Industrial development attracted crowds to Budapest already in the second half of the 19th century, and residential houses were built on an assembly line for the people who moved here. The majority of them were in the Neo-Renaissance style, but from the turn of the century, the innovative forms of Art Nouveau also prevailed. No matter how fast new flats were built, they could not keep up with the growth of the population, so at the turn of the century, the capital was already characterised by a housing shortage.

Later, this became an even more pressing problem: according to statistical data, Budapest's population grew by 95,000 people between 1910 and 1927, and approximately 7-10,000 flats were missing from their healthy distribution. The situation was further worsened by World War I when construction was halted due to the lack of men who had been drafted into the army, but the peace treaty did not bring a solution to this either, because at that time, due to the extreme inflation, no one dared to undertake such a large-scale investment as the construction of a residential house.

Councillor Endre Liber, director of the small flat construction program (Source: National Heritage Institute)

Since private capital could not be persuaded to start construction, the local government had to start it. At the end of 1925, the General Assembly of Budapest with its 1282/1925 decree decided to implement a larger-scale small flat construction program and they provided financing for it from the budget of 1926. The implementation was managed by councillor Endre Liber, who entrusted the design to the capital's best architects because they had the guarantee that they would do an adequate job both artistically and structurally. When issuing construction works, he also strove to get as many craftsmen as possible employed, and for a master to work in only one place, thus reducing the excruciating unemployment.

The capital gave the architects a free hand in choosing the style, although most of them still used the Neo-Baroque style that best suited the conservative arrangement. So did Dezső Hültl at the residential house under 33–43 Simor (today Vajda Péter) Street, which is expressed by the robust ledges and the basket arched windows of the ground floor. Also, its mass system is quite dynamic.

The Neo-Baroque residential house at 33–43 Vajda Péter Street, with the tower of the former Lutheran church in the foreground (Photo: Balázs Both /pestbuda.hu)

Three different architects designed three residential houses on the section of Váci Road between Csavargyár Street and Mura Street (today 170 Váci Road): Jenő Rupp, Artúr Sebestyén and Kálmán Lux. For the sake of a harmonious appearance, they strove for a uniform facade design, the window shafts of all three buildings are separated by large pillars. Most of the openings are simple bricks, but the designers still placed ornaments in the window aprons and hood mouldings. The wavy gable wall and mansard roof of the middle residential house were very beautiful Neo-Baroque forms, but unfortunately, today only a very stripped-down form of it can be seen.

Plan of the group of residential houses at 170 Váci Road (Source: Magyar Építőművészet, Issue 3–4 1927)

Not far from here, at the intersection of Váci Road and Gyöngyösi Street (2 Gyöngyösi Street), the long-standing office of Ármin Hegedüs and Henrik Böhm designed a residential house. At the turn of the century, they became known for their Art Nouveau buildings, but they also created these three residential houses in the Neo-Baroque style. Still, there were exceptions, as the building with expressive features by Béla Rerrich was directly next to them, and the classicising residential house of András Létay was placed under number 6.

The residential house on the corner of Gyöngyösi Street and Váci Road in 1927 (Source: Magyar Építőművészet, Issue 3-4 1927)

István Medgyaszay also built the three residential houses on Budaörsi Road (4-18 Budaörsi Road) in his highly individual style, containing oriental features. The reinforced concrete barriers of the balconies are broken by familiar motifs from folk art (e.g. tulips). The facade at the height of the second floor was originally decorated with Ferenc Márton's sgraffitos depicting folk scenes, but today, unfortunately, it can only be seen on one of the buildings. Loránd Friedrich also designed two residential houses on Budaörsi Road.

István Medgyaszay's characteristic style is also reflected in the Budaörsi Road residential house (Source: Magyar Építőművészet, Issue 3–4 1927)

Lajos Friedrich, who designed the residential building at the intersection of Mester and Dandár Streets (37–39 Mester Street), was not related to him. He certainly owed his commission to the fact that he also worked as the chief engineer of the capital. The characteristic features of the building were the semi-circular balconies protected by iron railings, which were scattered on the facade on several different levels. Most belonged to just one door, but the ones facing the corner were larger, spanning three window shafts.

Residential house at 37-39 Mester Street nowadays (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Opposite it, on the other side of Dandár Street, Jenő Lechner designed a seven-story residential house (33–35 Mester Street). Along with Medgyaszay, he was the one who most expressed his own vision of the ideal architectural style: he mixed different trends in a very individual way. Gothic architecture can be discovered in the arched openings of the corner loggias (terraces behind the wall plane), and antique architecture in the half-column-balcony design around the entrances. The latter has an exact prototype: the columns of Emperor Nerva's Roman Forum.

Several styles are mixed on the residential house at 33-35 Mester Street (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Under the influence of his uncle Ödön Lechner, Jenő also tried to give his buildings a Hungarian feel, which can be seen in this residential house, for example, in the lilies decorating the heads of the half-columns, as well as in the ancient Hungarian male and female heads of the guardian stones supporting the balconies. The balconies and the railing of the staircase are decorated with a lattice, shaped like a Hungarian knot [vitézkötés] (stylised tulips and plant tendrils that also appear on the uniforms of the hussars). Lechner was a deeply religious Catholic, so he attached a blue ceramic house blessing on the corner block: between the year 1926, the initials of the names of the Three Kings were also written.

Hungarian details of the residential house designed by Jenő Lechner: pillar heads, guard stones and balcony railings (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

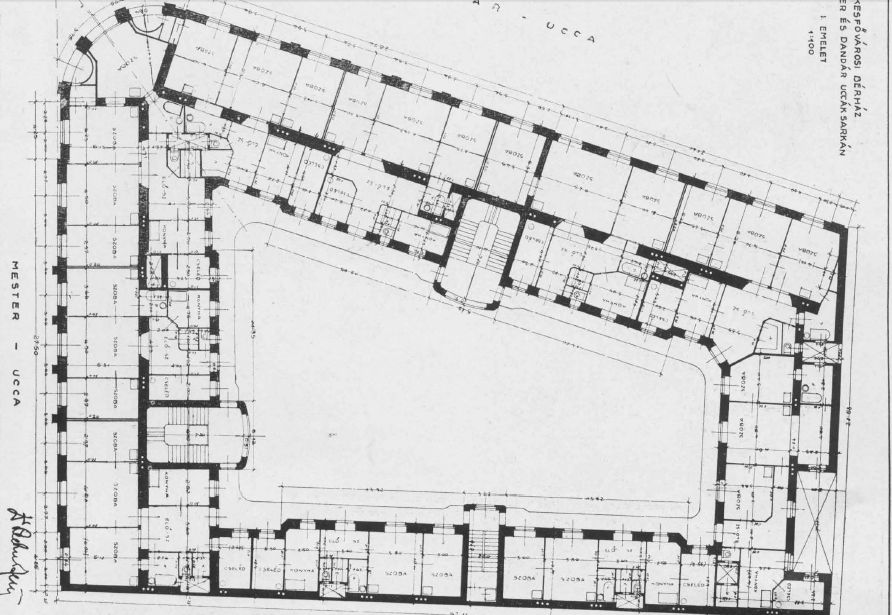

Using the example of Jenő Lechner's work, it can be felt that these residential houses between the two world wars differed not only in the personality of the builder and their style from their counterparts from the time of dualism but also in their internal structure. While previously, in order to use the plot as efficiently as possible, wide building wings were erected on all sides of it, and only a narrow inner courtyard remained free, while here they paid more attention to healthier living conditions so Lechner designed two tracts to be narrower.

First-floor plan of the residential house at 33-35 Mester Street (Source: Magyar Építőművészet, Issue 3-4 1927)

Thanks to the frugal spacing, they were able to create seven four-room, thirty-eight three-room, and fifteen two-room flats in it. This was the most comfortable of the residential houses built in the small flat construction program, as indicated by the predominance of three-room flats, and there was also space for garages on the ground floor. The flats had modern equipment, including servants' rooms and bathrooms, however, unnecessary luxury was avoided: the individual floors became lower than usual, and window structures that opened together were used.

The flats only extended from the first to the fifth floor, because the ground-floor rooms were given over to shops and workshops, and the basements housed warehouses and laundries. Within each flat, the larger rooms faced the street front, while the smaller ones and the restrooms faced the inner courtyard. There were staircases in three of the four tracts, only the shortest one lacks it, but of course, it was possible to approach it from the other wings as well. Transportation between floors is also provided by elevator.

Stairs run around the elevator at 33–35 Mester Street (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

A total of 887 flats with 1,335 rooms were handed over as part of the small flat construction program. Overall, it can be said that the action was successful, as thanks to this, the housing shortage in the capital decreased somewhat in the second half of the 1920s, and thanks to the talented architects, the cityscape was enriched with rather aesthetic facades.

Cover photo: Residential house at 33-35 Mester Street nowadays (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration