He was born in Nagyenyed, Transylvania, on 6 March 1893, under the name Virgil Bierbauer. He, therefore, came from a family of German origin, in which several people worked in the construction industry. His father, István Bierbauer, was, for example, the chief technical director of the Royal Hungarian Post, and his maternal grandfather, Gyula Seefehlner, participated as a bridge-building engineer in the construction of the Liberty and Erzsébet Bridges. The young Virgil was attracted to the engineering career and his German roots at the same time, so after graduation, he enrolled at the Technical University of Munich, where he was taught by renowned professors such as Friedrich Schmidt and Theodor Fischer.

Virgil Borbíró and his wife around 1928 (Source: Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

He graduated in architectural engineering in 1915, but did not return home after that: he stayed in the Bavarian capital to obtain his technical doctorate. At that time, he was already studying art history and wrote his dissertation on the subject of the Italian Renaissance entitled Bramante and the first plans of St. Peter's Basilica, which he defended in 1920. In parallel with his studies, he already worked in Hungary, participating in the work of the National Housing Construction Committee for four years from 1918. He then opened his own architectural office and, despite the difficult economic conditions, managed to win major commissions: he designed the tourist house in Galyatétő, the Sports Hotel in Tihany (with Károly Mikle) and the Main Post Office in Kaposvár (with Pál Müller). His private life settled in 1921 when he married Adrienn Graul.

The Inner City Fire Department building in Gerlóczy Street (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

His first assignment in Budapest was for the building of the Inner City Fire Department, which he created together with Kálmán Reichl in 1925-1926. At 6 Gerlóczy Street, the inner city was enriched with a two-story classicist facade. The signs of the rather puritanical style can be observed mainly in the solution of the openings: on the ground floor, the fire engines used two wide, segmentally closed exits, and higher up on both floors, three rectangular windows were opened for the crew. On the left, a narrow projection (risalit) steps forward, the first-floor window of which is crowned by a protuberant hood moulding, and above it is a window closing semi-circularly. The main gate leading to the courtyard of the building was moved to the left, but with its lack of decoration and the semicircular design of its upper part, it was made clear that it belonged to this institution.

Virgil Bierbauer's article dealing with classicist master builders (Source: Magyar Mérnök- és Építész Egylet Közlönye, Issue 11-12, 1927)

Borbíró was not so much an engineer immersed in technical details, he looked at architecture in larger contexts. He considered it important to apply the styles based on ideals, which is why he already researched the cultural background of classicism. He gave lectures on his results at the Hungarian Society of Engineers and Architects, which he then published in the organisation's journal. From the mid-1920s, however, his attention was directed towards new styles, which he also studied thoroughly before putting them into practice.

His colleague, Kálmán Reichl, played a primary role in his break with classicism because it was through him that he came into contact with industrial architecture. They started planning the Kelenföld Power Plant together in 1925, where, at the suggestion of his partner, they applied the solutions of contemporary German brick architecture, which we now call Art Deco. However, Reichl died the following year, so the major part of the work was left to Borbíró.

The Klingenberg Thermal Power Station in Berlin (Source: de.wikipedia.org)

The decision to create the building was actually made before World War I, and a part of it was completed, but it remained unfinished due to the transition to the war economy. In the country, after the Treaty of Trianon, the investment could only continue after receiving the League of Nations loan, and the production of electricity was a pivotal element in getting the economy back on its feet, so construction received special attention. Borbíró also made a study trip to Germany in 1927, where he saw the pattern to be followed in the reddish brick facade and glazed switch room of the Klingenberg thermal power plant in Berlin. He went to The Netherlands as well, since the fruits of expressive brick architecture have been produced here since the beginning of the 20th century thanks to architects such as Michel de Klerk.

The monument building of the Kelenföld Power Plant (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

He used his experience gained abroad at the Kelenföld Power Plant, where he demonstrated his brilliant sense of style: he gave the switch room controlling the boiler houses and generators an unusually oval floor plan. This solution was partly dictated by the desire for innovation and partly by the need to create harmony between function and form. The room has become one of the masterpieces of Hungarian Art Deco architecture, thanks to its huge glass ceiling: the metal mesh of the brace also divides it into geometric shapes. The unique creation was deservedly declared an industrial monument.

The Art Deco control room of the Kelenföld Power Plant (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

During the aforementioned trips to Western Europe, he also understood the importance of functional housing construction, which was one of the main areas of application of modern architecture. After World War I, the entire continent was plagued by a housing shortage, so the proponents of the new architecture also kept social aspects in mind during their work. Bierbauer also presented what he saw abroad to the Hungarian Society of Engineers and Architects, which delegated him to the International Congress of Modern Architecture (originally known in French as Congres Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne, or CIAM for short) in the same year, i.e., in 1927.

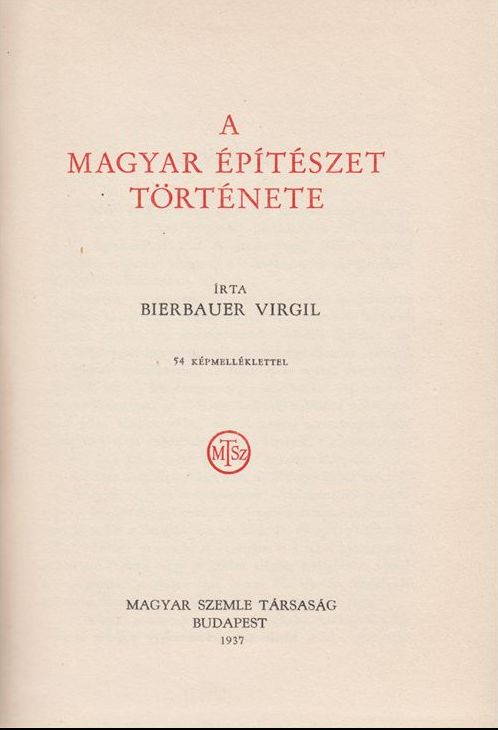

To spread modern architecture, he also used the press: in 1928, he organised the supplement of the magazine Vállalkózók Lapja into an independent magazine called Tér és Forma. In it, he gave news about the latest developments of Western European modernism and presented the principles of one of the main advocates of the movement, the Swiss Le Corbusier, but stated already in his first article that he did not agree with him on everything. He accepted the five points he formulated, which modern buildings must follow - floor plan adapted to function, free shaping of the facade, sash windows, standing on legs, flat roof - but he was not so radical and considered the construction of smaller family houses instead of huge blocks of flats to be the way to go. In addition to editing Tér és Forma, the masterpiece of Bierbauar's literary work is the opus The History of Hungarian Architecture, which was published in 1937 and was the first to discuss the topic comprehensively.

Virgil Bierbauer: The History of Hungarian Architecture, 1937

He was also at the forefront of organising the 12th International Congress of Architects, which was hosted in Budapest in 1930. It was here that the idea of creating a model housing estate based on German examples arose, which was realized the following year in Napraforgó Street in the 2nd District. Bierbauer not only took a key role in organising the construction, but he also designed the villa under number 4. On this one-story building, he already displayed the tools of modern architecture.

Villa at 4 Napraforgó Street (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 10, 1932)

His expertise in organisational tasks, as well as his excellent ability to understand large contexts, quickly turned his interest towards urban planning tasks. He took part, for example, in the tender for Erzsébet Avenue, which was supposed to regulate the sprawling Erzsébetváros, in which they were looking for the best plan for the inner city estuary (1930). At the beginning of the 1930s, the establishment of a National Stadium, which he envisioned together with Bertalan Árkay on Aranyhegy, was a topic that concerned many. Their large-scale plan was presented in 1933 at the first urban planning exhibition held at the Gellért Hotel, whose organisational tasks were also performed by Bierbauer.

He achieved his greatest success in 1936 when he won first prize in a tender for the arrangement of the Buda bridgehead of the Horthy Miklós (today's Petőfi) Bridge. The following year, a similar competition was announced for the Óbuda (today's Árpád) Bridge, in which he also participated. His recognition is indicated by the fact that several rural towns asked him to prepare their urban development plans in the late 1930s and early 1940s (for example, Vác, Komárom, Nagybánya, Tata).

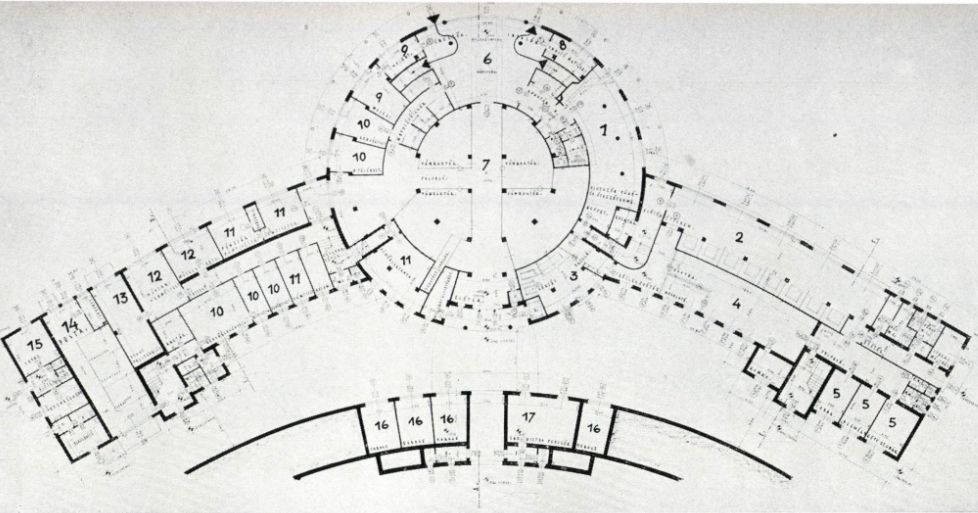

Floor plan of the traffic building of Budaörs Airport (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 8, 1937)

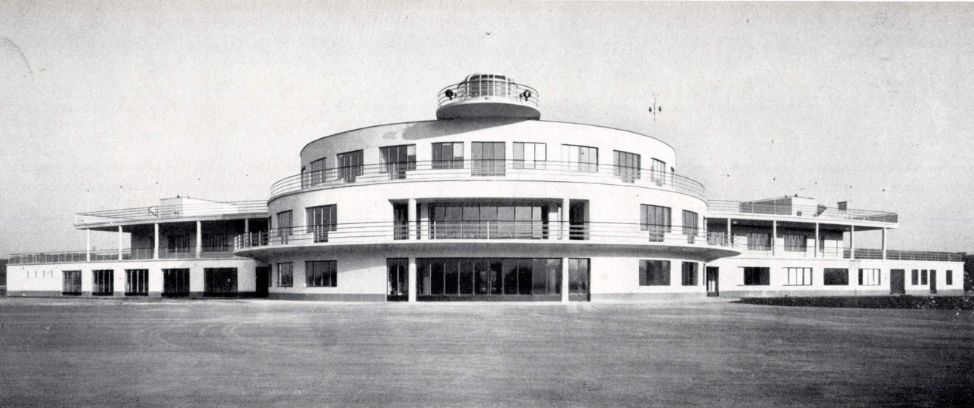

He was commissioned to design the traffic building of Budaörs Airport through a tender, and together with László Králik, he managed its construction during 1936-1937. The building, which can be classified in the category of streamlined architecture, also expresses its function with its forms, in the press of the time it was presented as if a snow-white aeroplane had landed among the hills. The analogy is apt: the central, curved front-to-back building block could be the fuselage of an aeroplane, to which two narrow but long wings are connected. The core of the building is three-storeyed, the floors draw a semi-circular arch and step back with terraces, but the control room at the top still extends slightly forward. The middle tract includes the spacious admissions hall, the right-hand wing contains the rooms related to the general public, and the left-hand wing contains the service rooms.

The curved facade of the airport's traffic building (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 8, 1937)

In World War II, despite his relatively old age, he could not avoid military service and was sent to the front in December 1942. He survived the siege of Budapest already in the capital, at which time he changed his name to Borbíró. However, his attitude did not change: he continued to take on an active role in organising and public life. He was a member of the Budapest Public Works Council, and in 1948 he was elected a corresponding member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

He also got a taste of politics, and between 1947 and 1949 he worked as state secretary for construction in the colours of the National Peasant Party. In the year of the communist takeover (1949), he was pushed out of public life for this reason, but he did not remain without work: he got a job at the Department of Architecture of the College of Fine Arts. After that, he also worked at the National Construction Office, but in the meantime, he also wrote a book, which was published in 1953 under the title Proposals for the Urban Planning of Budapest. As a result of the strained pace, he died at the age of sixty-three on 25 July 1956.

Cover photo: The traffic building of Budaörs Airport (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 8, 1937)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration