Although the battlefield of World War I was far from Budapest and the capital was not directly affected by the fights, the years-long war had already exhausted the home front by 1916. Mainly those families were in a difficult situation, where the husband was a soldier, while the wife – possibly with several children – was left alone. The state tried to help them with food kitchens that delivered cheap lunch to their doors. A bowl of vegetable dish or other simple foods meant life to many.

Népszálló was built in 1912 as a workers' hostel on Aréna (today's Dózsa György) Road. In its kitchen, food was cooked in 1916 that the food kitchen's cars delivered to families in need. Photo from 1913 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The Public Welfare Department (Népélelmező Osztály) of the Budapest Central Assistance Committee launched the food kitchens (called mozgókonyha, or moving kitchen in Hungarian). The name is misleading because the food was not cooked in the cars, but in the kitchen of the Népszálló, the vehicles just delivered the food. The first two cars set off on 11 May 1916, 105 years ago, to the poorer quarters of the capital. The cheap but nutritious food was taken to families who, for some reason, e.g. the mother was ill or did military work, could not get to the soup kitchens or cook for themselves. Népszava reported on food kitchens in the 10 May 1916 issue:

"The food is prepared in the kitchen of Népszálló in the 6th District and is distributed in hygienic, well-sealed pots in the poorer parts of the city. For the time being, the Public Welfare Department of the Assistance Committee is organising test runs, in which members of the Public Welfare Department will also take part. Tomorrow, on Thursday, two cars will depart. One of them will be in the 7th District's Grassalkovich Street from 11:30 a.m. The other will begin lunch service at the same time in Szvetenay, Gyep, Márton and Gát Streets. A half-litre of vegetable dish or pasta will cost 20 fillér."

Help was also needed because there was significant inflation during the war, so the cost of living also rose. At the outbreak of the war in 1914, the price of potatoes, for example, quadrupled in a few weeks. In 1914, 20 crowns a week was enough to provide a minimum provision for a family of five, and two years later, 64 crowns were (would have been) needed. It is true that wages also increased to some extent, but they could not compete with food prices. In addition, the most important groceries had been given in exchange for food tickets.

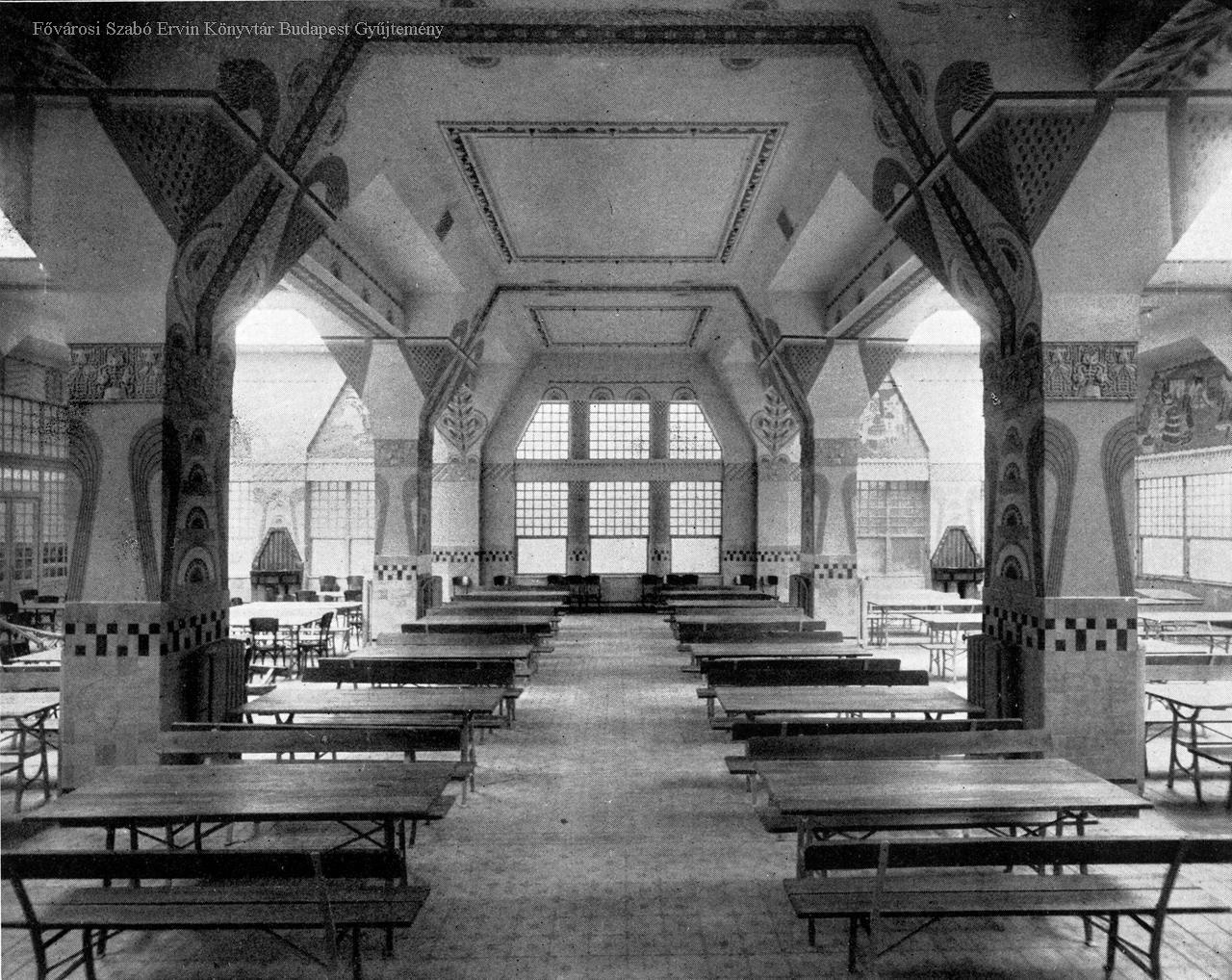

The dining room of the Népszálló, in peace time conditions in 1913 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The welfare organisation that initiated the food kitchen, the Budapest Central Assistance Committee, not only did charity work but also took an active part in maintaining the fighting morale, organising lectures on the topic. Its president was Mrs Leó Lánczy, who was the wife of the Hungarian Commercial Bank of Pest's president. The organisation recognised that in addition to the encouraging presentations, the poorer need to be helped in other ways, such as with cheap meals. Accordingly, in the food kitchens, the weekday menu was 20 fillér, and on Sunday, goulash cooked from horse meat was offered for 40 fillér.

According to contemporary press reports, the first cars were besieged by such large crowds that new vehicles had to be launched within days. Népszálló's kitchen had reached the limits of its capacity by June, so a temporary kitchen was built next to the hostel for 8,000 crowns, in which another 800-1000 servings of food could be cooked.

Népszálló was originally built as a workers' hostel in 1912 according to the plans of Lajos Schodits and Béla Eberling, at 152 Aréna, now Dózsa György Road. It was a military hospital in World War I, but the poor could also eat in its kitchen. It provided food for 1,000 people a day. The menu was more expensive here than in the food kitchens. The price of meatless lunches was 40 fillér until the summer of 1916; after that, it was 60, and the price of lunches with meat was also raised in 1916 to 1 crown and 70 fillér. The latter was hardly needed; according to the June 1916 report of the Budapest Central Assistance Committee, only four servings a day were sold on average.

People in line at the Rákóczi Square market in 1918. Food prices skyrocketed during the war (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The food kitchens had another task in September 1916 as thousands of refugees from the Romanian invasion of Transylvania had to be provisioned. They were already cooking food for 3,000 people at Népszálló by this time. On 10 September 1916, the Ujság described the kitchen:

"The kitchen building itself is not large. It is an L-shaped building. There are eleven cauldrons on the longer side which have to be reached by stairs. The largest has a capacity of nine hundred litres, but even the smallest one can hold three hundred litres of food. Five thousand litres of food can be cooked at a time in the eleven cauldrons, which means that ten thousand people can be fed from here."

In addition to supplying refugees, a total of 1,500 servings of food were distributed daily to poorer people in two omnibuses and two 'goulash cannons' (gulyáságyú, mobile equipment used in the food kitchens). The cited article also reported the menu:

"From Thursday of this week until Wednesday of next week, this is the daily menu of the food kitchen: cabbage cubes, cabbage vegetable dish, a dish of vegetable marrow, poppy seed noodles, baked beans, pasta with semolina, kale. There is only one type of food every day, and all four places offer that one dish."

The war was nowhere near its end, as it only ended in the autumn of 1918. By then, the country was completely bled out, which hit those in poverty much harder than the rich.

Cover photo: Queues in Teleki Square in 1918 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration