In the second half of the 19th century, the most dreaded disease was cholera, one of the major waves of infection of which swept through Pest and Buda in 1872-1873, claiming many casualties. In addition to cholera, there were other regular epidemics: typhoid, tuberculosis, diphtheria, scarlet fever - then called "vörheny - or smallpox (which has now completely disappeared).

That is why the authorities have taken measures to prevent the spread of epidemics. For defense and preparation, modern epidemic and public hospitals were built, sewerage was constructed in the city, and regulations were changed.

The former St. John's Hospital stood in what is now Széna Square. Primarily infectious patients were cared for here, but its design was no longer adequate (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The former St. John's Hospital stood in what is now Széna Square. Primarily infectious patients were cared for here, but its design was no longer adequate (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Although cholera subsided after 1873, several other epidemics appeared from time to time. According to records, in April 1881, most died of pneumonia, 52 of smallpox, 19 of typhus, five of scarlet fever, and eight of measles. The diphtheria wreaked havoc with its 25 victims. On 23 April 1881, the paper Hon published a compilation of the state of public health in the capital. In this we can read the following:

“The state of public health in the capital in the March snow was also unfavorable, according to a report by the chief medical officer, because both morbidity and mortality increased - however, mortality was lower than in the similar month of the previous two years. Respiratory ailments, especially pneumonia, were predominant in this snow as well; - ailments from gastrointestinal disorders were reduced. In the 2nd, 3rd and 5th Districts, malaria [then called váltóláz] was more frequent. Among the acute infectious diseases, smallpox, typhus and diphtheria increased, - scarlat fever and and measles decreased. (…) ”

The dreaded smallpox - against which there was already a vaccine - struck Soroksár in early 1881, and a hundred patients were identified. To stop the spread, teaching was suspended in all schools in Soroksár and dance parties were banned. Despite all this, smallpox was widespread, though it no longer wreaked havoc. On 21 April, the Ellenőr wrote:

“The smallpox epidemic is already on the verge in the capital. From the barracks hospital, where a separate ward for smallpox patients was set up, once the number of smallpox patients began to decline, 2-3 recovered individuals has been discharged daily. Some cases still occur - but less frequently. ”

In the same year, a disease called "hagymáz" at the time, typhus, also appeared in Budapest. The Hon wrote about the epidemic on 29 May 1881:

“The typhus epidemic. Because the typhus cases are taking on larger scales day by day, the mayor, following the 157th article of Act 16 of 1876, convened an extraordinary meeting of the Public Health Committee to discuss the question of whether this would be the date for the establishment of the epidemiological committees."

The disease was most prevalent among the poorest, with the brick factory of Rákos named as its centre. The epidemic was kept under control, with officials in the capital reporting to newspapers stressing that the news of the epidemic was greater than the actual spread of the disease, with the number of cases not rising above 40 a day. In the affected 10th District, or as a precaution, in the adjacent 8th and 9th districts epidemiological committees have been set up.

The center of the typhus epidemic of 1881 was the brick factory in the 10th district. The picture of the Drasche brick factory was taken later, in 1933 (Source: FSZEK, Budapest Collection)

The center of the typhus epidemic of 1881 was the brick factory in the 10th district. The picture of the Drasche brick factory was taken later, in 1933 (Source: FSZEK, Budapest Collection)

In order to control the epidemics, the Budapest authorities introduced new rules with effect from 1 July 1881. Outbreaks must be reported throughout the capital so that authorities are informed in good time of the latest cases. They also prescribed quarantine of patients and banned sick children from attending school. The rules included the need to disinfect the home in case of many diseases, such as cholera, typhoid, smallpox, or diphtheria.

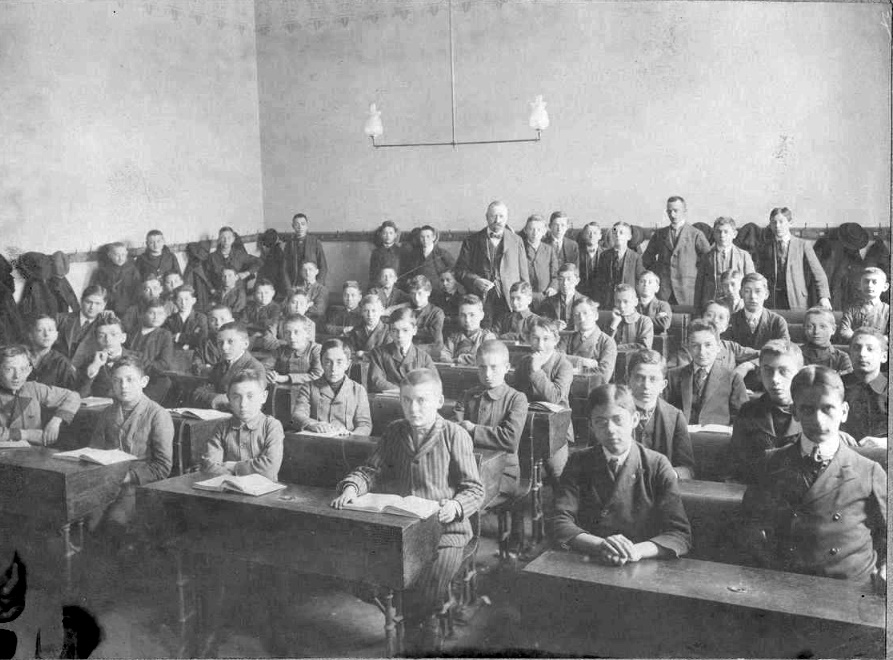

A classroom of a contemporary school, the Markó Street grammar school. In case of an epidemic, the affected schools had to be closed (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

A classroom of a contemporary school, the Markó Street grammar school. In case of an epidemic, the affected schools had to be closed (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Of course, the epidemics did not go away. However, as sewerage spread, as public health developed slowly, no devastating epidemic developed from local diseases. The fight against traditional infectious diseases continued with the establishment of public baths, disinfection stations, the spread of sanitation and the development of hygiene practices.

The Budapest Disinfection Institute on Váci Road, the institution was built in 1912-13 (Source: Hungarian National Museum - Semmelweis Museum of Medical History)

The Budapest Disinfection Institute on Váci Road, the institution was built in 1912-13 (Source: Hungarian National Museum - Semmelweis Museum of Medical History)

Although some diseases will disappear or become harmless, but as we have seen in the last year and a half, other diseases may appear in their place, and then we will go back to the old well-established rules, as we did (and do) in the current epidemic. The recipe was ready, we just had to apply it.

Cover photo: The St. Ladislaus Hospital in the was built as an epidemic hospital at the end of the 19th century (Source: Fortepan / No.: 82459, Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.07.135)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration