This is the first such tall building in Budapest, but in fact, a building taller than 100 meters could have stood in the middle of the capital for almost 100 years. Let's see what plans were born in Budapest in the past, could our capital have had a skyscraper before?

The first really tall building in Budapest was the dome of the Parliament and the dome of St. Stephen's Basilica, both of which are symbolic 96 meters high.

In the 19th century, no higher building was planned for Budapest (or in fact, there was a bridge, an arch bridge leading from Pest to the top of Gellért Hill), but in the first half of the 20th century, bold plans were made for high-rise buildings in Budapest.

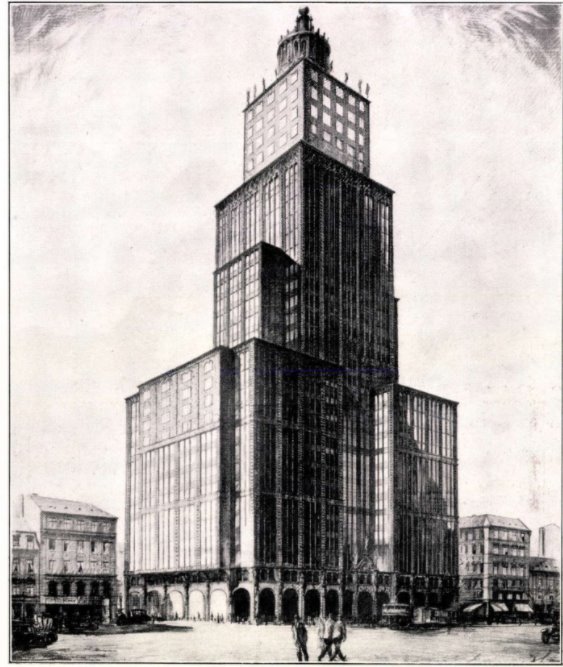

The giant designed by Hugó Gregersen for the Inner Ring Road (Image: Magyar Építőművészet, No. 5-6, 1928)

These plans were based on two main goals, one was to alleviate the shortage of housing in the city, and the other was to build the new city hall of Budapest. Of course, with the tower blocks, the designers also wanted to bring in modern, then general architectural ideas.

The first major tower building plan we should mention would have been on Inner Ring Road, next to the Anker House. It was designed by Hugó Gregersen, who designed a 27-storey building here in 1927. Not only would the house have been tall, it was also a large area, so large that the Anker house next to it would have been practically dwarfed.

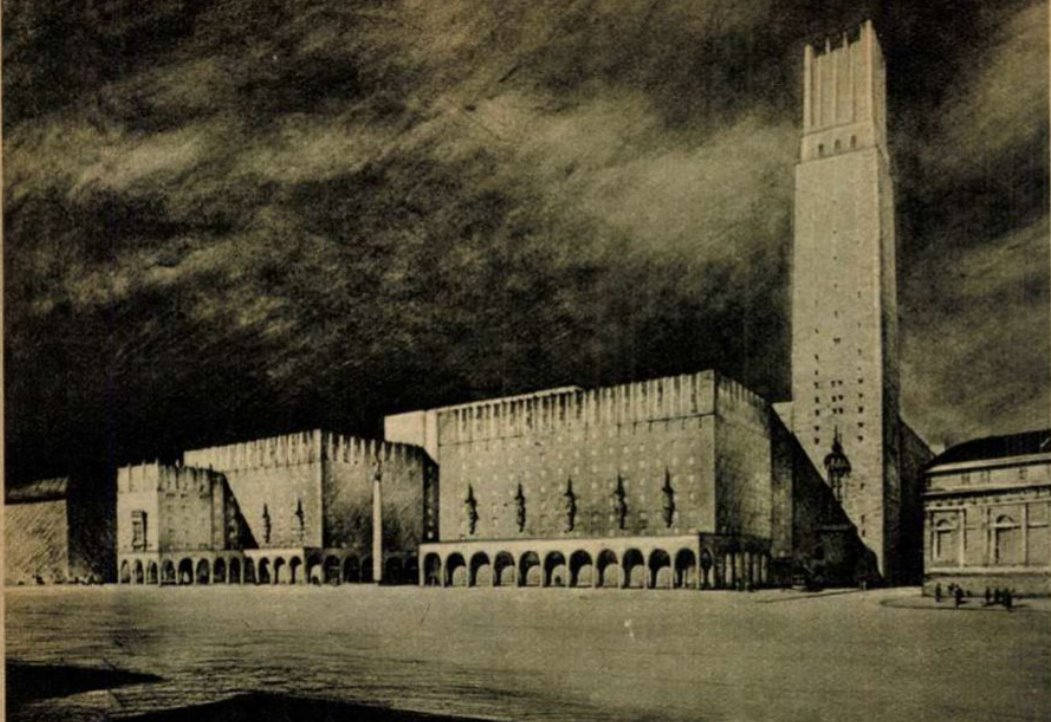

This was not the only tower house plan for Hugo Gregersen, because in 1928 he also designed a grandiose building to replace the Rókus Hospital, which would have been even taller, 34 storeys high.

The 34-storey tower planned to replace the Rókus Hospital (Picture: Magyar Építőművészet, No. 5-6, 1928)

Already during World War I, and then between the two world wars, the reconstruction of the surroundings of today's Inner Ring Road, Deák Square and Madách Square was constantly on the agenda, as well as the creation of the new centre of Budapest, and building a new city hall. In connection with the new inner city, the construction of a new avenue was constantly on the agenda, which would have started from Inner Ring Road, today's Madách Square. The small planned estuary of the new, planned Erzsébet (then Madách) Avenue was definitely made even more accentuated by a spectacular building.

Even before World War I, a number of ideas were born for the city hall and the dominant buildings planned at the end of the new boulevard, several of which suggested tall towers. The zoning plan adopted in 1929 in the vicinity of Erzsébet Square already supported high-rise solutions, and accordingly, a number of proposals were made that would have placed real high-rise buildings here.

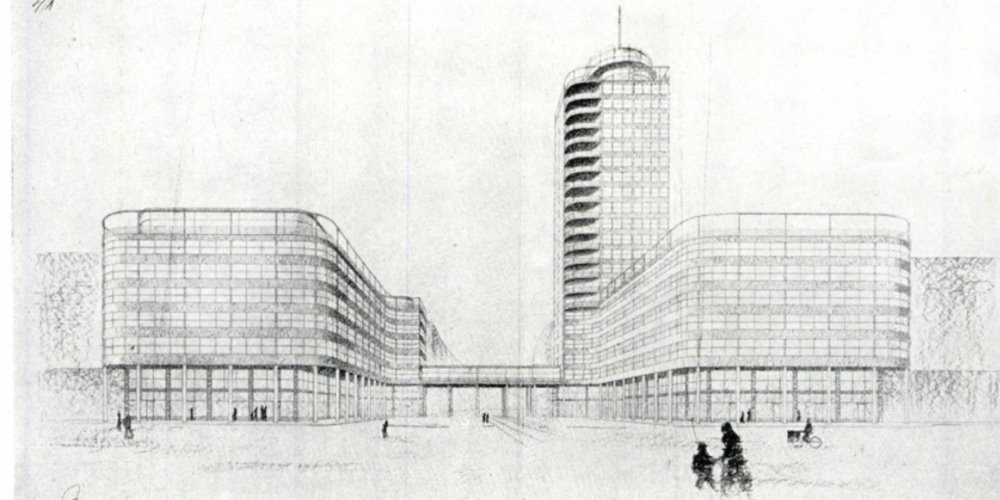

The aforementioned Elizabeth Avenue would have started from the site of the former Orczy House. As early as 1929, a design competition was announced here, in which 47 applicants took part. Hugó Gregersen again applied for this call with a skyscraper, who imagined that the boulevard would have been lined with two equally high-rise buildings. The Orczy House was finally demolished in 1936, but no high-rise buildings were built in its place.

In 1939, a number of ideas were born for the design competition of the city hall, which also included a tall building. The first prize was awarded to the joint plan of Róbert Kertész K. and Károly Weichinger and the idea of Imre Martsekényi.

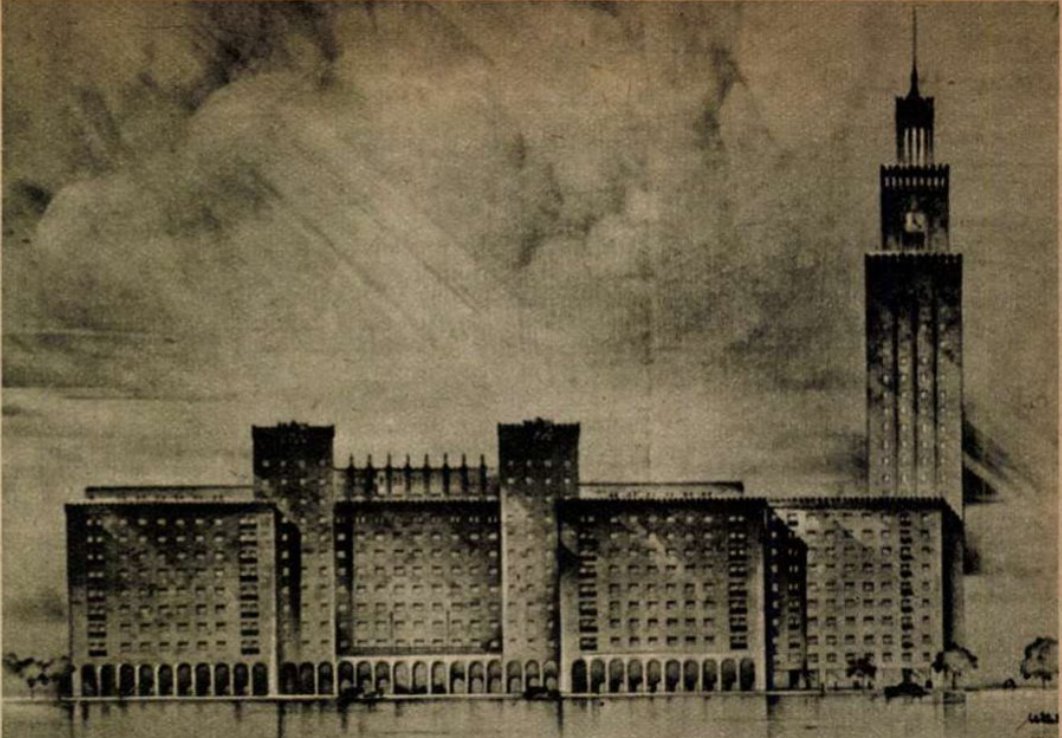

Plan by Róbert Kertész K. and Károly Weichinger (Image: Pesti Hírlap, 29 June 1940)

Róbert Kertész K. and Károly Weichinger envisioned a 30-storey clock tower between today's Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Road and the planned Erzsébet Avenue. The 29 June 1940 issue of Pesti Hírlap commented on the plan:

“Setting the city hall tower, which is about 120 m high, in the axis of the Vilmos császár Road and the smaller square at the bottom of the tower was extremely successful. The modern needs of transport have been fully met. Car parking spaces and underground car parks and garages are plentiful. The internal needs of both the city hall and the factory headquarters were perfectly met in this plan. ”

Another idea, also awarded the first prize, is the work of Imre Martsekényi (Photo: Pesti Hírlap, 29 June 1940).

The second prize was won by Gyula Wälder, who imagined the city hall with a 100-meter tower, which would have continued the style of the neighbouring Madách houses, which were also designed by him and were already built.

Pál Forgó also entered the tender with a high-rise building, with a 25-30-storey office building that would have served as the new city hall.

However, tall towers were not only designed around the city centre. In place of Tabán, 15-20-storey residential houses were dreamed of, but the ideas were high elsewhere as well. Also in the 1930s, the idea was born to build the Tower of Hungarian History between the Erzsébet Bridge and the Ferenc József Bridge. This huge complex, designed by Jenő Kismarty-Lechner, would have stretched 530 meters long on the banks of the Danube, and the 130-meter-high Tower of Hungarian History would have risen in the middle.

In comparison, the tallest building of the era was the 70-meter-high OTI Tower on Fiumei Road, the tower of the headquarters of the National Social Security Institute, which was demolished in 1969 because bauxite concrete was used to build it.

The tallest building between the two world wars was the 70-meter-high tower of OTI's headquarters (Photo: Fortepan / No.: 92521)

Even after World War II, bombastic plans were made, such as the 140-meter-high Soviet-style tower dreamed of on the Danube Promenade in Pest, similar to the Lomonosov University building, which would have housed the offices of the Hungarian Workers' Party and the Central Palace of Culture.

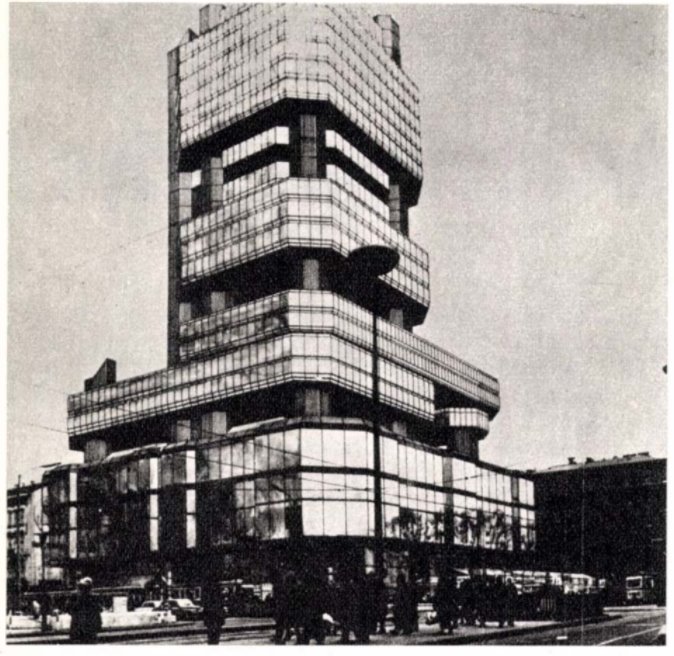

Nevertheless, fortunately, only towers such as the SOTE tower or the 15-storey high-rise building on Alagút Street and the high-rise buildings of 15 storeys and higher were built on housing estates. Of course, there were plenty of plans, as the new headquarters of the MTESZ, the Műszaki és Természettudományi Egyesületek Szövetsége [Union of Technical and Natural Science Associations], was planned to be built in Astoria, for example. The first prize in the competition announced in 1970 was the not very high house dreamed up by Lajos Zalaváry and his designer colleagues, and the 100-meter-high building designed by Lajos Horváth and Ferenc Marussy.

MTESZ's 100-meter-high headquarters plan at the Astoria (Image: Budapest magazine, December 1970)

After the change of regime, the high-rise design fever flared up again. Real skyscraper plans were born, and it was discussed that the northern part of Csepel would be developed as a mini Manhattan, but high-rise buildings were planned for the Pest end of the Árpád Bridge, as well as for South Buda.

At the end of the 2000s, a 150-meter-high tower house was planned next to Őrmező as a member of a group of 4-10 tower buildings. The Budapest ONE office building has now been built on the site.

Today, in principle, it is not possible to build a real skyscraper in Budapest, the Mol Tower could only be built with a unique permit. To this day, there is a debate among laymen, but also between architects and urban developers, about the need to build high-rise buildings in a historic city.

This will be the first in Budapest, while real skyscrapers grow one after the other in Warsaw, for example, the Warsaw Tower, which is currently under construction, will be 310 meters high.

Cover photo: A 1930s idea, Plan 930 for the City Hall (Tér és Forma, No. 10, 1930)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration