The model for the design of the Avenue came from Paris. During the reign of Napoleon III, Paris was significantly remodeled by Baron Georges Eugène Haussmann: he opened up crowded medieval neighborhoods with elegant, wide, airy boulevards. True, one of the purposes of the construction of these avenues was, in fact, to make it more difficult for the inhabitants of Paris to build barricades and to facilitate the movement of the army within the city.

However, the urban developers of the elegant boulevards created a “fashion”, just as the political elite who came to power by the Austro-Hungarian compromise in 1867 were thinking about how to create a European Budapest rivalling Vienna from Buda and Pest. There were a good number of ideas and many came up with suggestions.

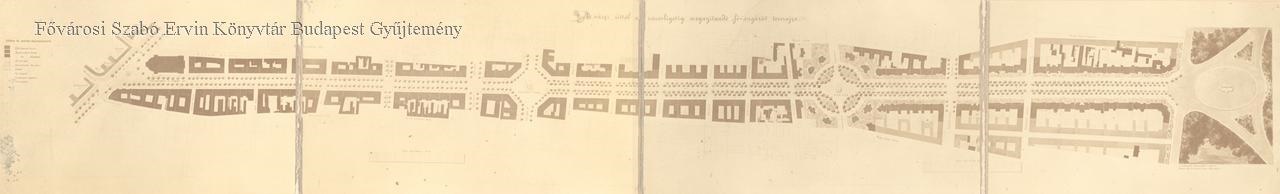

Plan of the Avenue at the Public Works Council. The first section is closed to Oktogon, then it relaxes a bit to the Körönd, where the road is bordered by a service road on both sides. The villa district is located outside the Körönd (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

On Pestbuda, too, the name of a Belgian gentleman, Joseph Toussaint could often be read, who presented his idea of urban development to Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy at a time when he was busy developing the city. This Belgian gentleman broke with the prevailing idea, which was then Ferenc Reitter's canal plan, and proposed elegant boulevards.

Andrássy, who lived in Paris during the year of his exile, knew the French boulevards and embraced the idea: Budapest does not need a canal, but an elegant ring road and boulevard.

The ring road and the boulevard were therefore included in the urban development goals by 1869. A separate law was passed on the Avenue, the Act LX of 1870, which allocated 3,335,909 HUF from the 24 million loan taken out for construction under Act X of 1870, and transferred a further 4,863,812 HUF as a loan to the Budapest Public Works Council, which became responsible for the construction of the road.

Visual design of the Avenue, submitted to the Public Works Council (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The Avenue was actually not a significant transport route in the 19th century, at least not in the sense as the Outer Ring road or Kerepesi (Rákóczi Road), it served primarily representative purposes, so famous architects such as Miklós Ybl and István Linzbauer were commissioned to design the buildings here.

At that time, it was still planned that much of the buildings lining the road would be completed by 1877. The areas along the route of the planned road were expropriated by the Public Works Council, ie bought and converted into plots to fit along the route of the Avenue, and then sold to contractors who would have built uniform-style buildings there. However, the financial crisis of 1873 balked the plans, with many entrepreneurs returning the land instead.

After the crisis, construction continued, but at that time the investors were no longer financial and construction contractors, but the upper middle class and the nobility built here, building villas, smaller palaces on the outside of the Avenue, which was already intended as a villa district.

At the completion of Villa Weninger at 126 Andrássy Avenue, in 1876. In the background you can still see the old ground floor buildings (Fortepan / Budapest Archives. Reference no.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.063)

However, paving the road was completed by 1876. But not with stones, because the Avenue was covered with wooden cubes. On October 10, 1873, the Hon wrote about the choice of the wooden cube cladding:

“About the pavement of the boulevard the decision was made for it to be produced using granite and trachyte paving. Meanwhile, Norris John made an offer to produce this pavement, to build it with wooden cubes. This offer from the contractor Norris, after careful discussion by the technical committee, and given that a similar pavement, also established by Norris two years before at the Buda chain bridge head and tunnel, is still in good condition, (…) finally considering that the pavement in question is not only is it more affordable than granite and trachyte paving, but unlike granite paving, its production and maintenance for twenty years would only cost as much as the construction of the granite paving would take in the first year, - it has been decided that the pavement of the Avenue should be made from wooden cubes."

The pavement was completed by the end of August 1876, and was officially handed over on Monday, 21 August, but car traffic had already begun a day earlier, on 20 August, which then fell to Sunday.

But there were significant problems with the wooden cube cladding within a few years, as John Norris’s system was fundamentally flawed, his unsaturated (i.e., improperly pretreated) wood deteriorated very quickly. Not just on the Avenue, but on the other streets paved by him. In many places the pavement had to be replaced, which was made more difficult by the fact that the entrepreneur, who in principle undertook a guarantee for his work, disappeared from Hungary in 1879, accumulating a large debt.

In the case of the Avenue, the repairs could be covered from the money until the mid-1880s, which was not paid to Norris as collateral. At that time, it was customary for entrepreneurs to receive a certain percentage of the agreed amount only after the expiry of the guarantee, which could be up to a decade.

However, palaces and public buildings continued to be built on the Avenue, so the Opera House opened in 1884, the pretty villas were completed, and in 1896 - because an above-ground tram was not allowed for cityscape protection reasons - the undeground train started under the elegant boulevard called Andrássy Avenue since 1885.

Cover photo: The Avenue facing the Városliget,in the foreground the intersection of Nagymező Street. The recording was made around 1878 (Photo: Fortepan / Budapest Archives. HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.107)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration