The original name of today's Andrássy Avenue was simply Sugárút, as it led radially out of Pest's inner city in the direction of City Park. It took the name of Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy only in 1885. The Parliament decided on its creation in Article 60 of 1870, and the construction was managed by the Budapest Public Works Council, founded in 1870. Based on their proposal, the construction companies received full tax relief for fifteen years and partial tax relief for the next fifteen years. This really acted as an incentive, and private capital began to build residential houses.

Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy, the mastermind behind Sugárút (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

Work first started at Nyolcszögtér - that is, today's Oktogon - in 1872. According to the plans of Antal Szkalnitzky and Henrik Koch, the Sugárúti Építő Vállalat built four Neo-Renaissance residential houses in three years, i.e., by 1875. The style is characterised by the pursuit of harmony, which is reflected in the symmetry of the facades: the five window axes of the slightly forward central protrusion (central risalit) are joined by three-axis sections on each side.

The Nyolcszög Square residential houses were among the first to be built on Sugárút, the picture was taken in 1880 (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.06.020)

The buildings are three-story high, but the central risalit is also elevated by the so-called attic, which extends above the main cornice, and at the same time emphasises its importance. The Neo-Renaissance also comes into effect in the varied elements of the facade: the windows on the first floor are circular (segmental arch), those on the second are closed by a straight hood moulding, and on the top floor the stems of the semi-circular windows are decorated with so-called armouring. This procedure was most often used on the corners of buildings, which also strengthened the building.

Neo-Renaissance apartment buildings in Oktogon nowadays (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

They did not have a direct neighbour, but not far from them, the plot at today's 32-44 was also taken over by machines and workers. The area between Nagy Mező and Gyár Streets (today's Nagymező and Jókai Streets) was previously occupied by Frigyes Hutter's one-story houses, which were demolished by the Public Works Council after the purchase so that Sugárúti Építő Vállalat could build residential houses here as well. A huge building complex consisting of seven buildings was imagined here, the plans of which were drawn up by Emil Unger. In the contemporary press, it was referred to only as Hét házhely [Seven building plots]. The building permit was obtained in July 1872.

The intersection of Andrássy Avenue and Nagymező Street around 1880 (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.107)

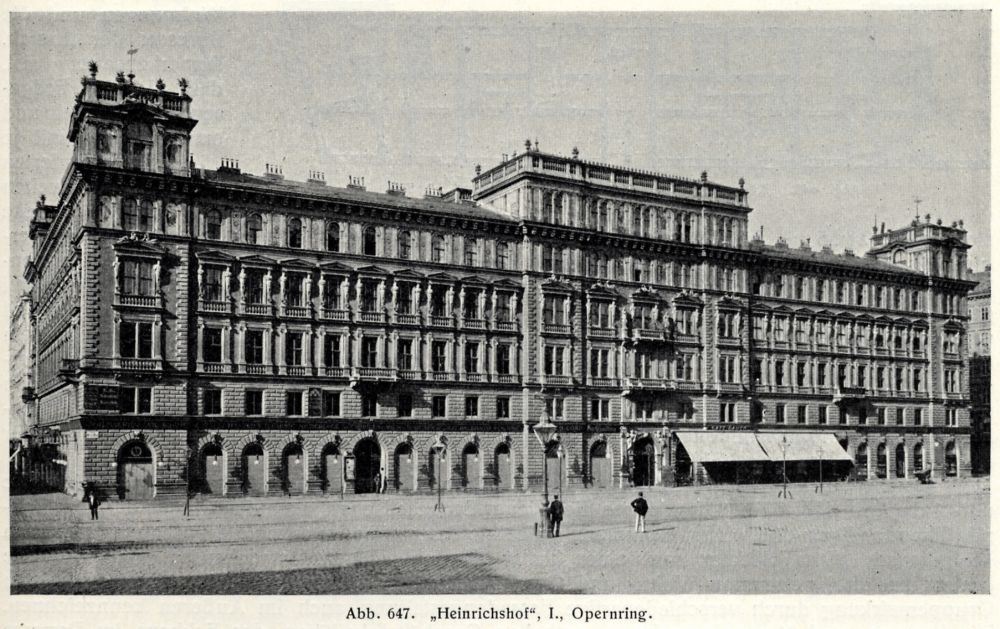

The harmony of the Neo-Renaissance was also reflected in the layout of the buildings: four-story blocks were placed on two corners and in the middle, which were joined by two three-story houses each, thus giving a symmetrical overall picture. The facades are characterised by a horizontal emphasis, as the individual levels are separated by sculptural string-courses. On the higher buildings, the forward placement of the edges (risalites) and the pillars and columns covering several levels in the middle offset the horizontality, thus creating a harmonious facade in itself. The overall picture, especially the design of the risalites, shows that the designer was influenced by one of Theophil Hansen's Viennese residential houses, the Heinrichshof on the Opernring.

The Heinrichshof in Vienna may have been the prototype of the building complex (Source: de.wikipedia.org)

On Andrássy Avenue, the entrances of the lower houses in pairs are located on the edges closer to each other, and due to their identical framing and the balcony extending above them, they look like a single large gate (portico). The whole block is basically characterised by windows with straight closures, which are complemented by strong hood mouldings on the second floor. At the top, however, there are windows with segmental arches and semi-circular arches. The Neo-Renaissance was very fond of balustrades, which appear here in the parapets of the balconies and the aprons of the windows.

The blocks facing Jókai Street nowadays (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The layout of these early apartment buildings was even more humane than the buildings with hanging corridors that were widespread later, which disregarded the private sphere, and the floor areas of the apartments were much larger. It should be noted that the outer houses included an inner courtyard with a circular corridor, but in the rear tract only two apartments were created per level and both had several rooms. Up to three apartments were added to the upper floors as well. The staircases were also quite spacious, with beautiful wrought-iron railings on their semicircular walls.

The sophisticated details of the facade (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The construction was hampered by an unexpected tragedy already in the first year: in 1873, the designer Emil Unger died at the age of only thirty-four. The work was inherited by his former master, Miklós Ybl, and his signature is also on the remaining plans of the building. However, the architectural giant did not modify his student's drawings, so they were realised based on his ideas. Most of them were completed by 1874, but they continued to work on the residential house on the corner of Nagymező Street for several years. The intervening financial crash was also responsible for the delay: in May 1873, share prices on the Vienna Stock Exchange began to fall, which caused an economic crisis. The situation was further aggravated by the cholera epidemic.

The Hétház building complex in 1955 (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU_BFL_XV_19_c_11)

Due to the economic difficulties, Sugárút, which was just starting to take shape, was in danger: many entrepreneurs terminated their contract with the Budapest Public Works Council. Fortunately, the upper middle class and many aristocratic families considered it important to appear with their own palace on this representative road of Budapest, so they built on the vacant lots. The investment can therefore be clearly described as a success story, which even the economic crisis could not break.

Cover photo: The building complex in 1955 (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU_BFL_XV_19_c_11)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration