Budapest is also known to the world as a great spa town; its reputation is due to its many baths and medicinal waters. In the Hungarian capital, there is a long history of bathing culture, in which some baths have been “protagonists” for several centuries, while others have been “episode actors” operating only for a few years or decades.

The Dunafürdő [Danube Bath]

After the Salt Office was demolished in 1820 in Pest, in the Kirakodó Square (today Széchenyi Square), several plots were established in its place. One of these - today's 3 Széchenyi Square - was bought by Ignác Pfeffer and his wife in 1821. As early as 1822, they received a building permit, so the Pfeffer couple began to build their baths, designed by József Hild, who was also the construction manager.

The Danube Bath was opened in 1823. In the part of the building overlooking the Kirakodó (now Széchenyi) Square, flats were set up, while in the back and in the wing facing the street, the bath itself was built. Due to this, from 1823 until 1925, this street was called Fürdő [Bath] Street. At that time, the Budapest Public Works Council renamed it gróf Tisza István Street in honor of the late Prime Minister. After the Second World War, it became József Attila Street.

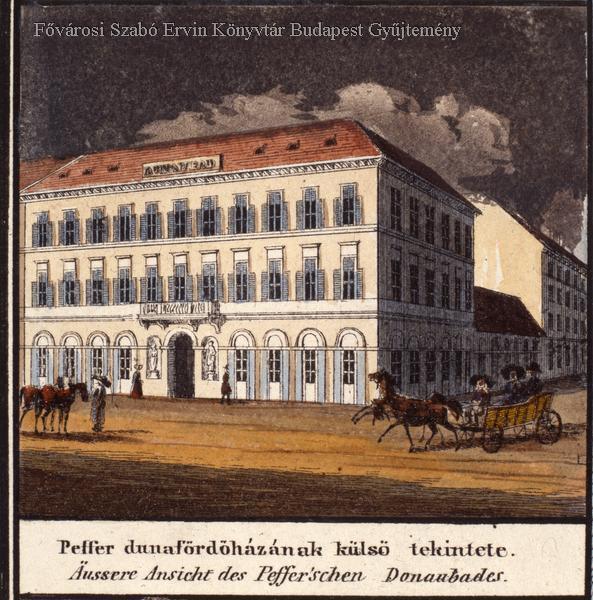

In the part of Pfeffer's Danube Bath - later called Diana Bath - overlooking the Kirakodó Square (now Széchenyi) Square, flats were designed, which can be clearly seen in this picture taken in 1837 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The Danube Bath started its operation as a so-called tub bath. This meant that the water of the Danube was lifted out with the help of a mechanism and led to the bath, where it was heated in winter and let into the bathtubs.

Since 1833, the Danube Bath was referred to as the Diana Bath by the contemporary press. We do not know the exact reason for the name change: they may have started to call the place after the statue of Diana in the bath, or they may have followed the Viennese fashion, where there was already a Diana Bath.

The Diana Bath in 1837 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The great flood of 1838 did not cause significant damage to the building, but it burned down in May 1849. Namely, when the troops of Artúr Görgei wanted to take over the Buda Castle that was in imperial hands, Hentzi started shooting Pest. The spa also received several hits, resulting in a fire. It was not until 1850 that Ignác Pfeffer renovated the building. Four years later, Ignác Pfeffer Jr. took over the bath and expanded it: on the second level he set up a steam bath.

This is partly due to the fact that the Diana Bath became very popular and provided a significant income for the Pfeffer family. Interestingly, the decline of the bath was caused by the unification of Pest, Buda and Óbuda. After 1873, the people of Pest moved to the more renowned baths in Buda, where there was medicinal water. The Pfeffer family soon sold the once famous bath to the Hungarian Commercial Bank of Pest, which demolished it. Their new headquarters was built in its place, which still stands to this day.

The Margit fürdő [Margaret Bath]

Archduke Joseph Karl, son of palatine Joseph, commissioned mining engineer Vilmos Zsigmondy to explore the thermal water springs on Margaret Island in 1866, as thermal springs on the former so-called Fürdősziget on the northern shore were found as early as the 1850s.

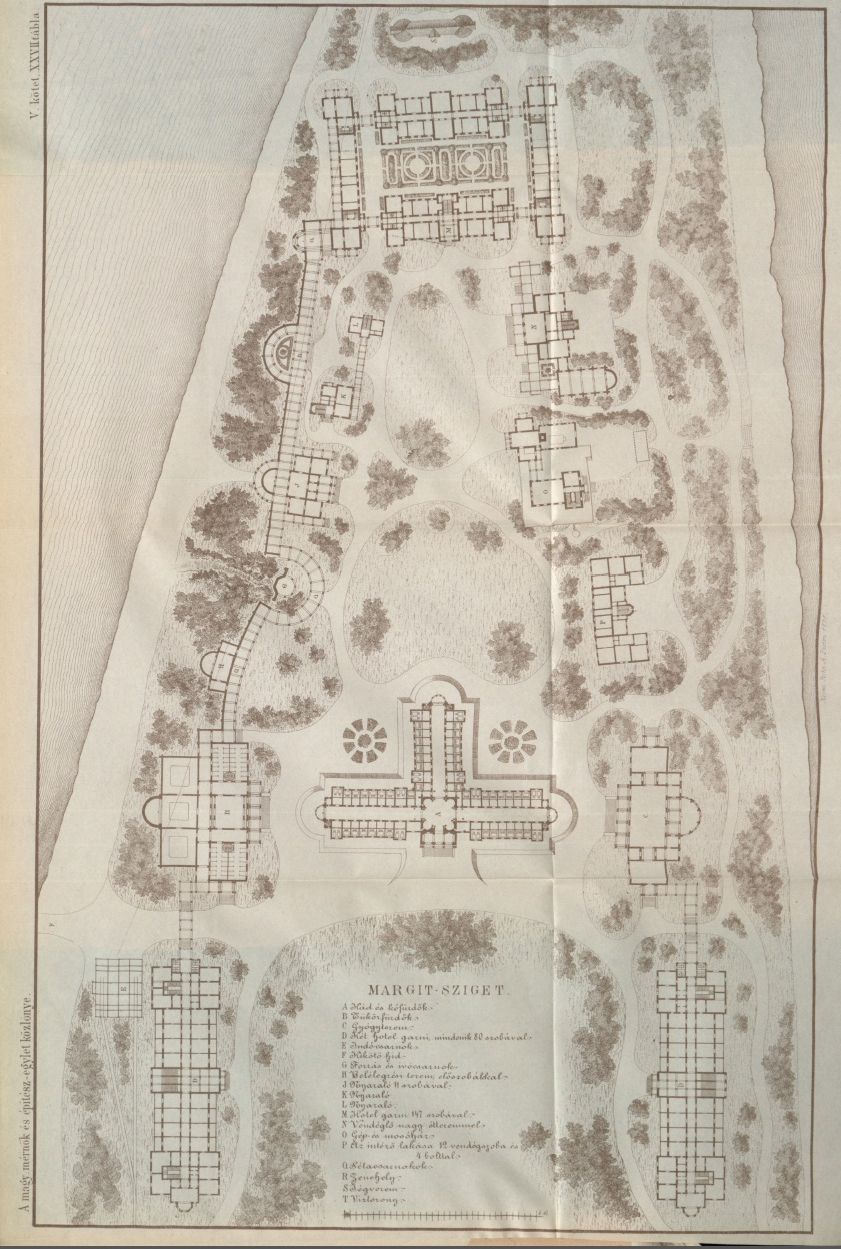

After Zsigmondy managed to explore the thermal water sources, Archduke Joseph Karl commissioned Miklós Ybl to design a large bath complex. Ybl wanted to build the bath complex in the middle of Margaret Island, but it would have been more difficult to get thermal water here from springs at the northern end of the island. Thus, the architect eventually designed the bath and the buildings attached to it further north.

Site plan of the bath, now planned for the northern end of Margaret Island. The site plan was published in the Magyar Mérnök- és Építész- Egylet Közlönye [Gazette of the Hungarian Association of Engineers and Architects] in 1871 (Source: Ybl Miklós Virtual Archive)

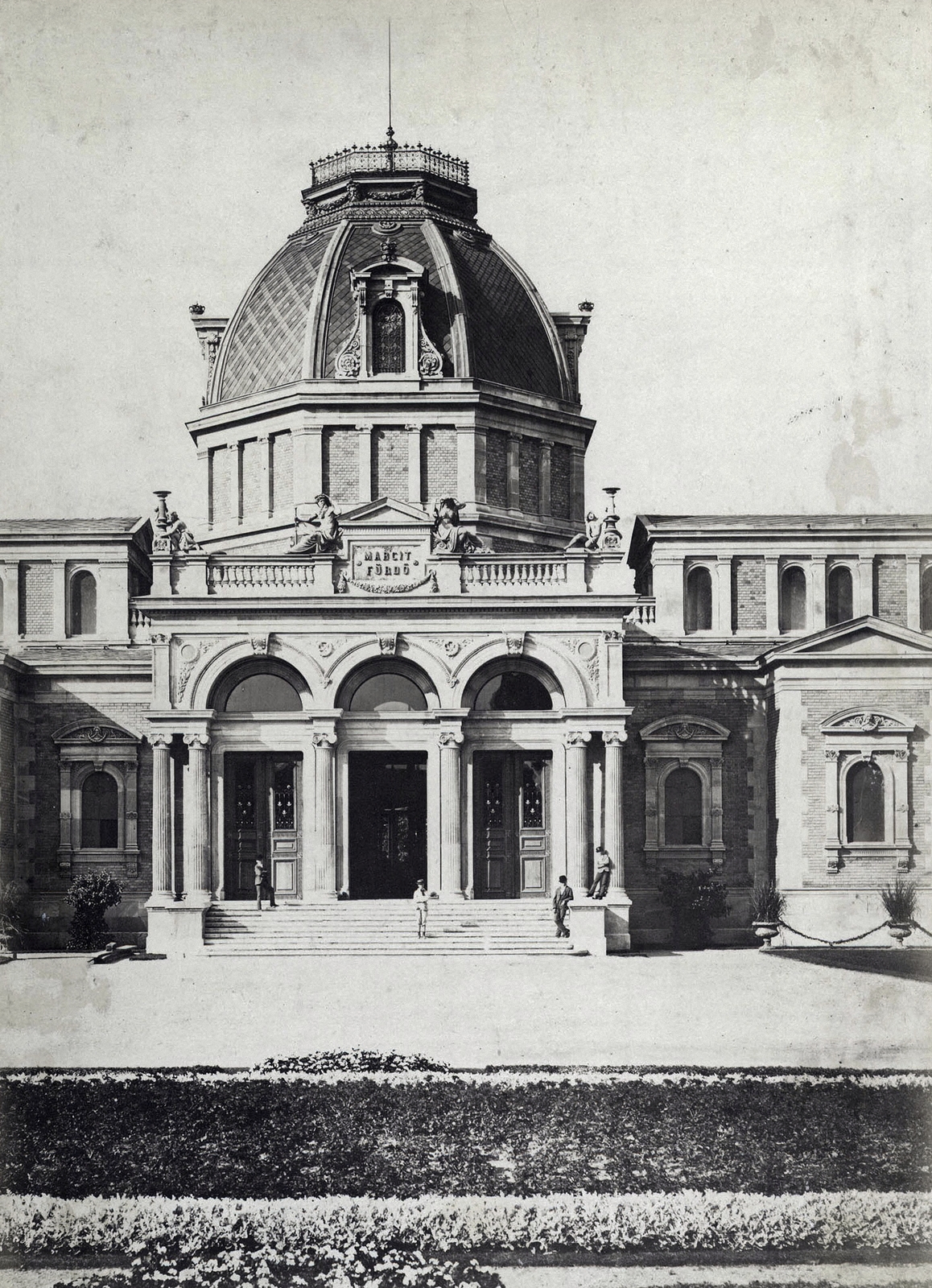

Construction of the bath complex began in 1868. The central building, the Margaret Bath, was completed in 1869. Miklós Ybl, designed the bath complex - and also the bath itself - in the Neo-Renaissance style, and according to some sources, it became one of Ybl's most harmonious buildings.

The entrance to the Margaret Bath circa 1876, photographed by György Klösz. The central element of the building was the octagonal dome, which was held by 16 columns and decorated with frescoes from the inside (Source: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.092)

The Margaret Bath was located in the southern part of the bath complex. In the center of the building, consisting of three basilica ships with a “T” floor plan, was an octagonal dome held by 16 brown marble columns. Through the entrance, guests arrived in the foyer, where the already mentioned 16 columns held the dome. From here, corridors ran in three directions, with bath cabins on either side. In the left wing were the bathtubs, and in the other two wings were the stone, marble, porcelain, and mirror baths. Each cabin also had a shower, clock and artistic furniture.

The northern facade of the Margaret Bath between 1880 and 1890, photographed by György Klösz. In front of the entrance of the bath there is a drinking fountain, while behind it there is a flower clock (Source: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.06.032)

The northern facade of the Margaret Bath between 1880 and 1890, photographed by György Klösz. In front of the entrance of the bath there is a drinking fountain, while behind it there is a flower clock (Source: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.06.032)

The Margaret Bath complex was so popular that until the wing bridge of Margaret Bridge leading to the island was completed in 1900, constant steam boat services took those waiting to relax and heal from both sides of the Danube. The bath suffered significant but easily repairable damage during the siege of Budapest in 1944-1945, but it was demolished in 1958 to allow a more modern bath and hotel (called a spa hotel) to be built on its site, which was handed over in 1979.

The Erzsébet Sósfürdő [Elizabeth Salt Bath]

Hungary, including Budapest, is rich in thermal waters due to its geographical location. To exaggerate a little: whoever digs deep enough is sure to come across thermal water sooner or later. This is how Ferenc Unger, a pharmacist, found the Elizabeth spring in Kelenföld in 1855. The pharmacist had a bathhouse built for people suffering from a variety of ailments (including digestive and gynecological problems, skin diseases, hemorrhoids) in hopes of recovery.

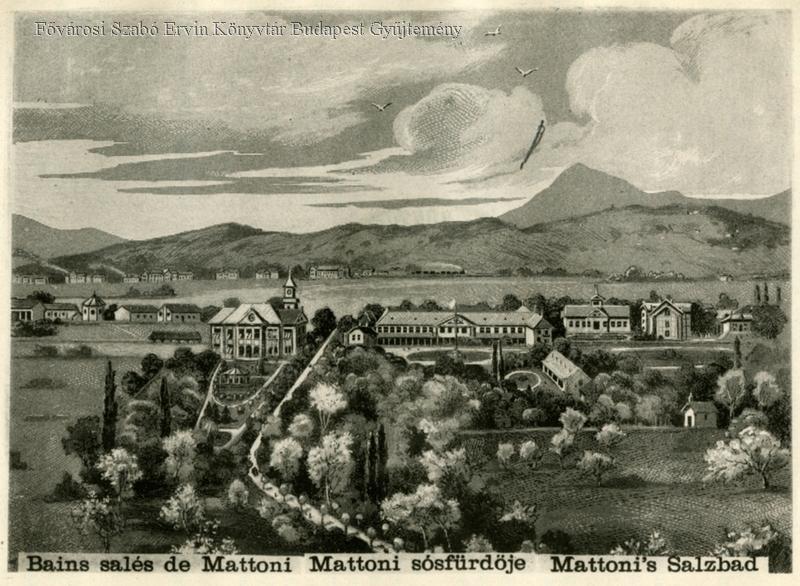

Ferenc Unger died in 1865, and after a small detour, in 1881 his bath was got into the hands of a merchant, imperial councillor, Henrik Mattoni, who at that time already owned several baths in the Czech Republic (including Karlsbad, now Karlovy Vary). Mattoni decided to renovate Ferenc Unger's bathhouse and asked Miklós Ybl to make the plans. The reconstruction took place between 1881-1882.

Mattoni's Elizabeth Salt Bath on an engraving made in 1890 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Ybl expanded the existing bathhouse with two new wings, which included 44 bathtubs, four marble spa pools and showers. There is a hotel next to the bath, in which some the rooms had a private bathroom. A restaurant, a medical apartment and a chapel was also built. Some of the buildings and pools in the spa complex were connected by paved promenades and a park.

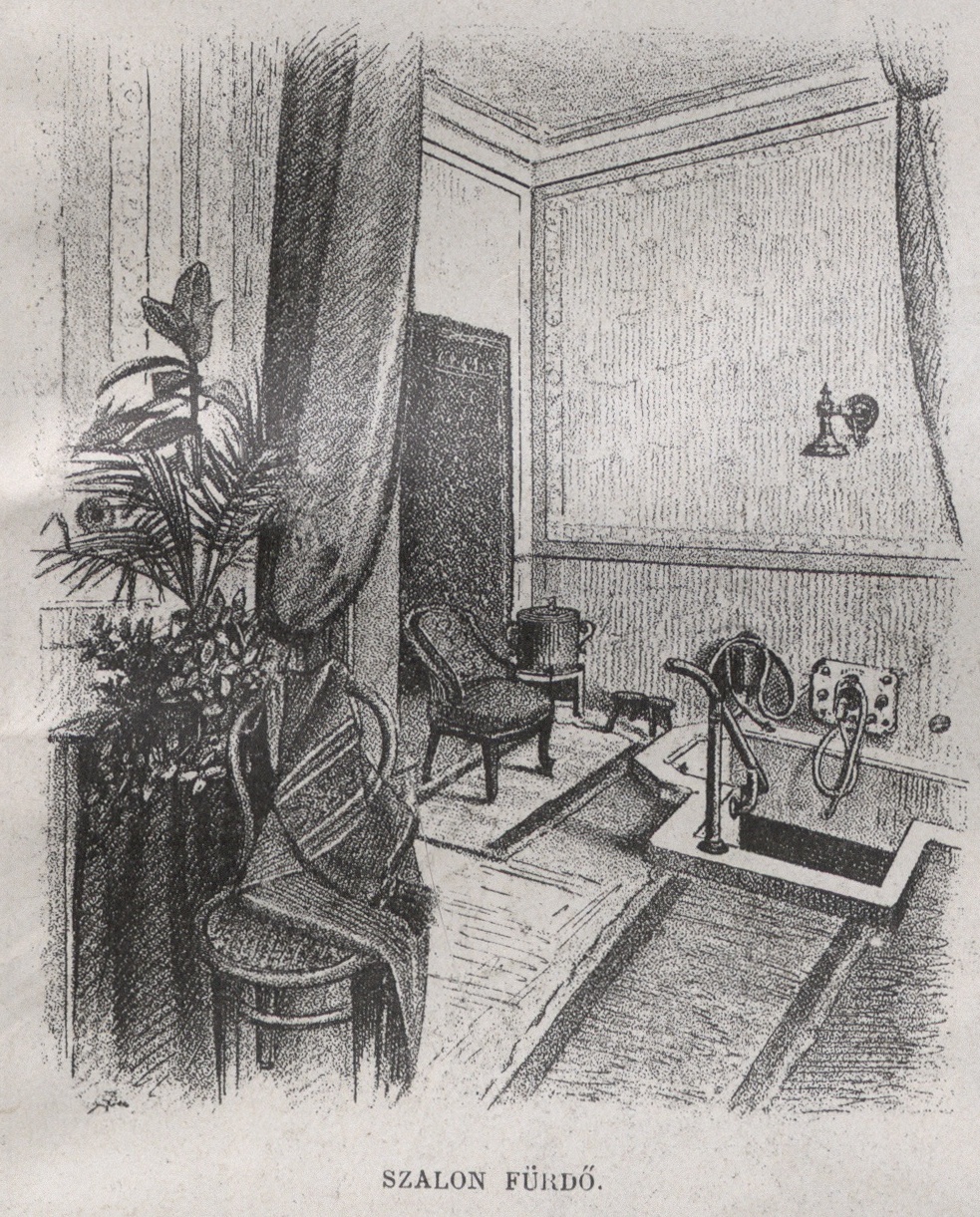

A so-called saloon bath from the Elizabeth Salt Bath from the 9 April 1887 issue of the magazine Ország-Világ (Source: Ybl Miklós Virtual Archive)

The thermal water was brought to the surface by steam pumps and used not only for bathing but also for bottling; a significant part of it was exported abroad.

%20(1).jpg)

The bathhouse on a postcard after 1900 (Source: Ybl Miklós Virtual Archive)

After the Ybl reconstruction, the Elizabeth Salt Bath attracted a lot of visitors. Its popularity rivaled that of the famous Buda baths. Although barely damaged in World War II, no money was spent on its maintenance and renovation, and eventually the buildings of the former bath were demolished in 1954. Today, St. Emeric Hospital is in place.

The Hungária Bath

At the dawn of the Hungarian Reform Era, András Gamperl, a silk merchant, lived in Pest, Nyár Street. In 1827, while digging a well, he found a cold water spring, which was rich in minerals, and then in the same year he built a bath on the lot. Although the great flood of Pest in 1838 destroyed the bath, it was rebuilt in the early 1840s due to the needs of those living in the area.

The colloquial language of Pest gave the name Hungária Bath at that time, which in the 1850s awaited its guests with 15 bathtubs in 12 rooms. The Nyár Street wing of the bath was rebuilt around 1890 according to the plans of architect Imre Novák. Although the bath was already popular at that time, it only became really popular later.

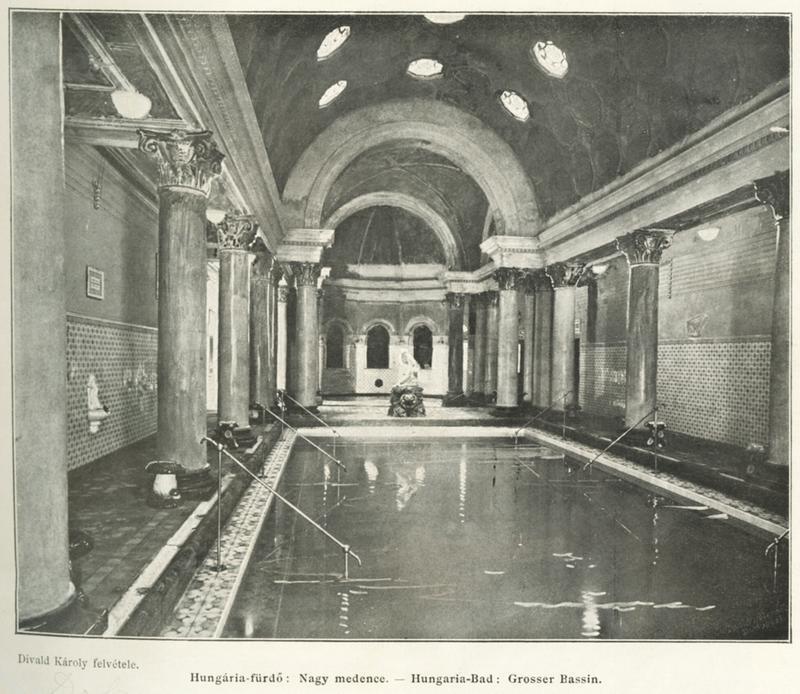

The large pool of the Hungária Bath in 1904 by Károly Divald (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

After the turn of the century, the owners of the bath asked Emil Ágoston to redesign the building. The Art Nouveau building dreamed up by the architect, with its ornate main entrance at 44 Dohány Street, was finally completed by 1908. In addition to following the fashion of the time in its appearance, it also had a number of technical innovations. The Hungária was a bath complex, in which 4 steam baths, 60 bathtubs, a thermal pool, a swimming pool, two public - specially for those with modest income- baths, a guesthouse, a hotel and a laundry awaited the guests. Moreover, even a panoramic sun terrace was included in Hungária's repertoire.

Above the pools covered with dark blue majolica, there was a glazed roof that could be opened and closed by an electric motor, which was opened in good weather for guests to bathe in the open air. Thus, it is not surprising that among the guests of the bath, writers and poets based in the nearby New York café appeared more and more often. By 1910, the Hungária Bath had practically reached its peak of popularity.

Following the plans of Emil Ágoston, by 1908 one of the masterpieces of the Hungarian Art Nouveau was born with the reconstruction of the Hungária Bath. A photo of Mór Erdélyi was made around 1910 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

In the meantime, however, the comfort level of the capital's housing stock has improved, so that fewer and fewer people needed to go to public baths for their hygiene. Moreover, in the 1910s, the intensifying scandals also damaged the bath's reputation. For example, in 1912, a guest drowned in one of the pools because the staff was unable to provide professional assistance. Increasingly, people began to use the bath as a meeting place or as a venue for one-time rendezvous.

Eventually, in 1920, it became the property of a bank, which continuously transformed the bath: first into a cinema and then an apartment building and a hotel. The hotel that opened here was called the Continental.

Due to the lack of renovations, the condition of the building deteriorated after the Second World War. This can be clearly seen in the relief above the main entrance of the Hungária Bath in 1984 (Source: Fortepan / No.: 108124)

The building survived the siege of Budapest, and in it - in addition to the Continental - short-lived theatres followed each other. The hotel closed in 1970, and the building complex began to quickly deteriorate. Following the change of regime, it was first given monument protection status and then transferred to new owners during privatization. A significant part of it was demolished, only the facade of Dohány Street remained. In the mid-2000s, the torso left of the bath changed hands again. The new owners, with the renovation of the remaining parts, designed a hotel on the site, which opened in 2010 under the name Hotel Continental.

Cover photo: The main facade of the Margaret Bath was made around 1878 by György Klösz (Source: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.090)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration