The 19th century was a period of national rebirth in Europe. The countries of Europe turned to their glorious history during life-changing moments of traumas. The rapid industrialization of the century resulted in an increasing number of inventions.

In the second half of the century, world exhibitions or fairs were held regularly in Europe. In addition to highlighting industrial achievements, these global exhibitions also helped to create and present artworks. The first world's fair was held in London in 1851, and a monumental, basilica-like pavilion called the Crystal Palace was built to accommodate it.

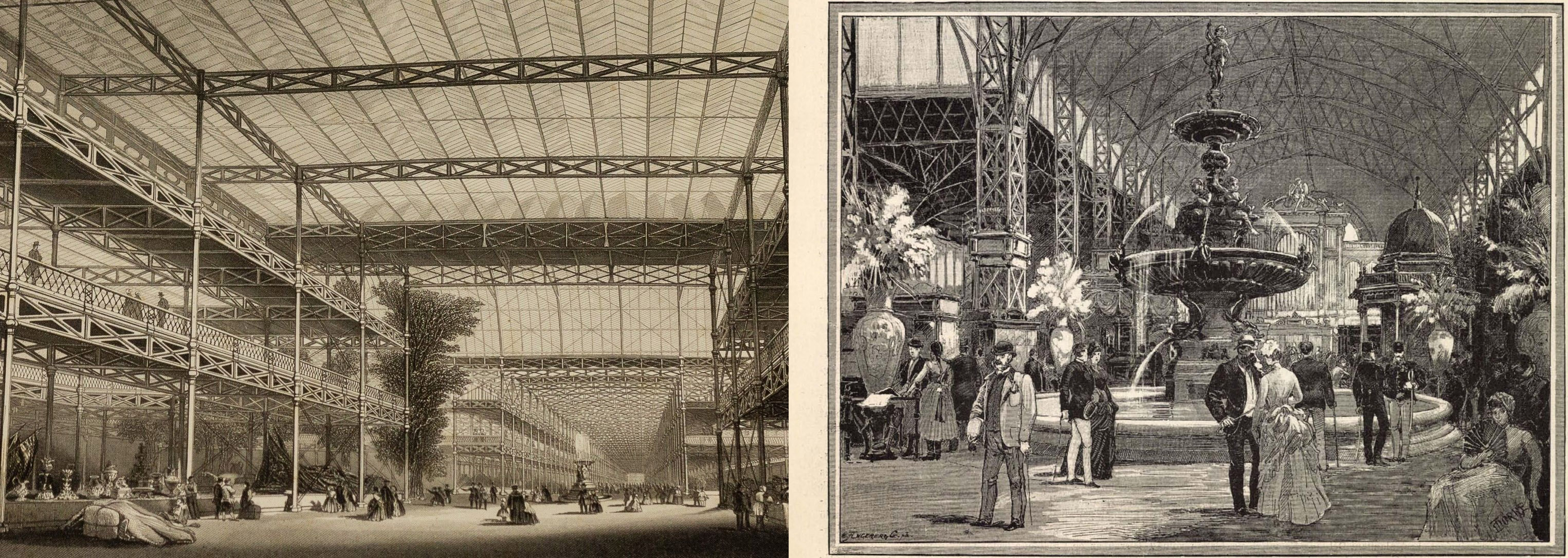

To the left is the Crystal Palace, the central building of the 1851 London World's Fair, to the right is the interior of the Budapest Iparcsarnok ('industrial hall') (Source: Private Collection/Vasárnapi Ujság, 26 July 1885)

At the Paris World's Fair in 1855, visitors were welcomed not only by a single large building but by the construction of independent, often representative pavilions for each nation. The first global exhibition to commemorate a historic anniversary of the host country was the 1876 Philadelphia World's Fair on the 100th anniversary of the independence of the United States of America.

The 1889 Paris World's Fair was also connected to a centenary celebration. Some of the buildings erected for world fairs were demolished as they were built of temporary materials, while others were given a new function. Some were rebuilt in other places. Others stayed in their original locations and became symbolic objects of a metropolis. The latter include the Eiffel Tower, built for the 1889 Paris World's Fair.

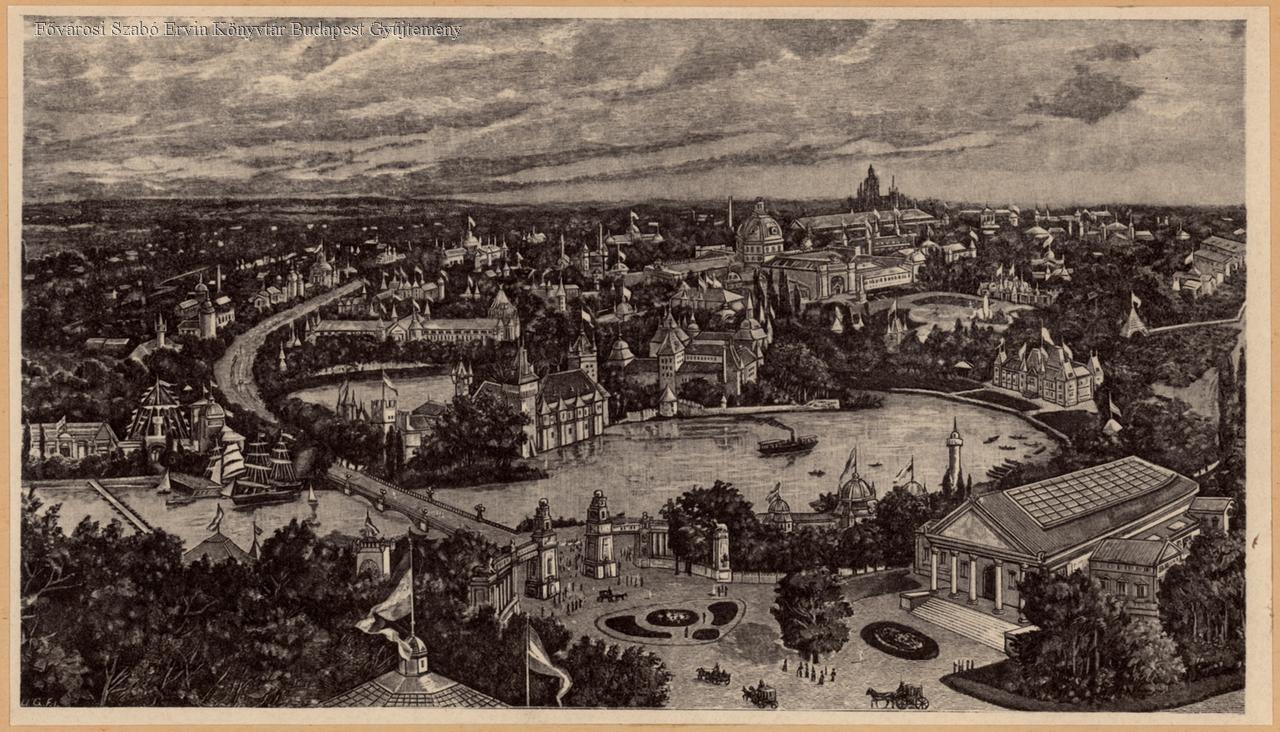

View of the National Millennium Exhibition in City Park on an 1896 graphic (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The 1896 National Millennium Exhibition in Budapest was not a world exhibition (although it was intended to be) but an exhibition covering the history of Hungary and its partner country, Croatia. Nevertheless, many similarities can be discovered between the world's fairs and the National Millennium Exhibition, including the fact that after the huge outdoor exhibition was closed, certain pavilions remained standing in Budapest or were rebuilt from more lasting materials.

The Applied Arts Exhibitions are considered the antecedent of the National Millennium Exhibition, which opened on 2 May 1896. They were organised by the Lajos Kossuth initiated Védegylet ('Defense Association') during the Reform Period of Hungarian History. They aimed to encourage the development of the Hungarian industry. In the middle of the century, the fairs were held in closed spaces.

View of the 1885 National Millennium Exhibition with the Iparcsarnok in the middle (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 17 May 1885)

The 1870s brought a change in the practice of organising exhibitions. The national exhibition of Székesfehérvár in 1879 was the first in the history of Hungary, where not only the products presented but also the pavilions themselves were part of the spectacle and testified that spectacular economic development began in the country after the 1867 Compromise.

Six years after that exhibition, in 1885, Budapest was a venue for a national exhibition in City Park. After the Compromise, this was the first time in Budapest that all branches of industry, trade and art had the opportunity to present themselves together. The “pavilions” of the exhibition in City Park were also architecturally significant.

Most of the buildings were built in a style showing Baroque and Renaissance forms of historicism. The most monumental building of the large-scale exhibition was the huge pavilion with a basilica layout called the Iparcsarnok. The Budapest Iparcsarnok, although on a much smaller scale, evoked the Crystal Palace of 1851 in its appearance and function. It was a solemn yet modern facility that served not just a single exhibitor but the entire industry.

The Iparcsarnok in 1896, recorded by György Klösz (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.10.005)

The National General Exhibition of 1885 can be considered the main rehearsal of the 1896 National Millennium Exhibition. Moreover, with the construction of the Iparcsarnok in City Park, the decision-makers of the Ministry of Commerce in 1885 designated the future location of the Millennium Exhibition.

The area was the “green heart” of Budapest, and because of rapid urbanization, its surroundings no longer represented the sparsely populated edge of the city by the early 1890s. It was a district where residential houses and bourgeois villas were built. Some of the pavilions in the 1885 exhibition also served as a venue for the 1896 National Millennium Exhibition. The Iparcsarnok was not demolished either, and it became one of the largest venues in the next major fair, the National Millennium Exhibition.

The interior of the Iparcsarnok during the National Millennium Exhibition in 1896 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

However, the need to celebrate the millennium anniversary of the Hungarian Conquest and the idea of an exhibition related to it had been floated much earlier, and this topic has been raised by many intellectuals since the 1850s. As the exact date of the conquest was not known, in 1882, the Ministry of Religion and Public Education asked the Hungarian Academy of Sciences to help determine a more accurate date. The scientific body, led by Arnold Ipolyi and Vilmos Fraknói, set up a special committee to provide a well-founded professional answer. However, professionals studying the era could not agree on a specific date, only the decade of the 890s.

According to their justification:

"...the abundance of data only reveals that before 888 Hungarians did not settle in the territory of today's Hungary, and in 900 the occupation of today's Hungary was completed, the Hungarian state was founded."

The organisation of the conquest's celebration was significantly influenced by the work of archaeologist and county bishop Arnold Ipolyi (1823–1886) and archaeologist and prebendary Flóris Rómer (1815-1889).

Arnold Ipolyi and Flóris Rómer played a significant role in preparing the celebration of the conquest

Flóris Rómer gave a lecture at the congress of the Hungarian Historical Society between 3-6 July 1885 in Budapest on "Creating a sense of history in the audience through festive processions, stage performances, national pictures, historical exhibitions and museums." According to Rómer, exhibitions, historical processions, theatrical performances, and historical education serve the same purpose: to develop a view of history for the different strata of society.

The deaths of the two Catholic priests in the second half of the 1880s did not slow preparations for the events, as many different members of the Hungarian intelligentsia were preoccupied with the idea of millennial celebrations. Count Jenő Zichy (1837–1906), a member of the Roman Catholic Church, suggested holding a world's fair, while Reformed Presbyter historian, Kálmán Thaly, a Member of Parliament, raised the idea of “seven national memorial columns”.

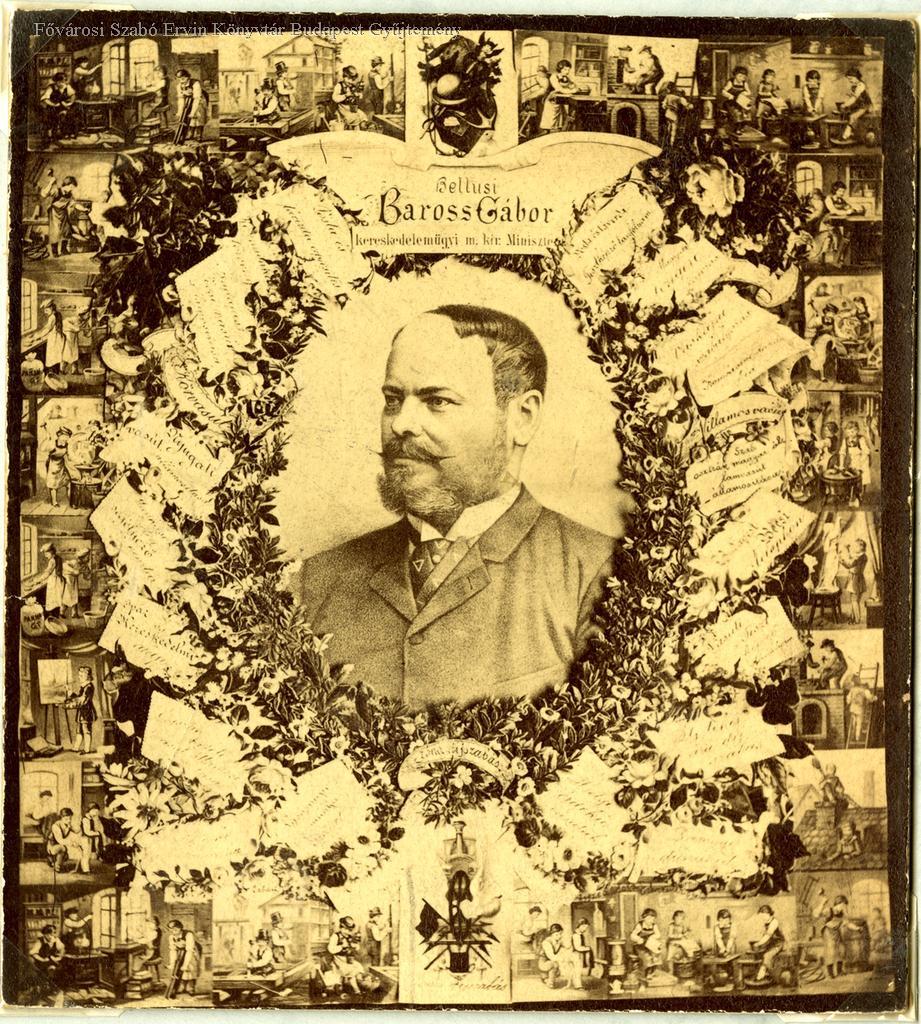

The National Millennium Exhibition Act was adopted in 1892 on the proposal of Gábor Baross (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

After the preparations of the 1880s, the early 1890s were marked by the practical preparation of the year of remembrance. Hungary recalled the last thousand years with unprecedented solemnity, which served to strengthen Hungarian national identity. Article 2 of the 1892 Act was passed based on the bill submitted to parliament by Gábor Baross (1848–1892) entitled "The National Exhibition to be held in Budapest, 1895".

Two years later, Baross decreed seven guard monuments to be erected at seven symbolic points in Hungary. The exhibition in City Park and the commemorative year were held in 1896 to ease construction.

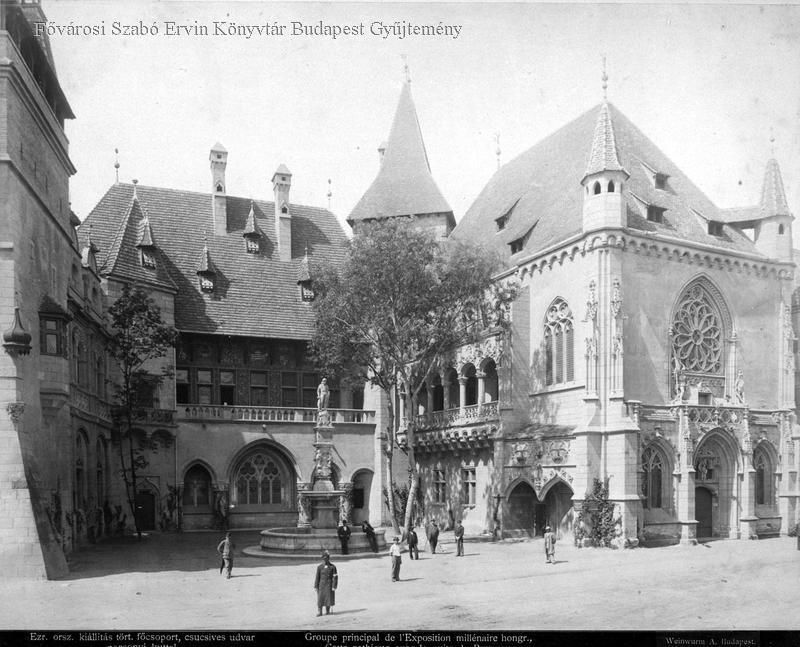

The National Millennium Exhibition, Historical Main Group, entrance gate in 1896 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

In the millennium year, the Hungarian Parliament passed Act 8 of 1896, entitled "On the works to be created to commemorate the millennium anniversary of the founding of the homeland". This legislation listed the tasks to be performed in the festive year and the plans for the coming decades, including the equestrian statue of King St. Stephen in Buda Castle and the Museum of Fine Arts.

The Royal Pavilion, which was already a Gerbaud confectionery by 1896 (Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.10.004)

The most popular weekly of the era, the Vasárnapi Ujság praised the millennial anniversary of the conquest in May 1896:

“Hungary is celebrating a great event: the millennial anniversary of its existence, of the Hungarian nation's settlement in its homeland. Hearts open wide and are filled to the brim with feelings of joy and pride. We have enough reasons for joy that the good Lord has allowed us to live through this year, and to be proud that we withstood so many dangers, thunderstorms intact, unbroken. What a thousand years are behind us!”

For the residents of Hungary, a visit to the National Millennium Exhibition in City Park and the fact that a series of new public buildings were built on the anniversary of the conquest (in Budapest, among others, the Comedy Theater, the Kunsthalle, the Museum of Applied Arts, the Royal Hungarian Curia, and the Ferenc József Bridge) gave the experience that they are citizens of a nation with a rich past and a bright future ahead.

The Kunsthalle of 1885 in 1896. Later it became the Olof Palme House, then the House of Hungarian Artists, from 2019 the House of the Hungarian Millennium (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 31748)

This National Millennium Exhibition was both a spectacular venue for presenting historical monuments and a dazzling entertainment venue.

The building of the Historical Main Group of the exhibition was designed by architect Ignác Alpár (1855–1928). He shaped the architectural presentation of the millennial past with parts of the building representing characteristic styles. With his work, the architect met the expectation expressed by the organisers: "It is desirable that the motifs of Hungarian history or old Hungarian buildings be used". In the building complex designed by Alpár, the Castle of Vajdahunyad in southern Transylvania, a detail of the “ancient nest” of the Hunyadi family, appeared with special emphasis, recalling the greatness of the "Turk beater" János Hunyadi and his son, Mátyás Hunyadi.

The arched courtyard of the National Millennium Exhibition's Historical Main Group with the Pozsonyi Well, 1896 (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

After the millennium celebrations, a significant part of the temporary buildings of the 1896 exhibition was demolished, but the Iparcsarnok remained the most important exhibition place in the capital in the first half of the 20th century. The Iparcsarnok suffered significant damage during World War II, so it was demolished after 1945.

The building of the Historical Main Group of the exhibition was rebuilt from more lasting materials ten years after the fair's closing. Among the details of the castles and town halls built hundreds of kilometres apart in different eras, the unit evoking the Castle of Vajdahunyad in southern Transylvania is the most evocative. In connection with the Neo-Gothic part, which evokes the glorious age of the Hunyadi family, the entire building complex is often mentioned by the residents of the capital as Vajdahunyad Castle.

Entrance to the Vajdahunyad Castle today (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The exhibition of 1896 brought a less well-known part of Budapest to the fore, both through its historical significance and its effect on real estate value.

Cover photo: The Main Historical Group of the National Millennium Exhibition, Vajdahunyad Castle at the 1896 exhibition, photographed by György Klösz (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.01.002)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration