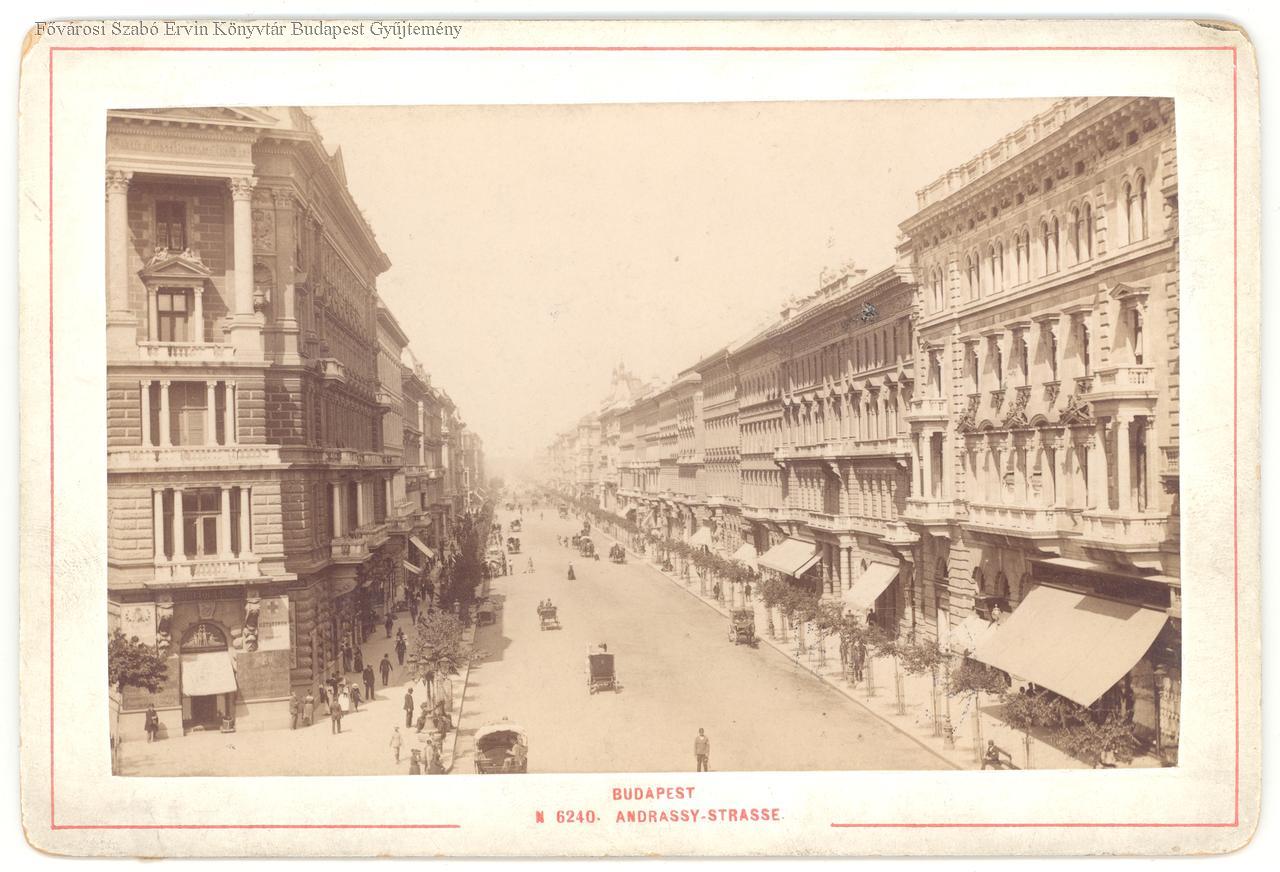

By 1869, Budapest, with a population of nearly three hundred thousand, had jumped from 42nd place (listed at the beginning of the 19th century) to 16th place on the list of the most populous European cities. However, the main street of Terézváros, Király Street, which was crowded and carried public health risks, could not cope with the increased traffic demands. In 1870 a decision was made to build Sugár Road, today’s Andrássy Avenue, the width of which resolved to “allow light and fresh air to flow through it” as the official report of the Budapest Public Works Council in 1877 states.

Andrássy Avenue in 1890 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The construction of Andrássy Avenue, which was completed by 1876, was not even finished when the Pest Public Road Rail Tracks Company applied for a permit to build a horse-drawn railway along its length. This was followed by several other initiatives, from the development of the omnibus network to the construction of the surface tram network, but all were rejected. In the end, the real push to build the continent’s first underground railway was the upcoming celebrations of the national millennium and the National Millennium Exhibition, to which the organizers were expecting plenty of visitors.

A significant argument favouring the “kisföldalatti” (also known as the Millenium Underground Railway or the M1 metro) was that as an underground solution, it did not disturb the view of the elegant palaces on Andrássy Avenue.

The construction of the “kisföldalatti” in 1895 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 28418)

A tender was announced for the design of the entrance halls, but none of the seven applications received approval, so the decision-makers decided to make new plans.

In her book, The Millennium Underground Railway, Ágnes Medveczki states that the entryways' location was a hot topic, especially the ones at Oktogon and Deák Square caused the designers a headache. The entrances at Oktogon were on the side of the square closer to City Park on the original plan, but later they were moved to the downtown side for safety reasons, despite arguments that the entrance halls would negatively affect the elegant surroundings of Andrássy Avenue.

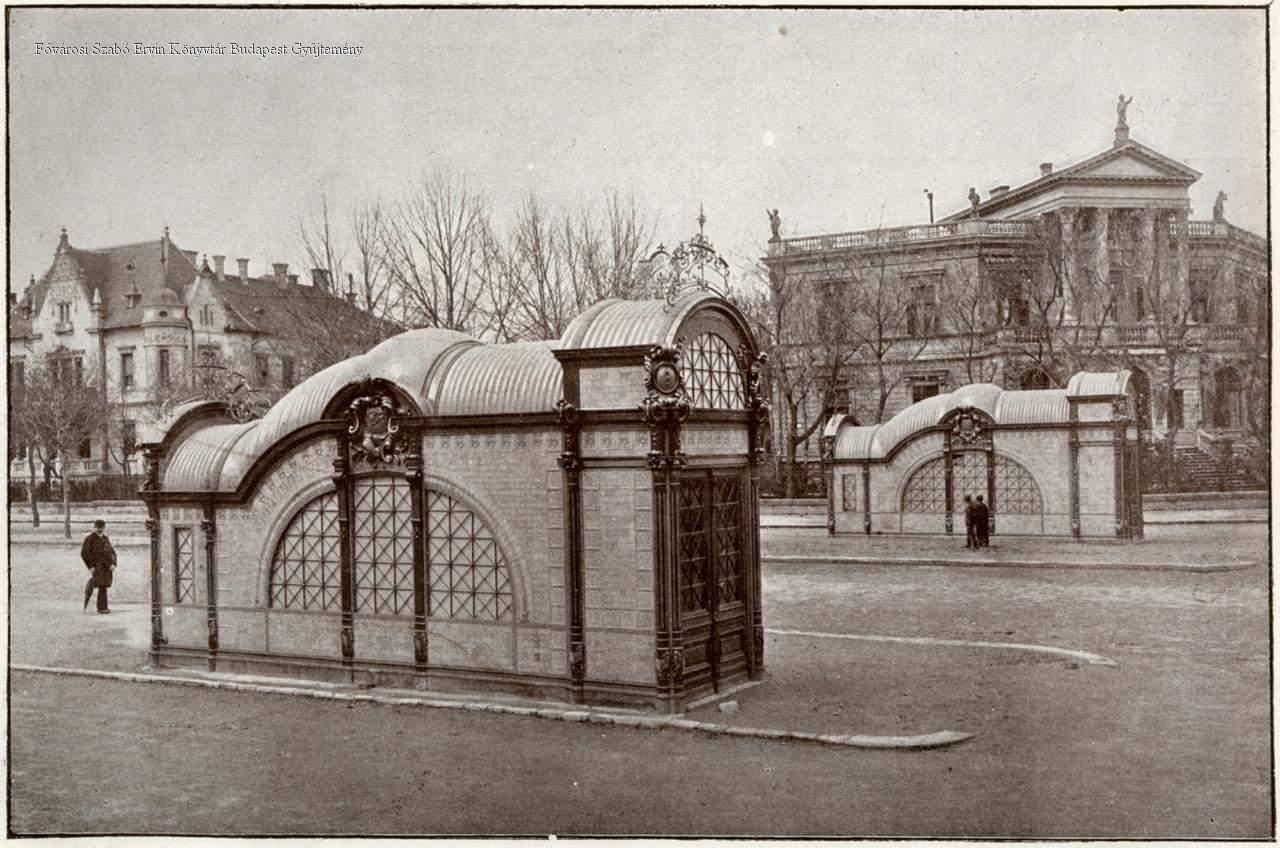

Between 1896 and 1924, the Deák Ferenc Square hall decorated one of the capital's busiest transport centres. It was later demolished because of its ornate implementation. Contemporary picture by György Klösz (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

A similar discussion took place around the design of the Deák Square entryway. In the end, the idea of the Public Works Council was accepted, so a significantly larger pavilion was erected here, covering both entrances. The 102-square-metre, domed hall was eleven and a half metres high in the centre, while the two sides above the entryways were over five and a half metres high.

The large, tin-domed pavilion on Deák Square was designed by György Brüggemann. Also, based on his ideas, ten identical, much more modestly designed, 18-square-meter, tin-covered pavilions decorated with light majolica tiles were built at Váczi Boulevard (now Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Road), Vörösmarty Street, Bajza Street and Aréna Road (now Heroes’ Square station; formerly Dózsa György Road was called Aréna Road).

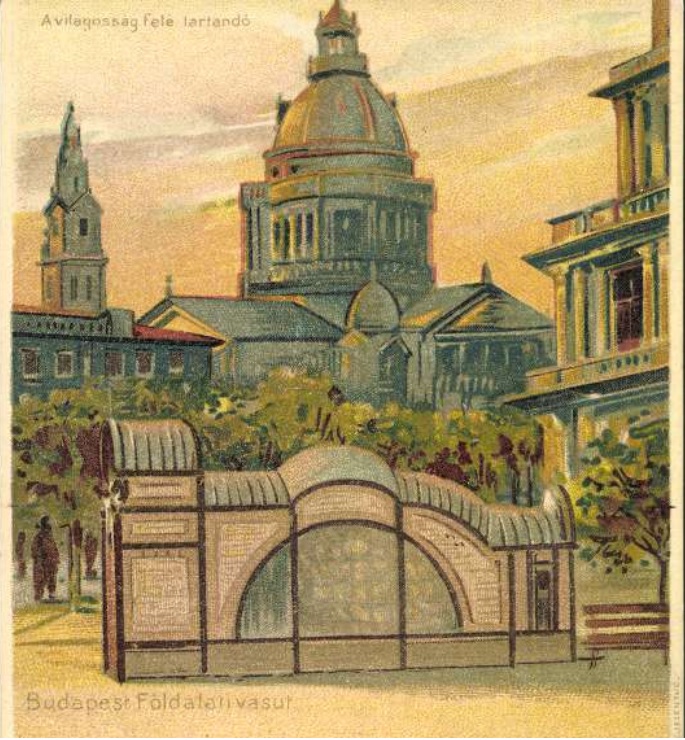

The entrance at the old Váczi Boulevard station (now Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Road) with St. Stephen’s Basilica in the background (Source: Contemporary postcard)

The entrance halls of the former Aréna Road station (now Heroes’ Square) in the photo of György Klösz in 1896 (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The most ornate halls, which were located at the Gizella Square terminus (now Vörösmarty Square) and Oktogon, were designed by Albert Schickedanz (a prominent representative of historicism), in collaboration with Fülöp Ferenc Herczog. Schickedanz, who made grandiose plans for the Millennium Monument, the Kunsthalle, and the Museum of Fine Arts, was also happy to work on smaller projects such as the halls of the underground railway.

The 24-square-metre pavilions, designed by Schickedanz, were decorated with coloured pyrogranite bricks fit between iron frames. Their roofs were also covered with pyrogranite. The decorative elements were made by the Zsolnay Factory, as were the brown and white tiles covering the platforms.

The two entrance halls of the underground railway terminus (formerly Gizella Square, now Vörösmarty Square) in 1896. The pavilions were designed by Albert Schickedanz, in collaboration with Fülöp Ferenc Herczog, to whom the plans of the Millennium Monument, the Kunsthalle and the Museum of Fine Arts can be attributed. Photographed by György Klösz (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Gizella Square (today Vörösmarty Square), one of the terminals of the underground, between 1890–1910, photographed by György Klösz. In the lower right corner of the picture is a 24-square-metre, small entryway decorated with Zsolnay elements, designed by Albert Schickedanz and Fülöp Ferenc Herczog (Photo: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.08.144)

Oktogon at the beginning of the 20th century. On the left, the station of the Millennium Underground Railway. This pavilion was also designed by Albert Schickedanz and Fülöp Ferenc Herczog (Source: Wikipedia)

The construction of the entrance halls was allowed following the customs of the age, taking the cityscape into account. This proved to be so important that a pavilion was not even built for the Opera House's entryway (designed by Miklós Ybl) and the Drechsler Palace opposite of it (designed by Ödön Lechner) as they would have obscured the representative buildings.

In front of the Drechsler Palace and the Opera House, only stone railings were made, not entrance halls, as they would have obscured the representative buildings (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

During the permitting procedures, the now seemingly astonishing idea of the Public Works Council (a body set up to plan and supervise the capital’s public works) was floated that the underground entrances should not be on public premises but simply placed in nearby houses. From this, one can easily recognise the thinking of the era: they insisted on covered entrances.

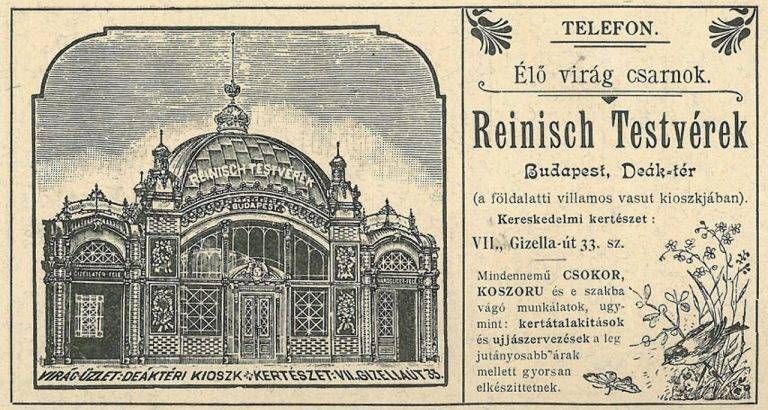

The idea was probably born due to practicality. The goal would certainly have been to make the entrance halls beautiful and useful, for example, to protect entryways and the travelling public from the vicissitudes of the weather. And the pavilion in Deák Square not only protected people from rain and wind: its central part was sublet to shops. The Reinisch brothers’ flower shop, among others, was located here.

Advertisement of the Reinisch brothers’ flower shop in the November 1898 issue of Magyar Iparművészet (Hungarian Applied Arts Journal)

Advertisement of the Reinisch brothers’ flower shop in the November 1898 issue of Magyar Iparművészet (Hungarian Applied Arts Journal)

The Reinisch brothers’ flower shop at the Deák Square kiosk around 1896, photographed by Károly Divald (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

However, changes in the cityscape and modernisation are often relentlessly take their toll. The pavilions of Schickedanz at Gizella Square were demolished in 1911–1912 due to the construction of the Vörösmarty Monument. Brüggemann’s entryways, including those on Deák Square, were demolished in 1924 because the “majolica crypts” did not meet the changing demands of the age.

The small buildings were judged to be too ornate and were also cited as obstructions to surface traffic. In Deák Square, the area in front of the Lutheran church stood empty for a long time after the demolition, a simple flight of stairs led to the underground, and then much later, during the construction of metro line 2, today’s glass cube rose.

Statue of Lenin on Deák Square during the Hungarian Soviet Republic, 1 May 1919. The pavilion designed by Brüggemann was covered with red cloth (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

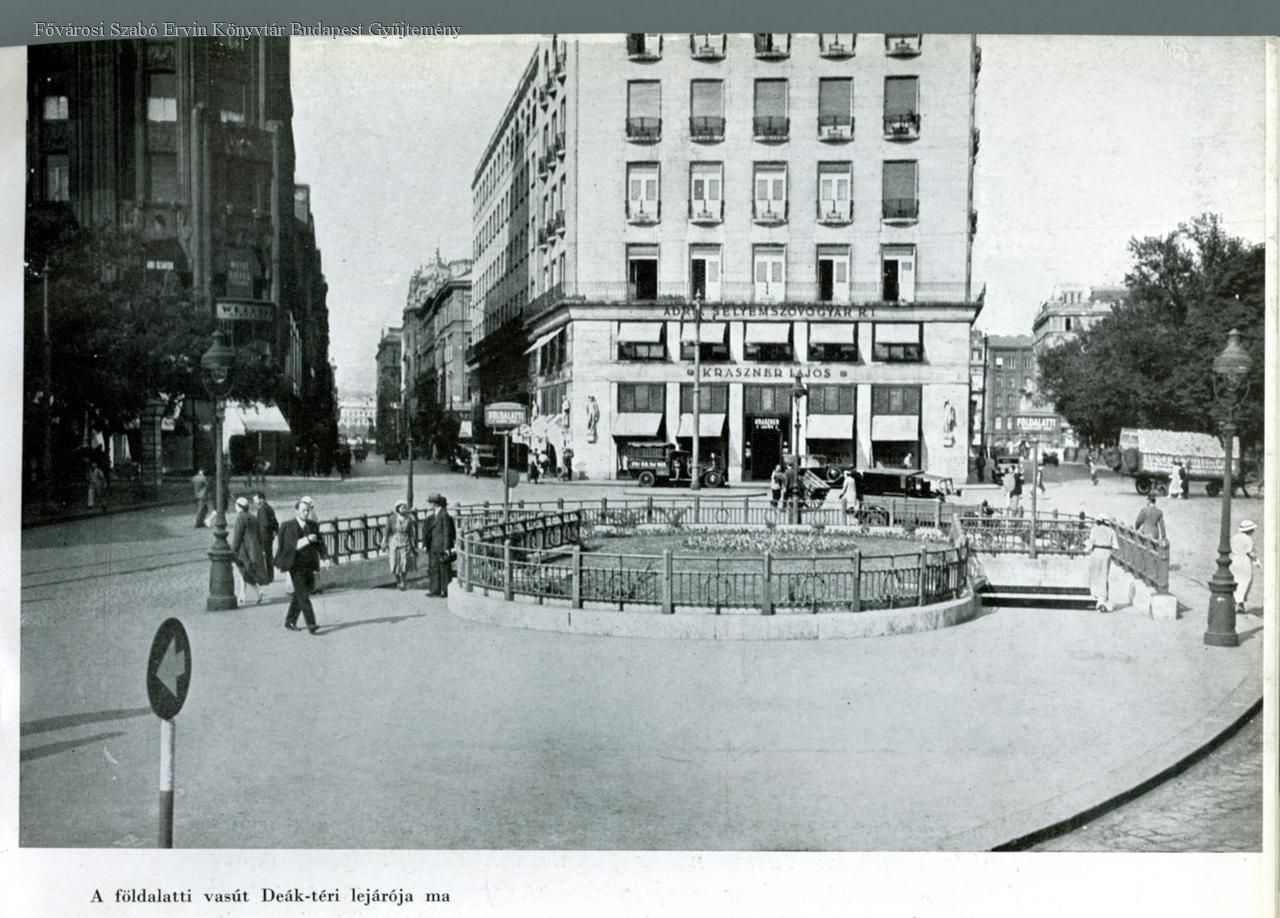

The new entry of the underground railway after the demolition of the pavilion, the picture was taken by an unknown artist in 1934. In the background, the lower part of today’s Ritz-Carlton Hotel building also shows the name Adria Selyemszövőgyár Rt. and the shop of Lajos Krasznai (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Today’s Deák Square. In the foreground, the monument of the Lutheran pastor Gábor Sztehlo, unveiled in 2009, with the Lutheran church in the background (Photo: Balázs Both / pestbuda.hu)

Today’s Deák Square. In the foreground, the monument of the Lutheran pastor Gábor Sztehlo, unveiled in 2009, with the Lutheran church in the background (Photo: Balázs Both / pestbuda.hu)

The hall of the Deák Square entrance of the underground today (Photos: Gyöngyi Kővári/pestbuda.hu)

The hall of the Deák Square entrance of the underground today (Photos: Gyöngyi Kővári/pestbuda.hu)

Entryways to the underground on Vörösmarty Square today (Photo: Gyöngyi Kővári/pestbuda.hu)

The entrance hall that once stood on Deák Square can now only be seen in the Underground Railway Museum, in the form of a mock-up. The picture of the small building was also presented at BKV’s recent virtual exhibition so that those interested could learn about the history of transport in the capital during the pandemic.

The former ornate pavilion on Deák Square, which welcomed the travellers of “kisföldalatti”, can now only be seen as a mock-up in the Underground Railway Museum.

In this respect, the Karlsplatz station of the famous Austrian architect Otto Wagner, which opened in 1899, was much more fortunate. The Viennese pavilion bears many similarities to Brüggemann’s pavilion on Deák Square, built a few years earlier.

The pavilion, showing features similar to Brüggemann’s Deák Square entrance hall, was built in 1899 and was designed by Otto Wagner as the entry of the Karlsplatz station in Vienna (Source: Wikipedia)

Although the demolition of the Karlsplatz entrance hall was also discussed during the major renovations in 1981, there was such public outrage at the news that the mayors finally decided to keep the station building, so the Karlsplatz domed hall still adorns Vienna’s city centre. Sadly, the people of Budapest can only admire the magnificent domed pavilions that once adorned the city by looking at old photographs.

Cover photo: The large, 102-square-metre pavilion, designed by György Brüggemann, on Deák Square in front of the Lutheran church (Photo by Mór Erdélyi from 1900)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration