A decree of Joseph II regulated the construction of “public lighting” in Pest in 1789: the oil lamps had to be installed every 20 fathoms, and the costs of the installation had to be covered by the sale of houses beyond the Vác gate. Lighting and wine taxes were levied on operating costs. Setting up a lantern was not cheap at the time. It cost 7 forints and 40 pennies. In addition, its operation required constant monitoring, as the oil and wick had to be replaced, and each lamp had to be lit separately and then extinguished.

Gaslamp in the city centre at the end of the 19th century, photographed by György Klösz. (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.06.054)

In the 18th century, in addition to oil, a new material appeared that could be used for lighting: "air spirit", i.e., city gas (illuminating gas). This was not the same as natural gas used for cooking and heating today, but a combustible gas typically produced from coal. Brave experimenters used city gas to illuminate halls, factories, or even homes and soon after appeared in street lamps, first in 1807 in London.

István Széchenyi could have been the Hungarian pioneer of street gas lighting, as the Hungarian count did not return home empty-handed from his trip to England in 1815. He smuggled out a model of a gas generator and even learned how to operate the device to illuminate his castle in Nagycenk. Smuggling was to be taken literally here, as the export of such machines was prohibited under English law at the time. Had Széchenyi been caught, he could have been sentenced to death.

A wall gas lamp in the Egyetem Square at the end of the 19th century, photographed by György Klösz (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

In the meantime, there was someone in Pest who made a gas generator. Namely, Lajos Tehel a doctor living in Óbuda. Tehel, who had a wide range of interests, was involved in many things: he climbed the peaks of the Tatras for scientific purposes, donated medals from the Roman era to the National Museum, where he was also the guardian of the mineral collection from 1810.

This researching doctor developed gas in 1816, with the help of which on 5 June 1816, the first street gas lamp in Pest lit up. Exactly on the facade of the National Museum building at that time, which was in the Egyetem Square, since the museum was still housed in the old university building. The new lighting device was a great success, many people watched it in the next few days, and on 20 June, it was even seen by Palatine Joseph and his wife.

The first issue of the Tudományos Gyűjtemény in 1817 wrote about Tehel's experiment:

„In the city of Pest, Dr Lajos Tehel, a worthy member of the National Museum, attempted to illuminate the roads at night by transformed air (gas); with great luck.”

Unfortunately, the pioneering experiment that Tehel also presented to the general public as a path to future development did not continue immediately. One of the reasons for this may have been the death of the creator, Lajos Tehel, in November 1816.

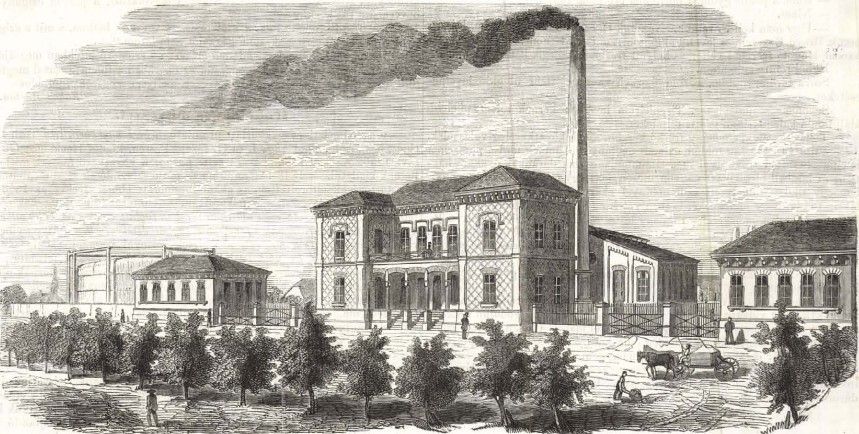

The building of the Pest gas lighting, i.e., the City Gas Factory (Légyszeszgyár) on a contemporary drawing (Source: Vasárnapi Újság, 1856.)

However, the ghost had already come out of the bottle. In more and more places in Pest, gas flames were ignited on private initiatives. In 1827, banker Frigyes Kappel lit his house on Bálvány Street and the section in front of him with gas 6 October. Other wealthier citizens followed this practice.

Former gas lamp of the Chain Bridge (Photo: The Transformations of the Chain Bridge exhibition, The Hungarian Museum of Science, Technology and Transport, Ábrahám Ganz Collection)

However, not everyone was thrilled with the new lighting. At the Magyar Theatre in Pest, for example, where it was used from 1838, contemporary audiences believed it was smelly rather than bright. Mór Jókai put it this way: "this gas had a musty smell".

There have also been initiatives to introduce gas lighting in public areas. The plans were presented to the aldermen in Pest in 1844, but they did not support them yet. It was calculated that the planned street gas lighting would have cost triple as much as maintaining the existing oil lamp system. And expensive operation deterred the aldermen, even though there was a great demand for better public lighting. On the news of the try-out, the Nemzeti Ujság wrote on 10 September 1844:

“We hear that the city of Pest intends to use city gas lighting, and the glorious streets in which death or at least a leg fracture grins from the pits to the pious passenger are chosen for testing. We can only enjoy this because in some places, around 8 o'clock in the evening, the lights without oil are dying so sadly, as if we are mourning our national joy.”

Demonstration of various wrought-iron gas lamps in the yard of a house in the 1890s (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The "large-scale" street gas lighting had to wait until 1856 in Pest. The Trieste General Austrian Gas Company received the exclusive right to set up a gas factory and gas lamps on the streets of Pest in 1850. The gas factory was built in 1855 on the then Lóvásár, today's Pope John Paul II Square. Its memory is preserved on Légszesz and Gázláng Streets next to the square. The first gas lamps set up for public lighting lit up on Kerepesi (today's Rákóczi) Road at the end of 1856. A total of 838 lamps were installed in public areas.

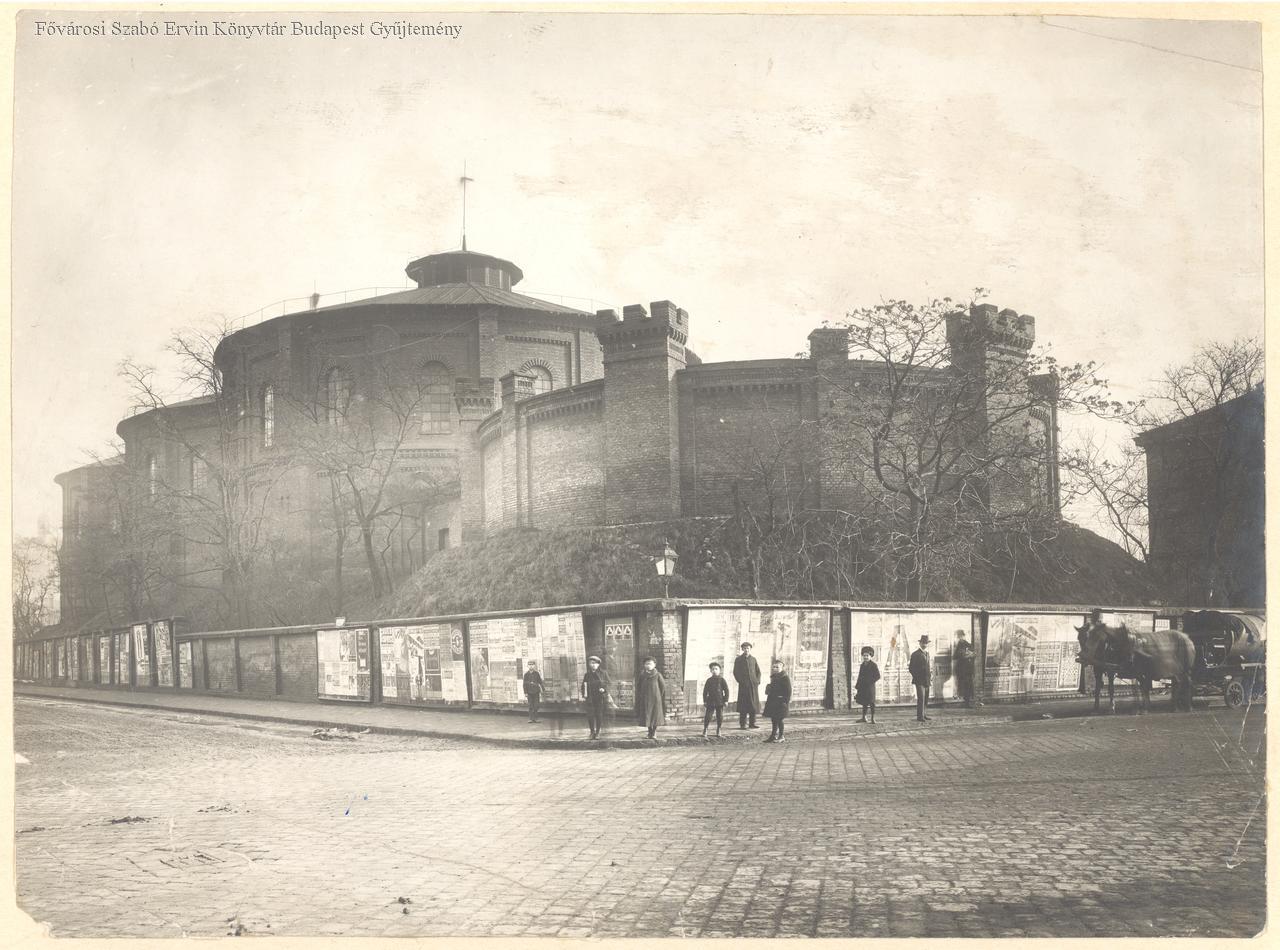

The City Gas Factory at the intersection of Köztemető Road and Légszesz Street around 1900 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

From then on, the network expanded, with gas lighting built on the Chain Bridge in 1859. Until then, the bridge had been illuminated with oil lamps, with little success. However, the system built in the 1850s was more economical than oil lighting. A good example of this is the Chain Bridge, as the Chain Bridge Company shows that the oil lighting cost 2246 forints and the gas only 1615 forints a year.

Today's successors of ornate gas lamps in the Buda Castle (Photo: Balázs Both/PestBuda.hu)

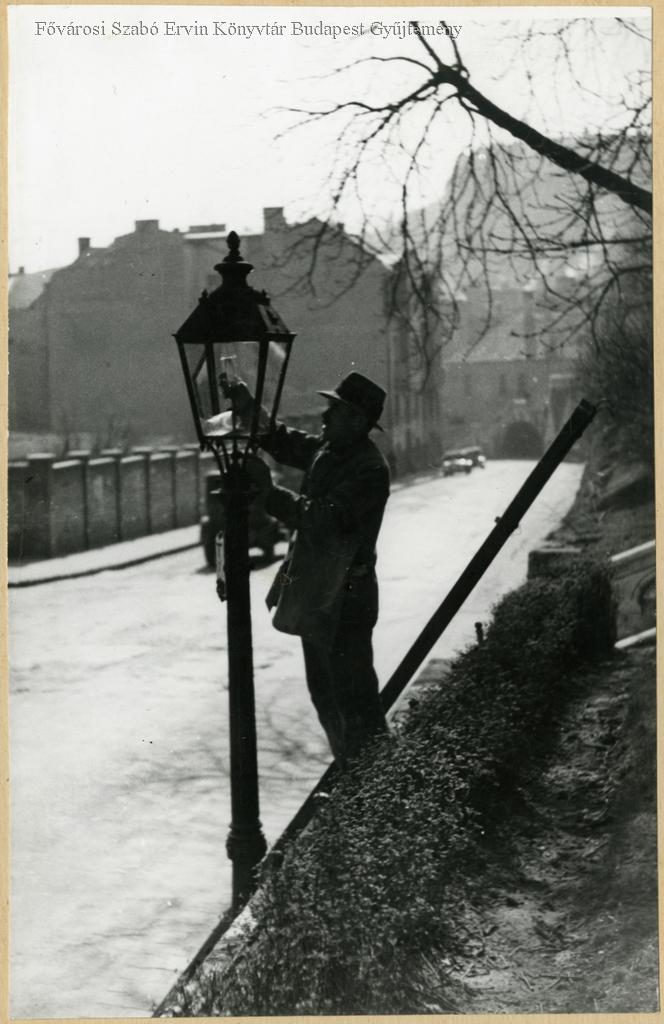

The pipes were led to Buda (on the Chain Bridge) in 1862, and by the time, the gas lamps could already be lit here. The lighting devices were supplied with gas through the pipes of the central gas factory, but the flame had to be ignited locally. The lamplighters did this work. They diligently walked the evening streets and, with the help of their long sticks, revived the flames in each lamp, of which there were quite a few since when the city was united in 1873, 1669 lamps in Pest and 501 lamps in Buda were lit in the streets.

Electric lighting stopped the spread of gas light, but in 1930 there were still 16,000 gas lamps in Budapest, and 141 lamplighters started in the evenings to light them. (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Cover photo: Lamplighter in Hunyadi János Street in 1936 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration