Ábrahám Ganz was at the peak of his success in 1867. The factory of the esteemed citizen of the city of Buda flourished, that year they celebrated the production of the 100,000th bark-cast railway wheel. Ganz has come a long way since the small foundry, employing just seven people, began operating in early 1845.

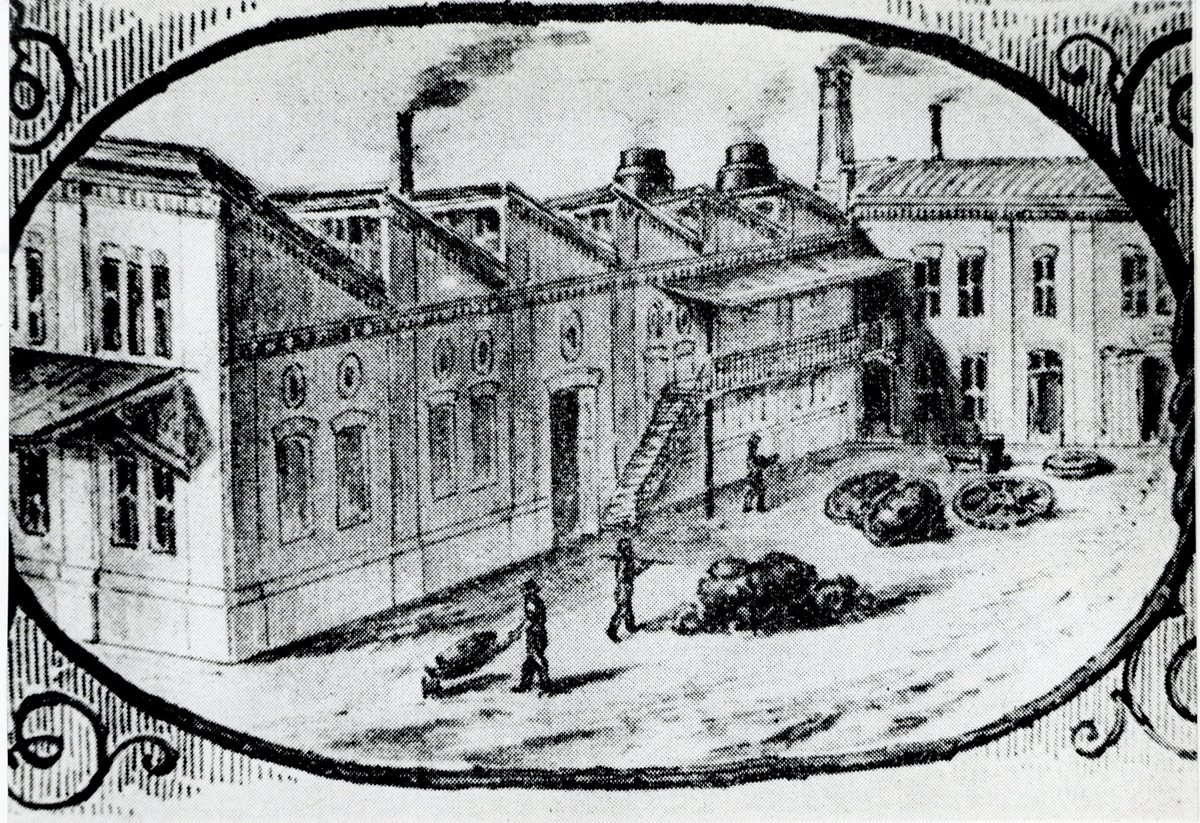

The Ganz Foundry in 1867, the commemorative plaque at the casting of the 100,000th wheel (Source: Hungarian Museum of Transport, Ábrahám Ganz Foundry Collection)

At that time, the Ganz Factory supplied railway wheels and gear parts to 59 railway companies in Europe. The great invention that brought success was the cast wheel, which was not originally Ganz's patent, but he developed it further. The essence of the cast wheel is that the part of the mould, where it was in contact with the flange of the future wheel, was coated with an antimony material, which caused the edge of the wheel to cool down faster, and due to the components incorporated here, from the materials applied to the coquille, the outer few millimetres of the casting became stronger and harder than inside the wheel, a kind of crust was created. The railway wheel was thus somewhat flexible and hard at the same time. At the Paris World Fair of 1867, the factory exhibited a wheel that had been used for 16 years, ran millions of kilometres, and still looked like new. Of course, it won great acclaim.

Ábrahám Ganz's house on the Danube bank was designed by Miklós Ybl. The building was destroyed in World War II (Photo: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.068)

The casting of the hundred thousandth wheel was a big deal, it was also celebrated separately, as reported by Vasárnapi Ujság on 1 December 1867:

"In the factory of the well-known manufacturer (Ábrahám Ganz) in Buda, the hundred thousandth wheel was completed these days. On this occasion, Mr Ganz organised a celebration for his workers, factory staff and close friends in the Tüköry Hall, at which around 800 guests were present. The workers glorified the factory industry, diligence, perseverance and honesty, these attributes, which provided the Ganz Factory with such a well-deserved reputation."

Ábrahám Ganz, with his much younger wife and two adopted daughters - they had no children of their own - lived at that time in a three-storey palace designed by Miklós Ybl and built in 1866, on the banks of the Danube in Pest, on the corner of today's Széchenyi Street. At that time, he was only 54 years old, and his wife was only 35.

However, storm clouds were gathering over Ganz. He was tormented by constant headaches already in Switzerland in 1866. When he visited home - since he was born in Switzerland, he cultivated the connection with his native land throughout his life - he did not come directly home but took care of himself in a seaside spa in Ostend. His family was affected by a hereditary mental illness, Ábrahám Ganz's two sisters also died of it, and it is believed that the symptoms of this disease were discovered by the already exhausted man, stressed by loads of work. In addition, in mid-December 1867, there was a minor interruption in the plant due to the weather, which hindered punctual deliveries.

A cast iron wheel from 1865 from the Ábrahám Ganz Foundry Collection (Source: Hungarian Museum of Transport, Ábrahám Ganz Foundry Collection)

The Ganz Family sat at the table for Sunday lunch on 15 December 1867. Ábrahám Ganz suddenly stood up, looked at his adopted daughter who was lying sick, then went up to the second floor of his palace and threw himself down from the height. He died instantly. His funeral took place two days later, according to the 4 January 1868 issue of Magyarország and Nagyvilág:

"If nothing else, his great funeral would have been a great testimony to the loss that his death caused to the Hungarian industry and the interests of the city. At the head of the funeral procession were the workers of the famous iron foundry, of which the deceased boss was a real father. The six-wheeled hearse was preceded by a city guard of honour, followed by representatives of the city. Countless torches were lit next to the coffin, and it was accompanied by funeral flags, a large crowd and an endless line of carriages."

Not long after, Ganz's will was opened. According to this, he left the factory and its plots in Buda to his five surviving Swiss brothers, and the Pest palace and other properties to his wife. They were not the only ones living in the palace, the Ganz Family only used the 13-room apartment on the first floor of the large building and the basement - the warehouse for the factory's finished products - the other apartments were rented out, so Ganz took care of the widow's financial security in this way. Several of his relatives inherited cash and other plots of land. The following advertisement appeared in the papers, which Pestbuda now quotes from the 11 February 1868 issue of Budapesti Közlöny:

"— Attention.*) In the seventh point of the will of the late Mr Ábrahám Ganz, he bequeathed 200 HUF to all those to whom he or his spouse was godfather or godmother. Those who request this are hereby requested to present their baptismal certificate, on which the priest must also note that the claimant was alive until 1 December 1867, to prove their claim."

This was necessary because Ábrahám Ganz was the godfather of many factory workers' children since the factory was founded, and he left 200 HUF to each of his godchildren. He had a total of 64 godchildren, and the executors of the will were waiting for their application.

Portrait of Ábraham Ganz (Photo: Wikipedia)

The fact that the Ganz Factory did not disappear in the following years is a minor miracle, because what would the five brothers still living in Switzerland have started with an iron factory in Buda? They could not manage it from there, because their two brothers, Jakab and Konrád, who worked alongside Ábrahám in Buda, had already passed away. However, the heirs made a decision that proved epoch-making. The factory was not sold or broken up but was turned into a joint-stock company, and a three-person board of directors was first appointed to manage it. The technical director of this council and, from 1875, the sole general manager of Ganz and Co. Iron Foundry and Machine Factory PLC became the Bavarian-born András Mechwart, who, by the end of the century, had made a huge industrial company far exceeding world standards with some of its products from a relatively small factory in Buda, employing 370 people.

Cover photo: Mausoleum of Ábrahám Ganz (Photo: Péter Gyula Horváth/hirado.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration