The most defining trend of 19th century Hungary was historicism, i.e. the simultaneous use of historical styles, which was typical during dualism (1867-1918). Historicism also used the forms of antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Modern Age, the most popular being the Neo-Renaissance style, which still defines the image of the capital to this day. Neo-Gothicism also played a major role, although due to its religious connotations, it can primarily be observed in church buildings.

Neo-Gothic is not to be confused with Gothic Romanticism, which was more prevalent between 1840 and 1860. The difference between the two is that while in Gothic Romantic buildings, only the decoration is medieval, a Neo-Gothic structure is also characterized by a greater degree of loyalty to the style. (The diverse style of historicism is also called eclecticism, although due to its pejorative connotations, art historians now avoid the term.)

Matthias Church, or in its official name the Church of the Assumption in Buda (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

One of the symbols of Budapest, Matthias Church, which is also popular with tourists, or the Church of the Assumption in Budavár, was restored during the period of dualism. As mentioned, Neo-Gothicism came to the fore in connection with ecclesiastical constructions, but this building showcases more than the religious nature of Neo-Gothic architecture. The church has a significant medieval history. Its structural core was built after the Mongolian invasion. In addition to its poor condition, it was renovated for two reasons: on the one hand, in the second half of the 19th century, there was a lively interest in monuments and the need to restore them arose. On the other hand, in 1867, Franz Joseph was crowned King of Hungary in Matthias Church, and this also helped to start the renovation program.

One of the symbols of Budapest, Matthias Church, also a popular tourists sight (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Pál Lőveioffers most insight into the works. The restoration was confirmed in 1873, and work began in 1874 and lasted until 1896. The reconstruction of the building, which was rebuilt several times during the 14th–15th centuries and was also used as a mosque during the Ottoman Era, was a great challenge for Frigyes Schulek, who prepared the plans and began his work with a large-scale excavation and research. (His notes serve as an important point of reference for researchers to the present day.)

Szentháromság Square and Matthias Church as seen from Szentháromság Street, before the reconstruction. Photographed around 1874 (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Capital Archives HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.079)

As a first step, he demolished the 18th-century Jesuit buildings encircling the church to achieve a monumental effect through its free-standing position. As a second step, he removed the baroque furnishings of the church, which to today's eyes, seems a very drastic solution, but was maximally in line with the purist (i.e., only considering the original state) method of restoration. During the excavations, he found the building to be in very poor condition, so most of the perimeter walls and vaults were completely rebuilt.

Reconstruction of Szentháromság Square and the Matthias Church by Frigyes Schulek. Photographed around 1893 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 116770)

Szentháromság Square and Matthias Church seen from Trinity Street. Photographed (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.08.053)

The aim of the reconstruction was to restore the 16th-century condition of the building, and the current style of the building is adapted to this. He tried to keep the original carvings found inside. If this was not possible, he replaced them with faithful copies. (The original elements are now stored in several institutions.)

Matthias Church, church interior, opposite the frescoes by Charles Lotz. Photograph from around 1896 (Photo: Fortepan / Budapest Archives HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.08.018)

The upper section of the most characteristic element of the main façade, the high south tower, was completely rebuilt by Schulek, with its spectacular carvings and steep stone steeple can be seen from afar. The beautiful rose window, also on the main façade, was made according to the architect's plans, but his drawings were based on fragments found on site. Closely related to the external appearance and the character of the building is the colourful and patterned roof covered with Zsolnay ceramics.

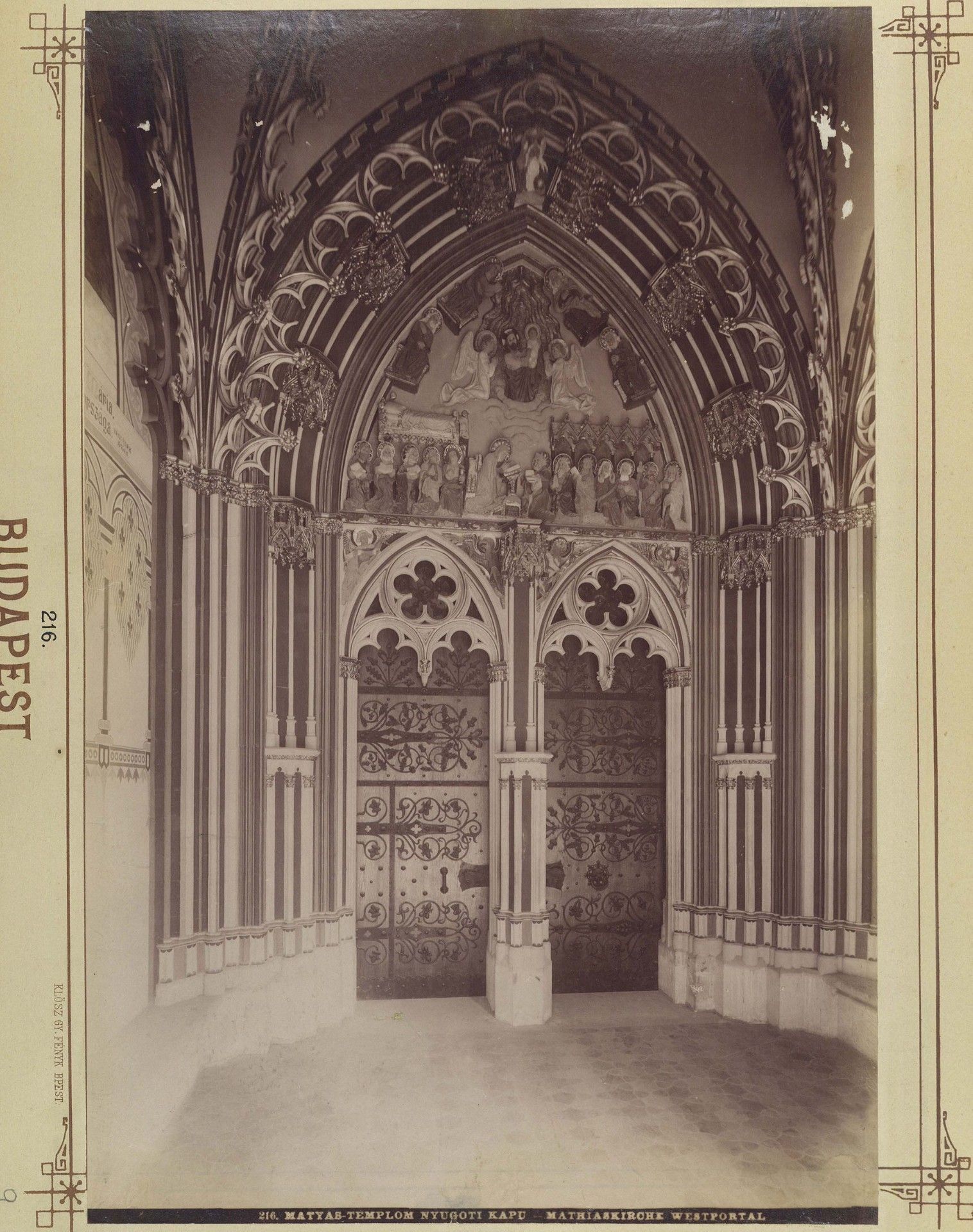

Matthias Church, the inner forecourt of Mary's Gate. Photographed around 1896 (Photo: Fortepan / Budapest Archives HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.08.017)

The colours and style of the interior harmonise with the exterior. Through their colourful paintings and carved furniture, it is the most important piece of Hungarian applied art of the period. The wall decorations, the patterned floor covering and the Gothic furniture were also designed by Frigyes Schulek himself, the windows were designed by Bertalan Székely, Károly Lotz and Károly Tóth, with Ede Kratzmann manufacturing them. The historical scenes decorating the walls and the paintings depicting saints are also the works of Bertalan Székely and Károly Lotz.

Matthias Church, nave, opposite the sanctuary and the altar. Photographed around 1896 (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.08.021)

Although Frigyes Schulek carried out the restoration with a purist restoration approach of his time, he did a surprisingly thorough job in his research compared to his contemporaries and tried to preserve as many original details which was not typical in the era. As a result of his large-scale historizing plan, a truly high-quality work was created.

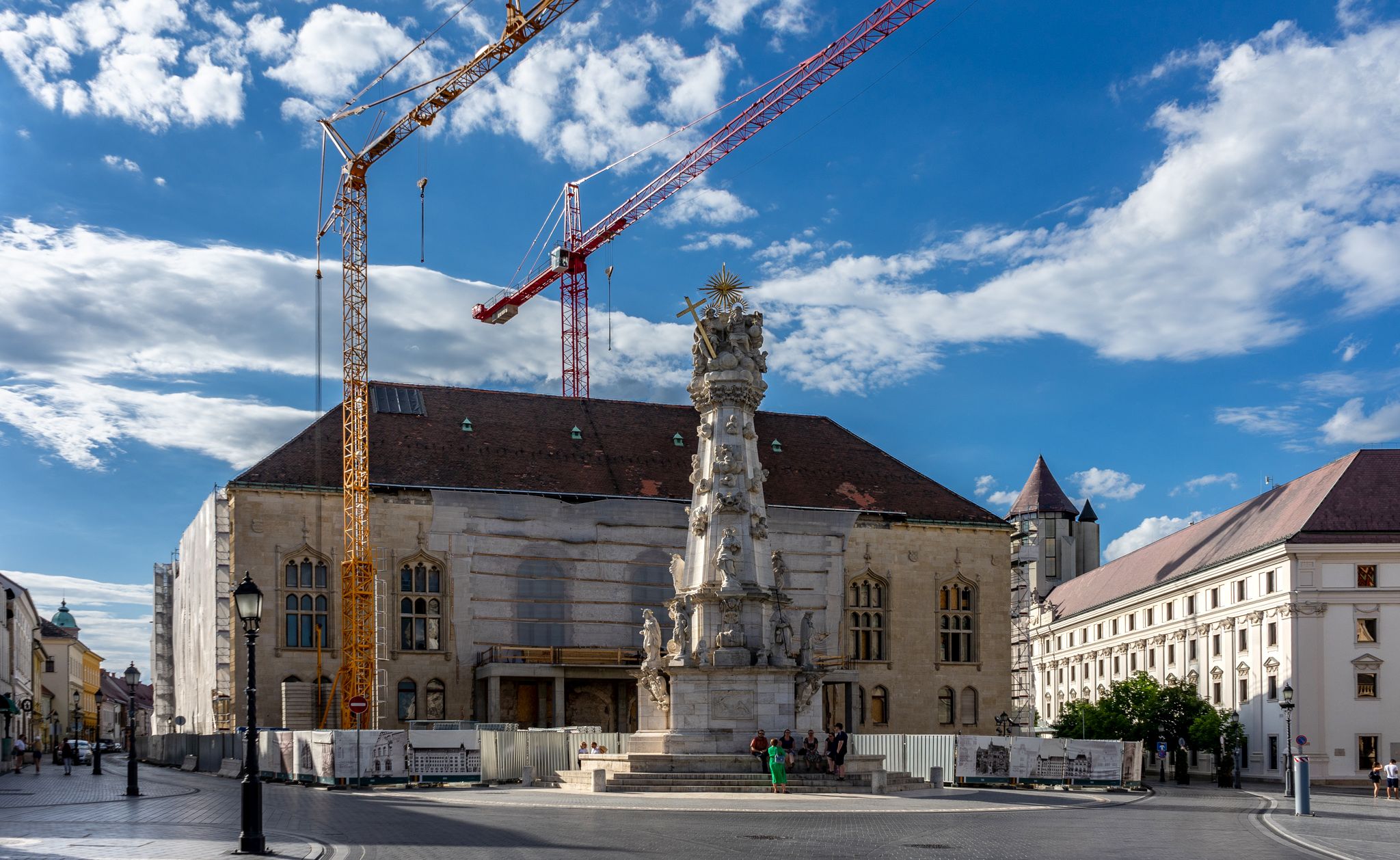

One of the main works of Sándor Fellner stands next to Matthias Church, on Szentháromság Square, and will soon serve as the Ministry of Finance again. Fellner's oeuvre was dealt with in-depth by József Rozsnyai and Tibor Gottdank, and their studies are the best source of information about the building. The Ministry of Finance is an excellent example of non-ecclesiastical neo-Gothic architecture.

Szentháromság Square, Ministry of Finance in the background in 1934 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 134536)

There were two reasons for the choice of style. One was the style of the neighbouring Matthias Church, to which the architect wanted to conform. The other is less clear yet typical of the era. The Gothic style is very authoritative, in addition to religious associations, it is also permeated with a kind of dignity and seriousness, so it is suitable for a ministry that is important from a national point of view. Fellner was commissioned by Minister László Lukács in 1899. The building was built between 1901 and 1904. In the archive photos, the steeples immediately draw the eye, on which the influence of the Maria am Gestade Catholic Church in Vienna is clear.

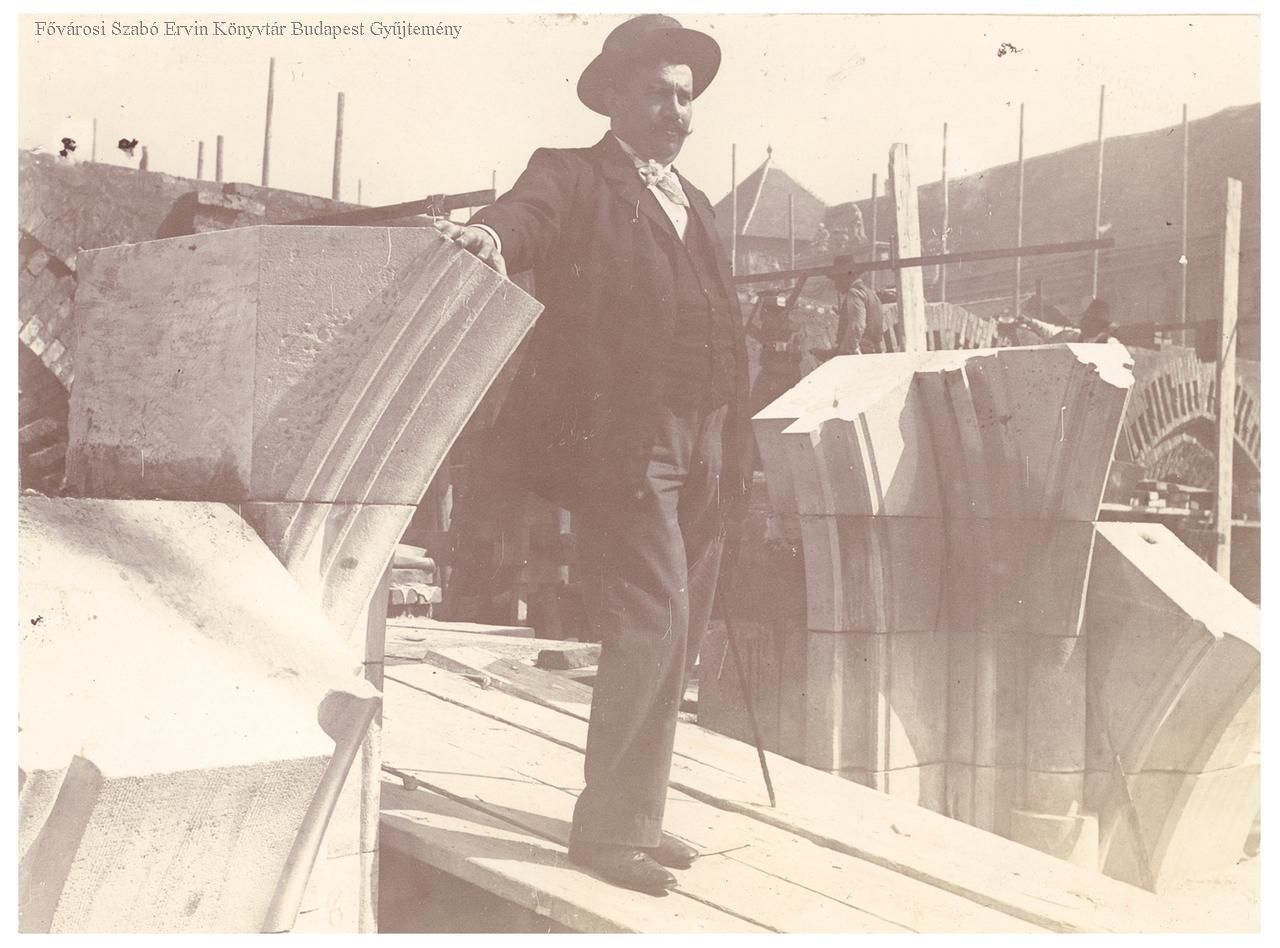

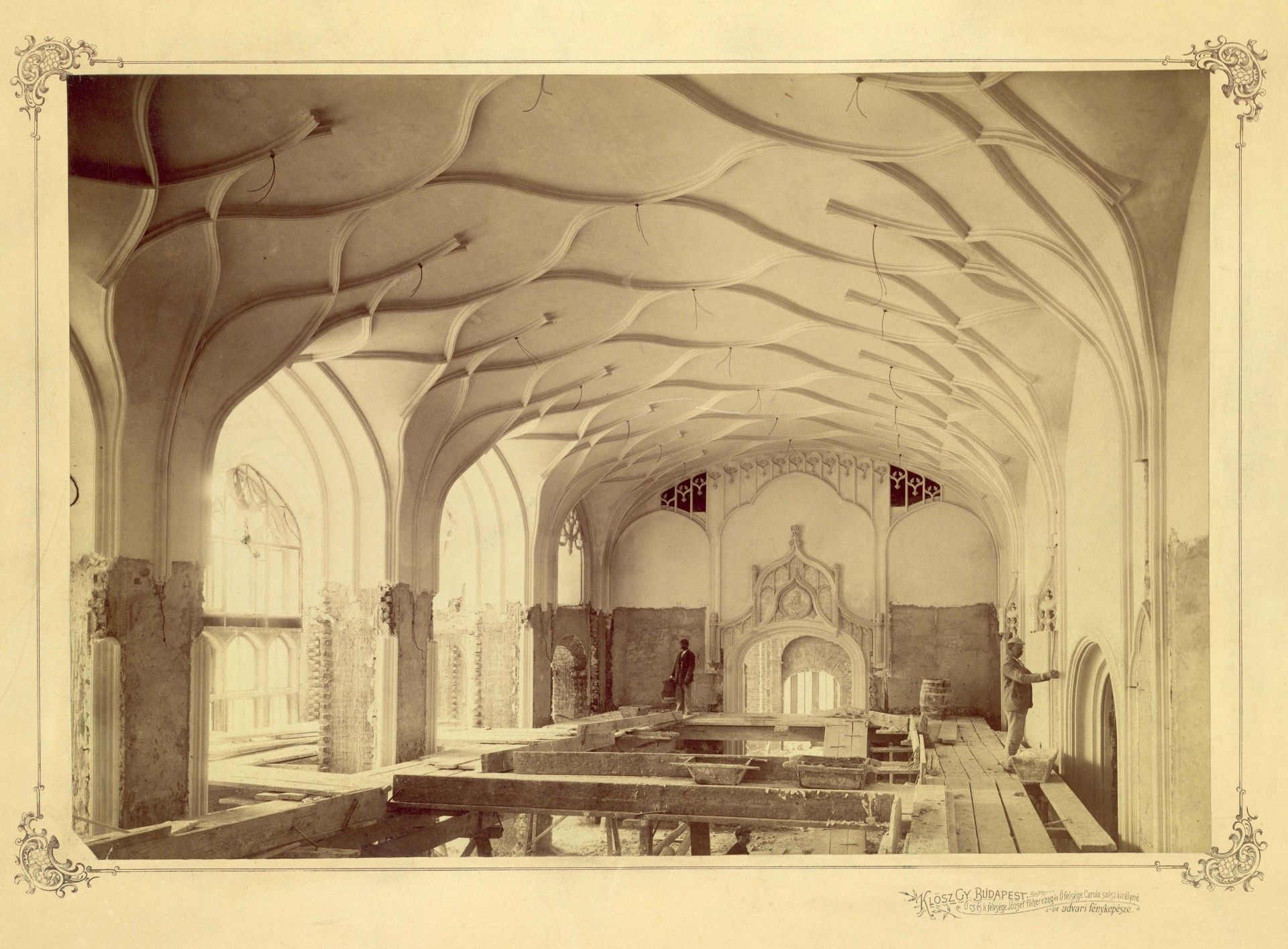

Sándor Fellner during the construction of the Ministry of Finance, around 1901-1904 (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Sándor Fellner during the construction of the Ministry of Finance, around 1901-1904 (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The Holy Trinity statue in 1934, behind it the Ministry of Finance (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 134534)

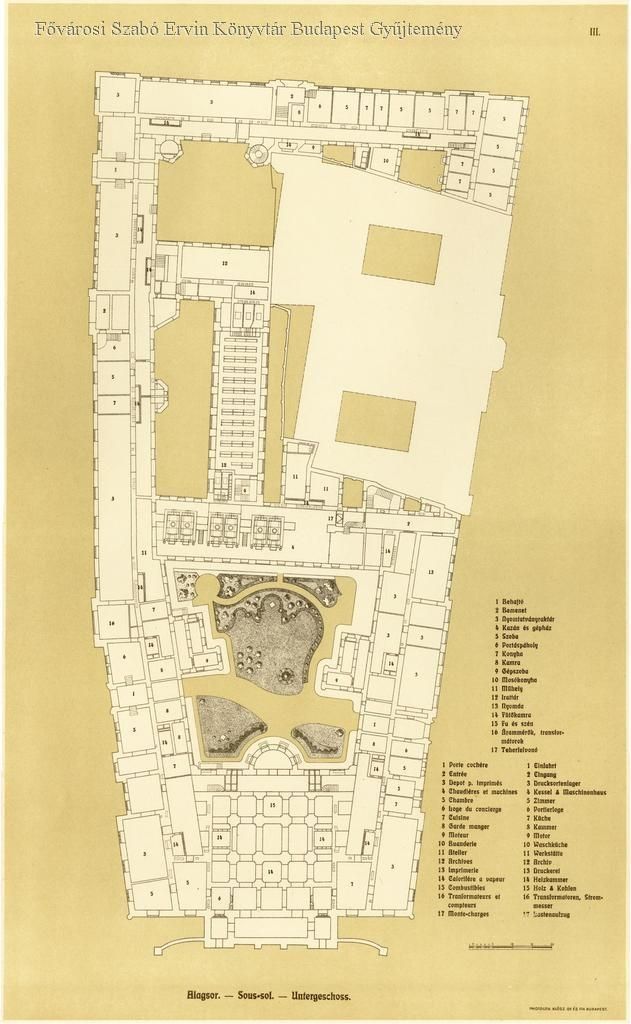

Ministry of Finance, ground floor plan, 1908 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Szentháromság Square, Holy Trinity statue, in the background the building of the Ministry of Finance in its post-World War II state, 1945 (Photo: Fortepan/Military Museum of Southern New England)

Szentháromság Square, Holy Trinity statue, in the background the building of the Ministry of Finance in its post-World War II state, 1945 (Photo: Fortepan/Military Museum of Southern New England)

However, taking a closer look at the building, elements borrowed from the Matthias Church can be found, which together with the roof covered with coloured ceramics, reinforce the similarity of the two buildings. The main façade seen in the old shots is made exciting not only by the airy carvings but also by the arched windows, the protruding, ornate middle Avant corps creating a particularly elegant effect.

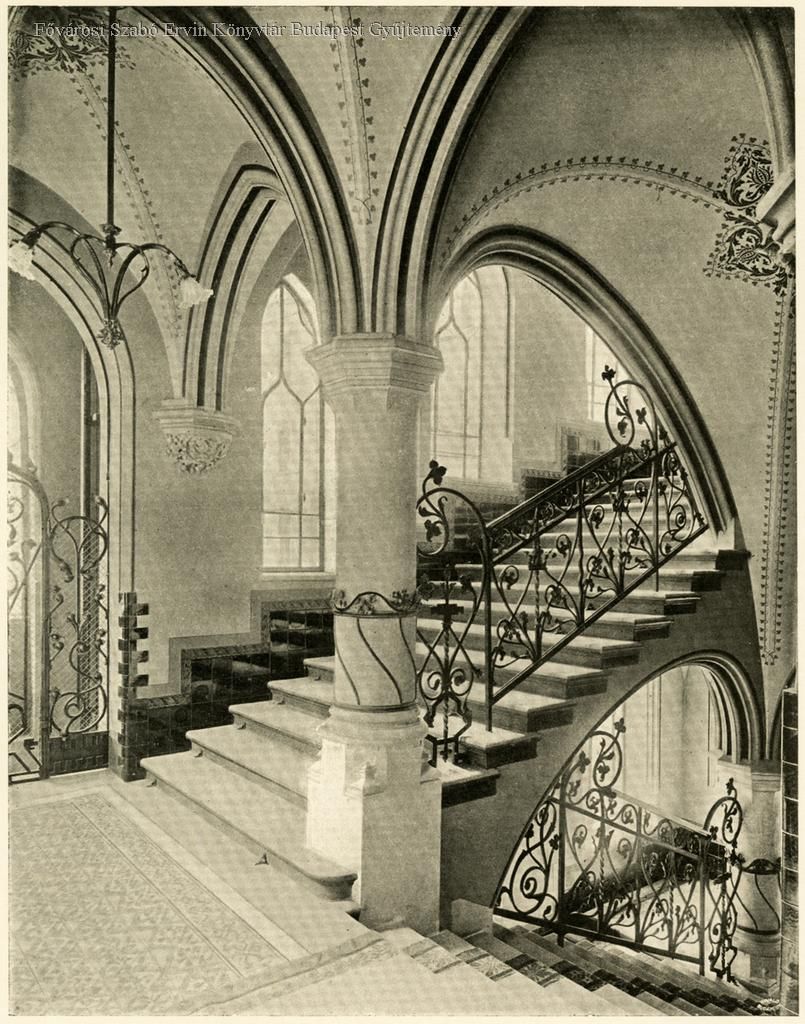

Inside, gothic spaces were created that harmonized with the facades, the most characteristic being the intricate vaults of the staircases and the representative halls. The building suffered significant damage during World War II. Although restoration would not have been impossible, unfortunately, the ruling party decided to simplify it.

Ministry of Finance, staircase, 1908 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Ministry of Finance, foyer, 1908 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Ministry of Finance, foyer, 1908 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Ministry of Finance, Szentháromság Square under construction, 1903 (Fortepan / Budapest Capital Archives HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.01.001)

Ministry of Finance, Szentháromság Square under construction, 1903 (Fortepan / Budapest Capital Archives HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.01.001)

Ministry of Finance, Szentháromság Square. Interior during construction in 1903 (Photo: Fortepan / Budapest Archives HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.01.004)

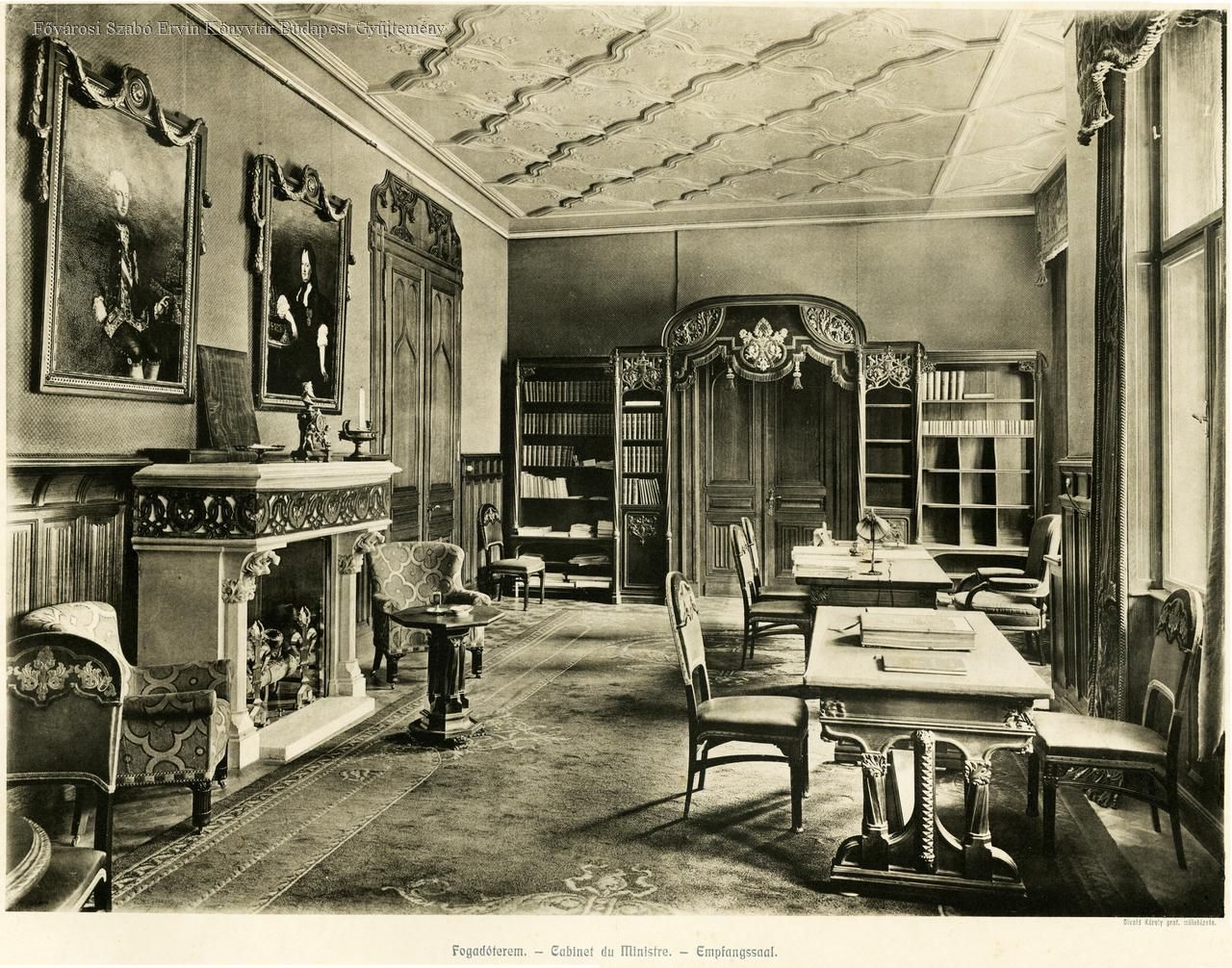

Ministry of Finance, reception hall, 1908 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The simple but tasteful reconstruction of the facade happened according to plans by Jenő Rados. The building functioned as a dormitory of the Budapest University of Technology for a long time, then it became the home of the House of Hungarians, but the National Archives also had several offices within. The Ministry of Finance wants to move back into the building, so it is currently undergoing reconstruction, with one of the main goals being the restoration of the original façade.

The Ministry of Finance will move into the building, so it is currently being rebuilt, the original facade is being reconstructed (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Another secular building with commanding authority is the Országház ('house of the nation'), commonly called the Parliament, which is probably the most famous building in Hungary. A book by József Rozsnyai and Zsolt Béla Szakács entitled The Short History of Hungarian Architecture offers insight into its creation.

The building stands on the banks of the Danube in Pest. Its monumental mass is reflected on the surface of the water, amplifying its effect. Although traditionally classified as a Neo-Gothic building, it could also be called a Gothic romantic, as a Baroque mass is covered in a Gothic robe. However, the time of construction clearly dates back to the era of historicism, so the neo-Gothic name remains.

The most famous building in Hungary, the Parliament on the banks of the Danube (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The most famous building in Hungary, the Parliament on the banks of the Danube (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The Parliament from Kossuth Square (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The Parliament from Kossuth Square (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

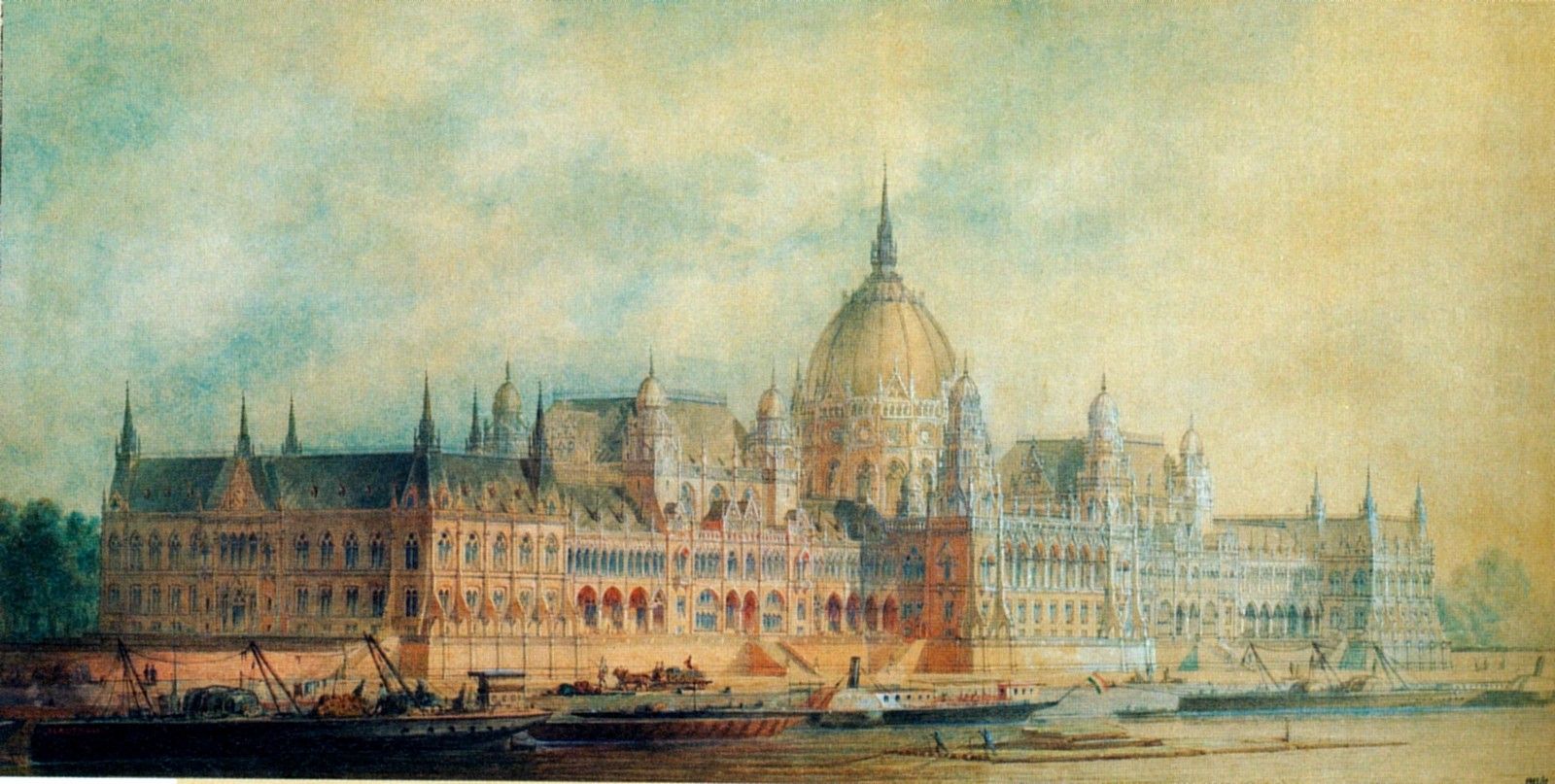

The building is the result of an international and open design competition, which was announced in 1882. Among the applicants, names such as Alajos Hauszmann, Albert Schikedanz and Vilmos Freund can be seen, but even the famous Viennese architect Otto Wagner drew up a design. The judges finally chose Imre Steindl's plan. Although construction began in 1885, due to the volume of the task and the difficult terrain, the Parliament was not fully completed until 1904. The main forerunner of the building is traditionally considered the Palace of Westminster, i.e. the Houses of Parliament in London Parliament, which is traditionally considered to be the work of Charles Barry, but new research shows that he may have collaborated closely with Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin.

Imre Steind's original design for the Parliament building (Source: Steindl album, 1923)

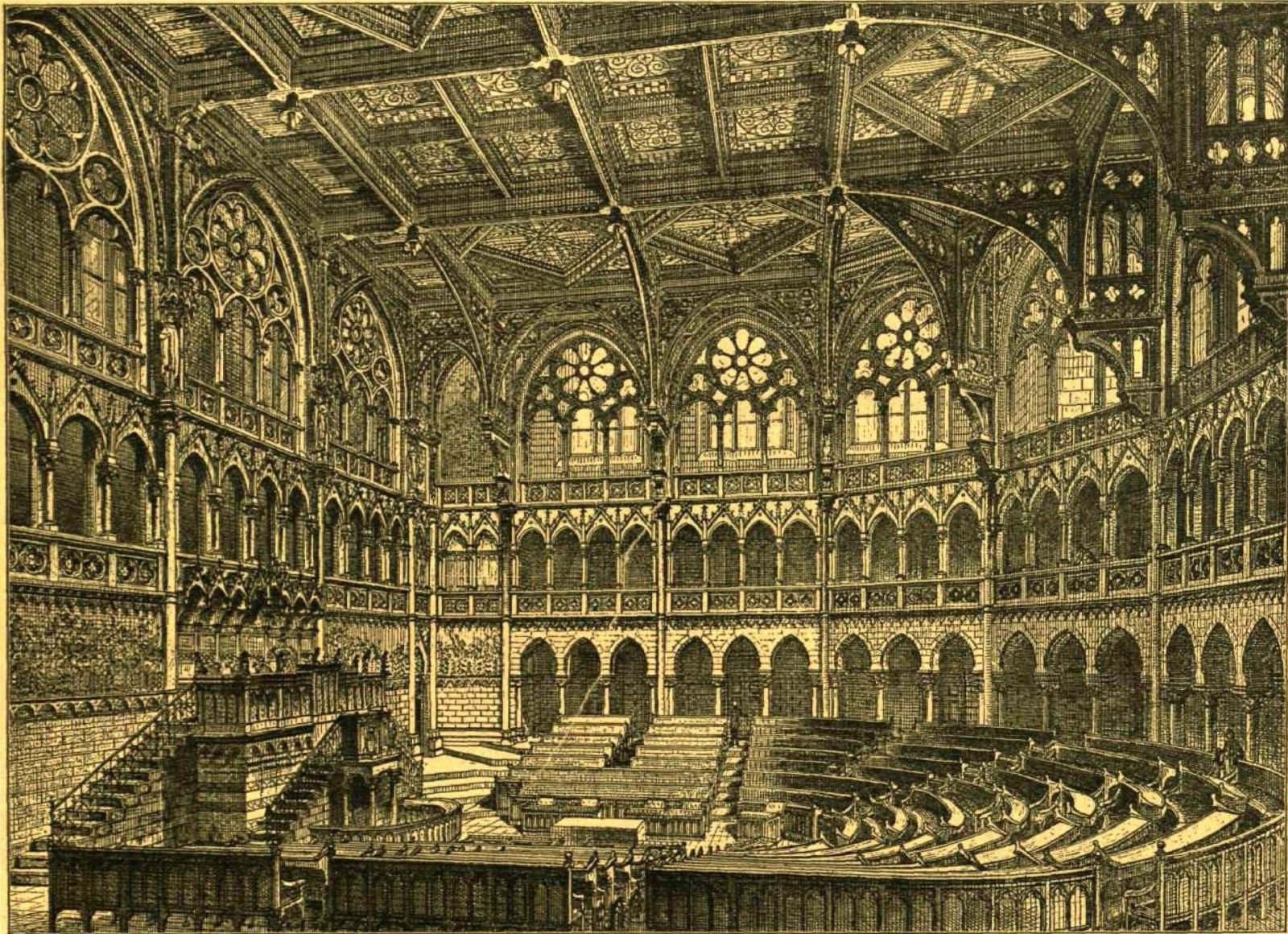

The mass of the horizontally spreading building is not Gothic in style, but its ornamentation is. Its location of the Thames is picturesque. The main entrance to both buildings opens on the side opposite the river and leads to a large-scale ornate staircase. From here, the sitting chambers in the two wings can be accessed, which are designed separately for the lower house and separately for the upper house. In London, these large rooms are rectangular, and in Budapest, they are horseshoe-shaped.

%20rakpartr%C3%B3l%20n%C3%A9zve.%20A%20felv%C3%A9tel%201896%20ut%C3%A1n%20k%C3%A9sz%C3%BClt.%20Fortepan%20BFL%20HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.08.109.jpg)

Parliament seen from Bem (Margaret) Embankment. Photographed after 1896 (Photo: Fortepan / Budapest Archives HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.08.109)

%20t%C3%A9r%2C%20t%C3%A1bori%20szentmise%20a%20Parlament%20el%C5%91tt%201915.%20m%C3%A1jus%2030-%C3%A1n.%20Fortepan.jpg) Kossuth Lajos (Parliament) Square, Mass in front of the Parliament on 30 May 1915 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 53601)

Kossuth Lajos (Parliament) Square, Mass in front of the Parliament on 30 May 1915 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 53601)

An important difference is that the most prominent elements of the British Parliament building are the tall towers at both ends, while in Hungary, a very impressive middle-domed layout dominates the building. The Parliament is not only decorated with meticulously crafted, Gothic carvings but also with more than two hundred statues inside and out.

%20t%C3%A9r%2C%20gr%C3%B3f%20Andr%C3%A1ssy%20Gyula%20szobra%20(Zala%20Gy%C3%B6rgy%2C%201906.)%20a%20Parlamentt%C5%91l%20d%C3%A9lre.%201907.%20Fortepan.jpg)

Kossuth Lajos (Parliament) Square, statue of Count Gyula Andrássy (György Zala, 1906) south of the Parliament in 1907 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 27692)

The interiors are made elegant not only by the gilding made using about 40 kilograms of gold but also by the ceiling paintings painted by Károly Lotz. The carpentry was completed by the famous Endre Thék, and the iron carvings on the towers were the work of Gyula Jungfer, an excellent blacksmith of the period.

Imre Steind's plan for the upper house chamber (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 27 May 1888)

Although Neo-Gothicism was given a smaller role in the architecture of historicism than the Neo-Renaissance style, it still enriched Hungary and Budapest with some masterpieces. The buildings described and many other excellent works have deservedly become the favourites of Hungarians and tourists alike.

Cover photo: Ministry of Finance, lobby, 1908 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)