Although the pandemic has pushed back international tourist traffic to Budapest, everyone is well aware that the Hungarian capital is a very popular destination for foreign travellers. This was already the case between the two world wars, which the governments at the time and the city administration were trying to take advantage of. In addition to the benefits to the national economy, they also saw the opportunity to campaign for a revision of the Trianon peace treaty. Thus, tourism was considered to be a determining factor and efforts were made to provide the highest possible quality services to visitors.

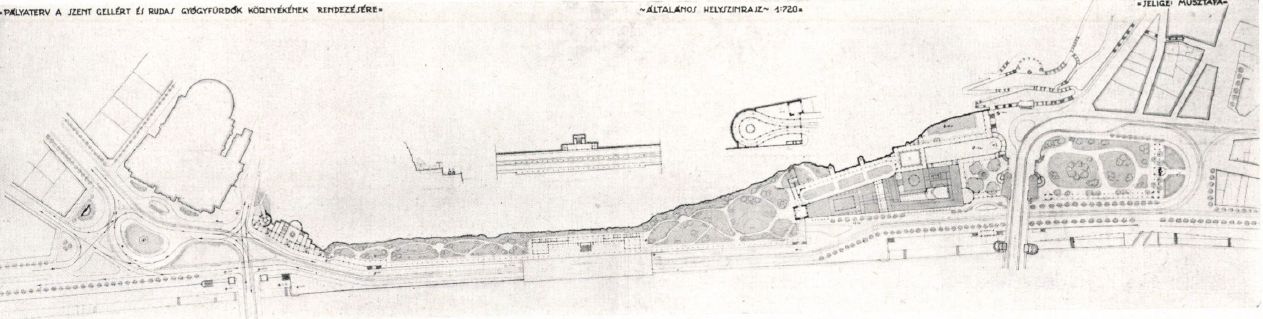

Even then, the baths attracted the most foreigners, so the city administration would have connected the baths south of Várhegy (Rác, Rudas and Gellért) with promenades in Buda, thus establishing a huge, park-based bath complex. An architectural competition was also announced, most of the plans received led the promenade between Rudas and Gellért along the banks of the Danube, and diverted traffic to the lower embankment.

Blueprint on the connection of the baths on the Buda side (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 5, 1931)

Initiatives were also taken to develop the Danube bank in Pest, but these were no longer for the Cabinet but for private individuals. In 1925, Dr. János Fritz, chief physician, proposed the erection of a skyscraper on the Danube Promenade, in which the thousand-year-old Hungarian history would be presented to tourists. He chose the location because, in his opinion, it would complete the rectangle, the north side of which is formed by the Chain Bridge, the western side by the Buda Castle's ensemble, and the southern side by the Erzsébet Bridge.

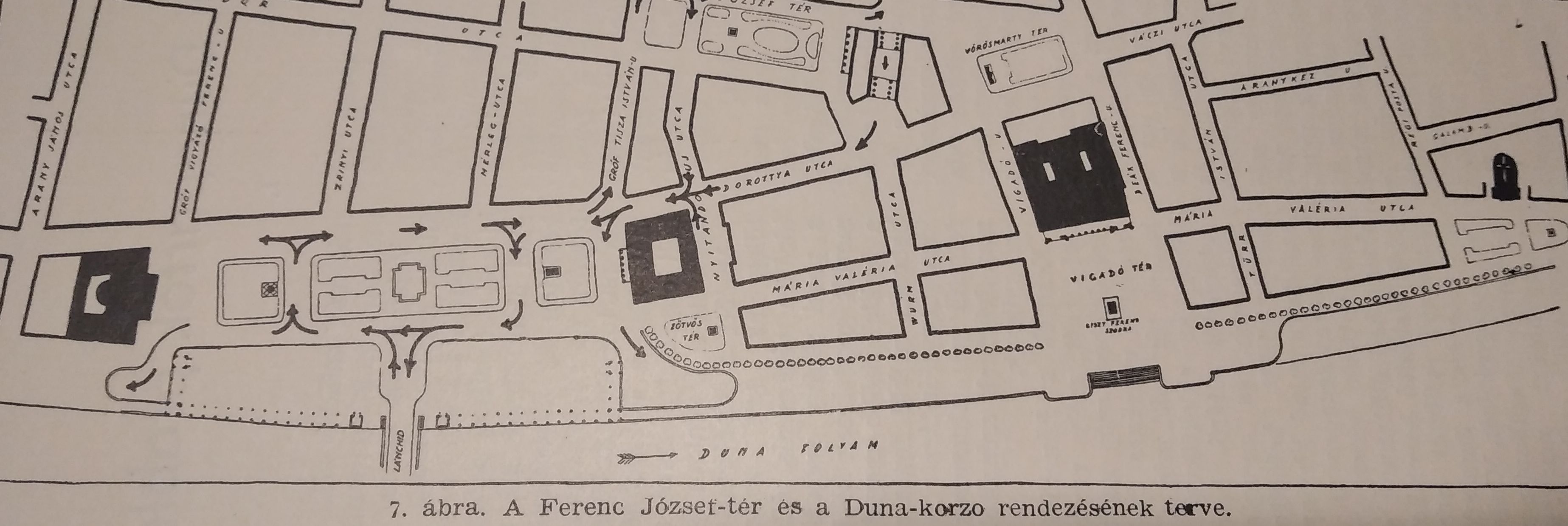

Jenő Lechner - Ödön Lechner's nephew - also liked the idea and made plans for it. However, he pushed the site lower: he would have built the tower on the southern section of the former Ferenc József Embankment, along today's Belgrád Embankment. The buildings of the Promenade still showed a nice uniform picture, but the part south of the Erzsébet Bridge was much more confusing, so it would have been demolished with a lighter heart. He would have turned the promenade into a bath promenade like the one on the other side.

Jenő Lechner: The layout plan of Ferenc József Square (today's Széchenyi István Square) and the Danube Promenade (Source: Dr. Jenő Lechner: On the urban planning tasks of Budapest, 1938)

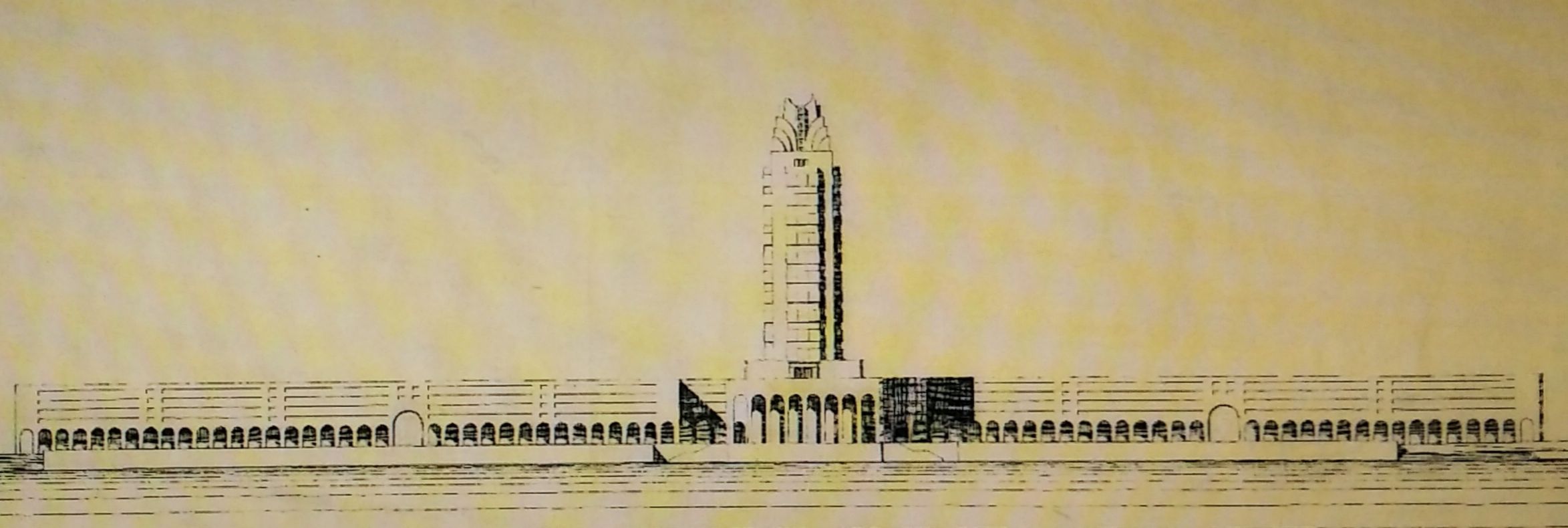

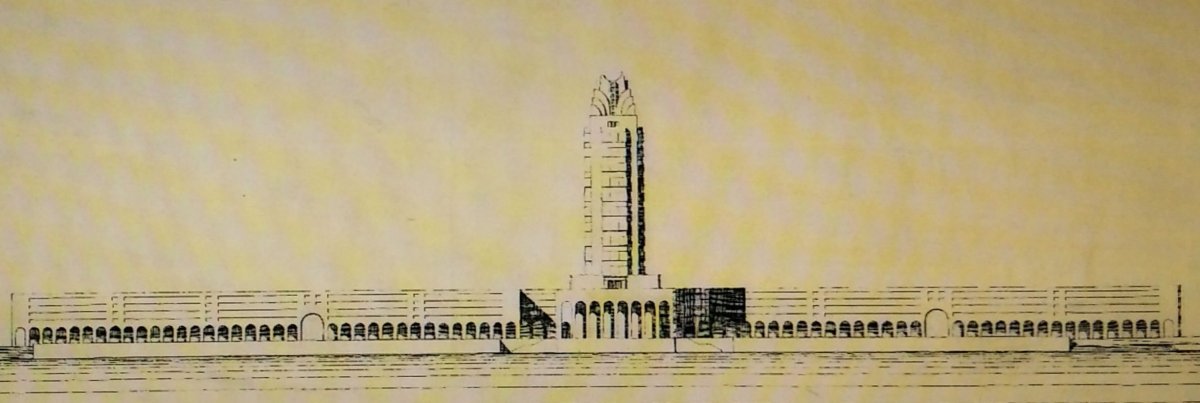

According to Jenő Lechner's idea, he would have erected a single coherent building complex on the banks of the Danube between the Erzsébet Bridge and the Ferenc József Bridge (now the Liberty Bridge). The 530-metre-long, arcaded giant reflects the influence of the Italian novecento. Yet, despite its huge size, it would have served only as a background for the 130-metre-high Tower of Hungarian History, which was the main attraction.

On the ground floor of this would have been a central dome hall, the crypt of the unnamed heroes, and the monument to Pope Sylvester II donating the Holy Crown. On the first four floors, Lechner would have set up an exhibition and shops of Hungarian industrial and artistic exports. Above them, the events and objects of the millennial history would have appeared on ten levels, so each level would have presented a century. At the top was the Chapel of the Hungarian Credo, which would have been surrounded by lookout terraces.

.jpg) The southern section of the Ferenc József Embankment in 1939 (Source: Fortepan/No.: 76656)

The southern section of the Ferenc József Embankment in 1939 (Source: Fortepan/No.: 76656)

Jenő Lechner's plan (Source: Kiscelli Museum, Budapest History Museum)

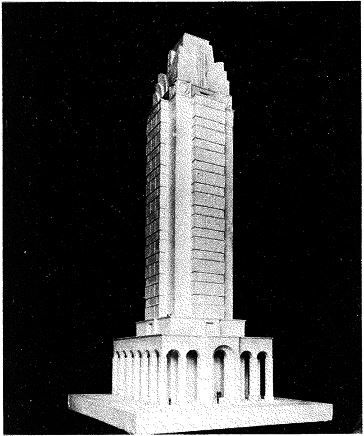

The building, according to the plans, was closed by a simplified merlons: huge, petal-shaped merlons rose behind each other at the four corners. With these, Jenő Lechner referred to the Highlands' renaissance style of the 16-17th century, which, according to him, is a typically Hungarian style - so he wanted to shape the skyscraper architechtually into a Hungarian one in addition to its content.

Model of the Tower of Hungarian History from 1930. The building would have presented the thousand-year-old Hungarian history to tourists (Source: Kiscelli Museum, Budapest History Museum)

This was not the first time he had placed elements of classical architecture on a modern high-rise building: in 1922, he made a similar plan for the headquarters of the Chicago Tribune daily. In the United States, the Hungarian motifs were less understandable, but in any case he received a certificate of appreciation from the press company for the plan.

Jenő Lechner's plan for the Chicago Tribune headquarters received an award from the American press company (Source: Kiscelli Museum, Budapest History Museum)

The plan of the Tower of Hungarian History actually merged the ordinary functions of a tourist service centre and the lofty functions of a national pantheon. Revenues from rents and tickets would have been used to support Hungarian children, i.e., the future.

Lechner intended the building primarily for foreign tourists, so they could learn about the history of the Hungarians, how the nation did everything they could to protect Europe, and how unfair the Trianon peace treaty was. The tower would have achieved a definite propagandistic goal as any representational investment between the two world wars. At the same time, with its size, it also wanted to express the strength that lived in the Hungarians, thanks to which it was able to stand up even after such a historical catastrophe.

Cover photo: Jenő Lechner's plan (Source: Kiscelli Museum, Budapest History Museum)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration