Towards the end of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th, an incredible amount of river regulation and flood prevention work was completed in Hungary. Overall, two million hectares of land were protected from floods. The Budapest flood defence system was also built in the period, which not only meant the construction of the embankments but a slew of further projects.

One of these was narrowing the Danube, not only by filling the riverbed but by simply cutting one of its branches of from the main river. The dam built to achieve this ran in line with the present-day Gubacsi Bridge. However, the changes caused several problems. The river branch closer to Soroksár became innavigable and turned into a swamp, becoming a hotbed of infectious diseases.

Jenő Kvassay (Buda, 1850–Budapest 1919) (Photo: József Udránszky/A Magyar Mérnök- és Építészegylet Közlönye. 1919 issues 22–28.)

However, in the last two decades of the 19th century, an engineer who viewed his tasks through a long-term, national perspective took over Hungarian water management. This was Jenő Kvassay. It was under his leadership that the Soroksár-Danube was given new life. The old dam was demolished, and a new lock constructed at the northern end of Csepel Island.

The new lock made the Soroksár-Danube navigable again. Kassay also recommended constructing a micro-hydroelectric power plant next to the lock, which took advantage of the fact that the water level was lower in the Soroksár branch than the main river.

Aerial view of Kvassay Lock, Kvassay Bridge and Kvassay Road (Photo: Fortepan, Hungarian Air Force, 1944.)

After graduating from the University of Technology, Jenő Kvassay gained professional experience abroad before returning to Hungary in 1878. At the age of 28, he was tasked with creating and managing the agricultural water service, the Cultural Engineering Institute, the creation of which he himself had proposed. From 1889 he became the head of the organisation established to unify water management in the country, the National Office of Hydraulic Engineering and Soil Improvement, and from 1899 headed its successor, the National Hydraulic Engineering Directorate.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Kvassay turned his focus to waterways. HE took significant technical and diplomatic steps to ensure that Budapest becomes a central stop of the international Danube waterway. To achieve this, he recommended the construction of a new winter and new permanent port – which became the Csepel Free Port. He proposed launching Danube-based sea navigation in 1916.

Kvassay was introduced with the following words by a report of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences when he was awarded the Wahrmann Prize:

"Jenő Kvassay is one of the countries leading experts. His widespread publications hve been awarded th hgihest prizes by the Academy twice already. The large cultural engineering organization was created based on his recommendaton and with his assistance, and continues to operate successfully under his leaderhsip. He drafted the 1885 Water Act. He has worked for the financial betterment of this nation throughout his life with great zeal and commitment, and looks not for material rewards, but finds these in the results of his work."

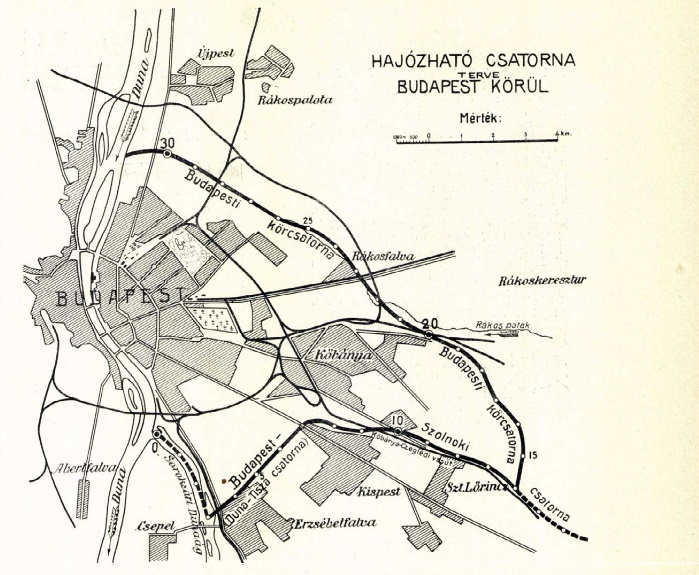

Had one of his biggest plans been completed, it would have fundamentally changed the layout of Budapest. In a paper published in 1912, Kvassay presented the plans of a navigable canal that encompassed Pest. However, the canal would have run further from the city centre than Reitter's popular plans from the 1860s.

Kassay envisioned two canals. The first would have started from the Soroksár-Danube near the present-day Gubacsi Bridge and connected Budapest to Szolnok, creating a navigable Duna-Tisza canal. The other would have connected to this around Pestszentlőrinc. The second branch would have started above Margaret Island and roughly followed the path of the Rákos Stream to the southeast.

The Budapest Ring Canal would have been 17,5 km long, while the section of the Duna-Tisza canal leading to the meeting point of the two would have been 11 km. Along the total length of the 28.5 km canal, the elevation would have been 34 m. The difference would have been overcome by a series of four locks in the valley of the Rákos Stream and five locks from the Danube to Kőbánya.

Kvassay estimated the construction costs at 30 million crowns, not including the cost of expropriated land. Nevertheless, he calculated that the investment would have returned simply from the increase in the value of these plots without any direct income.

The canal route proposed by Jenő Kvassay. The eastern branch would have roughly followed the path of present-day Rákospatak Road – Keresztúri Road – Maglódi Road, while the southern branch that of Határ road and the Expressway leading to Ferihegy Airport (Source Vasárnapi Újság, 1912. issue 45)

The plan was never implemented because of World War I. After the war, the severely ill Kvassay retired and died in June 1919.

The Kvassay Lock in 1927 (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection). Even 1000 ton barges could pass through it.

In 1920 a memorial committee formed, which requested that the Minister of Agriculture name a meaningful feat of hydraulic engineering after Jenő Kvassay. The minister chose the Soroksár Lock that was being constructed at the time. Later, the Council of Public Works accepted the memorial committee's recommendation to name the road leading to Csepel after Kvassay, just as the bridge built as a continuation of the road was also named after him in 1927.

Cover photo: The Kvassay Bridge in 1950 (Photo: Fortepan, Uvaterv)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration