Most of the Hungarian press acknowledged with appreciation 135 years ago that a 38-year-old man had been appointed Minister of Public Works and Transport. The former portfolio of István Széchenyi fell into the hands of a man who not only claimed the transport and economic program laid down by the 'greatest Hungarian', but was able to further develop it in an understandable way. Gábor Baross, as he was the young minister, took over the management of Hungarian transport policy on 23 December 1886, 135 years ago. After his appointment, on 31 December 1886, the Nemzet wrote:

“The appointment of Gábor Baross in the field of our transport policy marks an event that will be welcomed by all objective judges of our economic and financial interests, especially in the current crisis; in the meantime, the personal moments inherent in this appointment must also resonate enthusiastically. Especially in the heart of the party in whose ranks Baross has run a short but shiny political career so far.

Neither prestigious origins nor higher connections or a bright wealth helped Gábor Baross rise in this field. He came to parliament eleven years ago as a young, almost unknown member, from a Highland county and on his own, through his excellent talents, amazing workforce, and perseverance, he soon, at a young age, became one of the leading figures in our political life.”

Gábor Baross on the painting of Miklós Barabás

Baross's activity was not limited to Budapest, as he wanted to create a transport system at the national level that served Hungary's economic interests. What were his main goals? Efficient, largely state-owned and cheap railways, an orderly telegraph, post and telephone network, an orderly road system, the development of a Hungarian seaport - i.e. Rijeka - and a navigable Danube, the latter meant further regulation of the Iron Gates.

It was no coincidence that Baross was appointed to this important post in 1886, having been a Member of Parliament for 11 years and Secretary of State for Transport since 1883. Baross, also known as the iron-handed minister, dictated an incredible pace of work, and nothing distracted him from his main goal, which was to create a national transport and communications policy serving the Hungarian economic policy, without being influenced by personal or partisan interests.

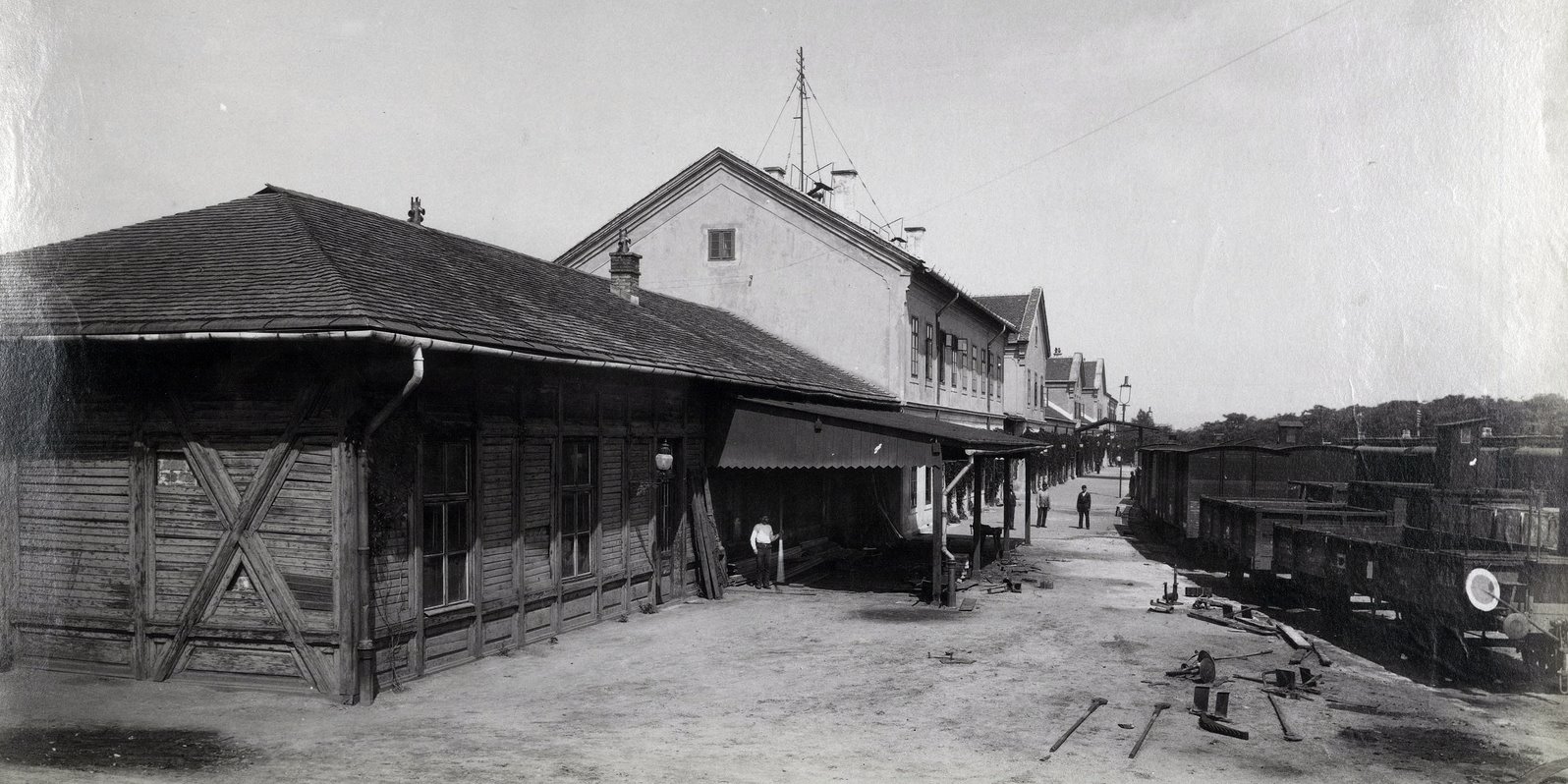

One of his most important achievements was the creation of affordable rail transport for all. It was possible to reach the capital cheaply from the countryside. Józsefváros Railway Station, the first MÁV railway station in Budapest during the Baross Ministry (Fortepan, Budapest Achives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.07.093)

The task of regulating the Iron Gates was assigned by the Congress of Berlin in 1878 to the Habsburg Empire, including Hungary. The work took many years and was a major technical feat. The country carried out the huge task under the leadership of Baross, making the Danube navigable up to the mouth most of the year. Of course, this was also important for the trade of Budapest, as the products of the Budapest plants had easier access to the world market.

Although his ministerial activity was of national significance, he knew that a strong country needs a strong centre, so many of his measures resulted in the strengthening and development of Budapest.

The most important tool for this was the introduction of a zone system. The basis of the new railway tariff, which came into force in 1889, was to divide the railway lines into certain kilometres and zones. In other words, the tickets were not for the given settlement, but for example between 60 and 80 kilometres, no matter exactly where someone was travelling. In addition, rail tickets could be purchased at major post offices.

In parallel, ticket prices were reduced to a fraction. However, long-distance travel was explicitly supported, as the ticket price did not change after 225 kilometres. But there was a twist that helped the interests of Budapest. The principle was that above 225 kilometres, no matter where one travelled, the ticket cost the same. Unless someone travelled through Budapest.

Budapest was definitely a zone border. As virtually all railroads ran in here, passengers in most cases passed through the capital. In this case, a zone ticket from the station of departure to the capital had to be purchased, and those who travelled from here had to buy another ticket from the capital to the destination (the ticket was issued that way at the time of departure). So, if the destination happened to be Vienna, the passenger had to pay for a ticket to the Hungarian capital, and then had to pay another 225 kilometres from Budapest.

So it was cheaper to travel to Budapest than to Vienna, i.e. it was more worth shopping in the Hungarian capital. The following saying is attributed to Baross: "I want the wives even from Brasov to come to Budapest to buy a hat!"

Already in 1898, a statue was erected in Budapest, in front of the Keleti (Eastern) Railway Station, of the deceased iron-handed minister (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.08.088)

As a result of the provision, the country was put on a train. The railway became accessible and affordable for everyone, so people travelled en masse, not only to the nearby villages, but also to Budapest to do business and buy things that might not have been available elsewhere in the countryside.

Despite the fact that Gábor Baross's activity was not closely connected to Budapest, its impact on the capital was significant, it is no coincidence that a total of 13 streets, squares or parts of the capital are named after him.

Baross was unable to see his work completed, as he died of pneumonia in 1892 at the age of 44.

Cover photo: Baross Square, with the central house of MÁV, i.e. the Keleti (Eastern) Railway Station (Source: Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.06.060)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration