Truly great works can be recognised by the fact that they do not become obsolete: what they say is just as valid decades and centuries later as it was when they were born. This is also the case with the National Anthem. When Ferenc Kölcsey finalised the words of the poem on 22 January 1823, Hungarians were living in the period of "national awakening", the beginning of the reform era. That is when the country became a nation, and "taking stock" was part of that: what is valuable to us, what binds us together? What makes us a nation? History - which is known since Cicero that the teacher of life - helps to answer these questions.

Lesser known portraits of Ferenc Kölcsey include József Kliegl's painting of the poet in 1834 (Source: HNM)

The National Anthem (Hymnus in the original spelling) beautifully frames the history of Hungarians from the conquest ("You brought our ancestors up / Over the Carpathians' holy peaks") to the sufferings of the recent past, as if anticipating the tragedies of the fights for Hungarian liberty in the 19th and 20th century: (And Ah! Freedom does not bloom / From the blood of the dead, / Torturous slavery's tears fall / From the burning eyes of the orphans!").

.jpg)

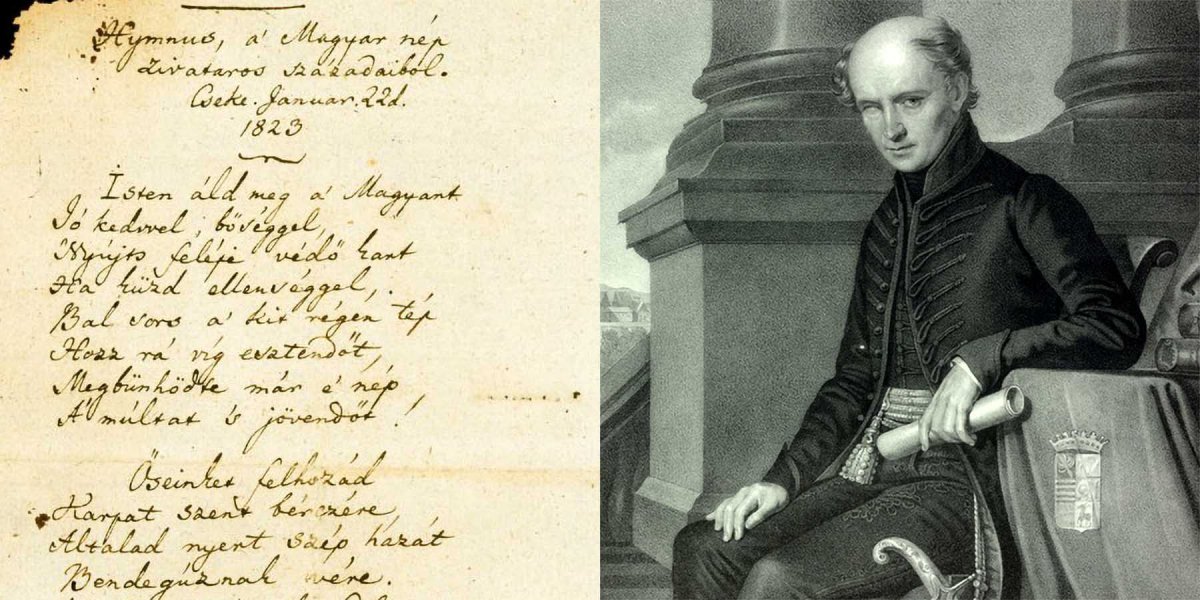

The original manuscript of the National Anthem (Source: oszk.hu)

At the time of Ferenc Kölcsey's death in 1838, the work was not yet considered a national anthem, and although it was completed in 1823, it appeared in print only in 1829 in Károly Kisfaludy's almanack entitled Aurora, and then in 1832, in the first volume containing Kölcsey's works. It was set to music in 1844 when Ferenc Erkel won the tender, and the work was presented at the National Theatre in Pest that same year. Although the National Anthem has been sung since the 1840s (in the beginning, alternately and together with the Appeal [Szózat]), it was officially added to the national symbols only in the 1989 constitution.

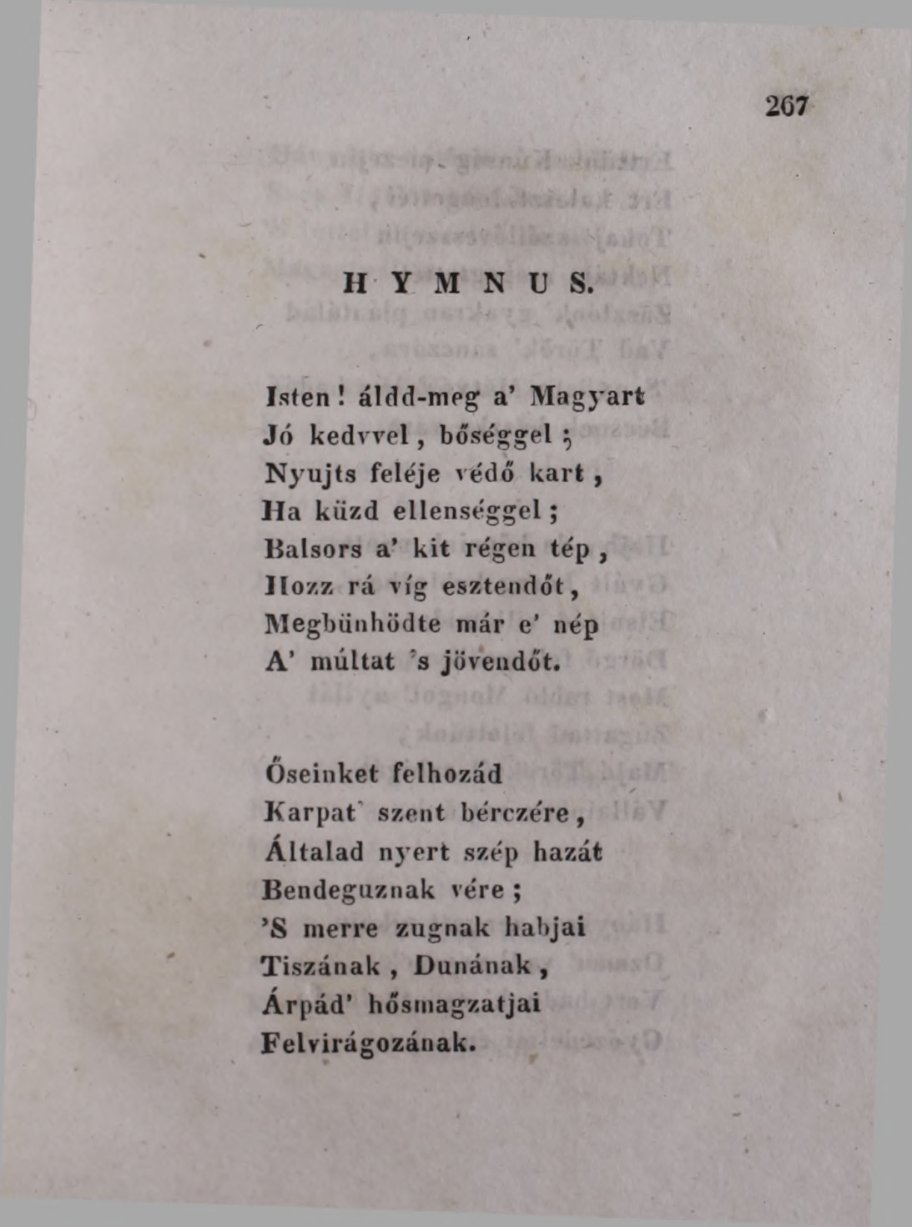

The National Anthem first appeared in print in Károly Kisfaludy's Aurora almanack in 1829

Kölcsey gave the following subtitle for his work: "From the Stormy Centuries of the Hungarian Nation", listing the many sufferings that the Hungarian people had to go through, and asking God to bless and have mercy on the Hungarians since they have already suffered for the sins of the past and the future. What is dramatic about the National Anthem is that Hungarians could formulate this request now as well, in 2023, just as their predecessors did. The Magyarság newspaper, for example, in its Tuesday issue of 23 January 1923, in an article titled "Százéves a Himnusz" [The National Anthem is a hundred years old] states:

"[Kölcsey] felt the recurring memory of centuries, the bitter centenaries, with writing under the title: from the stormy centuries of the Hungarian people. The centuries-old storms of the Hungarian people have been renewed in our present-day destiny, and the stanzas of the hundred-year-old National Anthem, with their heavy rolling, have found their time again in today's time."

It is not difficult to guess what the author was referring to: the country torn apart at Trianon, still bearing the traces of the revolutions and the Hungarian Soviet Republic, has just begun to reorganise itself. As the article quoted above says about World War I, "the nervous shock of the recent war shakes our hands", then, referring to the lines of the National Anthem, it continues:

"We feel that we need to renew again the offering of our covenant with our God. We have to put it into one of the pans and honestly measure again what we have been entrusted with by providence. Kunság's ears of corn, Tokaj's vines, the victories we won over our enemies; and into the other pan we must once again weigh our sins, the centuries of ingratitude, the disrespect of our fate, the failure of our destiny, the flags planted on foreign walls and the flags we failed, the foreign flag rags, the cowardice, sick hatred, and all those sins for which God will again send his thunderbolts in his thundering nature.”

The events of Hungarian history included in the National Anthem come to life on the relief created by Róbert Smidt, inaugurated on 20 January in the Offices of the National Assembly (Photo: Zsolt Szigetváry, MTI)

The 100th anniversary of the National Anthem was commemorated in January 1923 by many other newspapers, but the official state celebration was held on Saturday, 9 June, in Mátészalka. January was more about the centenary of Sándor Petőfi's birth, but the June celebration was reported in detail by the contemporary press.

The 10 June 1923 issue of Budapesti Hírlap also published a thorough report on the event in June. The article reveals that the governor of Hungary, Miklós Horthy, took part in the event organised in Mátészalka, the "seat of the truncated county of Szatmár", and the National Assembly, the government, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, literary and social associations were also represented. The honorary assembly of the county was held in the gymnasium of the state civil school, which served as the framework for the celebration. As they wrote, "the hall decorated with flowers and flags was filled to capacity by the county's dignitaries and ladies dressed in Hungarian finery".

The festive meeting was opened by főispán [Lord Lieutenant] László Péchy, "commemorating Kölcsey, who was, above all, a true patriot, whose poems testify to his true love of country and race. In our great national misfortune, let us be inspired by Kölcsey's warm patriotism and let us engrave his teachings in our hearts with an ore stick".

Minister of Culture Count Kunó Klebelsberg also gave a long speech, praising Kölcsey's political career and saying:

"For every holiday, Kölcsey gets more and more into historical perspective, and thus we see even more clearly the eternal in his person and work. A part of his poetry, his works of fiction, criticism and aesthetics are now only of literary historical importance. But it is beyond all doubt that he left us an eternal song and an eternal act. His eternal song: the National Anthem, which - as long as Hungarians live - will be sung by his nation in moments of spiritual upliftment".

The minister called the National Anthem "the great opening of the reform era", adding that it is much more than that, as religious and national sentiments merge in perfect harmony, "and the poem is woven into the great events of the millennial national past in such a way that perhaps there is no national anthem in world literature that reflects the specific spirit of the people in question as the reverent, dignified and truly Hungarian lines of Kölcsey's National Anthem." According to Klebelsberg, the strength of the National Anthem lies in the fact that, unlike the anthems of other countries (he mentions the French Marseillaise and the German Wacht am Rhein), it encompasses the whole of national life and the national past, not just one episode.

The coverage reveals that after the ceremony, the governor received the members of the Kölcsey Family for a separate hearing: Sándor Kölcsey, Gábor Kölcsey, Ákos Kölcsey, István Kölcsey, Géza Kölcsey and Béla Kölcsey Jr., on whose behalf Sándor Kölcsey welcomed the governor.

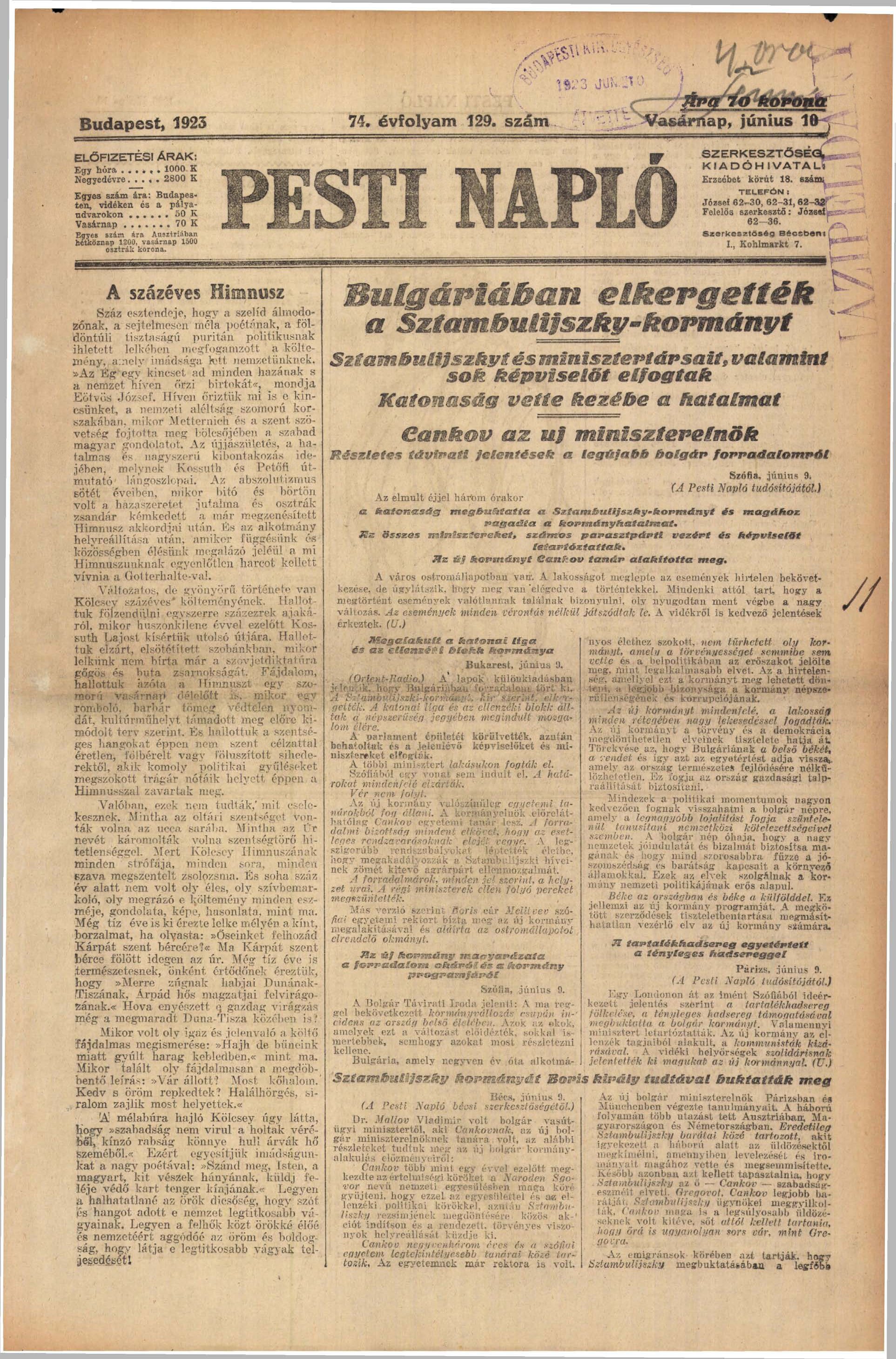

The front page of the 10 June 1923 issue of the Pesti Napló with the editorial about the National Anthem (Source: arcanum.hu)

The coverage of the newspapers of the time (with the exception of the literary papers) mostly focused only on the description of the Mátészalka celebration and politicians' speeches, but at the same time, Pesti Napló wrote about the National Anthem in an editorial on the front page of the issue of 10 June 1923. In the article entitled The Century-Old National Anthem, the history of Kölcsey's work is recalled much more thoroughly than in the majority of newspapers:

"Kölcsey's hundred-year-old poem has a varied but beautiful history. We heard it rise from the lips of hundreds of thousands at the same time when we accompanied Lajos Kossuth on his last journey twenty-nine years ago. We heard it in our closed, darkened room when our souls could no longer bear the arrogant and stupid tyranny of the Soviet dictatorship. Pain, we have since heard the National Anthem on a sad Sunday morning, when a destructive, barbaric mob attacked an unprotected printing house and cultural workshop according to a premeditated plan. And we heard the holy sounds from immature, hired or instigated youngsters with not-so-holy intentions, who disturbed serious political gatherings with the National Anthem instead of their usual obscene notes."

Gyula Krúdy commemorates the anniversary in his typically anecdotal article entitled 'A Hymnusz bölcsőjénél" [At the Cradle of the National Anthem], in the Nyugat's 4th issue of that year published on 16 February 1923. Krúdy says this about the National Anthem:

"It has become the prayer of Hungarians because the pride of the nation brought from the east is sprouting in its ranks just as the Christian humility undertaken between the Danube and Tisza is bowing down. The poet Kölcsey could have written poems with more literary value, but the foremost of Hungarian rhetoricians could not emit a more powerful national voice from his soul." "Everyone in the country was already awake and Kölcsey's National Anthem found open ears."

After the National Anthem was written, the Hungarians had two more stormy centuries, so it is not difficult to find national tragedies among the events of the past 200 years even during the anniversaries. And Hungary's National Anthem is just as relevant today as it was a hundred or two hundred years ago, even now Hungarians feel that they have already suffered for not only the sins of the past but also of the future. Hungarians can therefore ask God today: Bless the nation of Hungary with your grace and bounty and bring upon it a time of relief.

Cover photo: The original manuscript of the National Anthem and a portrait of Ferenc Kölcsey

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration