console of the first-floor balcony, reminiscent of a bell, is decorated with carved plant tendrils and leaves, and in the lower centre, the leaves join around a coat of arms. The baroque atmosphere is further enhanced by the balcony's wrought iron railing and the two life-size human figures that hold the balcony on the second floor. A young man can be seen on the left and an older man with a big beard on the right, which immediately reminds the viewer of Greco-Roman mythology.

.jpg)

The two decorative balconies (Photo: Tímea Simon)

The balcony on the second floor is less patterned, but the railing of the rectangular floor plan balcony is also eye-catching. The architectural creativity can also be seen in the decoration of the windows. Of course, each level is decorated in a different way. On the first floor, under the windowsill, there is a delicately geometric shape, with rounded edges, and a canopy-like roof at the upper part of the windows, which is supported and framed by a bracket with a putto head on both sides.

On the second floor, the role of the cherubs is taken over by plant ornamentation, but on the next level above the windows, female and male faces alternately look down on the people walking on the street. The ground floor of the Erkel Street front was designed in such a way that the owner could rent it out for a restaurant or some kind of trade, and although the windows on the three floors are the same as on the other side, much less decorative elements were used here.

Entering the courtyard of the house through the arched hall decorated with Corinthian column heads, putti, and plant ornaments, we reach a cosy garden overgrown with plants (real plants). The railing of the staircase is also meticulously crafted, benches in the circular corridors help conversations between neighbours. The storms of history spared the house, so it is easy to imagine that a roughly similar atmosphere greeted those who moved in around 1891.

Part of the house (Photo: Tímea Simon)

Part of the house (Photo: Tímea Simon)

Now, take a look at Kálmán Mikszáth and the sad family event. One could already read many times about their life together with Ilona Mauks and their two marriages (the author especially recommends Zsolt Dubniczky's two articles about Mikszáth's homes in the capital on the pages of PestBuda). Ilona Mauks' memoirs published in 1922 show that after the death of their son János at the age of four (1890) during their second marriage, the already popular writer was unable to process the loss for a long time. He was not in the mood for anything, least of all writing, and his two other sons, Kálmán and Albert, could not console him either.

It was then that Mrs Mikszáth decided that they needed a new home to help her beloved husband recover from his depression. At the end of 1891, the family moved to the house in Lónyay Street, into apartment number 12 on the first floor. The owner of the house, the already mentioned Lajos Csávolszky, who often met Mikszáth as a member of parliament and as a journalist, may have had a role in choosing the place, and they had a particularly good relationship. It is possible that he recommended the newly completed apartment building to the writer's attention.

Ilona Mauks wrote about this period:

"On the first of November, we moved to a new apartment, in Lónyay Street; the layout of the rooms was different than in Dohány Street, so it was necessary to arrange them differently, and some new furniture had to be purchased. Maybe it had a good effect on my husband, I noticed that his mood was slowly rising. Well, my God, what happens one day: Berci, as usual, put together a cart from chairs in the dining room, and tied the two rocking horses to the front of the assembled cart, then he sat down very proudly on one of the chairs he imagined to be the seat of the cart, and snapped his whip: "Oops Fukszi, oops Lisel," he shouted, and also uttered a couple of German donnerwetters as a coachman would. Kálmán just listened, listened, and once, at the fact that his son was driving the horses in German, he burst out laughing as heartily as in the happy times, long, long ago. At the same time, it seemed to me, the room was filled with warmth and sunlight, the little faces curled up, the older boy slid forward to the little one and kissed him back and forth in the overflowing joy of his heart. "Daddy laughed..." he whispered happily.

Part of the house (Photo: Tímea Simon)

The Mikszáth Family lived behind the windows on the first floor on the left (Photo: Tímea Simon)

Not long after, he again felt the urge to not only fulfil his journalistic obligations but to turn to prose again. He wrote the novels Ghost in Lubló [Kísértet Lublón], St. Peter's Umbrella [Szent Péter Esernyője] and The Siege of Beszterce [Beszterce ostroma] at that time and in this house.

The press of the time loved Mikszáth and often published tributes to him. In 1892 and 1893, several articles mentioned that Mikszáth liked to be escorted home after a tiring session in the House of Representatives or at the end of an editorial meeting. In such cases, he also invited his friend in, and as long as there was a topic (there was always a topic), he would have a pleasant conversation with his companion until dawn.

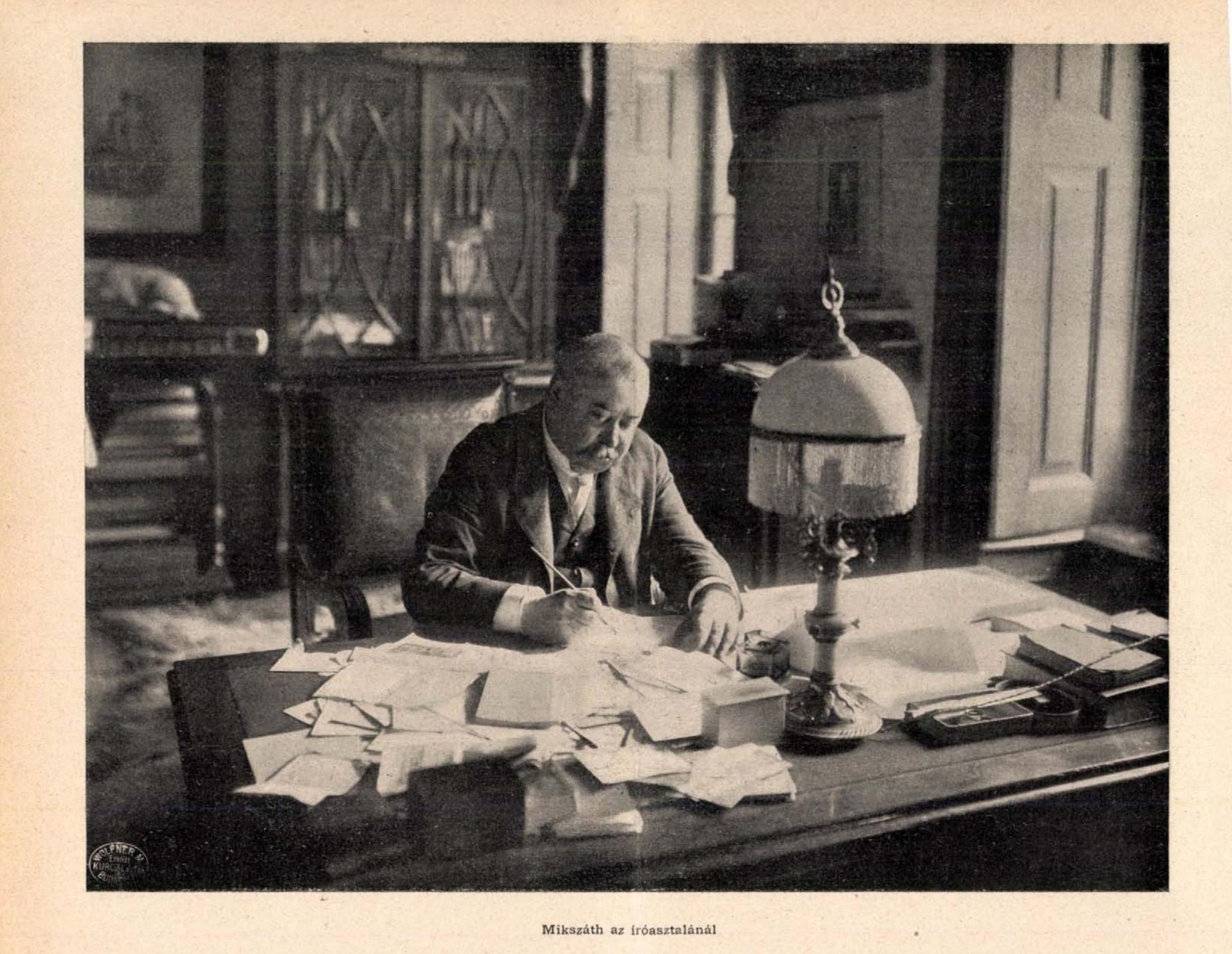

Mikszáth at the desk of his last apartment, in the 6 March 1910 issue of Uj Idők

The family moved in 1896. They tried two more apartments, and finally, in 1902 they found a comfortable home on the corner of Reviczky Street and the square that bears his name today. The apartment with a large floor area and a separate study room satisfied all of Mikszáth's needs, but it is very likely that when he sometimes thought of the house at 13A Lónyay Street, he only had good feelings about his former home in Ferencváros and the house where he regained his cheerfulness.

Cover photo: The house where Mikszáth lived, facade from Lónyay Street (Photo: Tímea Simon)

PREVIOUS ARTICLES (in Hungarian):

Pest-Buda stations of a life's journey: Kálmán Mikszáth in the capital

One of the city's most atmospheric squares has been named after Kálmán Mikszáth for 110 years

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration