Where the Grand Prince was buried remains an open question to the present-day. In the Gesta Hungarorum, the anonymous author wrote that Árpád was laid to rest near the source of a stream, which then flowed towards the "the city of King Attila" in a stone channel. The author also mentions that a church named "White" was constructed at the site under the patronage of the Virgin Mary after Hungarians converted to Christianity.

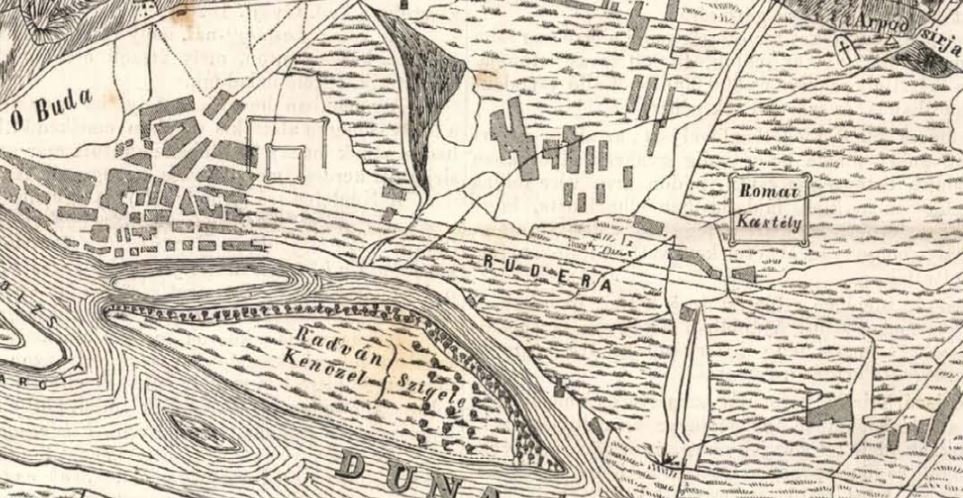

The medieval ruins of the Fehéregyháza ('White Church') built above the tomb of Prince Árpád were likely found in the second half of the 19th century in Óbuda (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság 13 June 1880.)

When the millennium of Árpád's death came about in 1907, the ruins of what were thought to be the White Church mentioned the Gesta Hungarorum were well-known. The ruins were the remains of a Pauline Monastery close to the junction of Bécsi Road and Vörösvári Road, not far from the Victoria brick factory that was founded in the 19th century.

Records show that King Matthias founded a Pauline Monastery next to White Church. After the ruins were found in 1869 Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy visited the site, as did Franz Joseph himself. While the remains of the pine were never found, at the time it was believed that a mystery of Hungarian national and patriotic remembrance had been solved.

As mentioned above, 1970 was also the 40 year anniversary of Franz Joseph's ascension to the throne, and Act XXVIII. of 1907 passed in honour of this stated that the Church that once stood at the final resting place of Prince Árpád must be rebuilt. The exact location, however, was not a primary consideration.

There was a strong national desire to mark the memorial site in some way. Thus the location was not only influenced by academic and scientific facts. An anecdote about Sándor Wekerle emphasises this. When Franz Joseph, who donated 600,000 Crowns to the construction of the Church, asked the prime minister where Árpád's grave actually was, Wekerle replied: "Árpád will be buried, where Your Majesty wishes him to be."

Nevertheless, Tamás Guzsik, a prestigious researcher of medieval Pauline architecture, believed that the ruins in Óbuda were indeed the remains of White Church. Sadly, the past tense indicated that the ruins unearthed by Lajos Némethy, Titusz Tholt, Imre Henszlmann and Ernő Foerk were destroyed after the excavations.

However, the loss of the ruins did not affect the planned construction. Decision-makers at the time understood the reconstruction to mean the creation of a completely new church, in the spirit of the Middle Ages, and in line with the dominant style of the period: historicism. In this regarding, commissioning Frigyes Schulek was almost beyond question, and the ageing master architect was tasked with planning the memorial.

Schulek's career was full of medieval connections: he had restored and rebuilt real mediaeval churches, designed buildings in the neo-Romanesque and neo-Gothic styles. His experience was thus a guarantee that that the memorial site would be worthy of prince Árpád.

Implementation of the grand plans laid out in 1907 did in fact begin but progressed slowly. The first world war further slowed efforts. The Magyarország daily newspaper published a detail report of the planned memorial site on 22 September 1916: "A report from the Public Works Council of the Capital claims that outstanding questions in connection to the construction of the memorial have been resolved. Necessary expropriations are being carried out by the Public Works Committee, while the memorial will be designed by the respected architect, Frigyes Schulek."

Citing the Technical Department of the Public Works Council, the newspaper presented plans for the site in more detail. The memorial was to be built in a large trench between Bécsi Road and the Óbuda Old Cemetery (which has since been removed). A serpentine road would have lead up Tábor Hill from Bécsi Road, where roughly 30 metres above the road a "church-like memorial" would have stood in the centre of a large park.

The memorial would have included a monument to the Seven Chieftains with six smaller, 9-metre tall obelisks encircling an 18-metre high obelisk symbolising Prince Árpád.

The Church planned by Schulek would have lain above the obelisks to the north on a plateau fortified with a bastion. The Romanesque Church would have had a lookout tower and a so-called gatehouse.

As at the time the spring mentioned by Anonymus was at the time considered to be the source of the stream used by the Rádl Mill, plans were also made to construct an ornamental fountain above the spring.

According to the final version of the plans, which according to press reports, Schulek also created as a plaster model, the Church itself would have had a central floor plan, with side chapels surrounding it. The architect aimed to plan a building in line with 9th and 10th-century architecture. In its style, among completed buildings planned by Schulek, the Memorial Church would have been similar to the Fisherman's Bastion and Szeged Cathedral. Its central dome would have towered above the building and been crowned with a cross at the height of 31 metres.

In a memorial speech given for Frigyes Schulek at the 22 March 1922 sitting of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Gyula Foster also mentioned the plans for the Árpád Memorial Church: "[Frigyes Schulek] took up the task with great enthusiasm and presented both his plans and the required budget. The Committee believed that the plan was among the architect's best works, and recommended that its construction be carried out to the Prime Minister, who accepted their recommendation. Tenders were also held to for the construction were also held, which would have allowed work to commence, had not the World War broken out. Sadly, it seems that similarly to the case of the Queen Consort Elizabeth memorial, the conflicting views on the location of the memorial, and lengthy preliminary negotiations blocked landscaping and construction work from beginning. Today, there is little hope for the Árpád memorial t be completed in the spirit of the law. Thus, our capital has lost a masterpiece by Schulek."

Thus, only six months after Schulek's death in 1922, the failure of the plan was considered a fact. Looking at the historical circumstances, this was to be expected. The defeated country was in a terrible state and work on Szeged Cathedral, where construction began in 1913 only continued in 1923 after being interrupted by the war.

However, the plans for the Árpád Memorial Church were not completely thrown aside. Nothing was built on the land, and in the 40s the Public Works Committee again planned the landscaping of the park to prepare it for the memorial site. These plans never came to fruition. Disaster followed, and the signs of war reached Budapest. At the end of World War II, a gathering camp for those convicted to forced labour operated within the still functioning brick factory.

The new world order after 1945 sealed the fate of these plans. The location where Schulek dreamt a magnificent memorial and Church has now been entirely built up. The majestic Church and memorial to honour Árpád and the Hungarians that settled in the Carpathian Basin has thus remained a missed opportunity of Hungarian art. Nevertheless, looking back over the past century, there are several reasons why the nation was unable to complete the stunning plan, which would have been a significant work by the great architect Frigyes Schulek.

Cover photo: The Árpád Memorial Church from the south on Schulek's plans from 1912- (Source: BHM Kiscell Museum – Modern Urban History Collection

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration