In the 19th century, most of the mountainous areas of today's Buda were still considered outlying areas, where people went on vacation, and the more affluent also built vacation homes. Among them was József Hild, although he did not accumulate a particularly large fortune, even though he was considered the star architect of the time, as received building permits for more than nine hundred designs.

Portrait of József Hild (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 21 April 1861)

He was born into a family of architects with a long history in 1789, Pest. His father, János Hild, drew up Pest's first urban planning plan, and his uncle, Vince Hild, was associated with, among other things, the Kálvin Square Reformed Church. After graduating from Piarist high school, he continued the tradition and studied as an architect at the Vienna Academy of Arts. He gained his earliest practical experience in the office of his father, János Hild, but also worked in the Viennese office of the French-born Charles Moreau. After his father died in 1811, he took over the management of the business and worked for a short time with Mihály Pollack, but due to the requirements of the guild system, he had to do further studies abroad, which he completed in Italy.

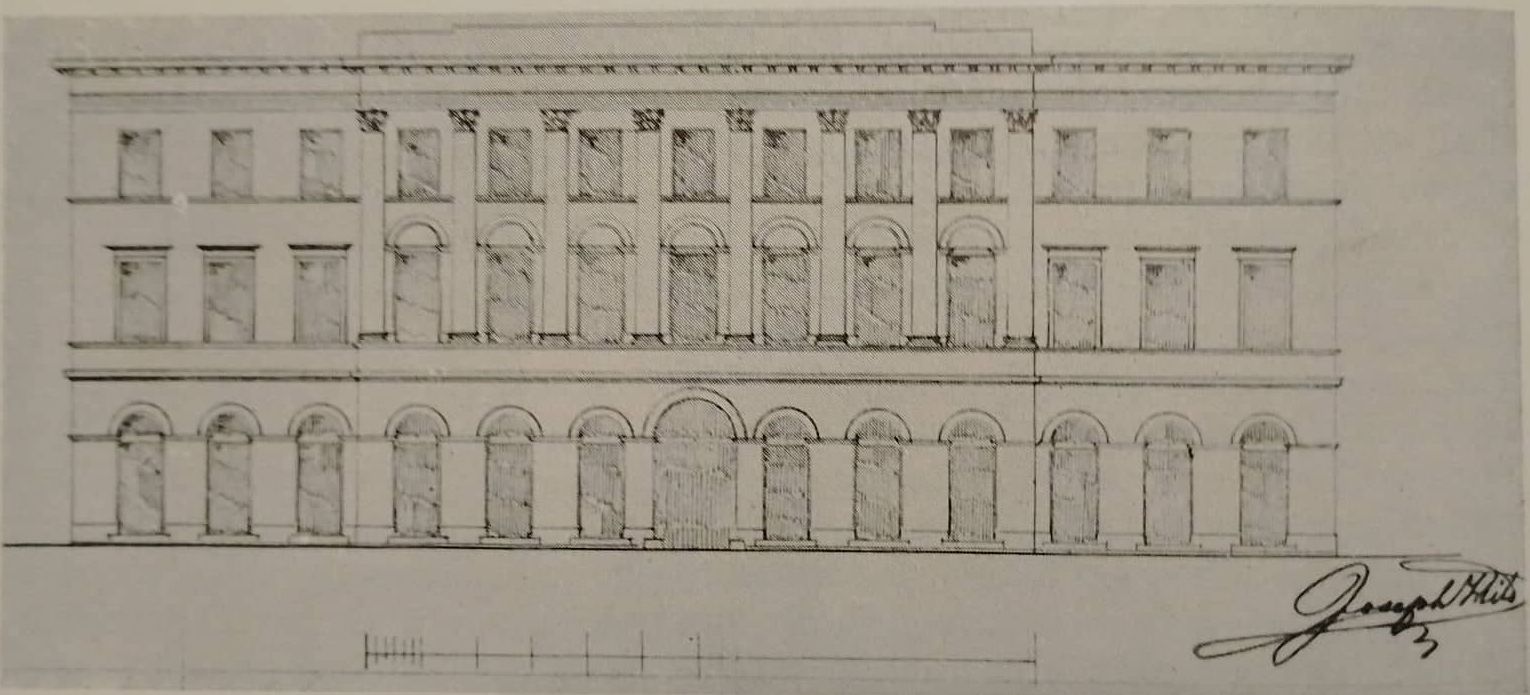

Main facade plan of the Ullmann Palace (Source: Jenő Rados: József Hild's oeuvre, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1958)

At the beginning of the 1820s, he already lived permanently in Pest and got married: in 1822 he married Karolina Ritter. He also received a series of design commissions, and mainly wealthy citizens approached him to draw their palaces in Pest. However, he was forced to rent an apartment: all we know about the first one is that it was in an apartment building on Három Korona Street in Lipótváros. In 1835, he moved to the second floor of the Ullmann Palace on Kirakodó Square (now Széchenyi István Square), in a spacious corner apartment. This already indicates his financial prosperity, which finally led to the fact that in 1844 he was finally able to build his own villa in Buda.

The Hild Villa after the most recent restoration (Source: mma.hu)

The location was Hegyvidék, which became a popular area in the middle of the 19th century. Until then, it was largely covered by forest and agricultural cultivation, mainly vineyards. The first buildings were mainly built by vineyard owners as holiday homes, for recreational purposes, but they soon became popular meeting places for the intellectuals of Pest and Buda. Thus, more and more citizens of the city, including many artists, moved here. They typically built villas, this type of building is larger than a simple residential house but smaller than a castle. Although it contains several rooms, they are generally less representative.

The Tower of the Winds in Athens, on which a special type of column was used (Source: wikipedia.org)

Hild's own villa is located at today's 38-40 Budakeszi Road. It consists of three tracts covered with a gable roof, which are connected by lower wings. The individual blocks form a strong risalit (protrusion) and step forward from the plane of the facade, and the prominent role of the central part of the building is also indicated by its height. The main entrance also opens here, where ten steps lead up, as there is also a cellar under the villa. The road leads to the gate through an open terrace with four columns; these columns are very typical of József Hild's art, as their chapiters follow the column order of the so-called Tower of the Winds. The name comes from an ancient Greek building, the Tower of the Winds in Athens, the columns of which are crowned with chapiters made of sedge leaves, which are special in ancient art.

Miklós Barabás: Palatine Joseph (Source: Hungarian National Gallery)

Hild considered it important to introduce a warmer, more humane version of the otherwise harsh classicism in our country. It would be an exaggeration to call it Hungarian classicism, but it was still important for the master to adapt the style to local conditions. Here, the bourgeoisie was much weaker compared to Western Europe, so the building class was mainly the rural nobility. And they wanted to express the national consciousness that was reawakened in the reform era by making their villas and mansions in shades different from Austrian classicism. In fact, not only Hild but also his great rival, Mihály Pollack, as well as the architects of the time in general, thought this way. A century later, between the two world wars, Jenő Lechner aptly named this Hungarian-style classicism the palatinus style, referring to Palatine Joseph, the statesman who defined the era as a whole (the Latin word palatinus means palatine in Hungarian).

The Hild Villa was rebuilt at the end of the 19th century (Source: mma.hu)

Unfortunately, József Hild could not enjoy the comfort of the villa for long, because of his son's debts, he was forced to sell it to a certain banker named Malvieux. From the point of view of the building, it is fortunate that it later ended up in good hands, because when the Geist Family commissioned József Pucher to expand it in 1889, he made sure that the proportions of the overall picture did not change. The two side wings, originally with columns, were walled up and laterally expanded with the already presented corner blocks. In 1894, a rear tract was also built. The monument and the surrounding garden were last restored in 2016, and are currently used by the Hungarian Academy of Arts.

However, this was not the master's first work in the Hegyvidék: it is known from Gábor Rosch's research that the villa at today's 39B Városmajor Street, built in the 1820s and with a similar four-column terrace, can be attributed to him. This was later expanded by Aladár Árkay with an Art Nouveau block. In 1844, a villa was also built on the neighbouring plot, number 39A, according to his plans, which was later demolished to build another one in its place.

The Csendilla Villa in a watercolour made in 1849 (Source: Old houses in Pest-Buda, Műszaki Kiadó, 1976)

Also built in 1844, the so-called Csendilla Villa, still visible today at 73 Budakeszi Road, got its name from the word written on its tympanum. It is not known exactly what the builder József Bors meant, but Gyula Krúdy attributed the meaning of press house or wine cellar to it. This building is certainly more than a simple farm building, originally there was even a tower in the middle of the roof. Unfortunately, this was destroyed in a fire and was not rebuilt, but otherwise, it was not customary to raise the villas with a tower. Regardless, the building fortunately still stands today and adapts perfectly to the sloping terrain, and offers a harmonious image even in its simple closure. Its gate, which steps forward from the centre of its main facade, is supported by four Tuscan columns, to which stairs lead up, as in previous villas. The side wings here are narrow, with only one window on each. It should be noted that written data does not prove Hild's authorship, it can only be attributed to him based on stylistic criticism.

The Csendilla Villa today (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

One of Hild's most interesting villas was built for hat manufacturers Ferenc Karczag and Benjamin Karczag on the plot at 17 Diána Road in 1845. Like his own house, the columns of the porch were given chapiters following the Tower of the Winds, and above them, there is a triangular tympanum. The gable roofs of the significantly lower side wings are connected to this high central part in the transverse direction. According to Jenő Rados, the unusually dynamic mass system is already a definite sign of the romantic style. In 1894, according to the plans of József Pucher, it was expanded with a rear tract, and in 1913, Kálmán Löllbach created the present-day, glazed form of the courtyard's columned gate (portico).

Villa of Ferenc and Benjamin Karczag on Diána Road (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

In terms of size, Hild's largest work in Buda is the villa at 14C Mátyás Király Road, which was ordered in 1846 by the widow of the wealthy master tailor Vince Libaschinszky. Compared to the previous ones, this one also got a floor, and its central part is not supported by four but six columns. On the ground floor, there is a row of arcades with a semi-circular closure, the pillars of which follow the rhythm of the columns on the upper floor. The openings between the columns are also quite spacious, so the central part becomes unusually wide, which is crowned by a relatively flat tympanum. The main facade bears a strong resemblance to another famous work of the designer, the Lloyd Palace that once stood at the Chain Bridge bridgehead in Pest. The villa gained great fame, which is also indicated by the fact that Mór Jókai described the looks of Kőcserepy's holiday home based on this villa in Svábhegy in his novel Zoltán Kárpáthy. It still fulfils an important function as it is used by the Embassy of the Republic of Korea.

The former Libaschinszky Villa today (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Even the contemporary press is of great help in researching József Hild's work, as the newspapers reported on major constructions. From this it can be said that he designed villas not only for Buda, but also for Pest: the former Szepessy Villa in Városliget Alley and the Bartl and Sandner Villas on Hermina Road advertised the master's talent, but unfortunately, they are no longer visible. This is also true for the majority of Hild's buildings, during the incredible pace of development at the end of the 19th century, many of his creations were demolished to replace them with larger ones. The fate of their designer also came to a sad end, as he died impoverished in 1867. Posterity, however, appreciates his entire work, including the Pest-Buda villas, which are dwarfed by the cathedrals of Esztergom or Eger, which he also designed.

Cover photo: The Hild Villa today (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration