The Treaty of Trianon, signed on 4 June 1920 and forced on Hungary, also hindered the development of domestic air transport, as one of its provisions prohibited motorised flight in the country.

Thus, despite the fact that the first Hungarian airline was established in February 1920 - which primarily operated mail services and from the very beginning performed its tasks with forty-two traffic and school planes - its operation and, with it, domestic civil aviation became impossible for a long time.

As the law incorporating the Treaty of Trianon into the Hungarian legal system puts it:

"For six months after the entry into force of this Agreement, the production, import and export of aircraft, aircraft parts, aircraft engines and aircraft engine parts is prohibited throughout Hungary."

In addition to the ban, the remaining existing aircraft and engines also had to be destroyed, a total of 70 airframes and 110 engines fell victim to the destruction, according to contemporary reports. Since the ban was for 6 months, and the legislation - Act 33 of 1921- was promulgated on 31 July 1921, the restriction would have been in effect only until 6 January 1922.

The Mátyásföld airport in 1928 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 94209)

However, the air traffic control committee extended the flight ban in 1922, first until May, and then the case dragged on. The German ban was already lifted in May 1922, but the Hungarian restriction remained in force after that, and in June, the victorious powers made the lifting of the flight ban conditional on the acceptance of very strict criteria. The Pesti Napló wrote on 14 July 1922:

"Only recently, four weeks after the liberation of German aviation, the entente's list regarding the lifting of the ban in Hungary arrived from Paris, which informs the Hungarian government that the entente wishes to maintain the same restrictions on Hungarian aircraft that were tailored to German aviation. According to this, the maximum speed of the machines per hour should be 170 km, their height 1006 m, and their useful weight only 600 kg, and the engine of single-seat machines cannot be larger than 60 horsepower."

However, the agreement lifting the restriction was only signed with the Hungarian government in October 1922, which was already eagerly awaited at home, because, as the newspaper, Magyarország wrote on 27 October 1922:

"However, Hungary did not leave these three years completely unused either. Three Hungarian air traffic companies were founded and are waiting for the ban to be lifted so that they can take action. One wants to cultivate the Vienna-Budapest line, the other will establish itself on the Budapest-Zagreb-Fiume-Rome route, and the third will obtain a license for the Budapest-Belgrade-Bucharest line. All three companies obtained the necessary capital, but they also received a promise from the government that it would help and support them."

In other words, in Hungary, domestic companies were ready to jump to launch international flights from Budapest. At that time, the civil airport was still in Mátyásföld, which was already in use, since the Paris-Bucharest flight operated by French-Romanian interests landed here, and the Franco-Romanian Air Traffic Company also operated other flights, only Hungarian companies could not fly.

Bánhidi-Lampich BL-6 type aeroplane, the first two-seater school plane in Hungary in 1929 in Mátyásföld (Photo: Fortepan, Hungarian Museum of Science, Technology and Transport / Archive / Negatives / collection of widow Ábrahámné Batta, Reference No.: 1124)

Even after the lifting of the ban, certain measures limiting flights remained, for example, the power of aircraft engines could not exceed 200 horsepower. It was not until 1927 that Hungary regained full freedom of flying.

After the ban was lifted on 17 November 1922, the Hungarian Aviation Company, Aero Express and the International Air Traffic Company started Budapest-Vienna flights, while only the International Air Traffic Company flew to Belgrade.

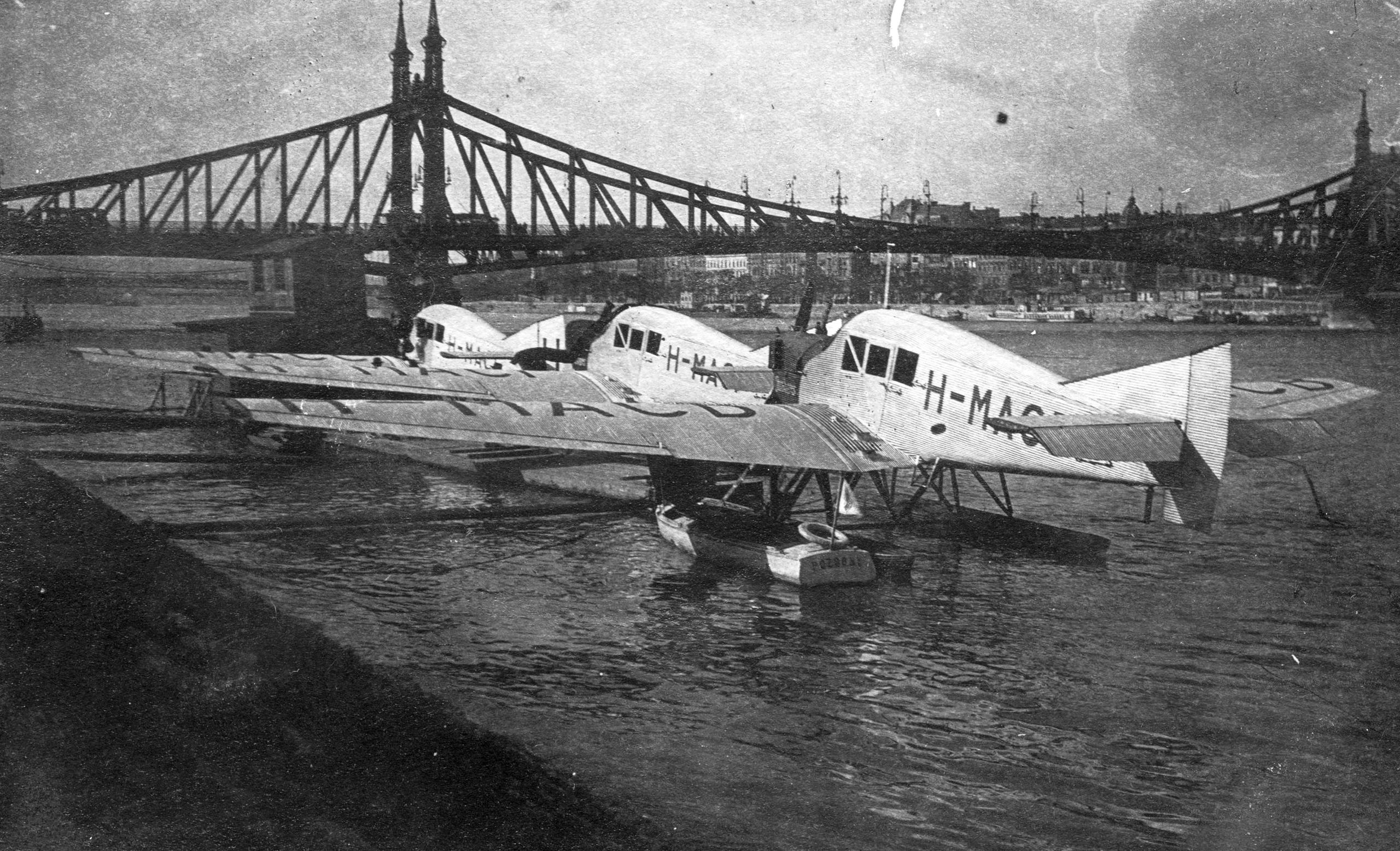

Junkers F13 passenger planes at Gellért Square on the Danube (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 24829)

The traffic at that time was negligible from today's perspective, but at that time they saw it as the first step of development. In 1923, the three mentioned companies made a total of 1,250 trips, flying a total of 1,589 passengers, and a year later they could boast of 2,837 passengers with 1,658 flights.

Of course, the planes of that time were not similar to today's airbuses, for example, Aero Express flew with Junkers F 13, whose water versions departed from Gellért Square in front of the Ferenc József Bridge and could only carry 4 passengers.

Hungarian aviation thus resumed, Budapest joined international air traffic, and aircraft with the Hungarian flag also flew. This was important not only to get those few thousand people to their destination faster, but also to keep Hungarian aviation alive, not only the civil one but also the military one, which was completely forbidden at the time and could only be developed in secret.

Cover photo: A larger passenger plane at the Mátyásföld airport, in 1928 (Photo: Fortepan, Hungarian Museum of Science, Technology and Transport / Archive / Negatives / Collection of the Hungarian National Museum Historical Gallery Reference No.: 1167)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration