However, in 1869 the state made an offer to buy the Chain Bridge Company, as it was known. Representatives of the Government and the company began a series of talks that lasted into 1870 and resulted in the state buying the company and accepting all debt at a price of 690 HUF per share.

The State purchased a total of 9816 shares for a total cost of 6 733 040 Forints (the construction of Margit Bridge at the time cost only 5.2 million). Alongside buying the bridge, the state assumed the debt of the company, totalling 1 386 400 Forints and the 200 000 Forints compensation owed to the cities of Pest and Buda (to be paid in 1931 and 1936 respectively) and the 12,000 Forints yearly interest on each.

Why did the state need to make the deal? Why could the bridge not remain in private hands?

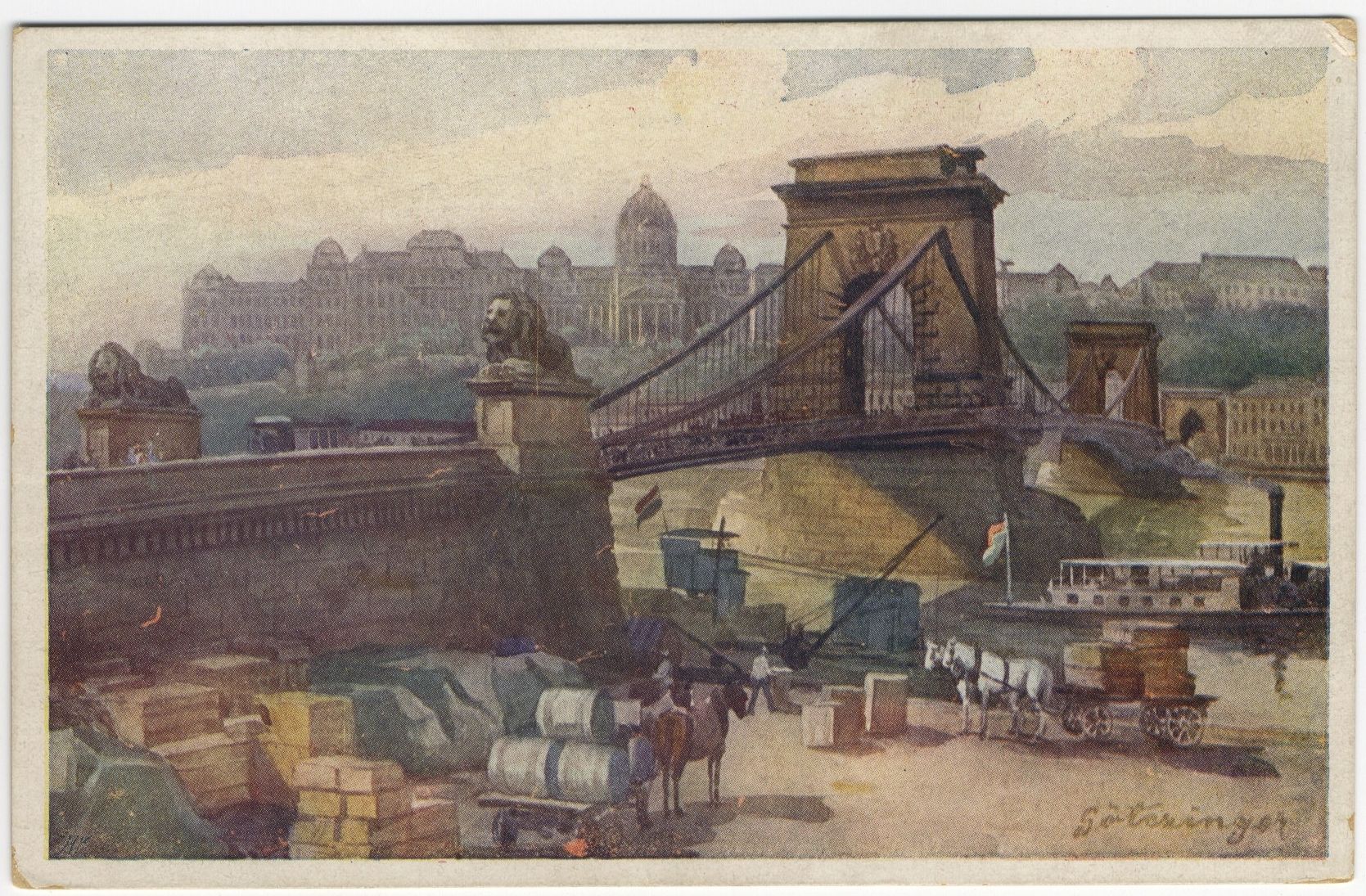

Chain Bridge on a coloured postcard from the 19th century (Source: The Hungarian Museum of Science, Technology and Transport, archive no.: KPLGY 2498.1)

The Chain Bridge was purchased for several reasons. The most important of these was that the State wished to revoke the privileges provided to the company that built the bridge and to ensure that it could not block future plans for development.

The Company actually held the right to control all crossings between Pest and Buda within the limits of the two cities, including ferry and other boat crossings. This meant that the State could not have built another bridge over the Danube without the permission of a private company and would have also had to pay a commission to the company from the crossing tolls it collected on other bridges.

Furthermore, the Government needed the income the bridge provided. The State had taken a sizeable loan to develop Budapest. The 24 million forints were covered by a series of income sources, one of them being the tolls collected on Chain Bridge. Strangely, the Government used the loan itself to purchase the bridge.

The pennies paid as a toll to cross the bridge became a major source of income for the State after 1870. The man carrying a bag on the picture paid more to cross than those unburdened. (Source: The Hungarian Museum of Science, Technology and Transport, archive no.: KPLGY 2017.121.1)

Shareholders in the company were less lucky. Until the 1860s, maintaining the company made no profit. The value of the company’s shares only grew above their nominal value in 1868 and in the 1850s were worth only 60% of their par value. And while shareholders were entitled to 4% dividends per year, they were never able to take more out of the company until the middle of the 1860s.

Thus, when the plan to buy the shares became public, the Government was accused of supporting shareholders and saving them from a bad investment. Furthermore, some members of the government also held a stake in the company. Today, this would at least be a conflict of interest but may even be considered insider trading.

As a result, the negotiations were led by György Festetics, the minister beside the King (the minister responsible for supporting Hungarian foreign policy in the Habsburg court), instead of Menyhért Lónyai, minister of finance, despite the latter having more oversight in the matter. Lónyay, however, had a large stake in the deal. Not only did his father-in-law and later wife own shares in the Chainbridge Company, Lónyay himself was one of its Directors.

The minister beside the King provided regular updates on the negotiations. The Government first offered 643 Forints and 63 krajcárs (pennies) per share, while the company demanded 750. Talks fell apart for a while after the original offer was rejected. Later the Government increased its offer to 660 Forints, a number also rejected by the company. Later, Festetics informed the Government that he had been privately informed that the company would accept an offer of 690 Forints per share. Sadly, no notes remain of whether Cabinet members simply smiled or turned to the most probable informant, Lónyay, who was also sitting in the room after this information was shared.

From 1870 the State could collect tolls on boat crossings as well, a right secured with the purchase of the Bridge. (Source: The Hungarian Museum of Science, Technology and Transport, archive no.: KPLGY 1205.1)

The negotiations lasted just over a year and were closed on 3J June 1870, when the Chain Bridge Company accepted the Government’s offer of 690 Forints per share. The Chain Bridge became the property of the State on 1 July 1870. The shareholders made a rather good deal with the offer, as the nominal value of shares was 500 Forints.

Many hoped that state ownership would lead to the bridge toll being lowered or even scrapped. However, the Government continued to collect the tax. The Government only lowered the toll 15 years later, from 1 July 1885, halving the pedestrian toll (only those crossing from Pest to Buda had to pay), but raising the toll for heavy traffic above the price of crossing on Margit Bridge to push traffic out to the new bridge. (Henceforth, the Government would also use a part of the collected bridge tolls to build new bridges.

There were no major political debates around buying the Chain Bridge. All political parties not only accepted it but saw it as the key to further developing Budapest. Even Ferenc Deák, one of the most influential politicians of the period, supported the deal. In the parliamentary debate of the legislation allowing the purchase, he said:

“Without buying the bridge – as the contract stipulates that no other bridge may be built – not only can the two cities not be connected, but nor can the railroads on the two sides of the river.”

Thus, the Chain Bridge entered State ownership, and the Government gained the right to build further bridges across the river and within a few years, Margit Bridge was completed.

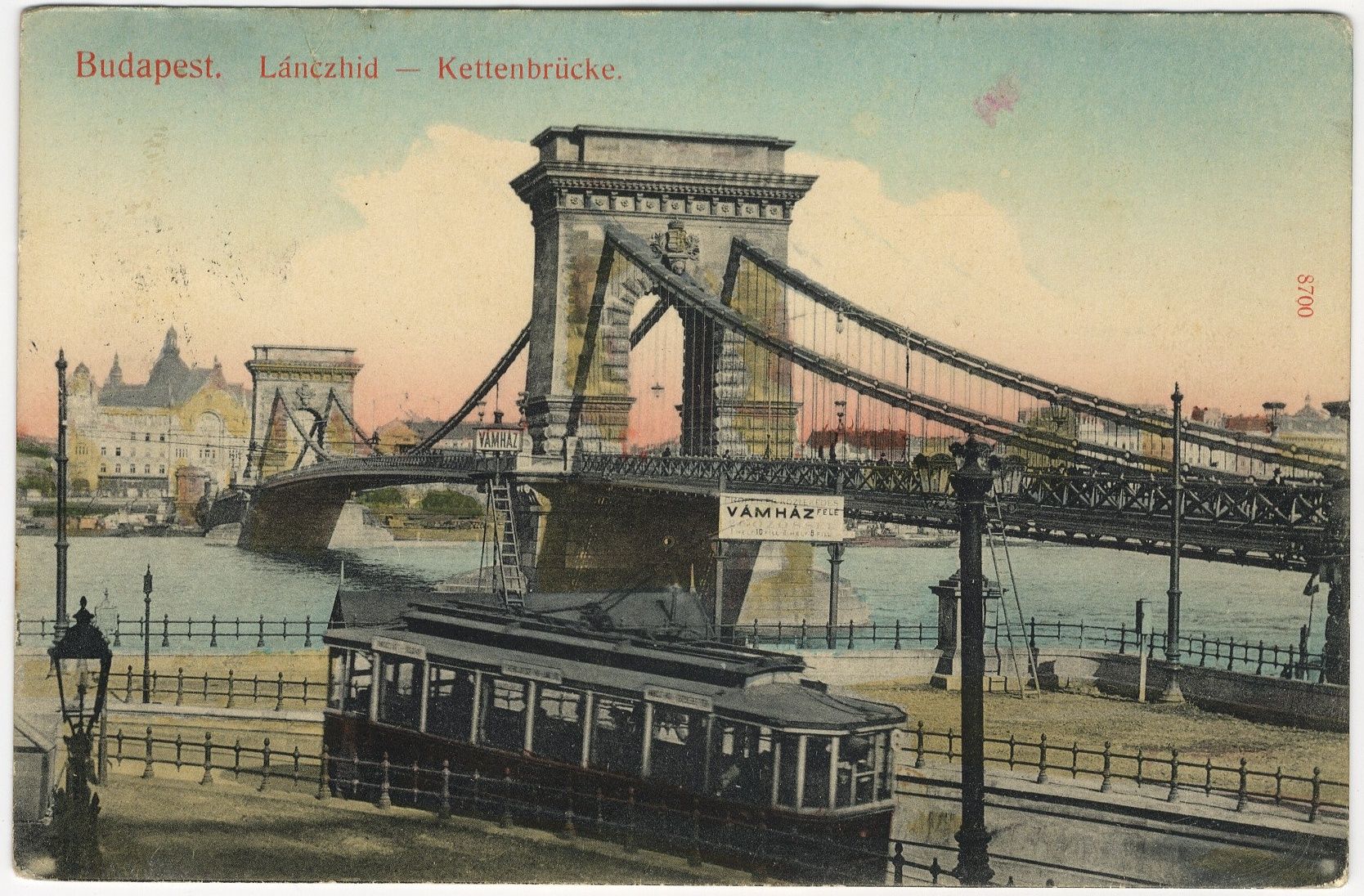

Cover photo: The state-owned Chain Bridge at the turn-of-the-century (Source: The Hungarian Museum of Science, Technology and Transport, archive no.: KPLGY 2017.536.1.1)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration