Richárd Füredi was born in Budapest in 1873 and completed his art studies in the capital. At a young age, he was also touched by Art Nouveau and considered it important that the style should also appear in cemetery art. By the beginning of the 20th century, it had penetrated all branches of art and the most diverse areas, but works of art related to the deceased were largely an exception. This is explained by human nature itself since grief is difficult to reconcile with innovations.

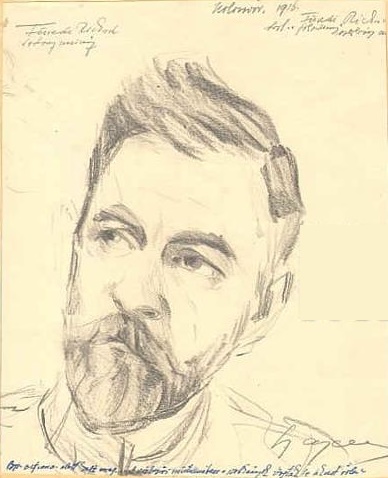

Lajos Szentgyörgyvári Gyenes: Sculptor Richárd Füredi (Source: MTA Research Centre for The Humanities, Institute of Art History)

However, Art Nouveau emerged with such elemental force at the very beginning of the 20th century that it even penetrated cemeteries. One of the largest conquests was in Italy, where individually designed tombstones were created one after the other. It did not leave the Hungarians completely untouched either, because one of the most talented architects of the turn of the century, Béla Lajta (born Leitersdorfer) designed several Art Nouveau monuments and mausoleums - but all of them ended up in the Jewish cemetery in Budapest.

The tombstone of Béla Lajta's mother in the Jewish cemetery on Kozma Street (Source: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

His mother, Dávidné Leitersdorfer born Teréz Ungár, was laid to rest in the Jewish cemetery in Rákoskeresztúr (Kozma Street) in 1903, and he already created a tombstone for her showing the new style. A year later, he designed truly unique tombstones for Sándor Epstein and Malvin Leitersdorfer, also members of his family. One of Lajta's most successful Art Nouveau works is the mausoleum for the Schmidl Family (1904), which combines Hungarian folk art and Jewish religious traditions: on top, a flower with open petals forms a Star of David, ceramic flowers and pomegranates grow from vases on both sides of the entrance, and higher up the fields with wavy outlines are filled with painted plants. The grid of the gate forms a weeping willow, and it is the same turquoise colour as the entire facade covered with ceramics.

The beautiful mausoleum of the Schmidl Family in the Jewish cemetery on Kozma Street (Photo: Máté Millisits/pestbuda.hu)

However, these magical grave monuments, with their boldly new style, stood almost completely alone in Hungarian cemetery art. Richárd Füredi would have liked to see custom-made tombstones spread more widely; the example of Italy floated before his eyes, which is why he believed in success. So he started a business, for which he managed to win the support of the architect Jenő Lechner and sculptor István Tóth. The initiative was given the strange-sounding name Kulatár, the meaning of which is unclear, but it is said to be an ancient word from the time of Grand Prince Árpád.

The arcades of the Castle Garden Bazaar were occupied by sculptors' studios (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.08.090)

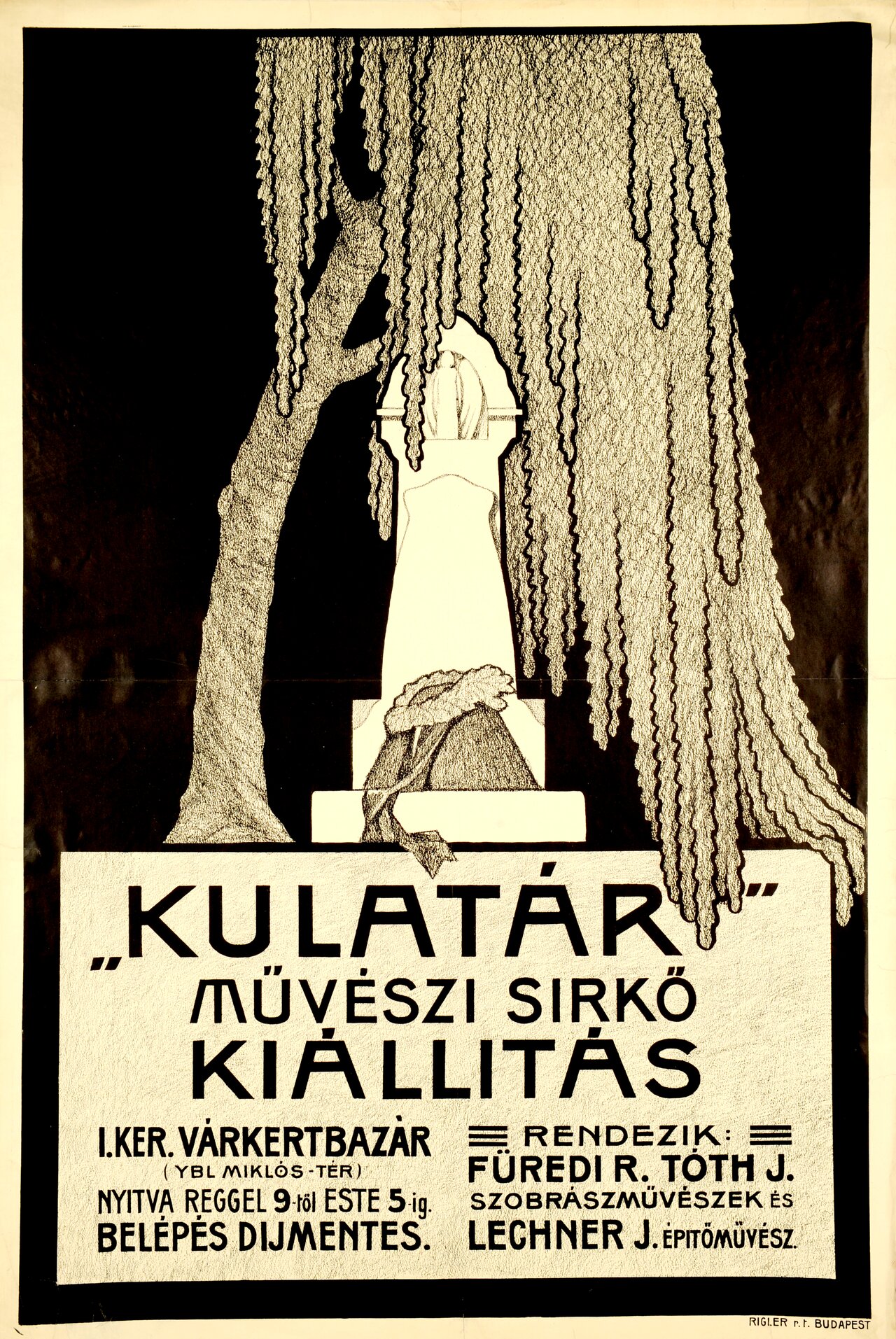

As a first step, a multitude of tombstone models, more than a hundred pieces, were shaped, and then a room in the Castle Garden Bazaar was rented out to organise an exhibition of these miniature monuments. Built in 1875-1883 according to the plans of Miklós Ybl, the arcades of the patinated site were at that time given to sculptors anyway as studios, which was a rather inappropriate use of this Neo-Renaissance jewel box bordering the royal gardens, but it was very useful from the point of view of the exhibition. The opening was held on 21 February 1907, and the exhibition was surrounded by lively interest throughout.

Invitation to the Kulatár Exhibition (Source: National Széchényi Library)

The success was partly because the custom-made tombstones were offered at an affordable price, as this was the only way they could achieve the goal of being widely distributed. On the other hand, the press also reported on the unusual and intriguing event in the country. Dezső Malonyay, an enthusiastic collector of Hungarian folk art memorabilia, wrote the following lines about the exhibition in the columns of Budapesti Hírlap:

"In the small cemeteries of the Hungarian regions, hidden away from the railways and dozens of urban civilizations, they are looking for the characteristic shapes on the headstones of the simple graves carved in the distant hillsides, village forests and the willows of the Hungarian plains, and they have already found many. (…) Their decorations are measured; they look for Hungarianness not only in the motifs of the tulip (...) and they do not consider over-decoration or gallantry to be characteristically Hungarian. (…) He forgets the noble simplicity of the Hungarian character, who always flaunts what he thinks is Hungarian."

Fortunately, two magazines also published photographs of the models, so we can understand Malonyay's review. Three photos were published in Magyar Iparművészet: number 214 shows a semicircular altar on a low plinth, divided by a niche, in the centre of which stands a mystical female figure, and on the edge are male figures in jumping and flying positions.

Model No. 214 published in Magyar Iparművészet (Source: Magyar Iparművészet, Issue 3, 1907)

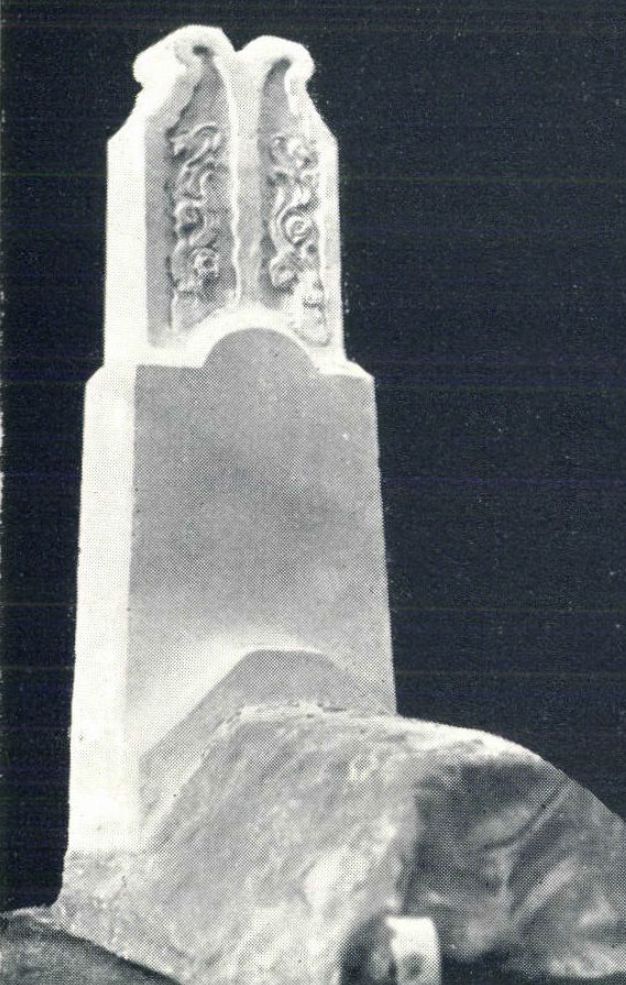

The stele (stone slab) shown in picture No. 215 consists of a square lower part and an upper part decorated with flowers and tendrils. The outline of the latter forms a bud that started blooming. In picture No. 216, a slender stele ending in a peaked arch can be seen, where the edge of the peaked arch is slightly wavy, and a stylised plant ornament was carved into the niche formed in it.

The model No. 215 (Source: Magyar Iparművészet, Issue 3, 1907)

Vasárnapi Ujság published two models: on one, the stele is covered by the drooping branches of a weeping willow, and a female figure looks out from behind them. On the other, a portrait relief in an antique manner was placed in the niche in the upper third of the headstone. The niche is surrounded by very realistic roses, which branch out disorderly from their winding stems. Unfortunately, no authentic pictorial representations of other tombstone sketches have survived, but it is also clear from the ones so far that the mock-ups differ greatly from what is customary in Hungary. In some of them, the Viennese Art Nouveau is stronger (for example, mystical female figures), but with plant ornaments taken from folk art, they gave way to the Hungarian Art Nouveau but did not go into tulip-heroic exaggerations.

The photo published in Vasárnapi Ujság also shows a weeping willow (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 10 March 1907)

The exhibition was such a great success that it was held again a year and a half later, in the fall of 1908, although this time the location was 4 Köztemető Road. Perhaps also thanks to this program, in the following years, Füredi and Lechner were asked to create several uniquely designed tombstones by very wealthy families. In 1916, a tombstone was made for the tobacco merchant Fülöp Adler and his family in the Jewish cemetery on Salgótarjáni Road. It consists of a large stele and a stone sarcophagus lying in front of it. The latter is located on a low platform, to which two steps lead and which is bordered on both sides by a wide stone barrier. At the front end of the railings, a stone cauldron stands on low pillars, reminiscent of the fire-holding vessels of ancient Greek sanctuaries. The stele itself is supported by Greek Doric columns with carved trunks, each topped with an urn.

The gravestone of Fülöp Adler and his family in the Jewish cemetery on Salgótarjáni Road (Source: Építő Ipar, Issue 44, 1916)

In the stone beam supported by the columns, the inscription Fülöp Adler's family can be read in an Art Nouveau font, and below are the names individually. In the upper part of the stele, as a reference to the deceased, there is a bas-relief of an eagle with spread wings (Adler means eagle in Hungarian). The upper closure of the stele resembles the cut of a coffin lid. With the archaic style, Lechner certainly wanted to express eternity; unfortunately, this no longer applies to the tomb itself, it was destroyed during the storms of history.

The business promised long-term success, so they were joined by master stonemason Lajos Balla, who also offered a warehouse to store the pre-made tombstones. During World War I, in 1915 and 1916, an exhibition of artistic grave monuments was organised. Later, Balla - now without the artists - turned the business into a joint-stock company under the name Kulatár Kőipari Reszvénytársaság.

Cover photo: The gate of the Jewish cemetery on Salgótarjáni Road (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration