In the neighbourhood of Népliget is the Northern Maintenance Depot, whose Diesel Hall has been one of Hungarian State Railways' (MÁV's) most important railway workshops for decades. In 2021, the Hungarian Museum of Technology and Transport managed to find a new home in this building, which debuted its first temporary exhibition, Once There Was The Északi, last summer.

The Diesel Hall, another room of which now presents the unrealised developments (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

In the same building, in another room of the Diesel Hall, another interesting exhibition was opened about the unrealised developments in Budapest. On the day before the opening, on 20 June 2022, the director general of the institution, Dávid Vitézy, presented the periodical exhibition at a press conference entitled: The Unbuilt Budapest.

The exhibition presents development ideas that have not been realised (Photo: Museum of Transport)

Regarding the unrealised improvements, the director general said that the selection criteria were to include plans that were still relevant, also they wanted to present the alarmingly bizarre but previously serious ideas.

In the unique Diesel Hall, Director General Dávid Vitézy told the press about the new exhibition (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

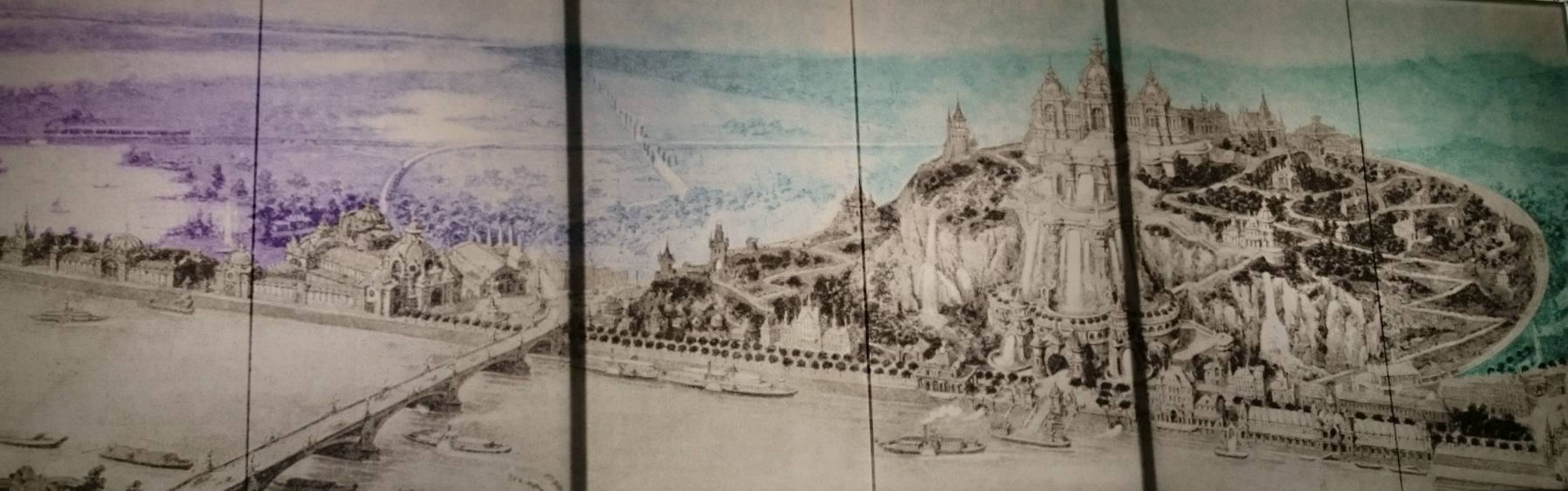

One of the development ideas still topical is the Gellért Hill funicular, one of the earliest plans of which dates from 1892: the hair-raising idea of Sándor Straub and Gyula Kolbenheyer would have really transformed the hill with domed halls and waterfalls.

However, there was also an idea that was very close to implementation: the construction of Ferenc Novák's plan for 1897 would have been started, but in the end neither the state nor the capital wanted to get into the realisation with public money. As we move forward in time, newer designs become more puritanical and, in terms of construction, more predictable.

Ferenc Novák's 1897 project on the upper station of the cable railway track leading to Gellért Hill (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

The plan of the millennium exhibition planned for Gellért Hill, proposed by Sándor Straub and Gyula Kolbenheyer from 1892. An electric railway would have led to the hilltop from the Rudas Bath (Photo: pestbuda.hu).jpg)

The current visual design of the Gellért Hill funicular was also presented, there will be a lookout terrace at the upper station (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

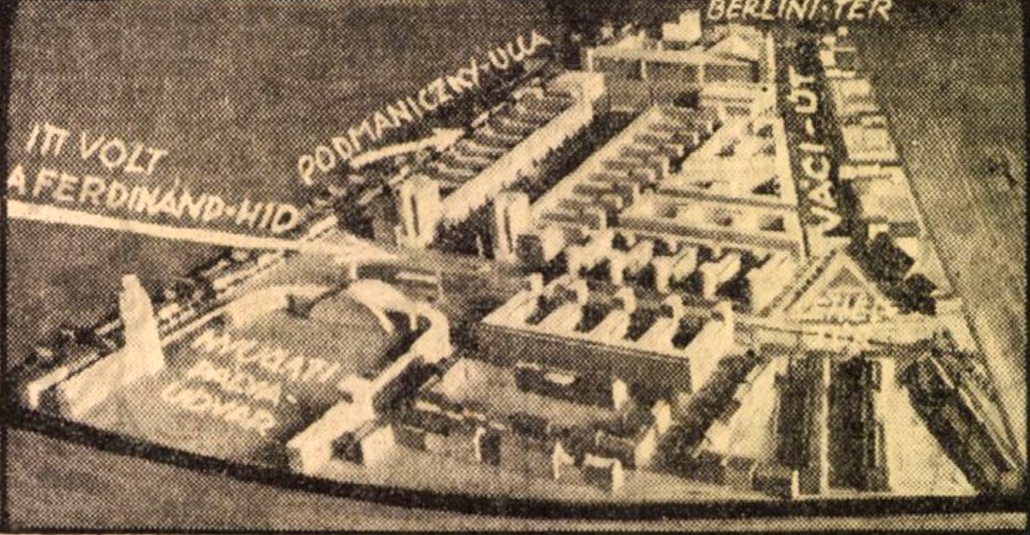

We can also learn on the spot that at the beginning of the 20th century, they wanted to relocate the Nyugati (Western) Railway Station, since it was not possible to increase its capacity even then due to a lack of space. They mainly thought of Rákosrendező as an alternative. The connection of the main railway stations by means of railway tunnel systems dates back to the late 1800s.

“So, if you take a train in Arad, Nagyvárad (Oradea), Fiume (Rijeka), Gödöllő, Soroksár or Cinkota, you can get to any part of the city and get off at one of these three stations without transfer. On the other hand, anyone who leaves Budapest can board a direct train and a direct passenger car at any city station” - read the description of Szilárd Zielinski's plan published in 1898 by the Pesti Napló. According to this, the main railway station would have been under the Astoria and in the north-south direction, underground, would have connected the railway lines on the Pest side.

Another idea about the arrangement of the area around the Nyugati (Western) Railway Station from 1938, on the columns of Friss Ujság - this can also be seen in the exhibition.

In the form of mock ups, we can also see the plans of various metro junctions (for example, similar to Deák Square, three metro lines would have met in Baross Square). We can read a lot about the metro plans of the Kádár era: according to the ideas of the time, Metro 4 would have connected Budafok with Újpalota, Metro 2 would have reached Kőbánya, and Metro 3 could have boasted a monumental length all the way to Ferihegy.

Plan of a grandiose underground station from the 1950s - read the description on the spot (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

The underpass of Felszabadulás Square (now Ferenciek Square), which was demolished in 2012, only lives in our memories (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

The transformation of Blaha Lujza Square (and other squares) into a multi-storey junction also arose: the two opposing ideas of guiding the Outer Ring Road under the ground or building an overpass at Rákóczi Road constantly clashed.

An unrealised idea: an overpass would have crossed the intersection of Outer Ring Road - Rákóczi Road at Blaha Lujza Square (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

“Plans and visions were often accompanied by heated political and press debates, and confidently announced concepts were quietly put into the desk drawer five to ten years later as the historical environment changed. There are hundred-year-old plans that we still miss; but also ideas that are fifty to sixty years old, for which it is fortunate that they have not come true” - said Director General Dávid Vitézy at the press conference presenting the exhibition.

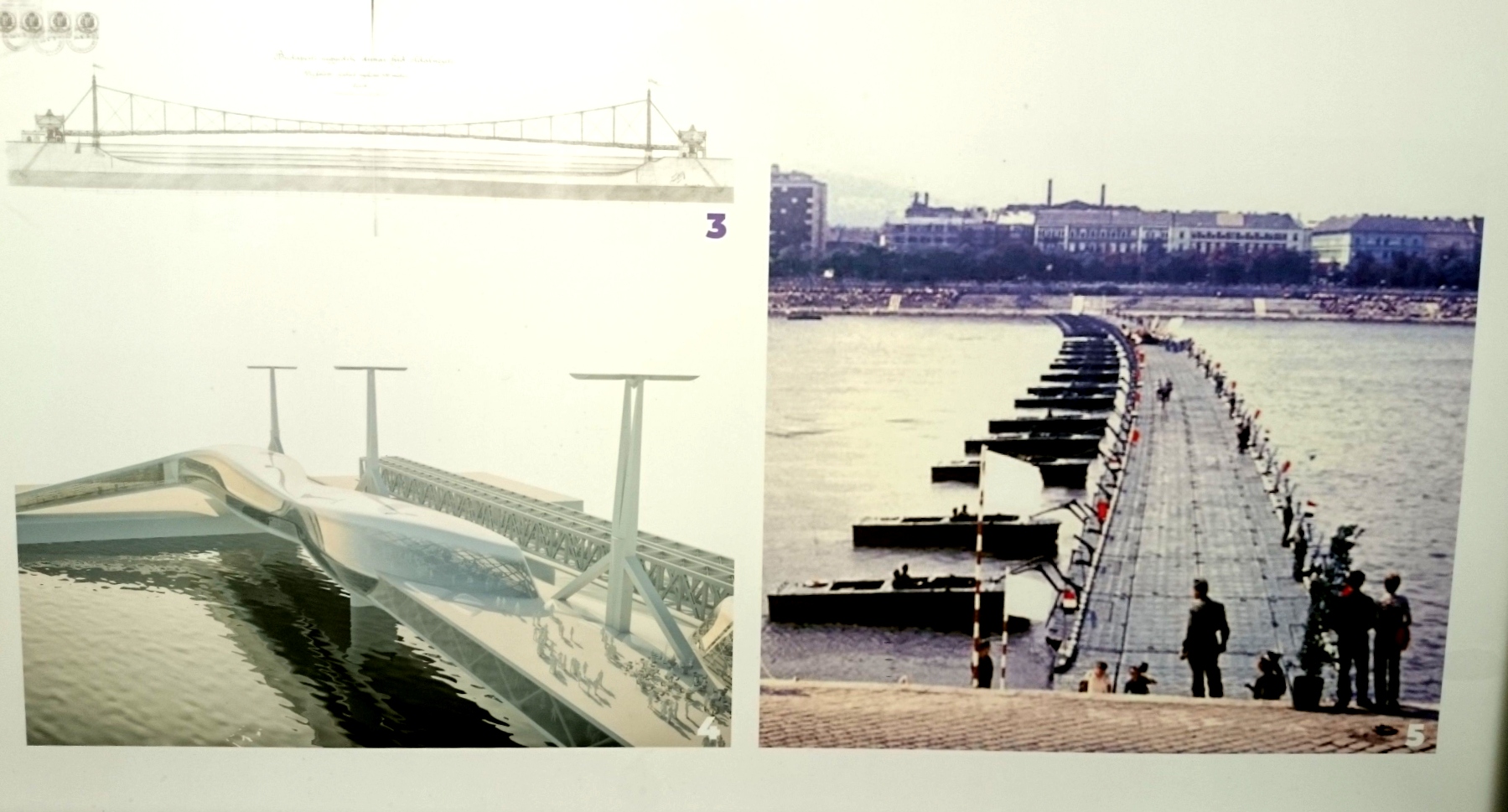

Before the Kossuth Bridge, which was built out of necessity (temporarily), the need for a footbridge at Kossuth Square was a matter of debate for decades (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

Plans for footbridges. Upper left: Szilárd Zielinsky's plan for the footbridge to be built at today's Március 15 Square from 1890, lower left: Architect József Finta would have built a multi-storey footbridge on the Rákóczi Bridge in 2016 that would have worked as a shopping street as well. On the right: a temporary bridge at Kossuth Square on 20 August 1973, at the centenary of the reunification

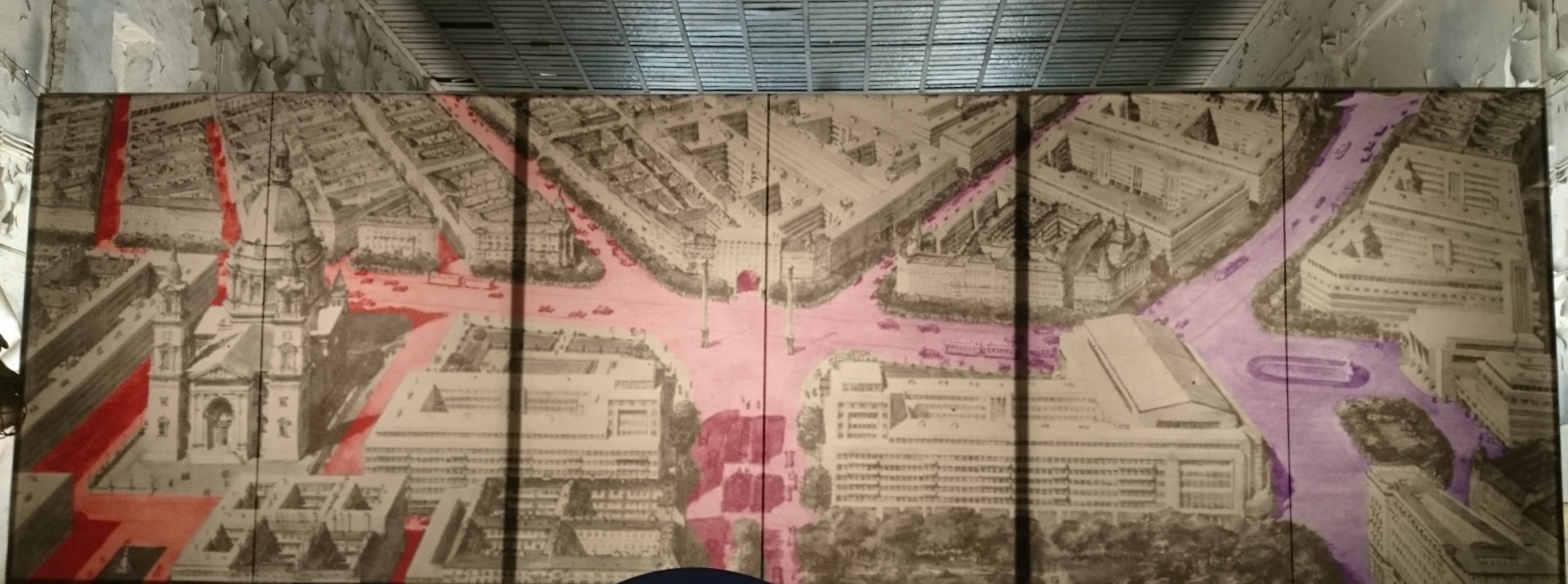

A separate chapter also presents the visions of the architect József Vágó: with his visuals made in the 1930s, he envisioned a capital rich in wide boulevards and high-rise buildings that would have addressed many problems that had remained unsolved since the previous century.

Visitors can also get acquainted with the urban development visions of József Vágó at the exhibition (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

The watercolour works of József Vágó reveal an idealistic cityscape (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

At the exhibition we learned that József Vágó expected that car traffic would be significant in Budapest in the future, so he planned wide roads. He also published a volume in 1936 on the artistic reconstruction of Budapest.

The modern tower building of the Hotel Majestic envisioned by József Vágó, compared to which the palaces of Andrássy Avenue would have looked small (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

Finally, there are development plans at the exhibition that have now been completely removed from the agenda for obvious reasons. These are mostly the ideas adopted from the United States where highways lead through the core of the capital to the detriment of parts of the historic city centre, thus putting an end once and for all to the problem of increased car traffic.

One of the key examples of this is the complete connection of the M3 motorway to today's Andrássy Avenue. As an alternative, as a result of the fierce protests, a tunnel passing from Podmaniczky Street to Alkotmány Street, under Kossuth Square (more specifically the Parliament) and the Danube, would have helped motorists to Csalogány Street in Buda.

Ford’s 1926 T-model is one of the newly exhibited vehicles. The view of the renewable museum in the background (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

Dávid Vitézy also spoke about the general future of the Museum of Transport: in the current state of the Diesel Hall, it is only suitable for organising exhibitions from late spring to early autumn, but it is a clear goal to be open all year round. The implementation of this will be assisted by the construction plans currently being prepared, which are expected to be completed by spring 2023. In the meantime, the expansion of vehicles and objects on display at the Northern Maintenance Depot is expected.

The Diesel Hall of the Northern Maintenance Depot - after it had been unused for 10 years - was doomed to be demolished, but in search of a new home, the Museum of Transport embraced the building in order to fill its spacious spaces with function and cultural content, and to renovate it in the long term, making it look like a 21st century building as well (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

In the Diesel Hall, we can not only learn about the history of the vehicle repair building complex and the everyday life of its former employees, but also the local transport history facts are presented to us. For example, the former success story of Ganz–MÁVAG, which was established in the neighbouring Józsefváros: its own manufactured railway vehicles were exported to many parts of the world, from South America through Africa and the Arabian world to the Far East.

On the map we can see what type of Hungarian railway models were delivered to which country (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

Transport vehicles are important elements of the environment: last year, old steam and diesel locomotives and railway wagons were located in the first round (their interiors can also be seen). The first extension of this year is the section entitled Focus on The Collection, which also features buses, cars, motorcycles and other vehicles important for the Hungarian technical and transport heritage: we can see the 1959 Skoda Octavia live, which defined the cityscape of Budapest in the 60's and in the 70's, but we can also find the Ford T-model, which also had two Hungarian designers, as well as several classic Ikarus buses or the Csepel D-450 truck.

The Unbuilt Budapest is a valuable extension of the huge exhibition space of the Diesel Hall. Those who would like to approach the transport history of a city from an urbanistic or socio-historical perspective can get a lot of interesting information.

Cover photo: Excerpt from the exhibition The Unbuilt Budapest (Photo: pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration