The name Lechner may sound familiar to those interested in architecture since Ödön Lechner was one of the most talented, style-creating geniuses in the country. Under his influence, his two nephews, Jenő and Loránd, also studied as architects, of whom Jenő was the more ambitious, and like his uncle, he also worked hard to create a national architectural style. At the Royal Joseph University of Technology, Alajos Hauszmann was his teacher, from whom he brought with him a love of the Renaissance, so even at the time of his graduation in 1902, he had both a respect for historical styles and a desire to create something new.

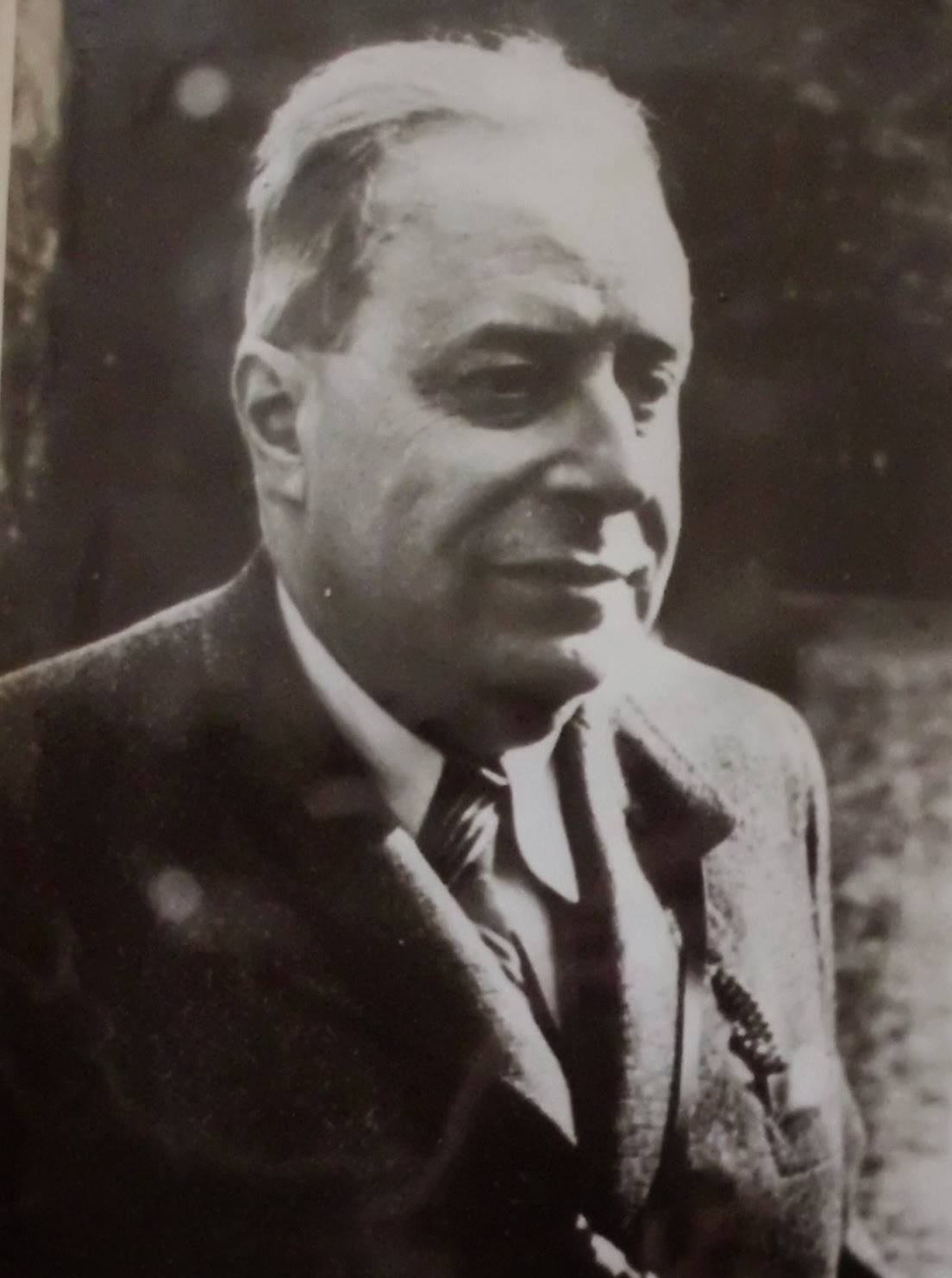

Jenő Lechner's photograph from the 1920s (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

This was actually typical of the entire era because in addition to the Art Nouveau fever at the turn of the century, historical styles were also present, and from the mid-1900s, representatives of national romanticism also lined up, who revived the structural and formal toolkit of folk architecture. In fact, the mixing of styles was already common in the last third of the 19th century, although this only meant the mixing of different historical trends: for example, neo-Baroque with neo-Renaissance, neo-Romanesque with neo-Gothic. At the turn of the century, however, the picture became even more mixed, which is also reflected in Jenő Lechner's early work.

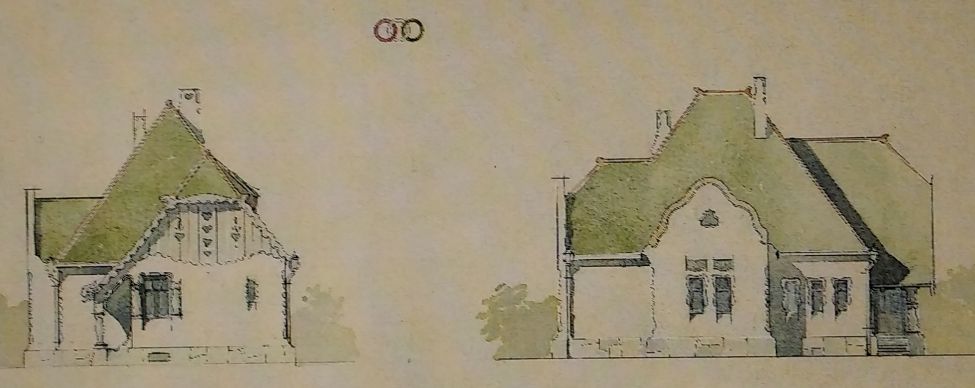

Floor plan of a small family house, 1903 (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

Even as a recent graduate, Jenő Lechner showed off his talent in the field of designing residential buildings, as in 1903 he won the competition for small family houses advertised by the magazine Művészet. These still follow the Hungarian style of his uncle almost completely, but five years later, in the case of the residential houses and villas that were built, this changed significantly. He experienced that society does not welcome the creations of Ödön Lechner and his circle, which completely broke from the usual forms. He believed that if he tried to create national architecture based on a historical style, it would be more successful.

Design plan of Ferenc Rákóczi II's grave monument, 1909 (Source: Építő Ipar, 14 November 1909)

The reburial of Ferenc Rákóczi II and his companions in 1906 directed his attention to the crenellated renaissance that spread on the prince's ancient estates in the eastern part of the Highlands in the 16-17th century. He saw the ideal basis for the creation of the Hungarian architectural style in this, but he significantly transformed the original facades and also used other historical styles in order to give his buildings truly unique facades. He especially liked the Gothic, because its peak arches harmonise beautifully with the upward-sloping crenellations.

The south facade of the villa at 1 Lovas Road (Source: Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

In the villa standing at the foot of Buda Castle, at the beginning of Lovas Road - whose original neo-Renaissance facade was remodelled in 1908 on behalf of Viktor Gyarmathy - he supplemented the windows with semi-circular shutters with pointed arched string courses, and above the windows of the corner block projecting forward in a semi-circular arch, he sunk fields with sawtooth closures. He gave the side facing Tabán a truly unique gable: the truncated bun end of the gabled roof is cut into the middle so that only the two edges remain at their original height, and they surround the roof as if there were two pointed crenellations. Their wavy profile also lends them an Art Nouveau character.

Madonna relief next to the entrance of the villa (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

According to the procedure popular at the turn of the century, the designer also divided the windows into small squares with many dividers, and he designed the terrace railing on the south side of the villa in the same way. The entrance opens on the opposite, north side, and visitors are greeted by the Madonna relief placed on the left side of the gate. Lechner, a devout Catholic, liked to use this kind technique on residential buildings, it almost became his trademark.

House at 7 Németh László Street in the 6th District (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

He designed a completely different type of building for Gézáné Tóth: not a detached villa in Buda, but a closed terraced apartment building in Pest in the 6th District. The individual styles are mixed in different proportions on the facade as well: the Gothic appears more decisively, and for passers-by, this is the most striking, because, in the narrow Németh László Street, the eye can only take in the ground floor. This part is dominated by the motifs of the pointed arches cut into the balcony console. The opening closest to the entrance is still filled with a Madonna relief. The window above the gate is also pointed, but the hood itself is decorated with Art Nouveau wavy lines. The windows on the first floor are divided by the previously seen square mesh dividers, but this time the main cornice also received a beautiful design, it's just a shame that it's hard to see: the designer placed sunflowers typical of Art Nouveau in arched fields.

The Thurzó House in Lőcse [today Levoča, Slovakia] (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

In the next few years, Lechner kept his buildings in a similarly mixed style. In the villa designed for Mihály Petrovits on Pasaréti Road, the truncated gable roof reappeared in 1910, but this time he decorated the crenellation formed on the two edges with another favourite motif, the spiral line. This also comes from the Highland Renaissance, it can be seen, for example, on the most famous monument of the style, the Thurzó House in Lőcse [today Levoča, Slovakia].

Villa at 59 Pasaréti Street (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

He also designed the structure of the southeastern corner block of the villa in accordance with the requirements of this style: a solid parapet wall rises above the narrow windows, which is closed off by a dense crenellation. The pointed-arched crenellations stand on top of the pillars dividing the parapet, and their surface is filled with plant ornaments. On the other hand, figural reliefs were placed at the foot of the pillars: charming putti solve the austerity of the rather massive villa built on a high stone plinth. The complex roof, following the structures of folk architecture, partially fulfils the same purpose.

4 Mészöly Street in the 11th District nowadays (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The design of the villas not only earned Jenő Lechner professional glory, but also strengthened him financially, so in 1910 he also designed a residential building for himself. More specifically, he worked together with László Warga, who was already his classmate at the University of Technology, and with whom he also collaborated in connection with many of his other works. The building is located at 4 Mészöly Street, opening from Bartók Béla Road, right at the foot of Gellért Hill. Its floor plan forms the letter U, the legs of which face the hill, but its main facade is not located between them, but on the side of one of the wings, as that is visible from the street. This is dominated by a huge closed balcony, the surface of which is decorated with plant ornaments using the sgraffito technique, which was also often used in the Highland Renaissance. These motifs, on the other hand, do not come from the Highlands, but from Transylvania, where Lechner also went on a collecting trip a few years earlier. The crenellations only appear in a stylised way on the building: on the top of the closed balcony, and in the pointed, leaf-like sections placed at the corners of the two wings. The mixing of styles can also be observed in the loggias of the wings, because while the openings in one have pointed arches, in the other they are semicircular.

The closed balcony of the villa on Mészöly Street (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

People can witness Lechner's religiosity here - given that it is his home - several times: on the closed balcony, two biblical quotes taken from King Solomon can be read: "Unless the Lord builds the house, those who build it labour in vain." "Unless the Lord watches over the city, the watchman stays awake in vain." The visual counterpart of this popular religious text is the circular Nativity of Jesus relief placed on the edge of the main facade, on which Mary kneels and worships the shining baby Jesus.

It is also clear from the above four buildings that Jenő Lechner mixed historical style elements with Art Nouveau in a very individual way, with which he created characteristic facades. He was a daring artist, and although he failed to achieve his original goal – a national style sympathetic to society as well – posterity already appreciates his efforts, as he owes fantastically exciting buildings to him.

Cover photo: Villa at 59 Pasaréti Road (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration