Rats were (or are) a significant problem in every city. The extermination of rats has been going on in Budapest in an organized and continuous manner for only 50 years. Before then, the fight against rodents was campaign-based, as happened in 1931.

The campaign was prepared very carefully 90 years ago. The Minister of Welfare issued the extermination decree in 1929, and a tender was issued to carry out the task. A total of 147 applicants submitted offers. These included frivolous competitors who wanted to lower the number of animals with a stick, but people reading incantations also applied.

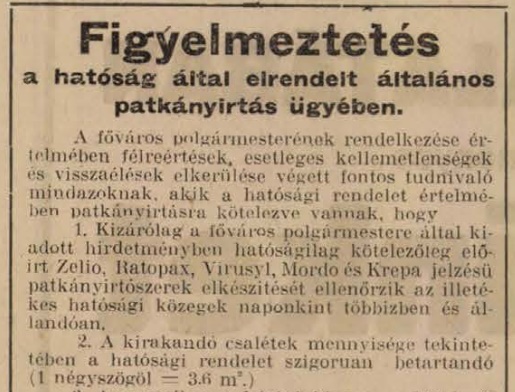

Announcement of the rat extermination in the 10 May 1931 issue of the Pesti Hírlap

There were 54 serious applicants left in the second round, and then the capital selected seven of them because the sewer network was divided into 7 districts. Eventually, only five applicants remained standing. The 15 May 1931 issue of the Honi Ipar reported on the preparations:

“Four of the five chemicals: Ratopax (Trés), Mordo (Puritas), Krepa (Vajda and Róna), Virusyl (Ibis) contain sea onions, and the fifth: Zelio (Medichemia) contains talinum as the main ingredient.

The five companies were required to process their liquid rodenticides into solid material. That is what happened, and then Trés stated they would deliver for 5.40 pennies. Eventually, everyone involved finally agreed on the same price.”

The capital decided that the poison created by Medichemia could only be used in sewers, uninhabited areas, barns, landfills, and factories because the material had a higher poison content.

On the streets of Budapest in 1931 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 187593)

By 18 May 1931, the other four companies had to produce 15,000 kilograms of rat poison each. The chemical contained sea onions and other toxins that caused heart and kidney cramps for the animals. It was considered an advantage that the poisons would lead to the animals dying in its den, not in an open area. The poison was placed either as a porridge or soaked in bread.

The lengthy preparations were criticised on several points in the quoted article, which found it problematic that homeowners could use other chemicals and could not even determine exactly how much poison was needed.

The Outer Ring Road at the intersection with Rákóczi Road in 1929 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 19188)

Before the “campaign,” general cleaning was ordered throughout the city, and by the end of February 1931, rubbish to fill 8,300 transport had been removed. The rat extermination began on 23 May, and the Friss Újság wrote the next day that the offensive had been launched:

“Fatal Whitsun dawns on the rat flocks in Budapest. Maybe the day of red Whitsun does not dawn on them because the planned offensive will start against them at six o'clock on Saturday night. The mayor signed the death sentence of all rodents of the "underworld" of Pest with Decree No. 66,080. The siege against the rats will last for a week and will end at 6 a.m. next Friday. However, the rat exterminating council has been working hard for weeks and the projected shadow of the general offensive, if possible, is already terrifying the residents of the canals.”

The one-week campaign was supported by 2,000 people, Budapest was divided into 30 districts, and the chemical engineers supervised the rat extermination masters, who in turn directed the auxiliary workers. The latter were recruited from discharged soldiers and received one week of training.

The "campaign" was described in the previously quoted article:

"The engineer stays on the street; the masters go into the house with the crew and place the poison together with the homeowner's agent."

The preliminary plan was to exterminate 80 per cent of the rat population in Budapest and then collect millions of corpses to burn.

The campaign misfired in the villa district, where mainly pets were the victims (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 134970)

However, not everything went according to plan. The papers reported at the end of May that in the garden suburbs and villa districts, it was not the rats but dogs, cats and birds that were primary victims. After the operation, in July 1931, it was estimated that one million rats were killed by the extermination, which, however, according to contemporary reports, was only a small part of the Budapest population. The work may have been hampered by the fact that a large-scale rat control operation was launched in the settlements around the city with a few-week delay in late May and early June.

Váci Street in 1938 (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The results of rat extermination were difficult to summarize, and data was received from only 20,000 of the 27,000 houses. Thousands of homeowners were prosecuted for unplaced or not properly placed poisons.

Cover photo: Csalogány Street in 1931 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 115651)

Budapest, PestBuda, pestbuda.hu, Csaba Domonkos, Histories

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration