The closure of the Kós Károly Promenade and the banning of cars from the City Park has been decided. This fulfils a long-standing need of citizens: around the fall of socialism, many people suggested that car traffic through the park should be restricted.

City Park is a popular place for rest, entertainment and excursions for the capital's residents. Even though the former main street of Pest, Király Street, led here, the big country roads avoided this area. The Avenue, today's Andrássy Avenue, was not built to be one of the city's main transport routes, i.e., it was not an urban section of a national highway, but a representative, elegant, the palace-lined avenue that started and ended within the city: it had no continuation outside the city limits.

That is why the city’s leaders in the 1890s did not allow the road to be marred by trams, even though they knew that the millennium celebrations planned for the City Park would have to be served by public transport somehow. The solution became the Millennium Underground.

Andrássy Avenue did not end in Heroes' Square but on the other side of the park. The road bypassed Heroes' Square, crossed the bridge built in 1896, and then crossed Hermina Road and collided with the more modest Hungária Boulevard and the railway. The road through the park did not have an independent name, it was called the outer Andrássy Avenue, and then, after World War II, outer Népköztársaság Road.

Bikers in 1930 in front of Vajdahunyad Castle (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 20282)

There were ideas to extend the road: the Budapest Public Works Council had already drawn up a plan in 1932 to build Andrássy Avenue to Rákospalota, but even then, the aim was not to allow transit traffic through the city on this route.

Even though cars, parking lots and races have always been allowed in City Park, high traffic appeared in the park when the M3 motorway and the interchange over Hungária Boulevard and the railway were built.

PestBuda collected why some of the traffic on the M3 motorway was diverted to one of Budapest's public parks. In the 1960s, the planning of the national motorway network began, as part of which Hungária Boulevard was intended to play the role of a motorway ring road, which would have connected the roads starting from Budapest. In addition, some of Budapest's main roads were to be developed into internal expressways, and this fate was intended for Népköztársaság Road too. It is true, at least it was not imagined as an urban highway, like Rákóczi Road, but definitely, as one on which transit traffic passes through the city.

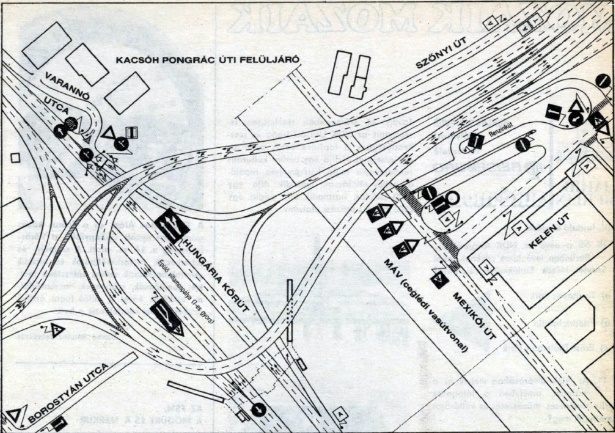

Traffic regulations of the Kacsóh Pongrác Road interchange (Source: Autó Motor, 15 February 1987)

The direction of the M3 motorway to the northeast was marked on a route other than Route 3. The new route was imagined as a continuation of the avenue called Népköztársaság Road. A huge motorway interchange was planned at the crossing of Hungária Boulevard and the outer Népköztársaság Road.

This interchange remained on the agenda even after the new Budapest transport development concept adopted in 1978 meant that Hungária Boulevard was no longer the ring road to connect motorways but the planned M0 motorway. However, Hungária Boulevard remained an important main road, and the M3 motorway branching out from here remained part of the national expressway network plans, as did the overpass system serving new traffic needs.

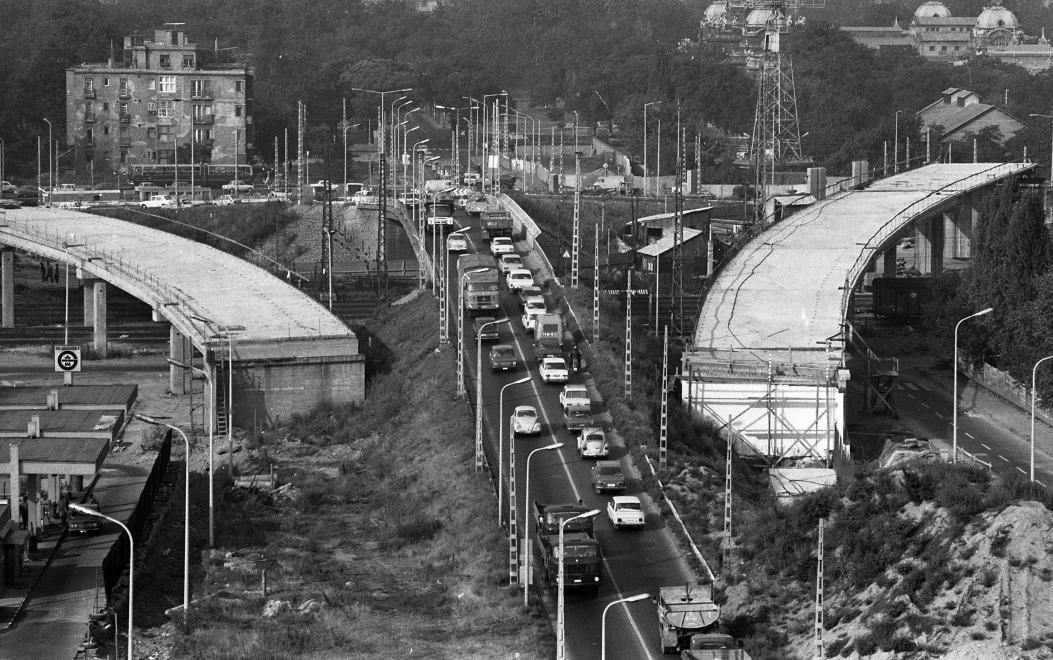

The interchange under construction in 1980 (Photo: Fortepan, Magyar Rendőr)

The first 23.5-kilometre section of the M3 was opened in October 1978. The new overpass on Hungária Boulevard was completed 5 years later, when the former narrow overpass, which only spanned the railway, was expanded, and the motorway interchange, which is visible today that led the traffic of the M3 motorway to Hungária Boulevard and Népköztársaság Road through City Park was completed.

Motorway interchange on the edge of City Park in 1984 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 151842)

After this overpass system was completed, the part of the Népköztársaság Road passing through City Park was renamed Kós Károly Promenade. Quite ironically, this route became a promenade in name when they led unprecedented car traffic through it.

In the eyes of the contemporary decision-makers and, in fact, the people of Budapest, the fact that cars appeared in City Park did not seem to be such a big problem because City Park had not been closed to traffic before. Cars were parked there, and the area even hosted car and motorcycle races. Races were held in City Park from 1926 until the 1970s, during which racing cars and motorcycles used the Liget’s inner roads.

City Park also emerged as a possible location for the Formula 1 track in Hungary. A route longer than 4 kilometres could have been created in the City Park, while the pit lane, the finish line and the necessary infrastructure would have been located at the Felvonulási Square.

However, City Park was full of cars regardless of the races, as the Felvonulási Square had been used as a car park since the 1960s, as had the Liget’s inner road network, to which was added the not insignificant traffic of buses to the Zoo, Amusement Park and museums.

Motorbike race in 1949 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 33011)

After the fall of communism, green voices intensified, and environmental organisations questioned the need to lead the M3 through City Park. That is why, barely ten years after the opening of the overpass, in April 1994, the traffic organisers of the capital tentatively closed the Kós Károly Promenade. The aim was to examine the impact of the closure of the promenade on the surrounding streets. The data summarized for October showed mixed results: not surprisingly, with the diversion of traffic, the level of air pollution shifted elsewhere, although the pollution itself did not decrease overall. At the time, it was calculated that the complete closure of the road could not take place until Hungária Boulevard, the M0 and Rákóczi Bridge were completed, at most, the Kós Károly Promenade could be closed intermittently on weekends.

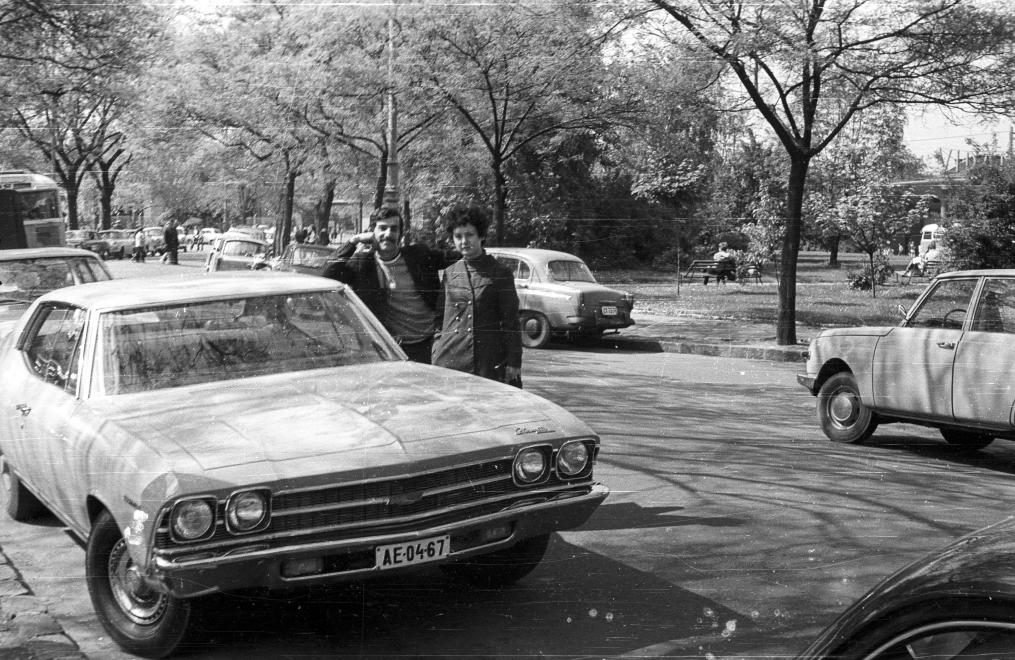

Cars in the City Park in 1970 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 70621)

Today, these conditions have been met, and the approach to transport management has changed. The current decision is also one of many that try to correct the one-sidedness and mistakes of the previously unfavourable, car-only traffic order.

Cover photo: Buses in front of the Amusement Park in 1975 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 77818)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration