In the 20th century, many crafts that were involved in meeting basic human needs disappeared. One of the most important of these was the work of the water sellers. They were a breath of fresh air on the streets of Buda and Pest for a long time. Although there were wells in the city, their water contained saltpetre and iron, so the watermen went from house to house carrying the water of the Danube in two-wheeled donkey carts.

When there was no epidemic, of course, many people also drank the water from the wells, but they mostly used the softer water of the Danube for washing or cooking. The watermen were mostly Slovaks or Swabians, who walked the streets shouting "Tónavósz", the almost unrecognisable pronunciation of the German Donauwasser - Danube water in Hungarian. At first, the valuable goods were transported on foot, in carts, then on donkeys, and later in horse-drawn carriages.

Watermen in the Buda mountains, early 1900s (Source: Hungaricana – OSZK)

From the 1850s, we know about 20-25 such water sellers, but by the 1870s, their number was close to 100. The price of water was determined by the distance from the river or well, and the floor of the villas or apartment buildings. The 29 January 1865 issue of Vasárnapi Ujság wrote:

"The Danube River waterman starts his hard day's work early in the morning. When the winter frost sets in, his work is very bitter, when he has to cut a hole in the ice and crawl up the steep and slippery bank with his load. He normally has a wife and an assistant, who goes ahead and takes orders, so they can deliver the water portage with little waiting from the vehicle rushing behind them. […] While the two men take the scoops to their destination, the woman guards the cart. The price of the scoops is proportional to the height of the floors or the distance to the Danube. Each floor means one penny difference, and thus the street beyond Váci Road or Országút similarly increases the price of a scoop."

Waterman and his donkey in Zugliget, early 1900s (Photo: Hegyvidék Local History Collection)

The aforementioned 1865 article also highlights how careful the vendors were not to cross each other's territories, which they divided among themselves. It also happened that someone received a Danube wetland as a dowry, which sounds quite strange to today's eyes.

"The Danube River watermen are a good body, whose members fraternally divide the various parts of the city among themselves; one never invades the other's perimeter; it happened the other day that a waterman gave his married daughter a part of Downtown and Terézváros as a dowry; a dowry that even millionaires cannot boast of. There are Danube watermen, who struck it rich; for example, they already work with two horses. Of course, both are blind and not in very good shape. But they are talented just enough to often start 20 full scoops, the burden is constantly diminishing anyway. Besides, we also know someone who pulls the cart alone and carries the scoops upstairs."

Contemporary graphic of a water seller, 1880s

Contemporary graphic of a water seller, 1880s

The wagon of the "Danube waterman" in the second half of the 19th century (Source: Magyarország és a Nagyvilág, 12 February 1871)

Of course, the vendors carried water not only from the Danube, but also from wells and springs with better water. The Hegyvidék (today's 12th District) was, for example, very rich in springs - City Well, King Béla's Well, Disznófő Spring - so here the vendors brought fresh water from the wells in the area, and the cheaper, raw Danube water was mostly only used for cleaning, or watering animals was purchased.

Watermen on Svábhegy in the 1860s (Source: Budapest History Museum)

The Szürke Csacsi ('Gray Donkey') restaurant used to stand on the former Németvölgy Road, which got its name from the fact that the Swabian carriers selling Danube water rested here, and the mountain water carriers bought water from them, filling the scoops hanging on both sides of their donkeys. Fresh drinking water from the springs was delivered to the cottages by people carrying water, and if necessary, this was arranged in advance with the housekeeper or maids.

On 6 May 1911, the magazine Világ recalls these times as follows:

"One hundred years ago or even less, the people of Pest drank the water of the Danube, which was contaminated with typhoid and cholera. From Svábhegy, young children carried the spring water in scoops, and whoever had enough money for it could buy healthy drinking water. The public water pipe was needed so that even the poor could have access to clean water."

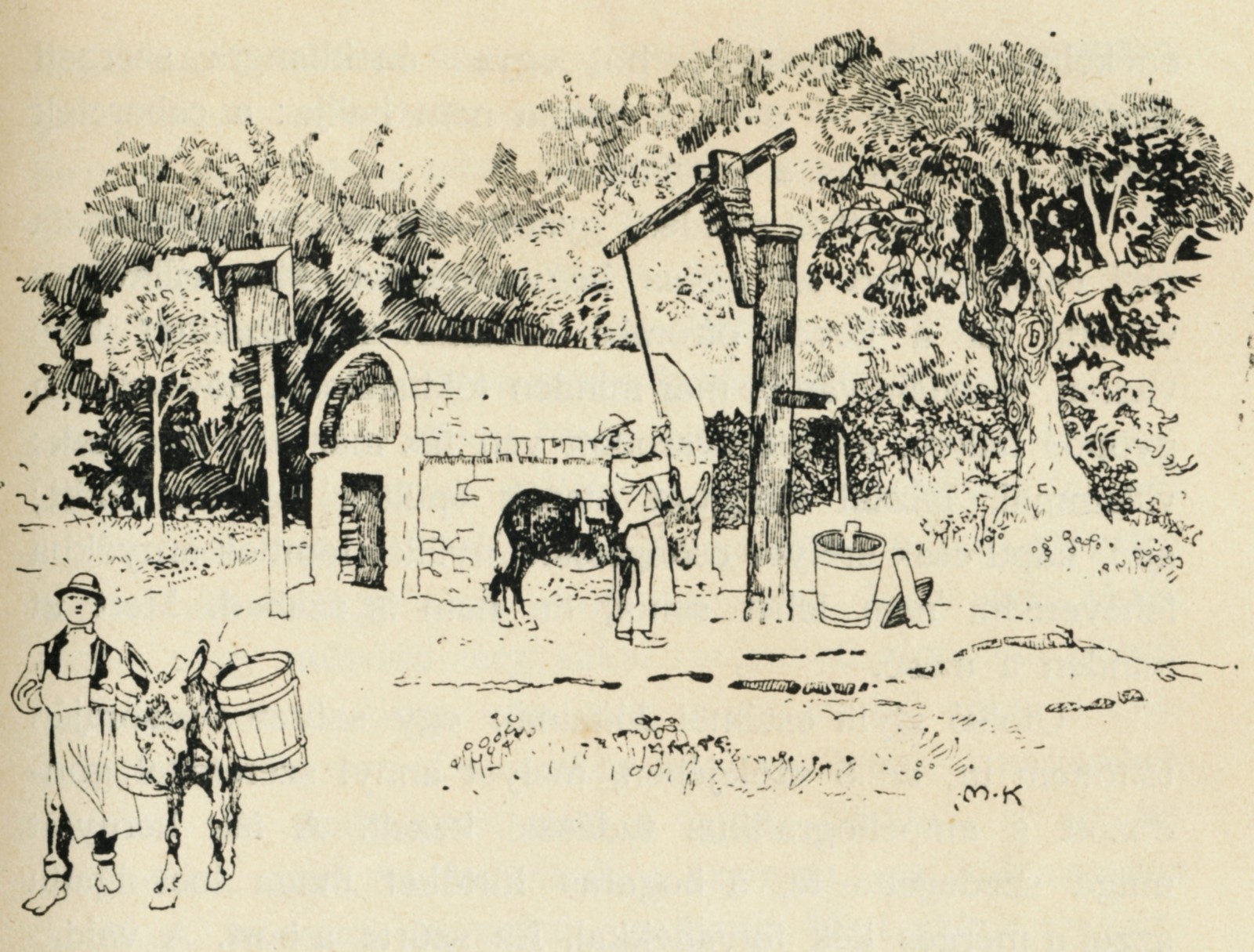

Donkeys at City Well in the middle of the 19th century (Source: Adolf Ágai: Journey from Pest to Budapest, 1843-1907)

However, even the growth of water sellers could not solve the spread of epidemics that were occurring more and more often in the cities, so after the cholera epidemic of 1866, the General Assembly decided after long negotiations on the development of a unified water network, which in the 1860s and 1870s in Pest, then in the 1880s was also established in Buda. Aqueducts greatly increased the process of urbanisation, development and population.

However, even after the aqueduct network was built, fresh spring water was a great treasure, which could only be consumed in moderation. In the more sophisticated households, fresh spring water from the can set aside in the cool basement was always used for special meals, drinks, and tea, even after the pipes were installed. The enormous value of water is also clearly shown by the fact that even in the 1890s, Franz Joseph had water delivered to Buda Castle from Schönbrunn, 250 kilometres away.

Horse cart carrying water in 1905 (Photo: Fortepan/Reference No.: 101878)

With the advent of the aqueduct, springs and water sellers were still used by many people. The Danube water supplied by the vendors and the water from the springs were mostly replaced when typhus and cholera epidemics broke out in the second half of the 19th century. They were primarily caused by the lack of sewerage, and water from drilled wells. Budapesti Hírlap also mentions in its 11 November 1893 issue that Elizabeth did not drink from the wells in Svábhegy due to the cholera epidemic. "The queen drinks the water of Svábhegy, but this year - because there was cholera in the capital - water from the Gödöllő garden was delivered for the majestic woman," can be read in the paper.

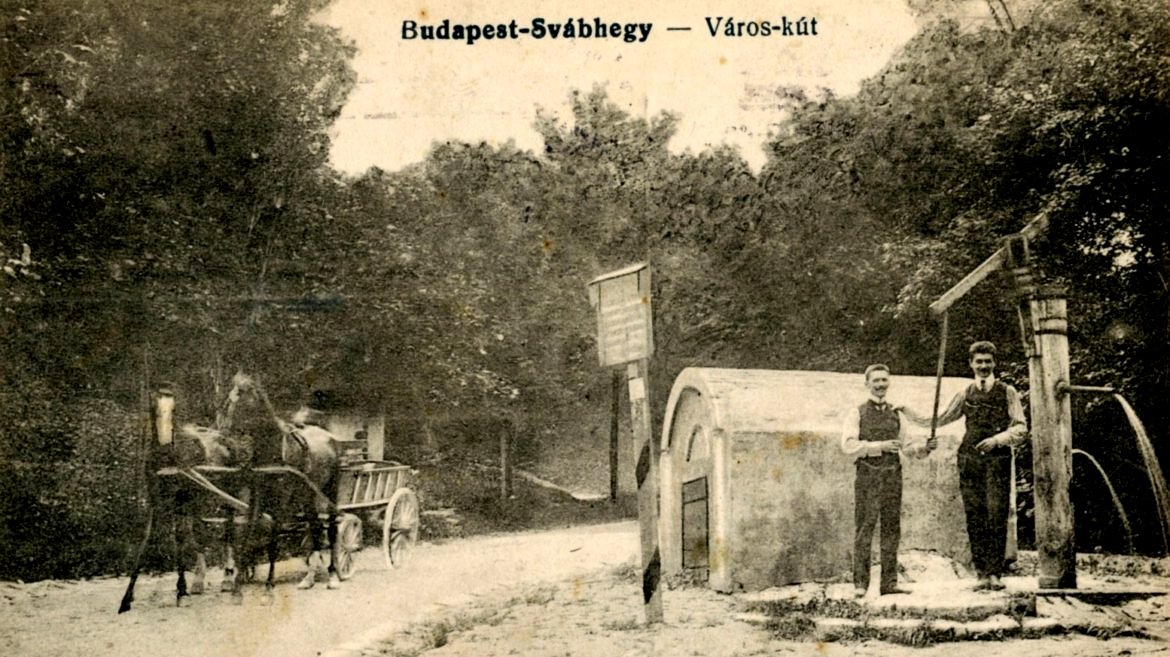

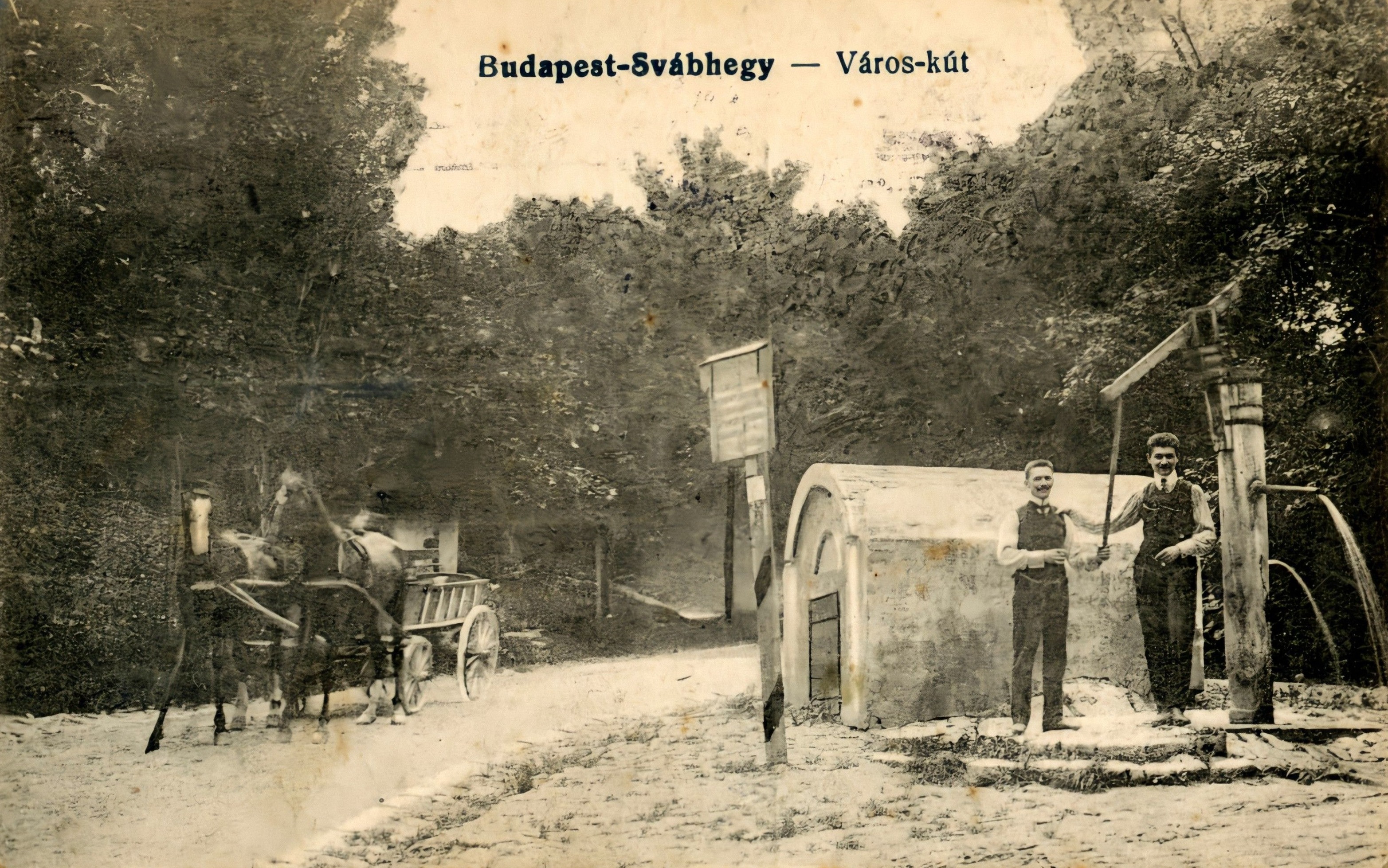

The City Well on Svábhegy in the 1890s (Source: Hegyvidék Local History Collection)

With the spread of aqueducts, public health became better and better, and not only the more fashionable and wealthy, but also ordinary city dwellers had access to normal, healthy drinking water. Water sellers then appeared on the outskirts of the city in the early 1900s, but by the 1910s, this interesting profession had almost completely disappeared from the streets of Buda and Pest. Later, when there was a shortage of water, people weeped for their return many times.

In the 5 August 1917 issue of Magyarország they wrote: "In the mid-1890s, the large waterworks in Káposztásmegyer was finally built. Now we do not need the Danube waterman anymore, the Viennese "Hochquellwasser" is nothing like ours - we said with proud arrogance, and today, no matter how much we turn the faucets, not even a leech comes out of them. [...] we would certainly be happy for them, if the cry "Dóna vész" could be heard all at once on Hatvani Street."

Cover photo: The City Well on a postcard from the 1880s (Source: Hegyvidék Local History Collection)