Already in the 19th century, there was a demand for gambling in Hungary, which the state also recognised and regulated by law: in 1897, instead of the previous number lottery, it created the class lottery, which operates according to different rules. They leased the right to organise it to a joint-stock company, which rapidly acquired a huge fortune and expressed its wealth already in 1899 by building a representative palace.

For this, they acquired a newly freed plot of land: on Eskü Square (today Március 15. Square), the Budapest Public Works Council demolished almost all the buildings just a few years earlier in order to regulate the area in connection with the construction of the Erzsébet Bridge. The Hungarian Royal Class Lottery Company invited Albert Kálmán Kőrössy and Artúr Sebestyén to prepare the plans, who created a Neo-Baroque facade with a hint of Art Nouveau. The richness of detail in the style perfectly expressed the enormous amount of money involved in gambling even then, and the vibrant silhouette of the building further enriched the panorama of Pest.

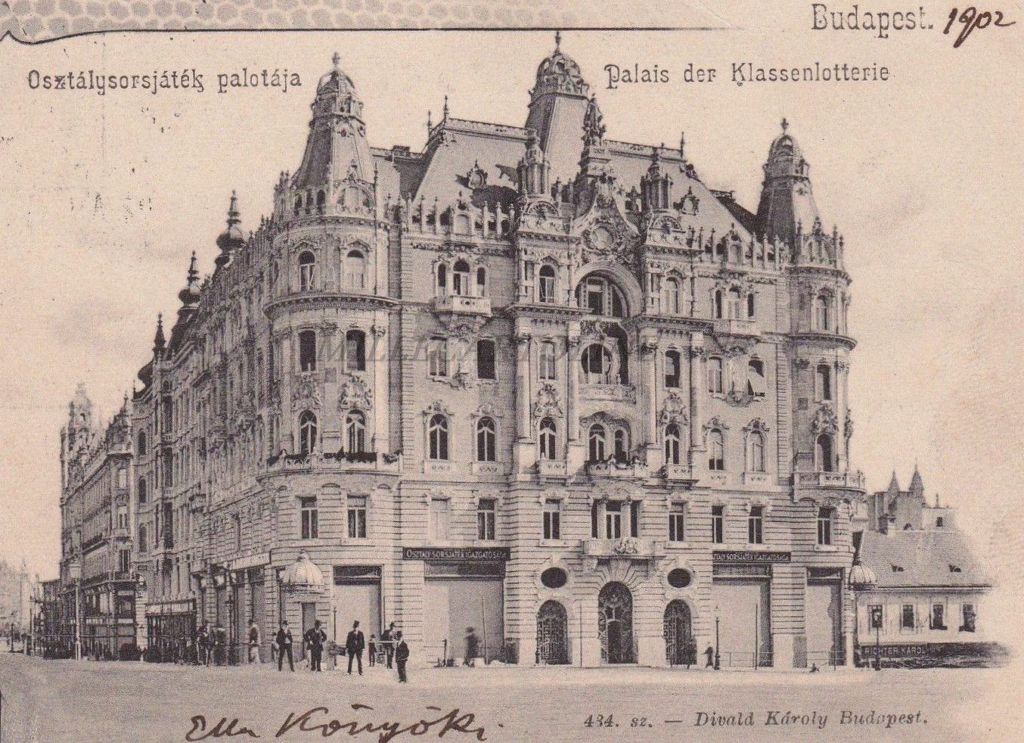

The Class Lottery Palace at the beginning of the 20th century (Source: hungaricana.hu)

The Neo-Baroque ostentatiousness was particularly represented by the high roof, which was complemented by superstructures similar to spires on both sides and in the middle. At the top of these, the designers placed decorations reminiscent of crowns, each ending in a rose. The same roses decorated the crenellation marching in front of the roof. In the middle of the main facade overlooking the Danube, a huge, semi-circular window was sunk, above which the fantastically richly decorated pediment began. The statue of Fortuna, the goddess of fortune, was placed on top of it. Art Nouveau appeared in the details: the windows' hood moulding and the gate's grill were decorated with various plant and animal forms (irises, poppy heads, peacocks).

Although the building had a rectangular floor plan, semi-circular protrusions emerged from the corners facing the Danube, and a courtyard covered with a glass roof was opened inside. Shops and the offices of the joint-stock company were located around this on the lower levels, and rental flats were lined up above. The architects also paid a lot of attention to the furnishings, because they asked Ödön Lechner to design it, who used the Hungarian design language here as well.

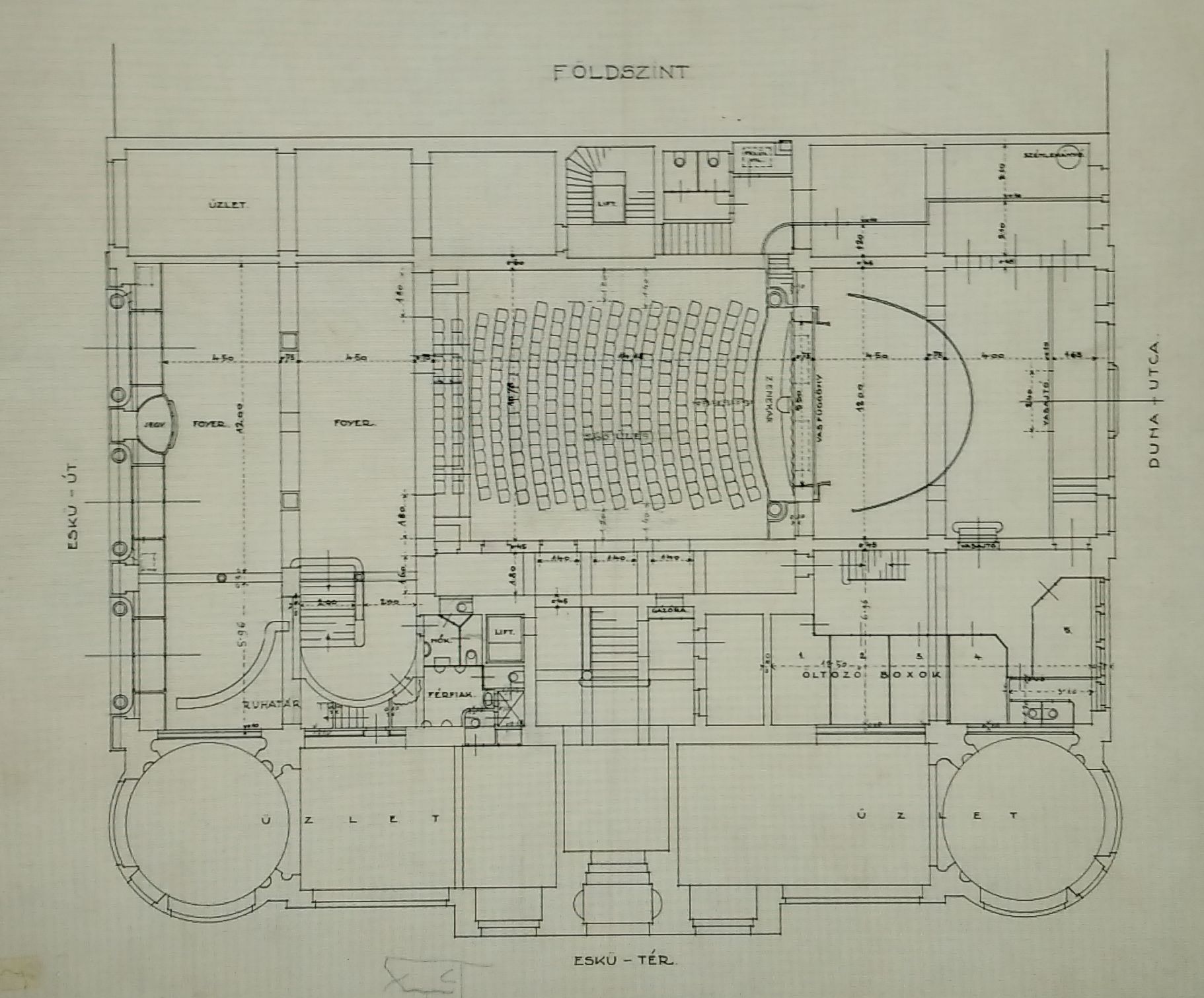

The floor plan of the Palace, including the theatre (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

Less than two decades after the handover of the palace, large-scale remodelling work had already begun: at the very beginning of 1918, Árpád Vámos and his wife, Vilma Medgyaszay, decided to found a new theatre, which they wanted to house there. During World War I, this seemed like a surprising undertaking, but the financial background was provided by one of the husband's wealthy friends. By the way, Vámos created the theatre with peace in mind, to which his wife, the celebrated actress, gave its name. Ödön Lechner's nephew Jenő Lechner was asked to prepare the plans.

Actress Vilma Medgyaszay (Source: National Heritage Institute)

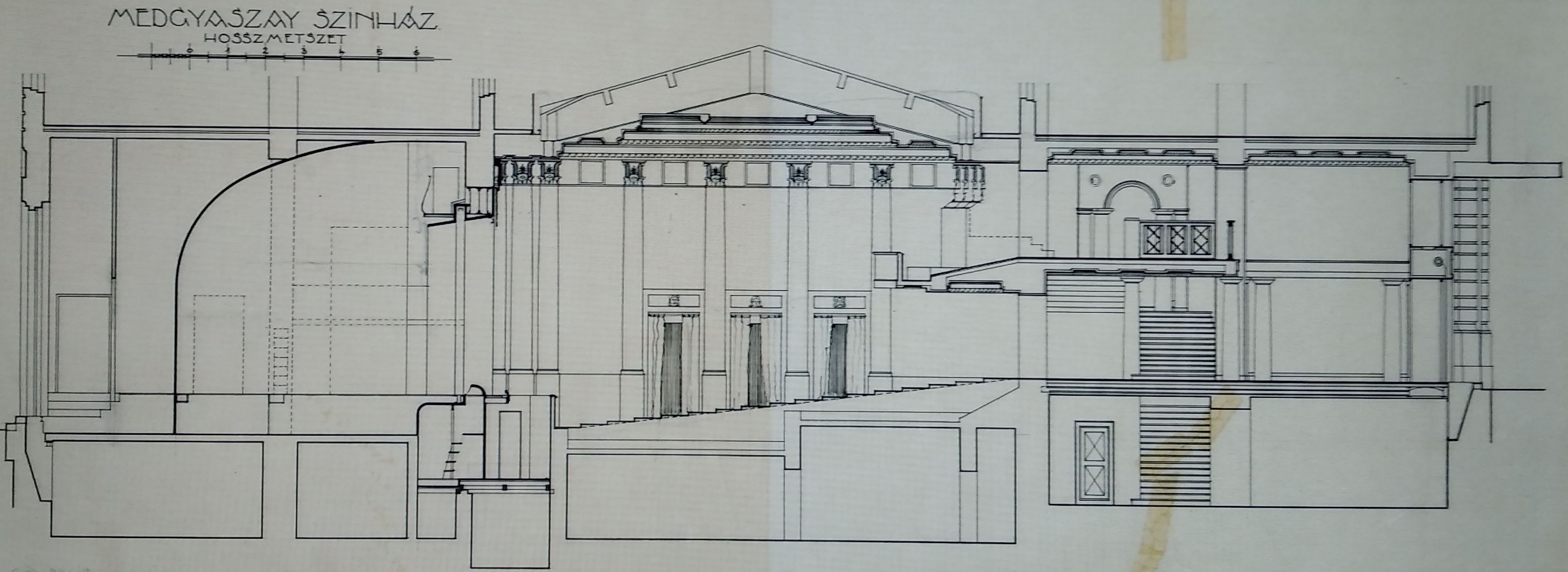

He placed the theatre in the building in such a way that it occupied the basement, the ground floor and the first floor, and he designed its entrance in the central axis of the facade on Eskü (today Szabad Sajtó) Road. From the street, people could reach the auditorium through two vestibules opening from each other, which filled the roofed inner courtyard of the building. The way to the boxes led from a gallery on the upper floor, and the stage was located at the end of the building facing Duna Street.

Jenő Lechner in the company of two actresses (Source: Színházi Élet 1918, Issue 52)

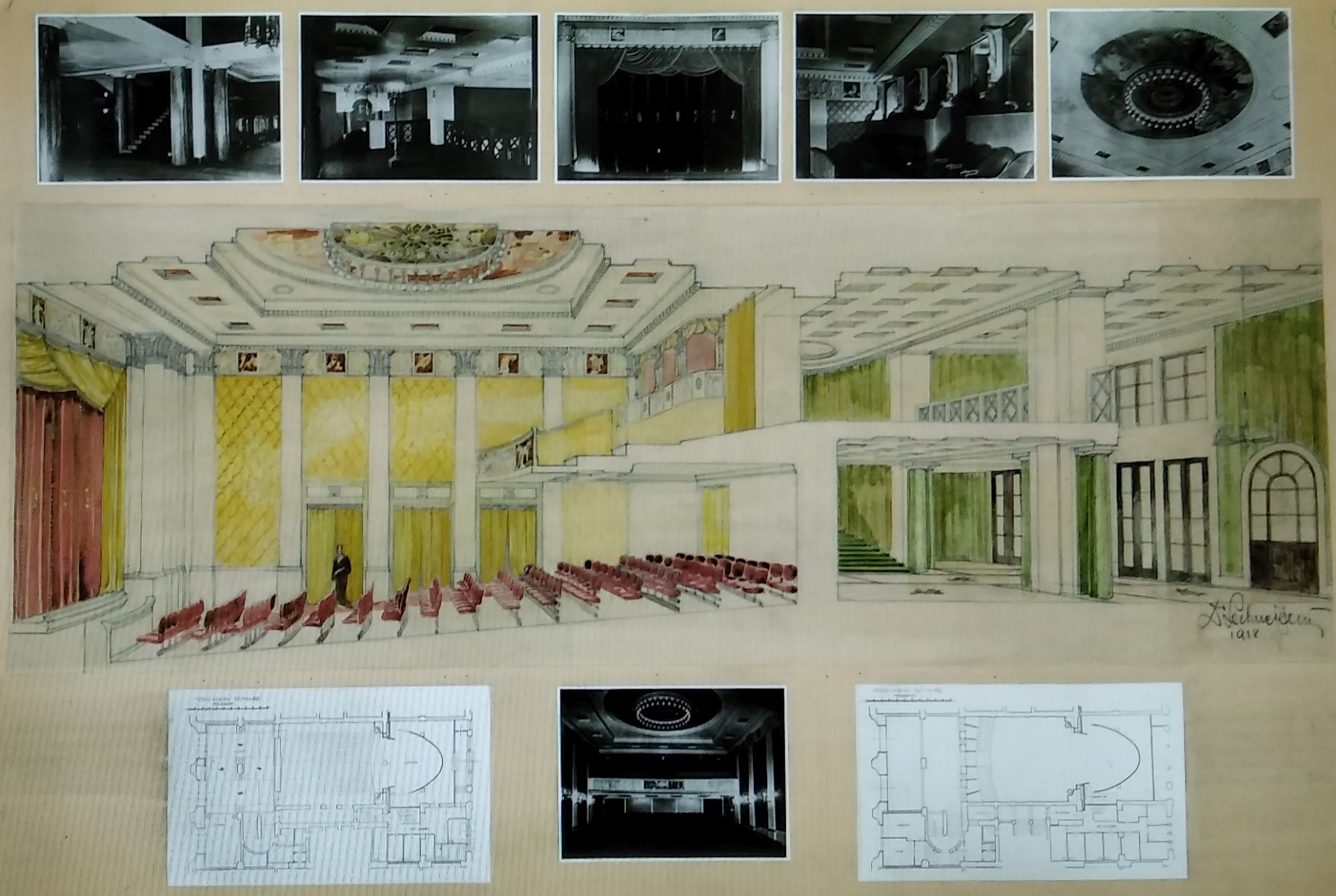

The interior design of the theatre strongly contrasted with the Neo-Baroque facade, as it was designed by Jenő Lechner in Empire style, which was a more elegant, less harsh version of classicism at the very end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. Its name comes from the French word 'empire', as it spread during Napoleon's conquests. Jenő Lechner reached out for this because he felt that the fever of Art Nouveau had subsided by the 1910s, and as a counter-effect, classicism had strengthened, which meant the rediscovery of ancient architecture. The horrors of World War I then made it dominant: people wanted security, which was matched by the well-known, thousand-year-old forms. This style was also obvious in the theatre because it referred to the Greek traditions of acting.

The location of the theatre can be seen on the section of the Palace (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

In Hungary, however, austere classicism was never able to spread, and a more ornate and elegant version of the style emerged even in its heyday at the beginning of the 19th century. Jenő Lechner, who enthusiastically researches the history of architecture, named this palatinus [palatine] style in Hungarian, referring to Palatine Joseph's career spanning the entire era (the Latin word palatinus means palatine). In the theatre, he also enforced more atmospheric classicism in the use of bright colours: he painted the side walls of the two-story lobby green, which were supported by huge wall pillars. He placed mosaics of dancing couples on the floor, which also represented different eras of history: an ancient dancing couple, a medieval knight and his bride, a Rococo couple, and a modern ballroom dancing couple were on display.

Three hundred and forty people could take seats in the auditorium and enjoy the extremely elegant furnishings before and after the performances. The side walls with yellow wallpaper were divided into five sections by pillars with palm leaf heads, and the designer installed stylish wall arms on them, which were decorated with carvings reminiscent of candles: as if a tallow was flowing down their sides. A frieze decorated with yellow and white reliefs and paintings depicting allegorical scenes ran in line with the pillar heads.

Colour plans and some black-and-white photos of the theatre (Source: Kiscelli Museum of Budapest History Museum)

At the end of the auditorium towards the entrance, there was a balcony, the parapet of which was filled with two reliefs and a painting: the former symbolized Greek comedy and tragedy, and the latter represented wandering actors travelling in oxcarts. Vilma Medgyaszay and Árpád Vámos were also recognisable among the figures. Above the balcony, six boxes were created. The designer formed the edges of the ceiling in a coffered pattern, and the chandelier hanging in the middle was surrounded by a circular painting by Sándor Unghváry.

The immediate surroundings of the stage also received an ornate design: it was bordered on both sides by wall pillars with palm-leaf heads, and on top, there were alternately rows of reliefs and paintings: the former were allegories of theatre genres, and the latter depicted the image of the cloud, the sun and the night. The stage curtain was crimson, but the drapery surrounding it was yellow to match the auditorium. A state-of-the-art round horizon was built in the back of the stage, which could be used to reproduce the illusion of any sky.

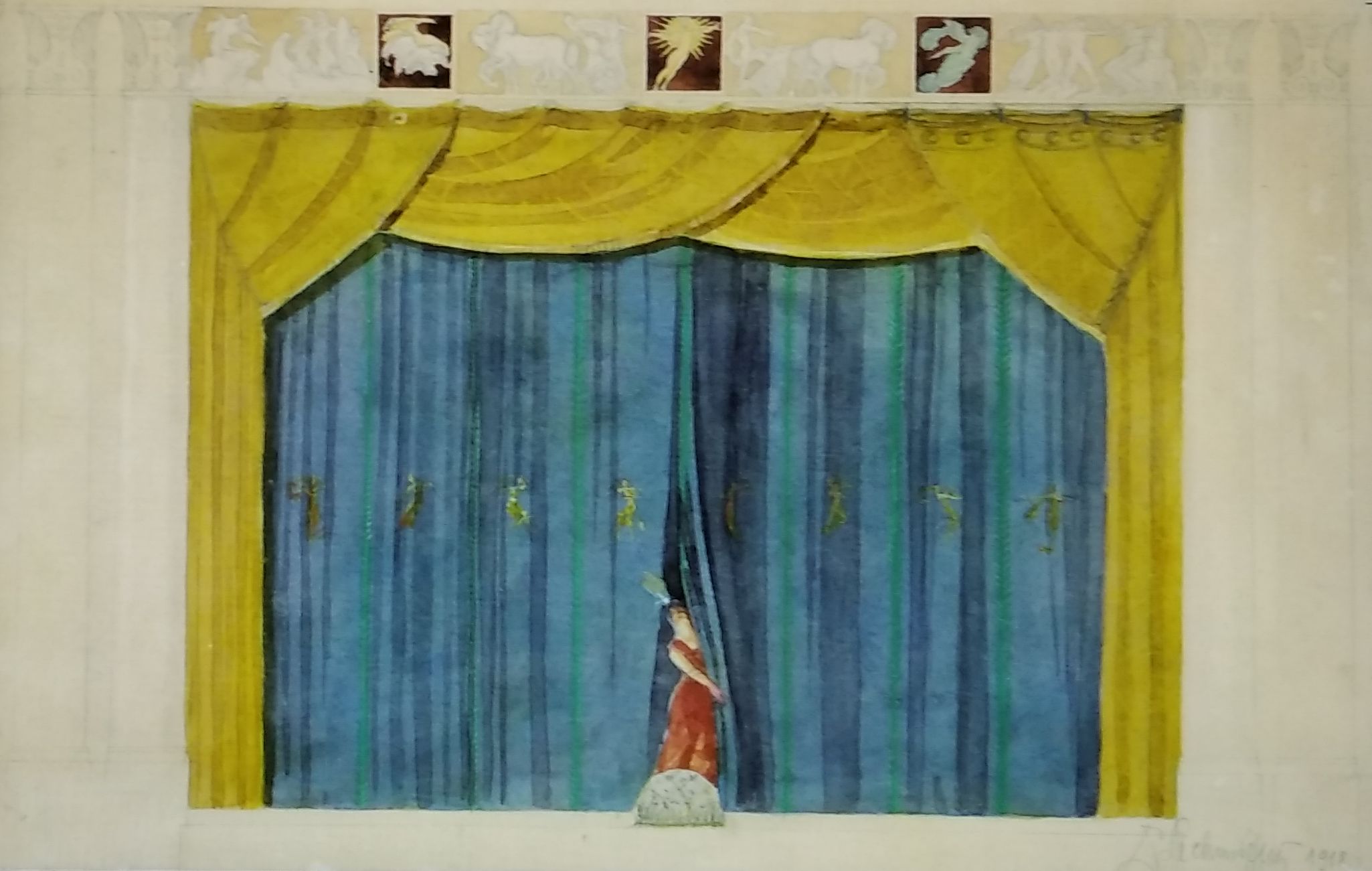

Plan of the stage (Source: Kiscelli Museum of Budapest History Museum)

Jenő Lechner also embraced his uncle's aspirations, but he saw the Hungarian architectural design language as feasible in a different way. While Ödön Lechner's wonderfully rich imagination actually created a new design language, Jenő transformed styles rooted in the past into something new with different techniques. For example, he supplemented the Empire style used here with motifs from the time of the conquest, thus giving it a Hungarian colour: he carved Ancient-Hungarian faces with braided hair into the surface of the pillars between the lodges.

The implementation of the plans took nearly a year, mainly due to wartime conditions, but was completed by the end of the year. The opening performance was held on 17 December 1918, when Émile Paladilhe's verse opera Le Passant (The Wanderer) was performed, which was followed on the same day by the drama Incidens az Ingeborg hangversenyen (Incidents at the Ingeborg Concert) and the operetta titled A háztűznéző [The Groom's Visit at The Bride]. Jenő Lechner also designed the scenery for these. Unfortunately, the Medgyaszay Theatre was very short-lived, which was caused by the chaotic political and social conditions. Due to its uneconomical status, it was already converted into a cinema in 1921: between 1921 and 1924, the Helikon Cinema, between 1924 and 1933, the Orion Cinema, and between 1933 and 1945, the Casino Cinema operated on the site of the theatre. The excellent location of the former Class Lottery Palace became a disadvantage during the siege of Budapest: it suffered extremely serious injuries, so it was demolished after World War II.

Cover photo: The Class Lottery Palace at the beginning of the 20th century (Source: Kuny Domonkos Museum, Tata)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration